Doug visited Japan in 1931 as part of his Asian tour for the documentary comic travelogue Around the World in 80 Minutes, released in 1933. After an initial stop for surfing and ukulele dancing in Hawaii, recounts Michael Scholten in his web article on this rarely-seen film, “the island hopping continued with a short visit to Japan and some travelogue clichés such as rickshaws, Mount Fuji, and autograph hunting Geishas. In Tokyo, Fairbanks had a brief reunion with Hollywood’s Asian-American actor and later The Bridge on the River Kwai-star Sessue Hayakawa, whose voice could not be heard during the very brief appearance. Instead, Fairbanks praised the good golf courses in Japan and their female caddies.” He continued on to China, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Cambodia, Siam, and India. Considering the media blitz around Chaplin and Babe Ruth’s visits to Japan in 1932 and 1934 respectively, I imagine Fairbanks’ jaunt too received attention in the local press. (The photo of him in Nikkō comes from this site about the Kanaya Hotel.)

Given The Mysterious Clover, the legacy of Fairbanks in Japan was clearly more than silly boot hats and newsreel footage. Whatever loss of speed and agility the actor himself had suffered, it was partially compensated for with the momentum provided by the memory of his early-mid 20s films. I have not done the research to state how common a feature Fairbanks was in Japanese youth publications of the 1920s. However, The Three Long Boots clearly treats him as a familiar friend, and considering the goopy obsession with American lifestyles and Hollywood glamour during those years in both boys’ and girls’ publications, I suspect that Fairbanks’ broad smile and mock-heroic stances graced Japanese youth venues with some frequency. I also suspect that his popularity, like Chaplin’s, bridged the gender divide. Though The Three Long Boots appeared in a boys’ magazine (Shōnen Club), Doug’s acrobatic litheness and the foreign historical romance of his films strikes me as the kind of attractions that would appeal particularly to girls. Matsumoto suggests as much with Clover. The manga was published a few years into the sound era and thus during Fairbanks slide into obscurity. But evidently the influence of his classic costume action films was still vibrant enough to inspire a new kind of shōjo hero and a new style of manga in The Mysterious Clover.

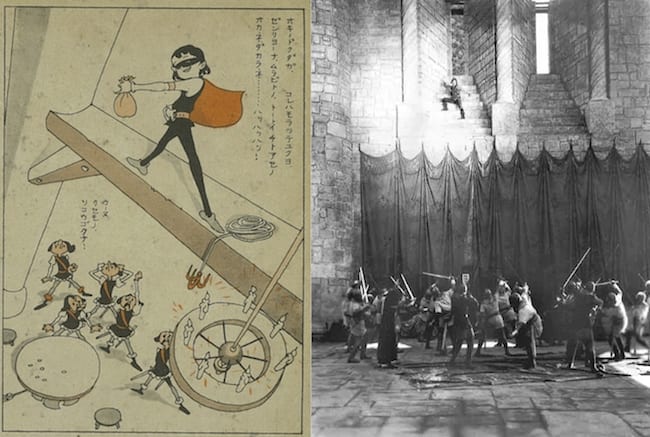

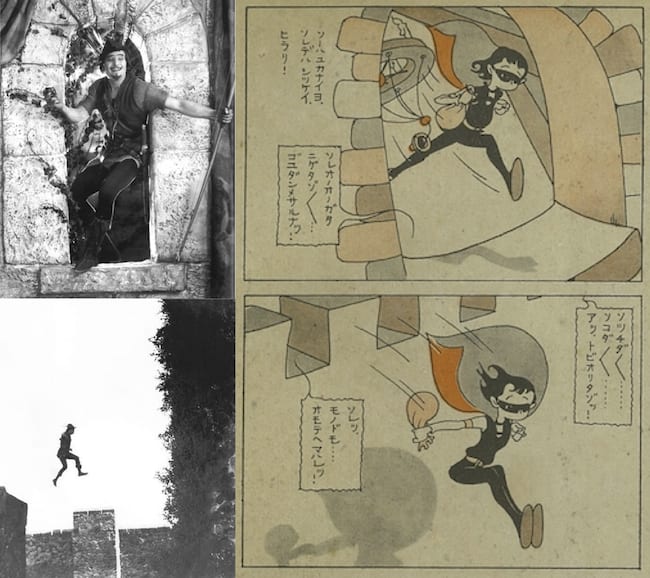

Clover’s body and physical movements seem to be modeled after Fairbanks. On the cover, she stands balletically with a rapier over her head, a far cry from the willowy bodies of jojōga illustration. She is a jolly jumper, bounding effortlessly over European medieval town walls. While perched on the rafters, she stands with typical Fairbanksian bravura – legs apart, hands on hips or belt, elbows sharply akimbo, head thrown back in laughter – good-spiritedly heckling her pursuers. She hides in haystacks, like Ahmed had in giant pots in The Thief of Bagdad (1924), popping out to makes fools of her enemies by knocking them in the head. “Windows were his only doors,” said Jean Epstein of Fairbanks. And one could say the same of Clover, bounding from rafter through window over wall to street. We never see her launch or land. We only see her fly.

Matsumoto’s appropriation of Fairbanks is particularly interesting from a social perspective. Yes, Clover is an early example of the European historical costume drama in shōjo manga, but note that the setting is primarily used as a means to allegorize moral character. Clover’s physical action, courage, and a strong sense of justice are foregrounded as positive character traits. Matsumoto was presumably drawing on contemporary shōnen fiction, in which such traits were common. Considering the Fairbanks factor, however, the inspiration is evidently mixed. Perhaps Matsumoto shared the opinion of Photoplay, which associated Fairbanks in the 20s with “the biff-bang Americanism for which we [Americans] are, justly and unjustly, renowned.” Such sentiments would have complemented Matsumoto’s affection for American spunkiness, outlined in my previous article on Matsumoto’s Kurumi-chan and her links to American “kawaii.” But given Clover’s age and righteousness, which make her more than a cute tomboy, presumably Matsumoto saw something deeper in Fairbanks.

Gaylyn Studlar argues in This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age (1996) that Fairbanks was the paradigmatic model of what boys should aspire to in post-Roosevelt America. Early in his movie career, according to Studlar, “Fairbanks became the unrivaled cinematic exponent of American good humor, preternatural optimism, and physical vitality.” Speaking of the actor’s young fans, “It was said they were diving off roofs and falling out of tree in unprecedented numbers in their attempt to emulate their cinematic hero.” Even well into middle age, he represented “boyish certainty in action.” “Fairbanks came to be regarded as a man in whom the primitive urges and instincts of boyhood had not died, but who reflected ideal masculine goodness in a manly way through physical regeneration and optimistic moral action. He became a cultural icon who evoked zealous commentary praising his youthfulness, his “spirit,” his “personality,” his amazing physicality – in short, his personification of everything little boys dreamed of becoming and everything men wished they might have retained of an idealized youth.” In 1924, the Boy Scouts reported, “He appeals to the eternal boy in us, the sun loving, swashbuckling, romantic boy in us. . . If he speaks to the mature, then think with what appeal he speaks to boys, to those youngsters of ours from whom the energy floods, as over a dam, seeking an outlet? The Douglas Fairbanks of the screen talks to them in a voice as authentic as their own.”

Significantly given Matsumoto’s shōjo appropriation, Fairbanks in his home context was touted as anti-feminine. The American boy culture of the 1910s and 20s for which he stood was defined by a cult of masculine character-building through physical exertion and wilderness exposure that was thought to guard against overly feminine influences at home and in white-collar cities. This was expressed not only in his films (most explicitly in his contemporary action comedies of the 1910s), but also in a handful of ghostwritten books. Against perceived threats of a country of moddycoddles, Fairbanks presented a model of what it meant to be a man: boyish, active, savage and instinctual in turns, yet at the same time constructively optimistic and with a strong sense of what is good and right. Studlar sees the costume dramas of the 1920s as an extension of this into the realm of historical fantasy. She views them as elaborations on the theme of rejuvenation through primitivism, formally set on the American frontier, now oriented toward further afar into history and foreign lands. “Finally, in the 1920s the star would beat a complete retreat to a fictional past. As the new decade got off to a roaring start, recapturing the romance of American’s lost boyhood seemed to require more extreme measures than the reconciliation of modernity and ‘Western fever.’” The adventure romances on which these costume extravaganzas were based, Studlar notes, were in many cases, like Robin Hood, the very stories that social reformers had promoted for the improvement of American boys.

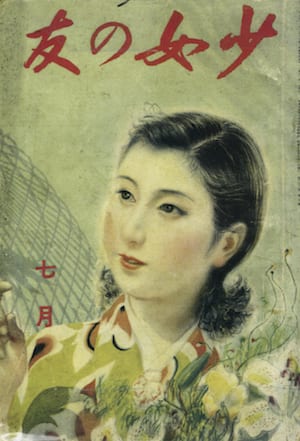

If this chivalrous schoolboy had appeared in a shōnen venue, an explanation would hardly be required. But what is a Fairbanks copycat doing in a shōjo magazine? Again, if it were his looks or his Hollywood glamour on display, one might understand. But it’s not: Clover recycles Fairbanks’ heroism and athleticism, but minus the handsome actor himself. This is particularly curious given the venue. Though not the girls’ magazine with the highest circulation (that was Kōdansha’s Shōjo Club), Shōjo no tomo was, according to Deborah Shamoon in her study of shōjo culture, Passionate Friendship (2012), “the magazine most closely associated with fostering the creation of girls’ culture and the one that inspired the most passionate devotion on the part of its readers.” Prewar shōjo magazines were, in general, aimed at urban, middle and upper class teenage girls, and more specifically “at girls attending single-sex secondary schools.” These magazines contributed, claims Shamoon, “to the construction of girls’ culture as a close, homosocial world.”

Some of this was engendered through reader-submitted stories, poems, and letters and the use of an esoteric English-peppered girls’ language of address and expression. Most important was the imagery of “passionate friendships and idealized ren’ai [Christian-inspired spiritual love] relationships that redirected girls’ sexual desire away from boys and kept them within the safe confines of the girls’ school.” Manga was not a dominant feature of shōjo magazines at this point. There are noticeably less manga in them than in their shōnen equivalents. Instead, illustrated fiction, poetry, educational essays, and reader letters and submissions dominated. Along with the Takarazuka Revue, writes Shamoon, these magazines “helped to develop the dominant aesthetics of girls’ culture: purity, elegance, innocence, and chastity.” They also ensconced the so-called “S relationship” – the romantic nonsexual “sister” relationship between younger and older girl friends – as a centerpiece of prewar shōjo culture.

In the previous overview of Matsumoto’s work, I cited artist Ueda Toshiko and scholar-curator Ueda Shizue, who have both pointed out that Matsumoto was aiming for something different from the usual run of shōjo imagery and characterization. The stereotypical features of prewar girls’ culture – same-sex relationships, wispy eroticism, sentimentality, longing, fragile beauty, urban chic, sports as a kind of fashion show, a fascination with Paris le mode – none of these define Clover. “This situation,” writes Natsume Fusanosuke, noting the same, “brings up interesting questions with regards to the relationship with girl readers. It is often said that prewar shōjo magazines, in contrast to the focus on risshin shusse [success in the world] in shōnen magazines, were focused on propagating the ideology of ryōsai kenbo [good wife, wise mother]. That might have been generally the case, but the girls depicted by Matsumoto take the initiative to act, solve problems, and transcend differences between male and female. It may be that this model never became mainstream because it was unpopular, yet it stands as an example for girls to take initiative.” Natsume cites Ueda’s Harbin-set Fuichin-san (1957-62) as an example of “tomboy heroes” that were inspired by Matsumoto’s example (Ueda was Matsumoto’s student). To this comparison, one should add two things. First, like Clover, Fuichin is a tomboy into adolescence, beyond the point which boyish behavior is typically thought of as natural and unthreatening in girls. Second, unlike Fuichin, Clover goes a step beyond boyish behavior by shedding recognizably feminine clothing.

What to make of this? One naturally thinks of the Takarazuka Revue, which at the time was still all-girl, whereas now it is made up of adult women. Takarazuka, as is well known, has been a central part of shōjo culture since the 1930s. However, Clover is not a Takarazuka type otokoyaku (male role). She might be a hero whose costume, physical movements, and behavior are inspired by male precedents, but there is no question of her gender. She is female. Though Takarazuka otokoyaku had, at the time, only recently begun cutting their hair and wearing wigs, they did tie their hair back or stuff it under their hats. Clover, meanwhile, lets her locks fly even when in costume. This begs a series of questions: Would Clover’s costume have been read as male in the 1930s? Would this have been seen at the time as an example of cross-dressing, as most scholars assume under the influence of Ribbon Knight? Or was Clover's costume androgynous and alien enough to be free of immediate gender associations? I cannot recall any Robin Hood boys’ manga from this period, though there are some during the Occupation. Could it be that Fairbanks’ prancing Robin Hood in tights made more sense as a female hero in prewar Japan? In Matsumoto’s prior illustration work, girls and young women are almost always in conventional feminine dress. Only in a few cases do they even wear slacks. His Walter Crane-inspired illustrations for Hans Christen Andersen stories always show girls in dresses, wraps, or other hanging garments. Still, could there have been in young woman’s fashion a place for this kind of get-up – if not as actual street wear, then perhaps as an androgynous ideal?

Rather than Takarazuka, I think the relevant comparison is between Clover and new models of Japanese womanhood. Matsumoto’s manga appears at the tail end of an important era in Japanese feminism. “It was at this time,” writes Barbara Sato about the mid 1910s in her book The New Japanese Woman (2003), “that the notorious ‘new woman’ (atarashii onna), a woman who transgressed social boundaries and questioned her dependence on men, started to pose a threat to gender relations.” In the 1920s, the decade in which American-type fashion, entertainment, and consumerism came to define Japanese modernism, and the decade in which Matsumoto became a contributing member to the visual culture of Japanese femininity, there were primarily three types of “new woman” circulating. According to Sato, these were “the bobbed-haired, short-skirted modern girl (modan gāru); the self-motivated housewife (shufu); and the rational, extroverted professional working woman (shokugyō fujin).” Of these three, Matsumoto, as an artist working for girls’ magazines, only had direct professional experience with representations of the first. Indeed, “modern girls” of various sorts (even a Chinese moga) do often appear in his manga and illustration work from the late 20s and early 30s. Yet while the moga suffered heavy criticism from both ends of the political spectrum – they were consumerist, sycophantic of French and American fashion, hedonistic and self-centered, promiscuous dress and behavior, obsession with the new in fashion and entertainment, disinterest in social change beyond those that impacted her private liberties – Matsumoto’s representations are decidedly unthreatening and sympathetic.

While scholars like Sato see the moga as a new and unconventional but ultimately conservative phenomenon – steering the gains of Meiji and Taishō era feminism into the relatively harmless arena of fashion and shopping – the late Miriam Silverberg has argued that this traditional view of the moga mistakes sensational representations in the mass media and entertainment for the real thing. The modern girl herself was instead at the avant-garde of “the history of working militant Japanese women.” Her breaking with norms of female modesty in both the sexual and consumer spheres coincided with the expansion of women’s legal rights in Japan as pertains to marriage, divorce, child custody, and property. This was also an era in which women became increasingly involved in professional organizations, as well as in social movements relating to labor, tenancy, and consumer rights. Not only did “modern girls” participate in these activities, says Silverberg, they also extended the fight into everyday life, into the streets, train cars, offices, and cafes of the city. While I am not convinced of the moga’s essential “militancy,” I think Silverberg’s take is valuable, in that it foregrounds what a sympathetic eye might see in, and imaginatively construct out of, the “modern girl” type, the facts of her living embodiment aside.

Clover is an ambivalent character in this regard. Given Matsumoto’s prior work, she presumably represents an elaboration of the modern girl. But her “militancy” can only be foregrounded in Matsumoto’s by simultaneously shedding her attachments to Ginza and Hollywood glitz. The role of “America” here is likewise complex. The moga was often referred to additionally as “Yankee girl.” This was not just for her mimicry of American fashion but her supposed appropriation of assertive female character types she saw on the silver screen: Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, Pola Negri. In a separate article, Deborah Shamoon has shown how the Hollywood actress helped shape a vision of the moga as “vamp.” But maybe a case could also be made that these actresses, mediated through the figure of the domestic moga and urged by changes in women’s rights and social roles, underwrote the rise of the tomboy in shōjo culture. It is indicative of the potential “American” connotations of these tropes that Matsumoto should shift from Pickford to Fairbanks (wife to husband, coincidentally), and from Jazz Age to Disney.

One might thus describe Matsumoto’s manga heroines (including Kurumi chan and Pepeko) as “post-modernist,” in the sense that they derive from the new types of femininity that emerged during the heyday of modanizumu in the 1920s, but without those features that were understood as morally and culturally problematic. Was Matsumoto trying to excavate the promises of the liberated and assertive New Woman from beneath the Modern Girl and the corrupting influences of American mass entertainment and consumerism amongst Japan’s urban middle class? If this is the case, it’s interesting that this “post-moga” coincides with Matsumoto’s rising interest in a Disney-inflected classicism, which I will describe in a future article. Disney had recently, around the same time in the mid 30s, rejected its roots in jazz age forms of lowbrow mass entertainment (think of the early Mickey movies) in the name of what was thought to be a more edifying European classicism (think of the color Silly Symphonies). Perhaps Matsumoto was working through something similar.

What did this mean in the context of the mid 30s? So far I have considered how Matsumoto was reforming models inherited from the recent past. How about looking ahead, to the expanding war? Could Clover, the charismatic and righteous avenger who is able to organize youth in battle, be a figure of things to come, things that were already set in motion by the Mukden Incident (1931) and Japan’s break with the League of Nations (1933)? After all, The Mysterious Clover was published in 1934, three years after the introduction of Norakuro (1931), and just one year after the commencement of The Adventuresome Dankichi (1933). Girls’ magazines also responded to the change in political climate, but when exactly and how?

Nakahara Jun’ichi’s removal from cover art duties in 1940 is usually seen as the iconic moment when Shōjo no tomo capitulated to militarism. Under pressure from the government’s censorship bureau, his bobbed and doe-eyed shōjo – which officials found “sickly and defeatist” – were replaced with no less pretty but certainly much plainer young girls rendered in the naturalistic style that is associated with the publications of the more conservative Kōdansha. Girl patriots began to proliferate in shōjo magazines. But according to Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase’s overview of wartime Shōjo no tomo (“Girls on the Homefront,” 2008), that active female type was figured largely in a supportive role, a cheerleader and sentimental inspiration for homesick male soldiers in battle. Scholars like Sandra Wilson, writing on patriotic women’s associations, report similar expectations upon adult women during the war. According to Silverberg, this era marked the demise of the modern girl, displaced by “a good wife and wise mother characterized by renewed ties of filiation to ‘tradition,’ state, and patriarchy.” “And although the Modern Girl reappeared after the war,” she adds, “she was by then reduced to a witless mannequin.”

But not so fast! The self-sufficient Clover is no wife or mother in training. She herself is the fighting soldier, not the tender solace behind the guns. She does not complement a primary masculinity, but rather usurps it. Were there other fictional heroines like this? It’ll have to be back to the archives for me to find out. Since those specific years – which follows the heyday of progressive modernism in the 1920s, but comes before the advent of full-scale war in China in 1937 – are often skipped over in English-language studies on Japanese girlhood and womanhood, I’ll probably have dig into Shōjo no tomo itself. What scholarship does exist on this period, doesn’t really fit Clover.

For example, in her study of Japanese beauty contests, Jennifer Robertson has shown how athletic female bodies were preferred in the 1930s. She sees this as an expression of contemporary thinking on eugenics. But before we race to call Katsuji fascist, it is important to remember that (though this is usually ignored in scholarship on the moga) the “modern girl” of the 20s was also known for engaging in male sports: swimming, rowing, skiing, equestrianism, golf, and ice skating, for example. Such imagery also appears in Matsumoto’s illustrations and his manga Pepeko and Chako (b. 1934), and there’s also the Fairbanks factor.

Similarly, art historian Asato Ikeda has shown that, within the very different world of neo-classical nihonga painting, there was a push by government ministers in the mid 30s to repress images of young women that were seen as overly liberal and hedonistic, opting instead for a classicizing “machine-ist” aesthetic, a “militarist moga” in accordance with Japanese totalitarian Gleichscaltung. For his Anglophilia and Disney tastes, Matsumoto’s own reformation of the moga moves in a very different direction.

Clover is really too much of a mixed bag to be slotted into a caricaturized ideological position. No doubt shōjo enthusiasts will celebrate her tomboyism, which serves in the story as an example to other girls to push aside sexist sissy boys and join the good fight. Though legible as a progressive promotion of assertive womanhood at a time when girls were being urged back into the mold of “good wife, wise mother,” it is less happily also a call for girls to act more like the ideal boys of shōnen fiction at a time when boys’ magazines were turning aggressively chauvinistic. Clover’s Robin Hood coupling of royalism and wealth redistribution makes her safely liberal, without being overly rightwing or left. The automatic, Pied Piper-like response of the entire youth population to the directives of a charismatic crusader might strike some as resonant with the imagery of wartime youth mobilization. But again, I think it would be unfair to the artist, to his longstanding commitment to promoting forms of progressive femininity within shōjo culture, and to his continuing fascination with “decadent” American culture, to call Clover proto-fascist. The manga was published in 1934, not 1937 or 1941. Things in Japan were going in a certain direction, but were not there yet. A liberal could still publicly be a liberal.

In closing, let’s not forget Fairbanks. If in fact it was Fairbanks’s historical romances that Matsumoto had in mind, it means that the actor’s contribution to comics culture is even greater than previously thought. As you know, he was one of the inspirations behind Superman. In the role of Zorro, he was also one of the models for Batman. The earliest male manga heroes with superhuman powers probably belong to the popular kōdan tradition of ninjas and exceptional samurai. As for Clover, the first Japanese female comic book superhero – or at least the first female manga masked avenger – her roots appear to be in the crossing of Hollywood and modern feminism. And considering the formal innovations of Clover, Fairbanks’ athleticism seems also to have inspired one of the first action-based manga whose illusion of movement was based, not on breakdowns and angles, but on dynamically moving bodies. The specifics of that I will discuss next time.

Here I close with a long quote from Richard Schickel. This is the opening paragraph of his book on Fairbanks, His Picture in the Papers (1973). Recalibrate the years, substitute names, and you get a decent description of the Mysterious Clover.

“To see him at work – even now, over thirty years after his premature death, a half-century, more or less, since he made his finest films – is to sense, as if for the first time, the full possibilities of a certain kind of movement in the movies. The stunts have been imitated and parodied, and so has been the screen personality, which was an improbable combination of the laughing cavalier and the dashing democrat. But no one has quite recaptured the freshness, the sense of perpetually innocent, perpetually adolescent narcissism, that Douglas Fairbanks brought to the screen. There was, of course, an element of the show-off in what he did, but it was (and still remains) deliciously palpable because he managed to communicate a feeling that he was as amazed and delighted as his audience by what that miraculous machine, his body, could accomplish when he launched it into the trajectory necessary to rescue the maiden fair, humiliate the villain, or escape the blundering soldiery that fruitlessly pursued him, in different uniforms but with consistent clumsiness, through at least a half-dozen pictures.”

Judging from the paean that began this essay, Matsumoto himself was an athletic do-gooder. Was Clover the result of Matsumoto seeing himself in Mr. Pep?

Postscript: A portion of the research and writing for this essay was supported by the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture.