In his comics he’s delved into such weighty topics as death, family, marriage, parenting, success, failure, the creative process, and the pleasures of drinking wine. What other major, essential topics has Eddie Campbell left to cover?

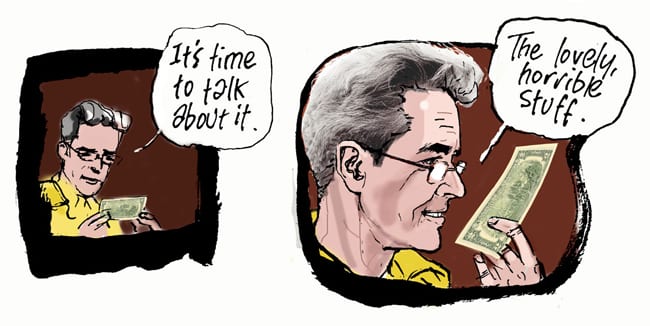

Well, money, for one. And in The Lovely, Horrible Stuff, Campbell’s latest graphic novel, he proceeds to do exactly that, bringing his wry, anecdotal skills to the topic of finance, both high and low. In the book, Campbell looks at small-potato Ponzi schemes, examines how the global recession affected his own projects, talks about bubblegum cards and his father-in-law and spends a good bit of time on the island of Yap, where they like their coins really, really big.

Of course it’s not really a book about money. As Campbell readily admitted in the back-and-forth email interview we did last month, Stuff is more an examination of what we treasure and how those treasures can make life difficult for ourselves as well as others.

It’s always a pleasure to talk to Campbell about his work and the comic industry in general. And even though distances prevented us from actually conversing in real time, I think you’ll find his voice comes out loud and clear all the same.

MAUTNER: The world of the cartoonist is not one embedded with financial security. Did your own experiences as a struggling artist, as well of that of your colleagues, prompt this book? How long have you wanted to do a book about money?

MAUTNER: The world of the cartoonist is not one embedded with financial security. Did your own experiences as a struggling artist, as well of that of your colleagues, prompt this book? How long have you wanted to do a book about money?

CAMPBELL: The book isn't really any more about money than a trip is about a plane. I know I say it is on the title page, but that's just part of the storyteller's art. Everybody wants to know something about money. I did a slide show/talk recently, which was free entrance, which was based around my new material. I started by saying, “Anybody who thought this was going to be an investment seminar better leave before I start.”

Everybody laughed and nobody got up. But a couple of minutes after I started, a couple of elderly people sitting right at the front got up to their feet and shuffled out. Any ideas about how to consolidate their declining assets and how to parcel out their estate they'll have to get from elsewhere.

The thing about money is that it is the site of our bitterest encounters. Money is a story. How it was got and how it was lost, the rise and fall of the empire. It's quite revealing that the grand soap operas of the 1980s were about money. Dynasty. Dallas.

But getting down to the personal, I didn't want to make out that an artist has any more money problems than any other person, so that's not what it's about either. But in the wake of the global financial crisis we've all been thinking a bit more about money lately than we usually do.

MAUTNER: I didn't mean to imply that as an artist you've got more money problems that the average Joe. It's more that I was wondering if, in choosing a career that typically isn't regarded as a path to financial stability, you feel like you've been afforded a perspective about money that the average person doesn't necessarily have.

MAUTNER: I didn't mean to imply that as an artist you've got more money problems that the average Joe. It's more that I was wondering if, in choosing a career that typically isn't regarded as a path to financial stability, you feel like you've been afforded a perspective about money that the average person doesn't necessarily have.

CAMPBELL: Most people take a lot of things for granted, like what a thing is worth and how much they should get paid for an hour's work etc., but for a few other people nothing arrives without a set of negotiations. Like agreeing on how much is to be paid then, when the time comes, having to phone up to make it happen, then having to shepherd the money through international exchange channels. Nothing is ever worth the same amount twice. I don't take anything for granted. There was a time when I got two Australian dollars for one American. Now I get less than one. And I make all my income from foreign countries, so multiply the problem by Euros and pounds. So yes, I guess I see money differently from Joe Average. Explaining it to my wife is where the difficulty resides.

MAUTNER: What made you decide to travel to Yap? Did you go there with any preconceptions or expectations and if so, how were they met or challenged?

MAUTNER: What made you decide to travel to Yap? Did you go there with any preconceptions or expectations and if so, how were they met or challenged?

CAMPBELL: My investigation into some odd corners of the story of money led there. These people, cut off from the advances of modern civilization, appear to have arrived at some of the abstractions of modern finance using these bloody great stone discs for money. It raises some interesting questions. I was interested in the notion that if money was independently invented on some obscure tropical island, would the story still end in bitter recrimination? That's the way it ends everywhere else, insofar as we ever hear about the subject we hear about it when it's going wrong.

MAUTNER: You mentioned "bitter recrimination" which is certainly evident in the book, especially in the sad story regarding you and your father-in-law. Right around the time I started reading Stuff, the MegaMillions lottery here in the U.S. was at an astronomical sum (something like $600-plus million), and the newspapers were full of suggestions on what to do if you won the money, which mainly boiled down to "Don't tell anyone. Don't share it with anyone. And don't spend it, at least not right away," which I thought echoed nicely with some of the themes in your comic. Are there any benefits then to money? Does it always, in your opinion, lead to trouble eventually and expose our worse selves?

CAMPBELL: The truth is that we only ever hear about it when it goes wrong. There are people all over the world quietly putting their money away in retirement funds. They retire and die and never disturb the surface of the water. Elsewhere, Atlantis sinks beneath the sea, or the Kraken wakes.

CAMPBELL: The truth is that we only ever hear about it when it goes wrong. There are people all over the world quietly putting their money away in retirement funds. They retire and die and never disturb the surface of the water. Elsewhere, Atlantis sinks beneath the sea, or the Kraken wakes.

MAUTNER: Apart from learning about and visiting Yap, what other sorts of research did you do? Did you feel the need to delve into any heady economic theory for the book?

CAMPBELL: I did do a bit of reading about basic monetary theory, but that was so that I wouldn't say anything patently stupid. My pal Daren White, who wrote The Playwright, and who in fact makes an appearance in Lovely Horrible, is a chartered accountant by profession. He did me the favor of giving the book a good scrutiny to make sure my theory was logical. I do actually cover the basic structure of the history of money using bubblegum cards (made up ones), so there is some real economics in the book.

MAUTNER: You don't directly address it, but if you had to put your finger on it, what do you think it is about human nature that we feel the need to create this incredibly complicated financial system with seemingly goofy rules and concepts that cause at least as much trouble as they do benefits?

CAMPBELL: Everything goes from grand to paltry. Given long enough the human being can destroy anything, even the planet he lives on. Destroying a system of equitable exchange is child's play.

MAUTNER: You've incorporated collage and photography in your work before (most notably in Fate of the Artist) but never I think this extensively. What prompted this particular style and is it something particular to this book or do you see yourself continuing to use it in future autobiographical works?

CAMPBELL: I'm always moving forward and this is just the next step. I had wanted to colour The Playwright in Photoshop but I couldn't make it work so that it still felt like my hand at work. So I did that in watercolor and scanned it in. But once I had done that I was starting to figure out the angles and if you look closely at The Playwright you'll notice a lot of computer effects starting to creep into it. I was eager to start a new book using all the techniques I was learning.

MAUTNER: How much was done on computer and how much was pen and paper? Can you guide me through the process of putting the book together?

MAUTNER: How much was done on computer and how much was pen and paper? Can you guide me through the process of putting the book together?

CAMPBELL: I lettered it and drew it in ink. However, a lot of the ink drawing got removed later. I found that I was just using it as a guide most of the time. Once I had the color on it I found most of the ink drawing was surplus. And as for the photos, I went to Yap with a lot of sketching equipment, but there was so much to record in too short a time and too many questions to ask, so I photographed it, and having done that, it made sense to just put the photos in the panels. I had already been dropping photo backgrounds in a lot of panels in the first half of the book. It's a way of moving along quickly. On the other hand, some things that look like photos have got up to a dozen components all bundled together to make the picture I need. It's all about picture making, and finding the most efficient ways of doing it. But I think I've cobbled it all together into my own particular cartoon language.

MAUTNER: As someone who famously smashed a computer mouse in one of his comics, what's your relationship with technology like these days?

CAMPBELL: We get along fine. But if you hang around long enough you'll still hear me ranting like a madman when I accidentally delete a day's work.

MAUTNER: Continuing on the technology theme, what is your impression of digital comics? How do you feel about people reading your work exclusively online or via e-readers? Do you feel the paper version is superior or do you not have a preference?

MAUTNER: Continuing on the technology theme, what is your impression of digital comics? How do you feel about people reading your work exclusively online or via e-readers? Do you feel the paper version is superior or do you not have a preference?

CAMPBELL: The only comics I'm reading at the moment are the old romance comics from Jim Vadeboncoeur's collection as they get scanned and put up at the Digital Comics Museum. I thoroughly enjoy reading them like that because I can zoom in whenever I want to. Who needs paper? I think it's good that somebody is looking after the originals, in museums or whatever, and we should never take that for granted. I'm hoping Bill Blackbeard gets some recognition in the comics hall of fame this year. We should never undervalue the service that man has done for us. But for reading, it's all just information. And the way that takes up the least space is good for me.

MAUTNER: Apart from efficiency, did working more with computers and programs like Photoshop change the way you think about or approach making comics on any level, aesthetic or otherwise?

CAMPBELL: I think it probably has. On a thing that I'm working on now, which is a retrospective project, I had to recreate an image the way I would have done it twenty years ago. I couldn't believe the things I used to accept as okay, which the computer will not now allow me to accept. It was very frustrating trying to do it the old way. But i won't go into details. I could be wrong of course. We should always be alert to the possibility that the things we think of as advances are quite the opposite.

MAUTNER: I wanted to ask you about panel borders. In most of the Alec stories you tend to favor hand-drawn borders (as opposed to say Bacchus or The Playwright, where it's mostly ruled) In Stuff, however, the borders -- when you use them -- seem even rougher than usual and I was wondering if that was intentional and if so why?

MAUTNER: I wanted to ask you about panel borders. In most of the Alec stories you tend to favor hand-drawn borders (as opposed to say Bacchus or The Playwright, where it's mostly ruled) In Stuff, however, the borders -- when you use them -- seem even rougher than usual and I was wondering if that was intentional and if so why?

CAMPBELL: The issue at stake is that the pictures are very small in this book. Well, actually to begin with the page is small. I believe in giving the lettering plenty of room. You'd be surprised at the amount of time I spend on the lettering to make it look urgent but loose and dynamic. The pictures are very different, being very dense. So the frames mediate, putting the pictures in the same environment as the lettering. The relationship between the elements is always changing because if I change one thing, like doing the colouring on the computer, which takes the brushed-on dynamic out of it, then everything else must adapt.

MAUTNER: I find it interesting that you said that. What is your lettering process like and how did you develop it?

CAMPBELL: To call it a process is to flatter it. It's completely haphazard. I do it over until it feels right or I fall out with myself, whichever comes first. My idea of good lettering is George Herriman. It's beyond criticism. You couldn't take his lettering out and replace it with something else. That's not to say that there isn't somebody out there thinking about it at this very minute. Anyway, the lettering is always done first and everything else has to fit around that. I'll rewrite the script as I go along if I can't get the lettering into even lines. Somewhere down the line I start to think about the pictures, but at this stage in my career I only ever write a caption that already contains the suggestion of a picture to go with it. So everything falls into place very quickly.

MAUTNER: At the risk of spoiling part of the book, at one point you talk about the demise of the TV show based on your comics that was in pre-production. Despite the project's failure, would you rate the experience as a positive one? If the opportunity presented itself would you be willing to dabble in television (or some other filmed media) again?

MAUTNER: At the risk of spoiling part of the book, at one point you talk about the demise of the TV show based on your comics that was in pre-production. Despite the project's failure, would you rate the experience as a positive one? If the opportunity presented itself would you be willing to dabble in television (or some other filmed media) again?

CAMPBELL: We spent a couple of years developing that thing. It was a lot of fun. I learned heaps about how things get done in that business. Jeezis, but they waste a lot of time though. And I'm a glutton for punishment. Sign me up.

MAUTNER: What's your relationship with your publishers like these days? How much editorial input does Top Shelf have with your books or do they generally leave you to your own devices? Do you still have a relationship with First Second?

CAMPBELL: Top Shelf has got too much to worry about without trying to fix up my book. I was wishing somebody had helped me out with some harsh opinions, but I guess the book was all too overwhelming. So apart from a spell check, I’m pretty much left to my own devices.

First Second stuck their oar in much more. Mark Siegel is a great fellow, but I found the challenge of dealing with book publishers too much. I'm not just talking about First Second here. Random House did an edition of From Hell in Australia. The problem is that they have too many rules in the book business. There was a serious distribution problem with From Hell, by which I mean that the comic shops couldn't get it. That's a serious matter when you think about it. but I couldn't get into a position where I could discuss it with them with a view to solving the problem: "We don't discuss distribution percentages with authors." Things like that. Even though I was something more than an author, having published the book myself and got it into the places that they were having trouble with. I guess the rule book didn't have a procedure for that.

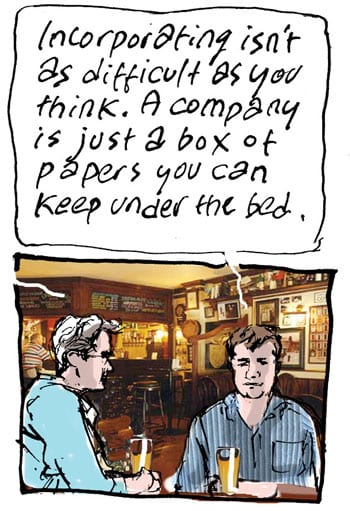

There were similar issues with First Second. I'll write a long essay about this somewhere and I don't really want to get into it here, but the book trade is hamstrung with so many ancient rules and regulations. Whether they're written or unwritten I couldn't figure out. Nobody would show me "the rule book." I have some funny stories about the schemes I would invent to circumvent some of the obstacles. The important point in all this is that a certain point in the evolution of "the graphic novel," the book trade interfaces with the comic book market. it's an interesting narrative ... for another time. Over a beer some time.

MAUTNER: How's the Complete Bacchus coming along? Is that still planned for publication in the near future?

MAUTNER: How's the Complete Bacchus coming along? Is that still planned for publication in the near future?

CAMPBELL: It's all done. they could send it to the printer tomorrow if they wanted, so you'll have to ask Top Shelf about that. [Note: Leigh Walton at Top Shelf said the book was probably still being formatted for publication.]

MAUTNER: You're pretty harsh on yourself in a few instances in Stuff -- your fights with your wife, with your kids, etc. Do you ever worry that you're not being fair to yourself or others or, taking the opposite view, are too lenient? Do you strive for accuracy when recreating events from your life or do you prefer to simply rely on memory?

CAMPBELL: I won't ask what parts you're referring to. More and more I'm finding that I can't bear going over things in my head. Now that it's on the page it would be nice to move on. But the crucial thing to remember is that it's all stories. Whether they happened to me or somebody else or didn't happen at all is not the important thing. The finished work is what counts. It's like using photo reference. If it makes the work better, then it's a good thing. Using real events is good if it makes better art. Changing events is good if it makes better art. It's not good if all it does is prevent hurt feelings. If I've used an event from real life it's because I know I could never make up things that say what that event says. It's like using a photo to get the turn of an ankle looking right, or the exact way things reflect in an eyeball. The only thing that matters is the work on the page.

MAUTNER: Finally, what's your impression of the current state of the comics industry? Do you think -- to bring it back to the subject of your latest work -- the world recession has drastically hurt things after what seemed like the start of a more widespread acceptance of the medium?

CAMPBELL: Comics are so awful that it's beside the point trying to figure out why the industry is weak. If comics were better then we might ask why these works of genius are not attracting a bigger audience. Let's wait till that question is worth asking.