The name Garo is a mystery. The word does not belong to standard Japanese. It is not a known loan word, despite being in katakana.

Back in the early 1970s, esteemed cultural theorist Tsurumi Shunsuke noted that the name, with its “avant-gardistic” feel, sounded like Spanish or Italian.

Not ten years ago, manga and film scholar Yomota Inuhiko noted that it was regional dialect for kappa, a water imp who abducts children and horses and drowns them in the river.

Speaking with Japanese fans and scholars, it seems that many accept Yomota’s theory. I’m not sure why. While indeed “garo” can be found in books dealing with the kappa – it is derived from “kawa tarō,” River Tarō, the latter half a generic boy’s name – none such that I have seen were published prior to the naming of Garo in 1964. Of the major sources on the Japanese supernatural that would have been available to Shirato at the time – the writings of Inoue Enryō, Yanagita Kunio, Ishida Ei’ichirō – in none of them is that specific pronunciation for kappa to be found. Of course, it is always possible that Shirato heard it directly from someone from the countryside. Or perhaps from a colleague more versed in Japanese folklore, like Mizuki Shigeru. After all, Mizuki did publish an eight-volume rental kashihon series between 1961 and 1962 titled Sanpei the Kappa (Kappa no sanpei), about a human boy that looks like a kappa and as a result has serial run-ins with yōkai. Towards the end, his kappa stand-in is named “Kawa Tarō,” but no “garo.” The title of the manga might seem suggestive, but Sanpei is a common enough name for it to have nothing to do here with Shirato. And since Garo was Shirato’s magazine, not Mizuki’s, it seems to me highly unlikely that the former would title his greatest publishing venture after a creature that has (as far as I can recall) never made an appearance in his work. Shirato was greatly indebted to Japanese myth and folklore. But the cosmologies of ghosts and monsters are at best minor ones in his pantheon.

A recent book should have put the issue to rest. Writer Mōri Jinpachi has been close to the reclusive cartoonist for many years. In 2011, he published The Story of Shirato Sanpei, part biography and part manga history, composed substantially of paraphrases and direct quotes from the horse’s mouth. On the origins of the name Garo, Mōri is specific: “The name of the magazine Garo comes from a ninja in one of Shirato’s works. In addition to resonating with the word garō, meaning one’s own path, he says that he also had in mind the name of an American mafia gangster. From a list of options, it was [Garo’s publisher] Nagai Katsuichi’s nephew who finally chose the name.”

Inspiration from the word garō, written with the characters ware (first person pronoun singular or plural) and michi (path, road), is not implausible. But Japanese are not typically inclined to drop a “u” to convert a long vowel into a short one. Moreover, garō is a robust-looking word in kanji. Why change the spelling and convert it to katakana?

As for the American mafia, (I ask in earnest) to whom could he be referring? Keep in mind we are dealing with the early 60s. Not only was straight gangster material on the wane at the time, but it was not a genre in which Shirato demonstrated any interest. He was obviously a champion of armed rebels and outlaws, yet it seems unlikely that he would have adopted the name of an obscure American criminal for his own magazine. Even if Shirato did say it, I am not convinced. After all, we are talking about testimony forty-five long years after the fact.

What we do know for certain is what Mōri mentions first, which is that Shirato used the name for a character in a story a year and a half prior to Garo the magazine’s founding in September 1964. This might be a better place to start.

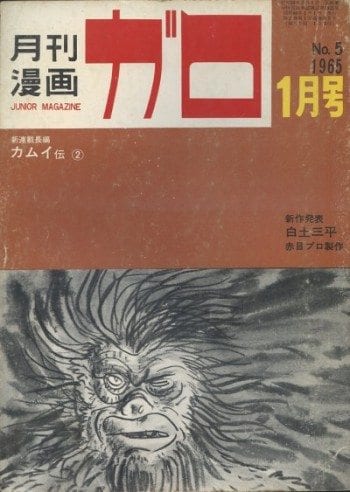

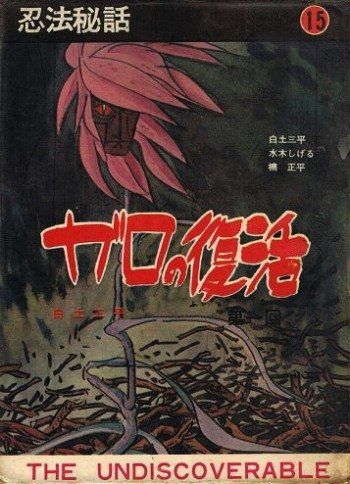

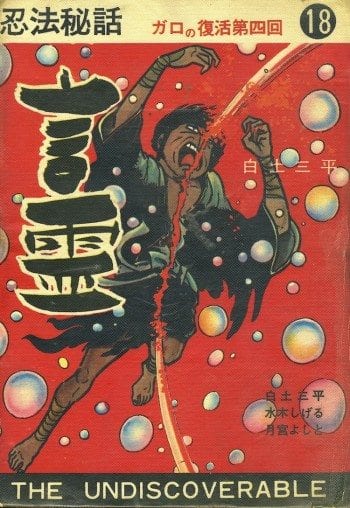

The venue was Secret Tales of the Ninja Arts (Ninpō hiwa, 1963-65), a Shirato-centered kashihon anthology published semi-monthly by Seirindō, the future publisher of Garo. It is often considered the precursor of the legendary magazine, and justifiably so. Amongst the contributors were Mizuki, Kojima Goseki, Kusunoki Shōhei, Ogawa Akira, and Doya Ippei, mirroring the roster of early jidaigeki-heavy Garo. A “special edition” of Ninpō Hiwa issued in January 1965 was composed of Shirato’s pages from the first three issues of Garo – not the original artwork, the actual printed pages, detached and rebound. Something had to be done with the many unsold copies.

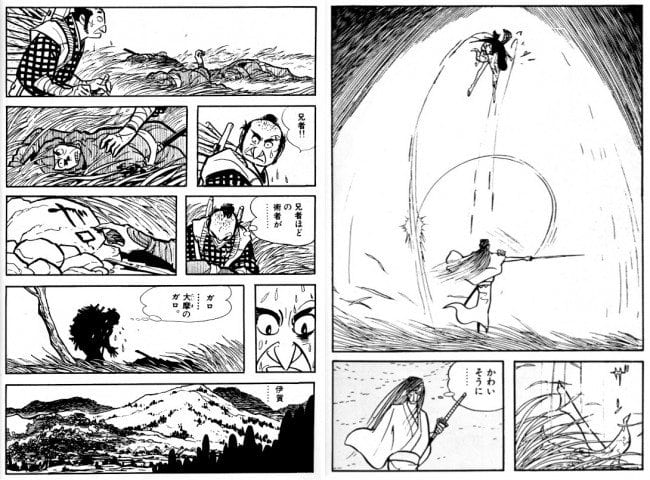

A number of Shirato’s contributions to Ninpō Hiwa starred a mysterious and deadly ninja named Taima no Garo, the first term being a Sinicized rendering of the Sanskrit “Maha,” meaning “great.” So: Maha Garo, or The Great Garo. Debuting in volume no. 8 (published March 1963), at first Garo is nothing but a blur, his passage known only second-hand from corpses and spraying blood. Dead ninja are impaled upon trees. Others lie littered across the field. With his dying breath, one victim managed to write the name of his executioner in blood upon a rock. Two letters in katakana: GA-RO.

Though clearly not a practitioner of non-violence, Garo is at heart a peaceful man. He is tall, gaunt, aged but not old, with thin long-flowing hair, living with his son and spending much of his time sculpting masks, busts, and limbs out of wood. It is the local Iga ninja clan that wages war upon him, a renegade living on the outskirts of their domain. Garo has killed many of the Iga brotherhood in defense. It is suspected that he has also associated with Oda Nobunaga, their enemy. All matter of swords, throwing stars, and incendiaries fail to extinguish Garo. But eventually, in the second issue of his appearance, they find a way of killing him through allergens, a signature touch from Shirato the naturalist.

It does not seem that initially Shirato invested anymore in this character than he had in others. The first stories are rather undistinguished, just two more installments on top of the artist’s extensive ninja manga pile. But in January 1965, Garo is brought back for another round, this time of five chapters. The inauguration of the magazine Garo the previous September presumably inspired its namesake’s revival, and indeed this run of Maha Garo seems to have had the pedagogical program of Garo the magazine in mind.

A strike of lightning brings Garo back from the semi-dead. Again he becomes the target of Iga assassins. Once again he proves hard to kill. But then a man from afar arrives and offers his services, a bonze named Warawa (meaning “Child”) from Negoro, home to famous warrior monks in the sixteenth century. Shirato had expressed vehement distrust of religion previously in The Legend of Kagemaru (1959-62) and Akame (1961-62). It is notable that it should manifest again here, in a battle with so-called “Garo.”

Every killer has his own caché of ingenious killing techniques. The Negoro monk’s is named “kotodama,” meaning “the spirit power of words.” It is essentially a method of hypnotic suggestion. The monk issues a bubble from his mouth. It floats through the air towards its target, and when it pops it triggers in the hypnotized subject the embedded response, in this case murder.

Shirato has endowed Garo with powers of “heart-reading.” His superiority as a fighter stems in part from his ability to know their intentions and next move before they act, making it near-impossible for an enemy to approach without Garo one step ahead. Those who are hypnotized, however, do not know what actions lay in their own hearts, making for the perfect weapons against Garo’s perspicacity. To make the attack even less anticipatable, the Negoro monk chooses as his subjects the many orphans that now live with “Garo ojisan,” Uncle Garo. They have been given pipes for making soap bubbles to play with. And when the first one bursts inside their home, the children snap to and plunge cooking skewers from all sides into Uncle Garo. He falls dead to the floor.

What is this “kotodama” that it should be so strong to defeat the invincible Garo? The term kotodama itself is an old one, appearing as early as the ninth century, in the court poetry collection the Manyōshū. There, building on ancient religious practices, it is used to connote the magical efficacy of ritual or poetic speech. For centuries, while the influence of Buddhism ensured that poetry was still often seen in similar terms, the term kotodama itself seems to have gone into abeyance. It was revived at the turn of the nineteenth century by Japanese nativist scholars, who saw in the idea the essence of a pure, transparent, and semi-divine Japanese way of speaking and writing, unsullied by foreign influence and historical degradation, and inspired directly by the Shintō gods. It is as such that the term found its way into the Kokutai no Hongi (The Essence of the National Polity), an infamous document first published in 1937 by the Ministry of Education and distributed to the teaching staff of both public and private schools, from the elementary to the university level, throughout Japan. Approximately two million copies were in print at the end of the war. It linked proper discourse directly with Emperor-centered fascism, casting the idea of kotodama – at least for those Japanese attuned to their country’s modern political history – into deep shadow ever after.

It is thus natural that “kotodama” should appear in Shirato’s work as the name given to a verbal emission – a physically literalized “speech bubble” – that mesmerizes youth and turns them against their ward. Shirato is here dramatizing his own trials as an artist. At the very same time as this story was running in Ninpō Hiwa, he was waging war through the pages of Garo against the recent reactionary turn of Japanese education, led by the reinstitution of moral education curricula in schools and the rewriting and censorship of textbooks in line with rightwing interpretations of Japanese history and society. Clearly the mercenary man of religion is a stand-in for the unprincipled contemporary educator and his dangerous powers of persuasion through speech. If the allegory was not clear enough, Shirato includes the following as an afterword to Garo’s death in June 1965: “The influence of education is great, and the responsibilities of educators heavy. If there are those who raise young saplings to become sturdy and strong, there are also those who manipulate children like puppets.”

While Garo the ninja had become a personification of the counter-pedagogical program of early Garo the magazine, I think there might also be a biographical link. Shirato’s father, Okamoto Tōki (1903-86), was a painter and an illustrator and a leading member of the prewar Proletarian Arts Movement. Uncle Garo is also an artist, sculpting when he is not fighting his foes, carving masks and toys out of wood. Okamoto evacuated his family to Nagano in 1944, and kept his children, as much as possible, away from the militaristic education at schools. Similarly, the isolated Uncle Garo is the caring guardian of orphans in the mountains. Okamoto was tortured by the Kenpeitai (the Japanese secret police) during the war, and physically never fully recovered. Uncle Garo is destroyed, and by whom?

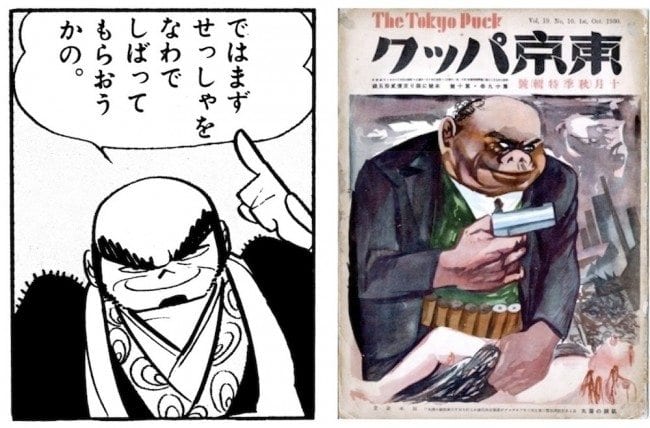

A kotodama master whose face is drawn almost exactly in the same manner – wide, balding, and pig-nosed – as Okamoto Sr. drew rapacious Capitalists for left-sympathetic magazines circa 1930. Was The Great Garo an homage to father?

(cont'd)