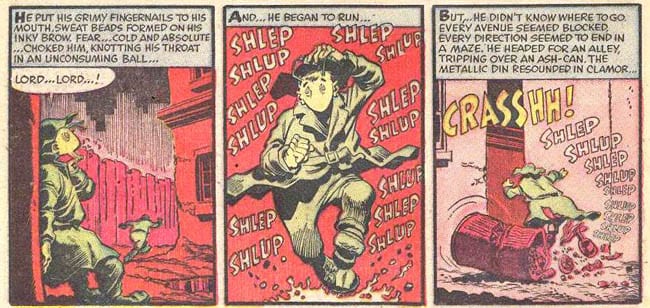

The final piece of the jigsaw fell into place a few months later. I walked into another room in Manhattan and glanced at a large marker-drawn caricature on the wall. There’s the signpost up ahead. Even before I stepped close enough to read the signature, I could tell, I knew, yes, this was a Nostrand original. And when I left there that night, I thought, yes, of course, he lives in Manhattan and what would happen if I simply opened the Manhattan phone directory? And, yes, I did this and there it was, yes, of course. Some weeks later I dialed the number, and so it came to pass one rainy Manhattan night in 1968, carrying my copy of Witches Tales #25 and an antiquated reel-to-reel recorder that felt like a small suitcase of rocks, I emerged from the subway bowels and went shlup-shlepping through the puddles on East 53rd Street to unmask the Mystery Artist. A solitary mission. An adventure. Funsies.

Now, at this time, my half-cracked plan was that I was doing this interview for Castle of Frankenstein magazine, which I had edited from 1963 to 1967. As I had introduced more and more comics-oriented features into CoF, this had finally reached a pay-off in 1967 when I pasted-up a “CoF Interview” with Stan Lee by Ted White as the lead piece (CoF #12, dated 1968) — and so it seemed that an interview with Howard Nostrand might make a good follow-up. So it seemed. However, there were several problems. One was that, as more and more comics and material about comics began to appear in the magazine, CoF publisher Calvin Beck, reflecting on the drop in sales of a 1966 issue with a TV Green Hornet cover, began to voice his objection. Then he voiced his objections to my objections to his objections. This was not exactly like Gaines and Kurtzman, but you get the idea: I thought his magazine was my magazine, and he thought my magazine was his magazine. As a result of these very literary discussions (which sometimes also concerned money), I made an exit stage right and found myself creating bubble gum cards, not CoF, in 1968 (and did not return to CoF until 1971). Perhaps Howard Nostrand glanced at some of the CoF issues during this period and wondered about the interview. But nothing appeared. Meanwhile, the battered tape-recorder was deep-sixed. The tapes were stacked with accumulated detritus and forgotten. Years passed.

The turning point might have been Graphic Story Magazine #11 (Summer 1970) with Hames Ware’s letter. But when this issue came out, I didn’t see it. And I also missed #12. Then, in the spring of 1971, Bill Spicer sent me GSM #13 which had a brief letter-column follow-up to the GSM #11 discussion of Nostrand I had missed. I casually wrote to Spicer asking if he had any interest in a Nostrand interview — and immediately received back an enthusiastic letter written in inch-high letters with a wide-tip marker (which I interpreted to mean a strong interest on his part). But then more time passed as I mailed the reel-to-reel tapes away to someone who transferred them to cassettes, for me. More delays followed as, late in 1971, I got involved simultaneously in the launching of Flashback magazine and spending hours at the drawing board on stories for Charlton’s Ghostly Tales. By February 1972, Spicer wrote, “How’s the Howard Nostrand transcript coming?” And in November 1972, with a note of desperation: “Your Howard Nostrand tape … if you want to send it to me, I can take the job of transcribing off your hands.” By the time I got into wrapping up the transcribing in the summer of 1973, Spicer was simultaneously planning the issue and also expressing doubt: “Not sure when the next issue ought to be out, except to say it should be a lot sooner than the time between this current number and the one before it. Approximately early ’74. So I suppose you’ve got at least a couple of months. I just want to be sure I’m going to get a transcription eventually … ”

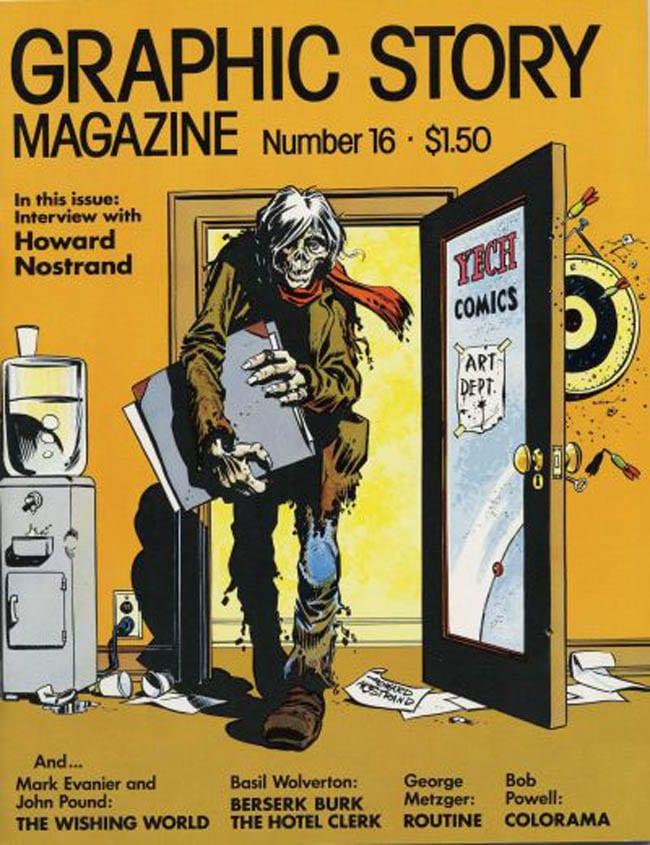

Finally, in October 1973, he received the interview, and a few months later (February 1974) Nostrand came through with Spicer’s requested cover for GSM — the first horror comics-type art he had executed in 20 years.

That same week Nostrand, with no advance warning, came up with a 56-page handwritten biography of his life from 1929 to 1956. I passed this on to Bill, who wrote back: “Laffed out loud about a dozen times reading Nostrand’s text the first time. It’s really too bad it can’t be printed in full somewhere, tho maybe someday … ” Because this had arrived unexpectedly at the last minute, when GSM #16 was almost all locked in, it was cut by about 50% in order to squeeze it into the issue. The full text of “Nostrand by Nostrand” has been restored for The Comics Journal.

Graphic Story Magazine #16, with the Nostrand interview, was published in the summer of 1974, the last issue of GSM. Bill Spicer, as early as 1973, had begun making plans for a publication with a wider scope, and he scheduled the letter column response to GSM #16 for the first issue of his new magazine. Three years passed. When Fanfare (subtitled “The Magazine of Popular Culture and All the Arts”) debuted in the spring of 1977, with letters of comment on Nostrand, almost a full decade had passed since I had gone shlup-shlepping through the puddles. It was a mixed bag of letters. Jerry De Fuccio, who was then still on the Mad staff, waxed nostalgic:

“Trial By Arms,” which Howard Nostrand brutalized, was written by me for Two-Fisted Tales #34. Harvey had yellow jaundice at the time. I also did the French Foreign Legion story, “En Crapaudine,” for John Severin in issue #34. John drew it in my Aunt Mary’s parlor, while he was wooing Michelina De Fuccio. Nice memories. I wish I could write “as well” as I did in those days. As for Graham Ingels, Nostrand’s patronizing remark that he was snuffed out with the demise of horror isn’t the whole story. Graham would deliver his work rather late at EC in 1951–52 when I started there. Everyone was gone for the day, and Graham and myself would have a cuticle of Scotch in Dixie Cups. I knew where Bill Gaines kept the liquor that was left over from the Christmas party. Bill knew I knew where he kept the liquor. Graham would sit — and sip — and admonish me that the comics were an ignoble business. He had been an editor for Ned Pines. Along with his good friend, Rafael Astarita, Graham was obliged to touch up a large quantity of very bad art which publisher Pines had bought very cheaply from “artist” Ken Battefield. I know how demeaning that must have been, as I couldn’t tolerate Battefield’s presence in a comic book when I was a paying customer. Graham had sufficient verve at Fiction House, and it is evident in his Sea Devil originals which I own. I suggest he was demoralized at Standard Publications and by Ned Pines. Fortunately for me, I never found out how “ignoble” the comics biz was because I’ve worked for Bill Gaines.

Landon Chesney, down in Chattanooga, stopped snarfing in his beer long enough to question Nostrand’s remarks on Harvey Kurtzman’s cartoonery:

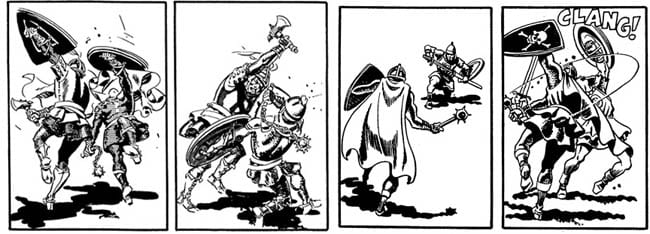

Hearing of an interview with some artist on the Harvey staff who we had all mistook for Jack Davis in the 1950s, I snarfed quietly in my beer, knowing full well I’d scanned EC’s competition well enough — mostly for laughs — to know that no one on Harvey’s payroll could be remotely confused with Davis. As it turns out, Nostrand, if the mood was on him, could be confused with virtually anyone on the EC staff. Really amazing work. So much so, in fact, that the big question, as in the cases of Basil Wolverton and Russ Heath, begs answering. Why didn’t they work for EC? Nostrand, to my knowledge, is the only one of the three who’s had the question to put him directly. His answer seemed vague, to say the least. His Wood parody (somehow “parody” is lacking semantically) is a genuine tour de force. He not only caught the superficial quirks of Wood’s style, which has been done often enough, but the actual spirit of it — certainly much more so than either Sid Check or Joe Orlando, Wood’s so-called protégés. Even more staggering is the takeoff on Kurtzman, whom Nostrand professes to dislike. I keep asking myself if I would have been fooled, not knowing in advance that the material was by Nostrand. I think it’s a fair bet that coming on these stories unaware I would have taken either for the original. Nostrand’s block on Kurtzman I still can’t figure out or even rationalize. His slant on everything else dictates the contrary. Kurtzman is an artist’s artist. It takes an artist, or a fan with a strong sense of artistic sensibilities, to appreciate that his stuff, which often goes beyond the ordinary license of comic book impressionism, is still “true” and very much in the classic comic book tradition. Kurtzman uses a kind of cartooning shorthand — which I understood would put off or even antagonize the layman, the casual comic reader — but it particularly troubling in Nostrand’s case because while he is not a layman, his objections are stated in those purely superficial terms. It takes an artist, and not a strict realist, to appreciate that the spirit of Kurtzman’s loose depictions of weaponry, for instance, was sometimes truer than the most uncompromisingly accurate drawing. Especially if the weapon is firing. Kurtzman would draw the gun in terms of its kinetic energy, which for his purposes was truer than the way it would look if you just copied it sitting on a table and then drew flames spewing from the barrel. It’s these little touches that you would logically expect Nostrand as a pro, and particularly as an EC fan, to appreciate. As for the interview itself, it was interesting, but not engaging. Not in the same sense that the interviews with Bernard Krigstein and Alex Toth were about as near perfect as you could hope for … The interviews with Wolverton, Nostrand and John Severin all seemed to share an underlying sense of uncertainty; they seemed to be on the verge of discussing their influences and their opinions, but never quite letting themselves go. It’s like Hitchcock discussing the suspense film in terms of distribution problems …

Nostrand’s high regard for Kurtzman as a writer-editor, however, is evident in “Nostrand by Nostrand” — where a paragraph about Kurtzman originally deleted from GSM for space reasons has now been replaced. There was EC work by Heath (Frontline Combat, Mad) and Wolverton (Mad, Panic). Referring to his features in Mad, Wolverton once wrote to me: “I regard this as some of my best work.” Obviously, Chesney means: why didn’t they have regular story assignments? In Wolverton’s case, not only was he located across the continent from the EC offices, but he preferred to illustrate his own writing.

Kenneth Smith, creator and publisher of Phantasmagoria, commented on Nostrand’s cover for Adventures in 3D, a leopard that Nostrand claims to have flopped and redrawn, with added muscles, a leopard from a Canadian Club advertisement:

… It was the material on Howard Nostrand that was most captivating. I too have long been curious about that fine little “8:30 PM” and other of his contributions to Harvey Comics, and I want to express heartfelt thanks to you for clearing this mystery up. Nostrand’s frank and bitter comments on the comics industry, gave a much truer picture than one tends to find in published remarks from comic artists who, still being in the employ of these feudal barons, have to hedge their comments … I wondered why one of his most widely publicized pieces of work went unremarked. Surely Nostrand himself must have noticed that the leopard he drew for the cover of Adventures in 3D #1 (1953) enjoyed renewed life in 1960s politics, apparently copied and inked-in solid as the symbol of the Black Panther Party. The variations from the Harvey cover to the Black Panther Party drawing (curve of the tail, cruder curves on the musculature, neglect of the portion of the torso seen between the right forearm and the jaw) are not so considerable as to undo the overall similarity in posture, particularly the unusual angles at which the two forepaws relate to one another. The Ringling Brothers poster, to me, displays merely a common theme and not necessarily any evidence of derivation or influence: The extreme difficulty of foreshortening (so dramatic and harmonious on the comics cover) is hardly present at all on the circus poster, and no portion of the cat’s anatomy is really similar from the Harvey drawing to the Ringling poster, not even the nose or lower lip. Of course, there may be a much more relevant version of the circus poster from the years prior to publication of the 3-D comic.

Funnyworld editor Mike Barrier (who had just relocated from Little Rock to Atlanta’s Barkston Court to Alexandria, Virginia), quoted from the interview’s original introduction as he tossed this into the hopper:

Hames Ware has made me aware, in conversations with him, of just how many rotten people there were in comics back in the ’40s, and Nostrand’s interview certainly confirms that. It’s good to have his testimony, but I was continually aggravated by the manner of its presentation. Bhob Stewart may think it was “necessary to leave in many of Nostrand’s digressions and sentence fragments,” but he’s wrong. The effect in print is not that of an “explosive speech pattern,” but of a typographical jumble. He could in fact have conveyed that “explosive speech pattern,” but only through careful editing, and not through a verbatim transcript. After all, a Nostrand tape is not the same as a Nixon tape; word-for-word ßaccuracy isn’t important — but the overall effect is, and the overall effect too often verges on incoherence. I’m sure that’s not the way Nostrand impressed Bhob, nor the way Bhob wanted to present him to us. The footnotes are equally annoying, ranging as far-afield as they do. This is “scholarly overkill,” with a vengeance. The larger problem I have with the interview is that it is difficult for me — on the basis of the evidence presented — to take Nostrand very seriously as an artist, whatever his merits as a man and a conscientious craftsman. Bhob’s approach reminds me too much of those people who dissect B movies with great care and discernment, overlooking the important point that those movies, when considered as they were meant to be considered — as wholes — are terrible pieces of junk.

This necessitated a clarification from Hames, back in Little Rock, which appeared in the letter column of Fanfare #2 (Winter 1978):

Mike Barrier says I made him aware of some rotten people in comics, and I feel I need to clarify this.

In researching for the Who’s Who [of American Comic Books, published 1973–76], a great number of artists and writers of the 1940s shared bitter memories of seedy fly-by-night people who demanded kickbacks, refused to pay for work rendered, etc. Most individuals were reputable, but a surprisingly large number of creative people who worked in comics hold very bitter memories about the several who weren’t.

For someone who has credentials in pop culture criticism, as Barrier does, his main argument was rather startling. It ignores such filmmakers as Edgar G. Ulmer, who, within the limitations of low budgets and four-to-six day shooting schedules, set out to “create art and decency, with a style” (as Ulmer put it). Ulmer spent a lifetime in B films and chose to do so because of the artistic freedom: “… I knew [Louis B.] Mayer very well, and I prided myself that he could never hire me! I did not want to be ground up in the Hollywood hash machine.” Yet today prints are lost and even the titles are unknown for many of Ulmer’s 128 films (his count), and part of the blame for this can be directed at writers about film who were duped by Hollywood hype to the extent that they ignored artists such as Ulmer in favor of churning out reams of copy on A-budgeted films, serving as second-generation publicists while they rehashed press releases. It was this situation that led painter/art critic/film critic Manny Farber to write, in 1952, an article titled “Blame the Audience” for Commonwealth:

In the past, when the audience made underground hits of modest B films, Val Lewton would take a group of young newcomers who delighted in being creative without being fashionably intellectual, put them to work on a pulp story of voodooists or grave robbers, and they would turn $214,000 into warm charm and interesting technique that got seen because people, rather than press agents, built its reputation … Once, intellectual moviegoers performed their function as press agents for movies that came from the Hollywood underground. But, somewhere along the line, the audience got on the wrong track. The greatest contributing cause was that their tastes had been nurtured by a kind of snobbism on the part of most of the leading film reviewers. Critics hold an eminent position, which permits control of movie practice in one period by what they discerned, concealed, praised, or kicked around in the preceding semester of moviemaking. I suggest that the best way to improve the audiences’ notion of good movies would be for these critics to stop leading them to believe there is a new “classic” to be discovered every three weeks among vast-scaled “prestige” productions. And, when they spot a good B, to stop writing as if they’d found a “freak” product.

At the time Barrier wrote his letter, books on B movies had only just begun to appear — Gene Fernet’s 1973 Hollywood’s Poverty Row, 1930-1950 (Coral Reef Publications) and Don Miller’s “B” Movies (Curtis Books, 1973), both titles that were somewhat difficult to track down even in 1973. A year after GSM #16 the full illumination of the B movie arrived with the 561-page Todd McCarthy/Charles Flynn-edited anthology, Kings of the Bs (Dutton, 1975), my source for both the Ulmer quote and the Farber passage above. Although French film critics had written about the American B-budgeted film noir as early as 1946, decades passed before critical snobbism in this country gave way to a lengthy full-scale examination of the subject with the Alain Silver/Elizabeth Ward-edited Film Noir (Overlook Press, 1979), an encyclopedia which, for all of its flaws, is currently being used as a guidebook by many TV viewers who now understand how they had been misled by mainstream critics selling the Hollywood party line. But the critical study that best repudiates Barrier’s “terrible pieces of junk” dismissal is the shadow waltz of Foster Hirsch’s evocative The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir (A.S. Barnes, 1981) which fully defines how “the noir canon is an exemplar of Hollywood craftsmanship at its finest.” In examining the lithographs/paintings/photographs/films/novels that influenced or anticipated film noir Hirsch plunges across the pitch black landscape of Cornell Woolrich, author of stories and novels that became the sources for countless movies, radio dramas, and TV thrillers:

Hammelt, Chandler, Cain, and McCoy wrote novels and stories that inspired some of the most highly acclaimed films noirs. But the writer whose sensibility is most deeply noir —Cornell Woolrich — does not have the literary prestige of the hard-boiled quartet. The pulp base of Woolrich’s style is less disguised than in the writing of the others, but Woolrich is a better storyteller than Hammett or Chandler and a master in building and sustaining tension.

Which brings us to the Woolrich comics connection — for the Woolrichian desperation that underlies film noir (so strongly that even a non-Woolrich-based film such as Ulmer’s 1946 Detour seems like Woolrich) was also captured in claustrophobic noirish panels by Eisner, Nostrand, EC’s Johnny Craig, and others. After Woolrich’s March 1947 Mastery Book Magazine novelette “The Boy Cried Murder” (a.k.a. “Fire Escape”) became Ted Tetzlaff’s 1949 film The Window, it was then adapted into comics for the seventh issue of Seaboard Publications’ Famous Authors Illustrated/The Window (1951), illustrated by Henry Carl Kiefer (1890-1957), best known for his Classics Illustrated books but also an illustrator of crime/Western stories for EC (War Against Crime!, Saddle Justice, Crime Patrol, and Gunfighter) plus art for more than two dozen different publishers between 1935 and the mid ’50s. Writing about Kiefer’s Window in an article titled “Film Noir and Comic Books” (Fanfare #2), Carl Macek (one of the contributors to the Film Noir encyclopedia) commented, “Kiefer was able to respond to the abundance of noir elements present in films and other artwork of that period. Regardless of whether Kiefer went to the movies looking for images, they found their way into his work. There isn’t a great deal of slickness to Kiefer’s art, yet it manages to capture in this assignment some of the film noir flavor.” EC’s “A Hollywood Ending!” (illustrated by Joe Orlando for Tales from the Crypt #30), in which a beautiful reanimated dead woman begins to decay, is a variation on the “dying alive” and decaying Jane Brown/Nova O’Shaughnessy of Woolrich’s horror-suspense novelette, “Jane Brown’s Body,” originally in a 1938 issue of All-American Fiction, recently reprinted in The Fantastic Stories of Cornell Woolrich (Southern Illinois University Press, 1981) and televised (a week after Woolrich’s death) on the British anthology TV series Journey to the Unknown (October 2, 1968).

Woolrich was also an influence on the Jules Feiffer/Will Eisner script collaborations for The Spirit. In one of Feiffer’s earliest scripts for Eisner, the June 5, 1949 “Black Alley,” the Spirit chases a killer from a darkened third-floor tenement room onto the elevated tracks a few feet from the window. This was a reverse switch on the situation of Woolrich’s October 10, 1936 Detective Fiction Weekly short story “Death in the Air” which opens with Inspector Step Lively seeing a train passenger hit by a bullet, pulling the emergency cord and then running down the El tracks to enter a darkened tenement room. The anthology radio series Suspense (which featured Joe Kearns as “The Man in Black”) began on CBS in 1942, and throughout the ’40s it broadcast many adaptations of Woolrich stories (including some adapted by Woolrich himself). Regarding Suspense as “a program that affected me an awful lot and taught me a lot about writing,” Feiffer (in Panels #1) recalled this Woolrich influence:

… That’s out of a tradition … which I was conversant with, the stories of Cornell Woolrich and James M. Cain. Where you take an ordinary guy, and he says, “Honey, 1 can’t sleep. I think I’ll go downstairs and pick up tomorrow morning’s Daily News.” And she never sees him again. Woolrich just took people in very ordinary circumstances and entered them into violence, which is something that Eisner also did from the beginning. And it fascinated me when I read it in Eisner, it fascinated me when I read it in pulps when 1 was a kid, and listened to Suspense, which used to dramatize a lot of them.

Criss-crossed chiaroscuro, extreme angles, distorted shadows, low-key lighting, flashbacks within flashbacks, frames within frames, deserted cityscapes, rain-glistening streets, mirror reflections, peeling wallpaper in furnished rooms, subway entrapment, neon nightclubs. These were the visual stylistics of film noir. In choosing to create such stylistics on paper, Eisner and Nostrand both fashioned narrative art that is inextricably linked to and derivative of film noir. Woolrich, who sometimes wrote under the pseudonym William Irish, was also the only writer cited by scripter-artist Johnny Craig when Craig was asked by John Benson to name some favorite writers: “I remember William Irish as being an excellent short story writer. I think many of his things had been adapted for radio.”

In addition to the tales “well calculated to keep you in Suspense,” radio listeners of the ’40s could choose from a weekly line-up of several terror/adventure/suspense/thriller anthology shows such as The Whistler with its sombrous omniscient introduction: “I am the Whistler. And I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes, I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak.” (This was parodied by Spike Jones: “I am the Whistler, and I walk by night. I have to. I can’t sleep.”) When The Whistler radio series was developed into a film series, two of these features — Marie of the Whistler (1944) and Return of the Whistler (1948) — were adapted from stories by Woolrich.

The device of a horror host was also heard on The Mysterious Traveler (which began on the Mutual network in 1943) and Inner Sanctum (which made a Jan. 7, 1941 debut on the NBC Blue network). And listeners also tuned in to Lights Out (“It is later than you think … Lights out, everybody!”), The Hermit’s Cave (“Ghost stories, weird stories and murders too. The Hermit knows of them all. Turn out your lights. Turn them out!! Ahhh …”) and Escape (“Tired of the everyday grind? Ever dream of a life of romantic adventure? Want to get away from it all? We offer you … Escape! Designed to free you from the four walls of today for a half-hour of high adventure.”).

By inviting listeners to kill the lights, these shows acknowledged what was, I suspect, a common practice. While other media required lights, radio drama did free its audience from four walls — broadcasting to children stretched out on carpets by radio consoles in darkened living rooms, listeners lying in beds near the faint illumination from table radios, or lonely night drivers on deserted highways. The radio audience included many comic creators, including Bill Gaines and Johnny Craig; as Craig explained, “Bill and I had remembered The Witch’s Tale and Lights Out from radio, and we tried it out in the comics.” Written and directed by the pulp author Alonzo Deen Cole, The Witch’s Tale premiered on the Mutual network in 1934. The show opened with sounds of a tolling clock, howling wind, and menacing music as the announcer read, “The fascination for the eerie … weird, blood-chilling tales told by Old Nancy, the Witch of Salem, and Satan, the wise black cat. They’re waiting, waiting for you now …” Then, while Satan meowed in the background, Old Nancy launched into the story introduction. According to Bill Gaines, it was Old Nancy and not the horror hosts of the ’40s which directly inspired the Three GhouLunatic horror hosts of the EC horror comics.

Radio drama and comic books are direct opposites. Radio drama has sound effects, spoken dialogue and music — but no pictures. Comics have pictures — but no sound. These complementary aspects encouraged tie-ins, beginning in the ’30s with comic strips. Sometimes the radio series would dramatize the plotline directly from the comic strip. Many strips and syndicated features got the aural treatment: Ripley’s Believe It or Not (NBC, 1930), Blondie (CBS, 1939), Bringing Up Father (with Agnes Moorehead as Maggie), Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (heard from 1932 to 1939 and revived in the mid-’40s), Buster Brown (CBS, 1929, sponsored by Buster Brown Shoes, which had acquired rights to use R. F. Outcault’s 1902 strip character), Dick Tracy (Mutual, 1935), Don Winslow of the Navy (NBC Blue, 1937), Hash Gordon (Mutual, 1935, with Gale Gordon as Flash), Gasoline Alley (heard on the radio in the early ’40s and seen in movie theaters in 1951 as a feature film from Columbia), The Gumps (CBS, 1934, co-scripted by Irwin Shaw, with Agnes Moorehead as Min), Carl Ed’s Harold Teen (1941), Ham Fisher’s Joe Palooka, Jungle Jim, Al Capp’s Li’l Abner (NBC, 1939, with John Hodiak in the title role and Durward Kirby announcing), Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie (NBC Blue, 1931), with Sandy’s “arfs” by Brad Barker — get it?), Major Hoople (adapted from Our Boarding House, created by Gene Ahem, this early ’40s show featured Mel Blanc as Mr. Twiggs), the Lee Falk/Phil Davis Mandrake the Magician (Mutual, 1940, with Inner Sanctum host Raymond Edward Johnson in the title role), Ed Dodd’s Mark Trail (Mutual, 1950), Mayor LaGuardia Reads the Funnies (Sunday comics sections read by NYC’s mayor during a 1945 strike by newspaper deliverers), Clare Briggs’s Mr. and Mrs. (CBS, 1929), The Nebbs (from the Sol Hess strip and starring Gene and Kathleen Lockhart), E.C. Segar’s Popeye the Sailor (NBC, 1935, with Mae Questel as Olive Oyl), Fred Harman’s Red Ryder (with Reed Hadley in the title role), Gene Byrnes’s Reg’lar Fellers (with Dick Van Patten and Skip Homeier), George Baker’s The Sad Sack (CBS), Percy Crosby’s Skippy (NBC, 1931), Zack Mosley’s Smilin’ Jack (starring Frank Readick, who actually wore a cloak and mask when he portrayed The Shadow on radio of the early ’30s), Strange as It Seems (CBS, 1939, adapted from the John Hix syndicated feature), Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates (NBC, 1937, with Agnes Moorehead as the Dragon Lady), Tillie the Toiler (from the Russ Westover strip), and H.T. Webster’s The Timid Soul (with Superman announcer/narrator Jackson Beck as “the druggist”).

In the titles listed above, the comic strips came first. The radio programs were adapted from the more successful strips. In the comic book field, this situation was usually reversed. With some exceptions as noted, comic books were adapted from radio series, and these comic books sometimes began publication several years after a program had developed into an established long-run property: The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (which began on CBS in 1944 and originally had actors Joel Davis, Henry Blair, and Tommy Bernard portraying David and Ricky), The Aldrich Family (NBC Blue, 1939), Archie Andrews (heard on Mutual two years after the character appeared in the December 1941 Pep Comics), The Bing Crosby Show (1946), Blackstone, the Magic Detective (with Ed Jerome as Blackstone), Bob and Ray (whose routines were illustrated in Mad magazine), Blue Beetle (aired twice-weekly not long after his leap from a Mystery Men feature to his own title in 1940), The Bob Hope Show (NBC Blue, 1934), Bobby Benson’s Adventures (CBS, 1932, with Don Knotts as Windy Wales), Captain Midnight (Mutual, 1940, which spawned a short-lived imitator, Captain Sparks, on the Little Orphan Annie show), Casey, Crime Photographer (CBS, 1946, adapted by Alonzo Deen Cole from the mystery novels of George Harmon Coxe), Challenge of the Yukon (ABC, 1947, which led to Dell’s 1951-58 Sgt. Preston), Charlie Chan (NBC Blue, 1932, also in strips, comic books, and films), Cisco Kid (Mutual, 1943), The Clyde Beatty Show, The Colgate Sports Newsreel Starring Bill Stem (1939 to 1951), A Date with Judy (NBC, 1943, with the comic book arriving in 1947, a year before the movie), The Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show (NBC, 1936), Gangbusters (CBS, 1936, based on true stories), Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch (CBS, 1940), Green Hornet (Mutual, 1938 — with Captain Video’s Al Hodge in the lead and, later, Mike Wallace as the announcer), Gunsmoke (CBS, 1955, with William Conrad as Matt Dillon), Hop Harrigan (ABC, 1942, adapted from the feature that began in the debut 1939 issue of All-American Comics — and later made into a 1946 movie serial), Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy (CBS, 1933 to 1951), Jane Arden (1938), The Jimmy Durante Show, Land of the Lost (ABC, 1944, with Art Carney as the glowing fish Red Lantern), Let’s Pretend (CBS, 1934), The Lone Ranger (Mutual, 1933 to 1954), The Martin and Lewis Show (NBC, 1949), Meet Corliss Archer (CBS, 1943, with the 1948 comic book illustrated by Al Feldstein), Mr. District Attorney (NBC, 1939), My Friend Irma (CBS, 1947, with the movie following in 1949 and the comic book in 1952), The Mysterious Traveler (Mutual, 1943, with the comic book arriving five years later), Nick Carter, Master Detective (Mutual, 1943, adapted from the Street and Smith pulp character whose adventures began in 1886), Perry Mason (CBS, 1943), Roy Rogers (1944 to 1955), The Saint (NBC, 1944), The Shadow (Mutual, 1937, after the character was introduced on The Detective Story Hour in 1930), Songs of the B-Bar-B (the music and comedy version of Bobby Benson’s Adventures), Straight Arrow (Mutual, 1948 — with the Magazine Enterprises comic book running from 1950 to 1956), Superman (heard on Mutual in 1940, two years after Action #1, with Bud Collyer in the title role and occasional appearances by Gary Merrill as Batman), Tom Mix (NBC 1933 to 1950, with Tom Mix comics free in exchange for a Ralston boxtop, in addition to the Fawcett Tom Mix Western published from 1948 to 1953).

Personalities, such as Durante and Hope, were also seen on TV and in films, but in many cases the comic book was the only visual reference for a radio comedy or drama. Such tie-ins may have been strongest in the case of Isabel Manning Hewson. As scriptwriter, narrator and producer of the Land of the Lost radio show, and writer of EC’s Land of the Lost comic book (illustrated by Olive Bailey), she maintained a consistency of characters and stories in both, duplicating the storylines (plus receiving credit for story in the 1948 animated short). In addition, she also appeared as a character, herself as a little girl, in both comic and radio versions.

Howard Nostrand was right in the middle of this comic book/radio series interface, as pages emerging from the Powell studio included an array of radio characters — The Whistler, The Mysterious Traveler, The Shadow, Nick Carter, Straight Arrow, Green Hornet, and Bobby Benson’s B-Bar-B Riders. In addition to Nostrand’s mentions of these tie-ins, he also described a sub-genre of comic book features (“Tommy Tween,” “Red Hawk”) inspired by successful radio formats.

Despite Nostrand’s negative response to the question, “Do you have any desire to return to comic books?” only a few months after the 1974 publication of the interview, he returned to comic books, producing pages for Martin Goodman’s Seabord Publications (Atlas) and Crazy magazine.

In retrospect, Mike Barrier’s comments on the editing of the transcript have some validity, so, this time around, it has been re-edited even further — streamlined for easier reading, although these are only minor deletions. The footnotes that Barrier found “equally annoying” have been expanded considerably to annoy Barrier even more.

Image of a man without a name, leaning over a drawing board. Here are some of the jigsaw pieces scattered about, and if there are missing pieces, we leave that up to you. This we offer as a small exercise, an extracurricular diversion. For any further research, check under “C” for “cartoonist” in … The Nostrand Zone.