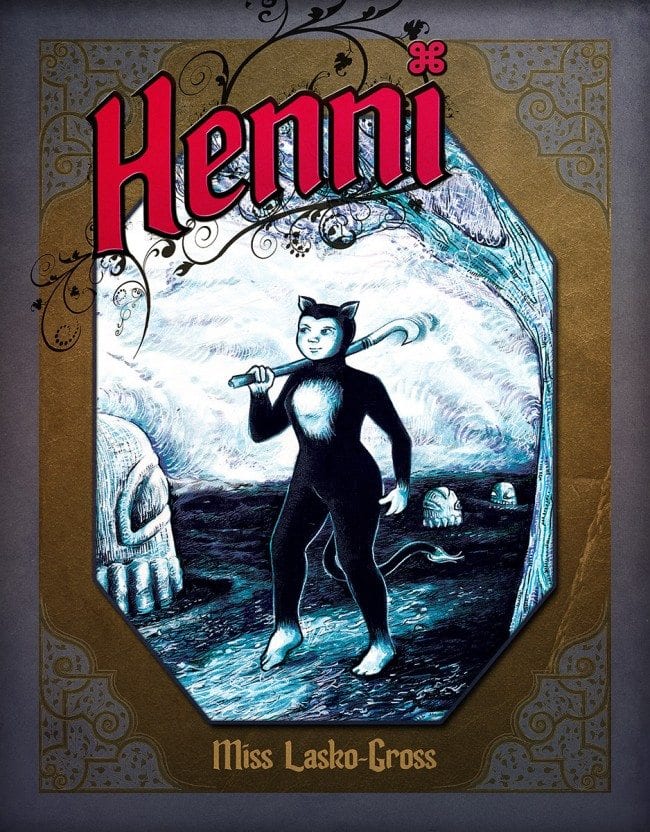

Miss Lasko-Gross has published three books, two of autobiographical comics published by Fantagraphics, and a third book, Miss Lasko-Gross 1994-2014, which is published digitally by Dyclops and available through Comixology. Her new book, Henni, is out now from Z2 Comics and is a departure in many respects from her previous books. Henni is the story of a young girl cat who leaves her repressive village. It’s an allegorical tale, but shares the thematic concerns of her earlier books. We spoke recently about why she wanted to make such a different project, her plan to depict her life in comics and more.

Miss Lasko-Gross has published three books, two of autobiographical comics published by Fantagraphics, and a third book, Miss Lasko-Gross 1994-2014, which is published digitally by Dyclops and available through Comixology. Her new book, Henni, is out now from Z2 Comics and is a departure in many respects from her previous books. Henni is the story of a young girl cat who leaves her repressive village. It’s an allegorical tale, but shares the thematic concerns of her earlier books. We spoke recently about why she wanted to make such a different project, her plan to depict her life in comics and more.

How do you describe Henni?

The adventures of a dangerously curious young girl/cat, who's desire for truth exposes some truly unsavory secrets. Henni is forced to flee her insular village to avoid death by stoning and venture out into an unknown and hostile world. It's a bit of a fairy tale as well as an allegory about the dangers of fundamentalism.

I was inspired by Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs and Steel to consider what life would be like in a world with an extreme paucity of natural resources. What direction would social evolution take with no domesticated animals, extremely limited metal and communication options. It's a very post modern fantasy, instead of adding magical or romantic elements, I've subtracted many of the casual miracles which have driven our history.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

I was working on a pretty grim piece of non-fiction–about a friend of mine who was injured in an explosion–and started Henni as a side project for the House of Twelve Comixology app. I had only meant to do the bare minimum for the app, but as I worked the story began flowing and expanding into a complete book.

Graphic novels take years to complete, and there isn't much sustainable money in it, so there's really no reason to labor on anything you're not passionate about. Henni is the kind of story I've always loved as a reader, kinetic, strange and full of juicy little surprises. So, basically, I abandoned the other project and threw myself into Henni with no regrets.

Did you have a model for what you were trying to do with Henni?

Did you have a model for what you were trying to do with Henni?

I think I've drawn on my childhood love of Greek mythology, Aesop's fables and Grimms' fairy tales–minus the elements of fate, justice and inevitability. Also, hopefully, exploring some touchy philosophical concepts in an artistic and non-didactic way.

I really like the phrase you used to describe the book, “postmodern fantasy.” This is something that’s become much more commonplace in recent years. What interested you in that approach?

Regardless of setting, there's a certain amount of skepticism and self-awareness that belongs in the mind of all characters–even ones as naive as a younger Henni is. Beautiful classic fairy tales already exist in abundance and plenty of "modern" ones are being churned out, wherein the fact that a female protagonist is the one committing the heroic violence is seen as progressive. I want to occupy the gulf between the classic hero quest and the horrible ambiguous truth of existence.

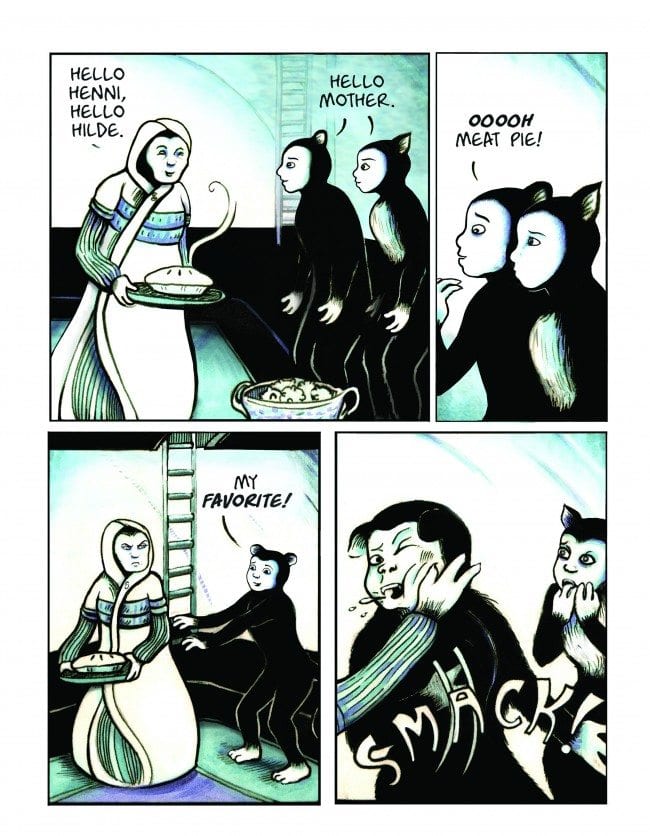

In discussions I've had with readers, the characters of Mother and the Templemen have been described as "evil." presumably because, in the context of more classic tales they would be by default. They behave meanly and get in the way of the protagonists interests and therefore are the "bad guys." However, in this approach, they're written as people who–in the case of the Templemen–will do anything to preserve their privileged position, which they "deserve" as guardians of the good/correct social order. Behind closed doors they joke in a cavalier manner about truths only they (the ruling elite) can comprehend. But while the Templemen may have contempt for the common man, their ultimate intent is to maintain the group cohesion of the village–albeit in a way that's most advantageous to themselves.

Henni's Mother also sees herself as a guardian of righteousness, though from an outsider’s perspective, she's a physically and verbally abusive parent. She clearly loves her daughters and has done everything in her power to protect them from what she sees as the corrosive influence of their angry intellectual father Hedrik.

I'd compare my interest in this style of writing to the fact that I find it more exciting to go for a walk outdoors than to ride a roller coaster. The risk of anything or nothing happening vs. a regulated industrial "thrill ride."

There are odd fantastic elements in the story. World building, at least on this scale, isn’t something that you’ve done before. Was that a big challenge?

There are odd fantastic elements in the story. World building, at least on this scale, isn’t something that you’ve done before. Was that a big challenge?

It has its own set of freedoms and limitations. The weirder and more alien you want to go with the drawing, the more forethought you need regarding functionality and believability. Henni opens with a series of panels containing ancient ruins that are, to the human eye, proportioned in a logical and recognizable way. The landscape is wide open and uncultivated. Within the imposing–and apparently unnecessary–gates of Henni's village, disruptive architectural nonsense takes over.

I guess the big challenge is balancing the creative fun of world building with visual choices that serve and reinforce the the plot. Within the "nonsense" is a village intentionally designed at an odd scale with strangely placed divisions, suggesting–subtly–the fact that it's intentionally cramped, claustrophobic and without privacy.

I have to ask, why cats?

Non-human characters create an extra layer of detachment so readers can enjoy the book as it's intended. That is, without feeling compelled to assign every character an earthly cultural equivalent. Every group of "people" depicted are a combination of influences, intended to be familiar but unplaceable. Henni's village, for example, has touches of Scandinavia, Medieval Europe and pre-Colombian South America. The last thing I want as a writer, is for someone to put up a wall of defensiveness because they feel their own beliefs are being attacked or ridiculed.

How was it different working on this book than on your autobiographical work? Did it require a completely different approach?

How was it different working on this book than on your autobiographical work? Did it require a completely different approach?

Autobio is more of a reductive process. The big decisions involve what to edit out and what to reveal. It's largely a matter of economy and focus, as there isn't room for an entire life unless you are hoping to make the dullest, most self-indulgent graphic novel ever.

Fiction is more about creating structure and world building. Deciding, as the god of your own tiny universe, where the boundaries are that keep it interesting and internally consistent. The truth of a personal life is fixed (though somewhat subjective) so moving into fiction affords me the freedom to use non-human fantasy characters such as the Disruptor, (a sculptor who's sacrificed her eyes for art) benevolent old brainwashers and delicious Baked Goods with a sinister life determining purpose.

This is a question I probably would have asked earlier if it weren’t for the nature of your first two books, but I’m curious, how autobiographical do you think Henni is?

Although everyone faces their own personal struggle, realistically I belong to the luckiest group of humans in all of recorded history. I've never been without enough to eat, a home, a family, basic human rights or educational opportunity. Henni, on the other hand, is the product of deprivation. After her father is "disposed of," she's denied all access to education and enters into an emotional/intellectual exile. Surrounded by those who are ostensibly "her people," she's disliked and mistrusted. Even in private conversation, her friends and family are completely unwilling to challenge the value of the repressive culture in which they live.

I'd like to think that, facing similar circumstances, I could be as brave and trusting as she is. Her clarity in the face of danger and canny verbal restraint toward monstrous assholes, are qualities I do NOT possess. The inability to keep my mouth shut in the face of perceived injustice has led me into some truly ill-advised arguments with Law Enforcement–who don't as a rule enjoy criticism of their take on civil liberties–and dangerously disturbed individuals.

I guess I'm just curious about whether you see your books as sharing the same sensibility or how closely related you think of them.

Though superficially very different works, I think the values and worldview do converge quite a bit. There are certainly common themes of Feminism, and independent thought vs. mindless submission to authority throughout.

You said that the experience was very different for you than making autobio work, but it does seem to come from the same impulse, or at least many of the same ideas and concerns animate your fiction and nonfiction.

You said that the experience was very different for you than making autobio work, but it does seem to come from the same impulse, or at least many of the same ideas and concerns animate your fiction and nonfiction.

Stripped to the bones, all three are very much about taking control of your own existence and reframing how you view the reality of your circumstances. Henni Book 2–which I'm about 170 pages into drawing–also parallels A Mess Of Everything in considering how to deal with your overwhelming lack of significance and power in an unfair world. As well as learning to recognize and seize the opportunities you do have. And all four books certainly express skepticism towards anyone offering to do your thinking for you.

How did you end up connecting with Z2 Comics?

Josh Frankel (Z2) had seen an early iteration of Henni. We discussed the work in progress for awhile when I wasn't sure where it would be a good fit. Right away he got the story and appreciated it's potential. Also, having the amazing Emmy winning designer Jim Pascoe attached didn't hurt.

When A Mess of Everything was released, it was described as the second book of a trilogy. Is your plan still to make an autobiographical trilogy?

I get asked about that quite a bit. The first two books–Escape From “Special” and A Mess of Everything–were very fun, agonizing and cathartic to create. And while I've never been crazy about the idea of a trilogy, it's always been an ambition of mine to document an entire lifetime in comics. I think I'd like to be out of my thirties before having the distance and perspective to summarize my twenties. Also, as I often say, there's only so many times you can draw your own stupid face before needing a break.

Doing a third book immediately after the first two would have been a very easy–but disingenuous–career choice. When I'm in the right head space and it feels organic and unforced I'll do it.

In other words you never thought of the autobiographical books as a trilogy. Each book represents a particular moment in time?

Yes, each one represents a stage of life. Escape From "Special" was about childhood, starting from the earliest flashes of memory I have. A Mess Of Everything focuses on my teens, the stories are longer and contain more context which wasn't a stylistic choice but a function of how memories are organized.

Where did this idea of documenting your life in comics come from?

It's something I've been kicking around for awhile. The most important part isn't that it's specifically my life as much as "a cartoonist’s entire output." From some of the earliest drawings–like those I recreated in Escape from "Special"–through their creative peak into the inevitable decline with extremely old age. All of this physically present in the art itself and not just the material of the stories.

You mentioned that you’re working on Henni Book 2. Is there anything you can say–or want to say–about what people can look forward to in it?

In the context of the larger world, more about Henni is revealed. Once she's navigated the falls it becomes clear just how geographically and culturally isolated the Northern lands really were. Through the eyes of a stranger she see's herself for the first time as having a race a class and a culture. All of which are unwelcome baggage as her adventures and troubles continue.