As illuminating as this might be of how Shirato thought of his magazine’s spiritual roots and role in the world, it does not address the core question. Where does the name Garo itself come from?

For this, I believe one has to go into very different territory: into the jungles of Meghalaya and neighboring Assam in northeast India, a scenic but strife-ridden region between Bhutan and the Indo-Bangladesh border. There you will find the verdant Garo Hills in India, named after the tribe that lives there, and in fewer numbers in the Mymensingh district of Bangladesh. These days, on the rare occasions that the Garo appear in Indian national media, it is usually in reports of violence against Bangladeshi immigrants, who are sometimes made to pay with their lives for encroaching on Indian tribal lands and taking their jobs.

It might seem quite a jump from Garo the magazine to the Garo Hills, as arbitrary as, say, Tsurumi’s thought that the name sounded Spanish or Italian. But in the early 60s, India’s northeast was not so remote from Japanese imagination. First of all, the general region would have been familiar to many as the westernmost reach of the Japanese military’s attempt to unify Asia under the Emperor. Defeat in the spring of 1944 in the Battles of Imphal and Kohima, on the eastern fringe of India, foretold the conclusive losses the Japanese would suffer in Burma and southern China. Meanwhile, the Garo, along with their neighbors the Khasi, became the subject of considerable anthropological interest as one of the last remaining matrilineal societies on earth. That’s matrilineal, not matriarchal. Power is in the hands of men in Garo society, but name and property descend via mothers and daughters. A man marries into a woman’s family. Kinship is determined by common blood on the mother’s side, not the father’s.

In February 1959, the general Japanese public was introduced to the Garo with the publication of Faces of Savagery, Faces of Civilization (Mikai no kao, bunmei no kao), a travelogue by anthropologist Nakane Chie, a scholar then just emerging, but by the late sixties well-known (and today ill-regarded) for her work on Japanese national social character. As recipient of the Mainichi Culture Prize, Nakane’s travelogue was widely publicized in its day. Narrating experiences between 1953 and 1957, it opens telling of Nakane’s adventures in the interior of Assam, before moving to Tibet, Calcutta, and then over to Europe. On the way back to Japan, she stops in Egypt and the Middle East. One might judge the South Asia segment Lonely Planet-like today. But in an age when only moneyed or grant-funded Japanese traveled overseas, Nakane’s difficulties in finding an interpreter, securing transportation, and accepting strange food and pungent liquor from curious hosts who had never before seen a Japanese woman – Japanese male soldiers had been plentiful in the region during the war – all of this would have struck readers as fresh and captivating. Certainly they would have found the promotional copy on the book’s wrapper (its obi) so. “The feasts of headhunters, a man whose wife is killed by elephants. Into the wild beast-infested jungles of the uncivilized tribes of India, a young female anthropologist travels alone. Thrills and passion overfill this, the record of her exploration.”

This obi, which makes the author sound like a Japanese Jane “Lady Greystoke” Porter, is really more representative of Faces of Savagery than the King Tut photograph on the first edition’s cover. Abstracting from Nakane’s experiences in the Garo Hills, that text casts her travels in the tropes of Imperial era adventure literature, which is and is not fair. Her entourage of porters, a cook, and a strapping local guide, the ruddy village headman who scrutinizes her Western dress, hunting tigers with a local official, drunken dancing around a bonfire – these details do indeed sound like they could have come from colonial explorers fifty years prior. But Nakane’s adventure is constantly clipped by unromantic details of social anthropology and recent colonial history.

The people of northeast India are at the center of this tempered adventure. She explains about the Garo, “Like the Japanese and Chinese, they are of Mongoloid stock. Their color is light black. Their height is roughly that of the Japanese. They appear cheerful and trustworthy. They were all intensely curious about the fact that I had travelled alone all the way from Japan. The name ‘Japan’ was not new to them, for most of the tribes in Assam were familiar with the fact that the Japanese military had come as far as Imphal. Many of the uncivilized tribes living in Assam were headhunters until recently, so they speak with great respect of the ‘courage’ of Japanese soldiers.” To the Naga peoples in Manipur further east, upon whose lands the Burma Campaign was actually fought, Nakane finds herself apologizing for the Japanese army’s plunder of food stores during World War II. “Had I been a man, I think they might have killed me.” Others spoke, like the Garo, of Japanese soldiers’ bravery. “They [the Naga] still remembered words like nippon, tennō, and banzai.” One family urged Nakane to use a pair of chopsticks left behind by a Japanese soldier. Know that she went to the Naga Hills in 1954; the Battle of Imphal was recent memory for her informants and readers alike. Meanwhile, because of the lighter color of her skin, most Garo assume Nakane to be Christian – catching her in the crossfire of overlapping colonial histories.

Nakane travelled to India to study kinship systems. She is peppered with questions about how the Japanese grow rice, how houses are made, but most of all how marriages work. Nakane was publishing academic articles in Japanese at the time on the subject of matrilineality amongst the Garo and Khasi, culminating in the release of an English-language book in Europe in 1967. In Faces of Savagery, research is given a casual face. “I explained that, in Japan, the wife is adopted into the husband’s family, that the children also take on the husband’s family name, that property belongs to the husband, and that the wife is expected to be submissive to her husband. Everyone cocked their heads to the side, saying what a bad system that is. Since women are weak, they should own property, as they do amongst us. We feel sorry for Japanese women, they said.”

Given Shirato’s interest in blood not just of the splattering sort but also of the genetic and familial kind, it is possible that even this relatively minor, academic feature of Faces of Savagery piqued his interest. Granted, a manga like The Crow Child (Karasu no ko, 1959), about a dark-skinned mixed-race girl discriminated against in a Japanese slum, or like Kim the Shōnen of Death (Shinigami shōnen kimu, 1962-63), about a Korean-named boy in the American West who might actually be a living version of the earliest humans – these are a far cry from serious extrapolations of anthropology or paleontology. Still they do indicate that Shirato was reading widely on the subject of race and ethnogenesis. As for matrilineality, again it does not imply matriarchy and Nakane is careful to describe how Garo men are still very much in control and believe themselves superior to the women. But it is possible that Shirato, expressing grave doubts about abuses of patriarchal power repeatedly in his manga, found food for thought as well as fantasy in explications of social systems that differed from Japan’s own strongly father-and-son-centered one.

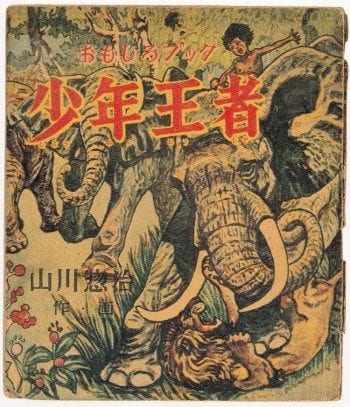

Nonetheless, if indeed Shirato read Nakane’s book, I suspect the real draw was the jungle sensationally advertised on its front wrapper. Many people pigeonhole Shirato as a Marxist. Certainly he committed many panels to speaking out against class oppression, as he did against racism and “caste” discrimination. But he also loved animal adventures. He thought highly enough of Ernest Thompson Seton’s tales about wolves, grizzlies, and other Northern American wildlife to adapt them into manga between 1961 and 1964. One of his first drawing jobs in the early 50s was as a copyist and colorist of kamishibai cards for Yamakawa Sōji’s mystery adventure The Bronze Devil (Seidō no majin) and his super popular Shōnen King (Shōnen ōja), about the Tarzan knock-off Shingo, son of a Japanese missionary and scientist, orphaned in the African jungle and adopted by a gorilla. The Yamakawa influence can be felt in many Shirato manga, especially the raised-by-beasts Wolf Boy (Ōkami kozō) from 1960-61, or even the ostensibly kōdan-grounded Sasuke (1961-66). He also did a manga adaptation of Yamakawa’s Shōnen King for a children’s magazine between 1961 and 1962, with terrific scenes of the half-naked Japanese boy Tarzan fighting hungry lions, haughty monster gorillas, and giant serpents in the African wilderness, with the help of his ape and elephant friends.

It is thus not hard to imagine Shirato turned on by Nakane’s opening description of the Assam jungle, as viewed from the window of her airplane, spreading out in “eerie black waves whose undulations get evermore violent.” Or mention that the area’s tribes were headhunters until recently. Or various anecdotes regarding leopards and rampaging elephants, like that advertised on the obi. Or, “At last it was time to leave, but it was hard to decide who was to lead the group. Everyone is afraid of the elephants. Finally a healthy and courageous-looking young man stepped forth, with the rest of us following behind, walking in a single-line on a mountain path that could hardly be called a path. . . . There are little houses built in the large trees close to the village, where travellers pass the night when it gets too late” – elephants rove mainly at night – “and where rocks are stockpiled so that, if an elephant comes out wandering looking for food amongst the crops, he can be driven off with stones.” And then a detail that the comic book artist of agricultural dramas would surely like: “Elephants love yams and sweet potatoes, the Garo’s main staples. They come to ravage the fields right around harvest time. One sometimes hear stories in the Garo Hills like that about a large herd coming and, in a single night, polishing off down to the root the year’s entire crop of food, causing famine and the total annihilation of a village.” It reminds me of Shirato’s Red Eyes (Akame, 1961-62), with its swarm of rabbits devouring fields, damning the farmers and their families to wither and die in the baking summer heat.

Officially for Nakane, the Assam region was “a treasure trove for the anthropologist, one of the rarest in the world.” Shirato was likewise interested in the idea of remote communities as repositories of vanishing human cultures, as the ethnographical depictions of the Northern Japanese matagi hunters at the beginning of The Legend of Kamuy (1964) show, or the same manga’s Ainu-speaking mountain ogre. Yet when it comes to the Garo chapters of Ninpō Hiwa, while there are a few panels that touch on rural Japanese folk toys and play, overall the series does not outwardly involve itself in ethnographical sources. There is, nonetheless, at least one potential iconographical link between the Iga interior and the jungle.

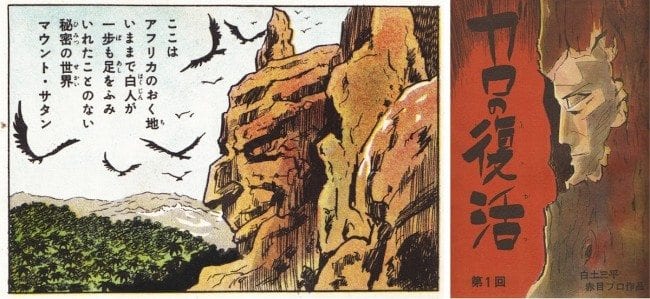

The title page of the first chapter of “The Revival of Garo” (Ninpō Hiwa, no. 15, January 1965) shows Garo’s face carved three-dimensionally into a tree. This the avuncular ninja does in the story in order to mark his territory. Three and a half years prior, in the first chapter of his adaptation of Shōnen King (August 1961), Shirato recycles the opening image of Yamakawa’s original emonogatari depicting “Mount Satan,” the face of which is shaped like a human face with a hooked nose. Its angular profile is like Garo’s in the tree.

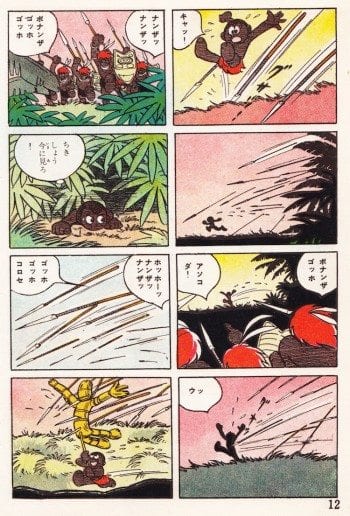

Or consider the name of the tribe that attacks future Tarzan boy Shingo’s family during his infancy, setting in motion the chain of reactions that put him at the teat of a gorilla. “All of sudden,” writes Yamakawa, “there was a bizarre scream of Oh oh, Ohhh oh, Oh oh nanza! Nanza! Dontata Dontata went the eerie sound of drums. They were being attacked by the Gara, a tribe of cannibals that live in the area. . . . Nanza! Dontata Dontata Dontata. Here come the Gara, with their poison arrows and throwing spears.” The savages abduct baby Shingo’s ward, the young and literate native Zanbaro, forcing him to live in solitary confinement for some fifteen years. One night, Zanbaro escapes captivity, fortuitously encounters the grown Shingo in his dead parent’s abandoned cabin, and teaches him how to read.

Gara. Zanbaro. Gara. Zanbaro. Zanbara. Garo? The jungle – the janGuru, that is – reverberates with strange katakana.

It requires but a small leap to get from Mount Satan and the cannibalistic Gara to Nakane’s Faces of Savagery, Faces of Civilization. The resonances between the two suggest an imaginative bridge between The Great Garo and the scintillating jungle – wherever on earth that jungle might be, Africa or India. That Shirato’s mind shuttled back and forth across this bridge is not surprising, considering mid-century Japanese juvenile entertainment and the artist’s interests and early career. Tales of adventure in exotic and hostile tropical lands had been extremely popular amongst Japanese boys since the beginning of the twentieth century and the rise of the Japanese Empire. While pulling widely from various foreign and domestic literary traditions, by the 1910s and 20s the model of British adventure fiction had become ascendant. Following the geographical footsteps of the British Empire, these Japanese stories are often set in India, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Abridged translations of Daniel Defoe, Robert Louis Stevenson, H. Rider Haggard, and Rudyard Kipling sold well. Hollywood adaptations of this and related material, as well as the arrival of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan in the 1920s, only further entrenched the spell of the predator and cannibal-infested jungle as the preferred location for heroic adventure. Local adaptations of this material abound in Japanese juvenile fiction, manga, and animation of the 1930s and early 40s. Most famous are Minami Yōichirō’s great hunt stories and Shimada Keizō’s cartoon emonogatari, The Adventurous Dankichi (1933-39). The imperial overtones and geographical locales of the British originals were easily translatable to Japan’s own Imperial undertakings in the South Pacific and Southeast Asia. The two powers, after all, fought over tropical territories during World War II, notably Singapore, Burma, and northeast India.

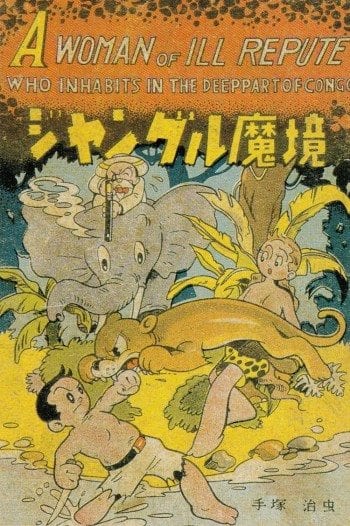

One might expect this genre to have vanished with the end of the war. But as demonstrated by Tezuka Osamu’s collaborative New Treasure Island (Shintakarajima, 1946-47), his many Haggard and Tarzan-inspired akahon, his Jungle Emperor (Janguru taitei, 1950-54), the popularity of Yamakawa’s Shōnen King, as well as Sugiura Shigeru’s many exotic-land adventures (some of this history I cover in my essay for the translation of Sugiura’s The Last of the Mohicans, from PictureBox) – the wellspring of Imperial fantasy continued to nourish Japanese manga well into the 1950s. The success of Nakane’s Faces of Savagery, with its cover promise of “beast-infested jungles” and “uncivilized tribes” suggests that these waters fed the non-fiction market as well.

Shirato’s work, in some ways, might be read as marking a final, revisionist stage in this history. When accounting for Shirato’s interest in the natural world, most studies emphasize his childhood in the Nagano countryside. When searching for the roots of his stories of the weak against the strong, they turn to his leftist background and sympathies for social pariah groups in Japan. However, as someone born in 1932, who was a fan and emulator of Tezuka’s akahon, and who began his professional career copying Yamakawa’s work, the influence of Japanese Imperial fantasies and their post-Imperial avatars should not be overlooked. Nor should the moralizing, character building idealism of Shōnen Club-variety boys fiction, kept alive and well in the postwar period by Yamakawa. “Such is the end of those who do nothing but evil,” says Shingo the jungle prince, standing over the trampled body of his archenemy, the lion. “There’s no lack of the strong in the world, but one must be strong in the right way. To protect the weak and pitiful of the world – it is for that that I will become strong."

Tellingly, the first issue of Garo, otherwise filled with ninja and samurai jidaigeki, contains “One Hundred Animal Tales” (“Dōbutsu hyakawa”) by Uchiyama Kanji, Ernest Thompson Seton’s Japanese translator. Set in Africa, it is wholly within the tradition of great hunt stories popularized by Minami Yōichirō in the 1930s. It was abandoned after three chapters, upon the commencement of The Legend of Kamuy. Shirato had other plans for his magazine. Its inclusion expresses Shirato’s debt to Uchiyama’s writing and translation work. But it also demonstrates that ninja, samurai, outcastes, and old school jungle adventures went together in Shirato’s head. As arbitrary as it might seem at first pass, there was thus a logic to naming such a magazine after a tribe of Mongoloid, elephant-combatting, matrilineal headhunters. Considering that The Legend of Kamuy marked an amplified commitment to exacting ethnographic and historical detail, there might have also been in the title of Garo an expression of homage to Nakane’s compelling mix of adventure, anthropology, and history.

Let me close with one last loose thread that potentially belongs to this tapestry. This is a topic I want to treat more fully in the future, so I will keep it sketchy here.

Shirato is usually thought of as an internationalist in terms of his class politics and a nationalist in terms of his cultural interests. But he was also interested in foreign folklore and myth, and one of his favorite sets of books seems to have been the Japanese translation of Phyllis Atkinson’s two-volume Best Short Stories of India (Bombay, 1931). The Japanese edition was abridged and published likewise as two-volumes in 1943, timed to coincide with the consolidation of Japan’s control of Burma and their preparation for the so-called “March on Delhi.” The translator was Shioya Tarō (1903-96), known in Japan for his translations of primarily German children’s stories and English-language SF novels. Curiously enough, he was also Shirato’s uncle, his mother’s elder brother. Thanks to the hard work of the Shirato Sanpei Graphic Literature site in Japan (Shirato Sanpei E Bungaku, probably the most extensive and reliable resource available on the artist’s work) we know that Shirato used Best Short Stories of India as source material on a number of occasions between the late 50s and 70s, earliest in Gold Pollen (Konjiki no kafun, 1958) and Two Year Sleepy Tarō (2-nen netarō, 1962-63). And while this has nothing to do with the ninja or the tribe directly, at the very least it allows one to say that Shirato was interested generally – very generally – in “that part of the world” prior to the naming of “Maha” Garo.

I know that the above adds up to little more than circumstantial evidence. But surely my hypothesis concerning the origins of the name Garo is more promising than the others out there. I will continue looking for fingerprints on this smoking gun.