Hi, and welcome back to TCJ. I'm going to be using this space to highlight new contributors to the website, in preview of the coming week.

Today we have a nice interview with Bryan Talbot, an artist I think you've all encountered at some point. My first experience with Talbot was via the 1992 Batman storyline "Mask" (from Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #39-40) - that's the one where a doctor tries to convince Bruce Wayne that he's just imagining himself as a superhero to escape the hell of his shitty life; my Pennsylvania brother, M. Night Shyamalan, used a pretty similar concept in his 2019 film Glass, while Scott Snyder & Greg Capullo did what registered to me as an homage at the top of their miniseries Batman: Last Knight on Earth. It was the first time I can remember reading a superhero comic made by somebody with no evident sympathy or nostalgia for superheroes at all. Of course, Talbot's best work-for-hire project remains 1989's Hellblazer Annual #1, with Jamie Delano & Dean Motter, one of those classic 'fuck the plot' issues that just enunciates occult riffs above the grit bath England of yesterday and today. Such was the promise of DC Comics Suggested for Mature Readers.

This week's interview is about Talbot's extensive recent work in creator-owned graphic novels. It is conducted by Tasha Lowe-Newsome, who works in film and journalism, including writing about comics - for example, she conducted the Journal's interview with Donna Barr in issue #190 of the print edition. She also wrote the 1992-94 Cult Press comic book series Raggedyman, which was drawn by Anthony Jon Hicks, and featured cover art by Mr. Bryan Talbot. We are very happy to welcome her back to TCJ.

Later this week, we will be seeing the TCJ debut of Lane Yates, a writer who has built a striking body of criticism at SOLRAD. Lane is also the creator of the fascinating webcomic Single Camera Sitcom, and the writer of several other small-press works. For TCJ, they will be presenting a reflective essay on Tom King, who is one of the very popular superhero comic book writers of today - the type you see mentioned in media outlets that don't often cover comic books as proof that superhero comics are good. It's about really getting in to a writer's work, and then really kind of getting out of their work, while still buying and reading all of it; along the way, we learn the true allegiances of the superhero industrial complex.

Plus, great stuff by returning contributors! Merriment every day! Please look forward to it!

* * *

The two of them were actually in a new comic very recently: Last Gasp's Slow Death Zero, edited by Jon B. Cooke & Ronald E. Turner, and published just a few months ago. It's a bookshelf-ready revival of the old Slow Death Funnies (est. 1970), in which underground cartoonists published ecologically-themed short comics; the new one has one of the last new comics drawn by Richard Corben, plus pieces by alt-era cartoonists like Peter Bagge and Rick Altergott. Talbot was part of the original run of Slow Death, I believe in the late-coming final issue (#11, 1992), as was the writer Tom Veitch, Rick's brother, although I think this is Rick Veitch's first appearance on the title. Reading their new pieces, Veitch's and Talbot's, I was struck by how the two shorts illustrate the differences in perspective between these two storytellers. [EDIT: Actually, Talbot's piece is not new; see the comments below.]

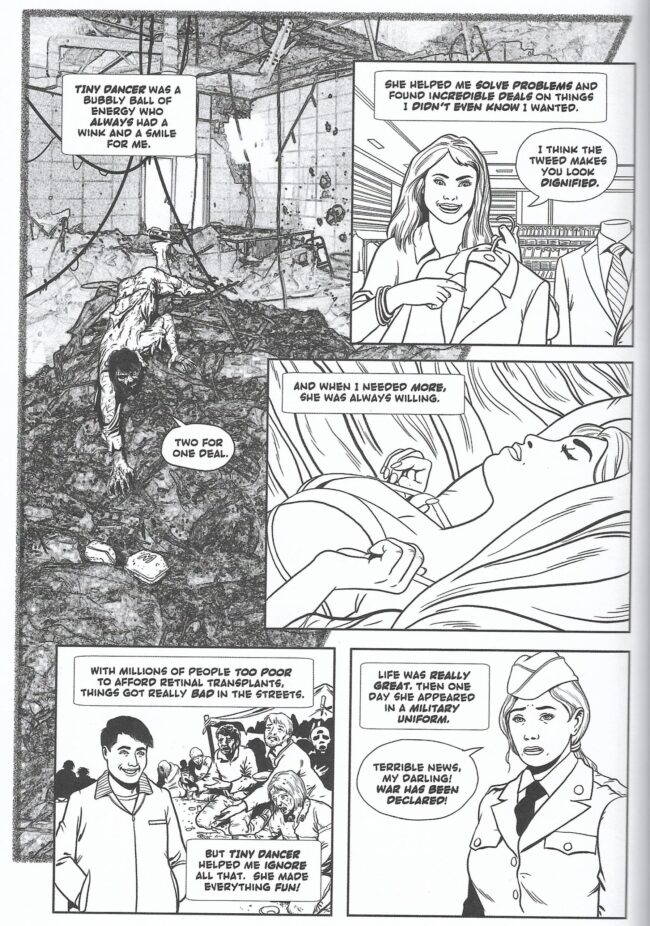

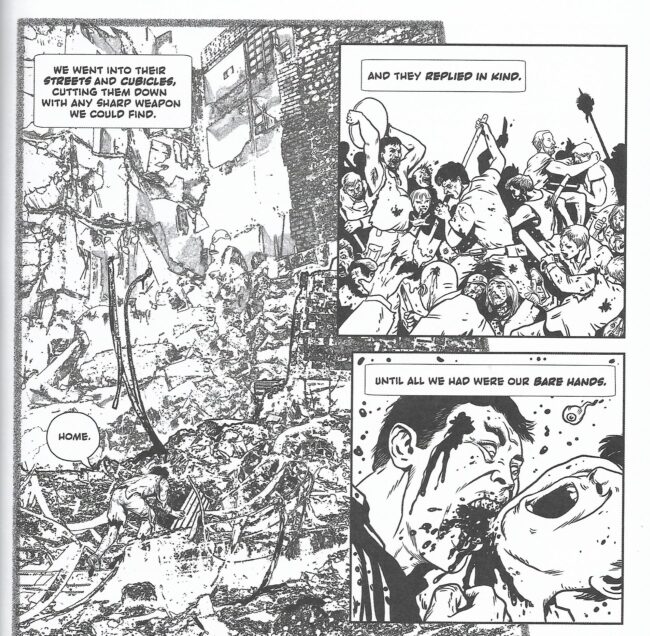

This is from Veitch's story, "Tiny Dancer" - the pages are all set up so that there is a large 'low-res' background image set in a destroyed environment with sharper, smaller panels set on top, in the manner of augmented reality experiences. It's the future (just barely), and those with adequate employer-provided insurance coverage have gotten retinal surgery that superimposes a beautiful 'mind-mate' companion onto everything they see. These digital assistants provide companionship, sexual gratification, and great deals on local shopping - it's a little bit Siri/Alexa, a little bit the film Her, but the economics and mass-production evident in Veitch's story reminded me a lot of the lucrative world of gacha games, where the player's addictive tendencies are stokes so that they keep hitting the Spend Real Money button on their phone for chances at winning the rarest (and cutest!) characters to use in the game. Veitch's protagonist eventually marries his mind-mate, which analogizes to the intensity some gamers feel toward characters and rosters into which they've poured much time and cash.

Of course, such valuable entertainment also functions as a platform for nationalist and martial tendencies; that last panel above is *so* funny to me - a new skin signaling the dawn of the waifu proxy war.

This is a subject matter that greatly appeals to the childless editor of a comic book website. The central joke of Veitch's comic -- the structural joke -- is that the advertising-mandated existence of the mind-made endures a ways past everything else, inviting you to treat yourself to a restaurant in the midst of rubble. I recall the strange, paralyzed state of commercials online as COVID really broke loose in the States, and I think Veitch's vision of the end is unusually prescient.

Then, Talbot:

Hell yeah, full-color thrill-power. "Memento" is a wordless story (save for a Crypt-Keeper-like intro by a cartoon Ron Turner, which also kind of messes up the visual conceit of Veitch's piece) about a hired gun blasting through a hellish underground society to deliver a special item to a client in the devastated surface world. Talbot really leans into his talent for grotesquerie, which is another trait he shares with Veitch, although I think the studied subject matter of his more recent books (and the gleaming digital façade of his Grandville anthropomorphic animal comics) gives less need for this tool in the kit.

It does make me think. Probably, I am physically closest to the guy at the bottom left of the above page, who is uncomfortably consuming things in the midst of a terrible orgy, away from the suffering of the world. Talbot's hero, meanwhile, is fit and skilled, and utterly composed. They are strong, which is something that comes up often in Talbot's work. In his Batman story, "Mask", there is a sort of Schrödinger's cat type of ending, where Batman is presented with a door that represents the weak Bruce Wayne and the strong Batman. Naturally, Batman chooses the Batman door, and he is therefore real, and Bruce Wayne is not. But - Bruce Wayne, weak and sick, is still real; we just can't see him anymore, because he did not occur, because his life cannot really exist in a corporate-owned superhero comic. Similarly, Talbot's own characters navigate the contours of power. Luther Arkwright is very powerful; LeBrock, the main character of Grandville, is a strapping and inquisitive badger. The various heroines of Talbot's collaborations with the writer Mary M. Talbot stand astride great historical moments, or encounter extraordinary personalities, or are extraordinary personalities. These are not perfect, or uncomplicated characters, but they move through their worlds with purpose, like the "Memento" hero.

Veitch, I think, presents people as much more fallible, susceptible to temptation, or fundamentally malleable. His many dream comics, lucid as the dreamer may be, force a vulnerability on Roarin' Rick, who cannot entirely control what is coming. The sidekicks of Brat Pack are seduced and exploited; the comics industry figures in The Maximortal subject to rips in history, as the all-powerful hero at the center melts and rips bodies, descending like a glowing terror, Jack Chick's God, archetypical yet not entirely unknowable. I think this is the fundamental and hopefully-illustrative difference between these two artists I associate so much with each other - Veitch floating inside the body and mind of history, and Talbot urging us to be strong and studied.

* * *

Anyway, thank you for continuing to enjoy the blog's gradual transformation into Rorschach's journal. I'll be back in this space next week, unless I die.