Interviews are typically peppered with ums and uhs, the fillers and hesitations that characterize extemporaneous speech. There are also the false starts, thoughts begun but never brought to fruition. A conversation with Jim Woodring contains none of these. He speaks with a calm assurance, even when delving into the more troubling aspects of his life (such as the alcoholism of his twenties and the unsettling, often terrifying visions that began in childhood and have continued into adulthood), and answers questions about the practical and spiritual aspects of his work with equal regard.

Woodring’s eloquence might seem at odds with the nature of his work—with the exception of Jim, a collection of his early dream comics, he creates nearly wordless tales—but his Frank stories are meticulously expressive, relying on the actions of a small, steadfast group of characters to articulate what words cannot.

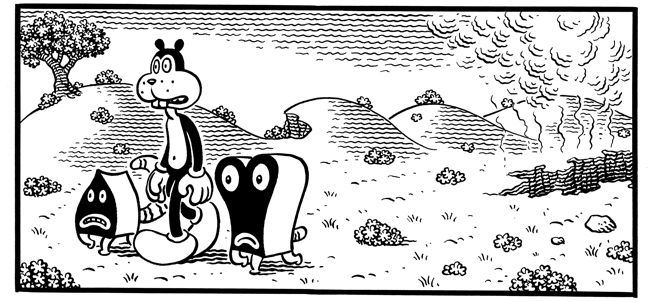

Last year, Woodring published his first book-length work, Weathercraft (for which he received The Stranger’s Genius Award in Literature); this month, he released his second, Congress of the Animals. The two volumes read, in some ways, like extended versions of his earlier stories, but in fact the world of Frank, Pupshaw, Manhog, and Whim has expanded, introducing uniquely weird new realms in the Unifactor and more complex, arresting exploits.

RUDICK: Weathercraft was your first long-form work. Have you enjoyed writing Frank on that larger scale?

WOODRING: Well, I enjoy drawing the Frank comics under any circumstances. I guess I’m more pleased to have a long work because it’s more of an achievement. But it’s a lot more difficult to do a long-form story than a short one.

RUDICK: In what ways is it more difficult?

WOODRING: It’s harder to sustain a story over that long period of time. The same problems that any kind of writer trying a long story experiences, and doing it in such a way that it maintains people’s interest throughout, pertain here. You have to make sure it doesn’t drag and that people don’t run out of enthusiasm in the middle, and that the structure holds up, and that when they reach the end they feel like they’ve been through something that was worthwhile. It’s much easier to get all of those effects in an experience that’s over quickly.

RUDICK: Does it require more thought before beginning, more preparation?

WOODRING: There’s a lot more preparation that goes into it, because a lot more things have to be developed and figured out. There are so many more aspects to a long story. They have to be developed in such a way that they work together and contribute to a cohesive whole. So it does take more planning to do a single hundred-page story than it does four twenty-page stories.

RUDICK: Do you think you achieved all of these things in Weathercraft?

WOODRING: As far as I’m concerned I did, but it’s not really for me to say. The story must seem ambiguous to some people. I know that some people get it in the way I intended it. I know other people get things out of it that I didn’t intend to put in there, which is always the way with these stories. But as far as I’m concerned, yes, with Weathercraft and Congress of the Animals I did what I set out to do.

RUDICK: Was it easier making Congress of the Animals after you had already done Weathercraft?

WOODRING: No, because it was a more personal and more difficult story to tell. It’s less oblique than Weathercraft. I think there’s more packed into it, and it was difficult to edit down the sequences to the length that was allotted to them by the hundred pages. Also, it was a rough year. I had a good friend who went through a painful final decline that year, and there were some other unpleasant distractions as well. I don’t have a lot of happy memories of the year I spent working on that thing.

RUDICK: In what way is it more personal?

RUDICK: In what way is it more personal?

WOODRING: A lot of the incidents in it have parallels to my life. The things in Weathercraft are things that have meaning for me, things I’ve either experienced or hope to experience, or distorted versions of things I think other people have experienced. The trajectory of Congress of the Animals related to events in my life in a more personal way.

RUDICK: Did you set out to make it more personal, or is that the way it developed?

WOODRING: I had the story before I knew I was going to do it as a hundred-page comic, and those Frank stories kind of write themselves. I set out to gather material for them and when I have enough of it, and it’s the right kind of stuff that fits together in such a way, it makes a whole that works. So I didn’t really set out to write Congress of the Animals as a personal story, but once I had the story in hand and I realized that it was that personal—I had that in mind all the time I was drawing it and that influenced some of the visuals, the factory, for example, and the faceless men.

RUDICK: How long did it take for the story to come together in your mind?

WOODRING: The initial story came very quickly. The working out of it—drawing it up, laying it out, making the page breaks, and putting it all to business—took about two weeks.

RUDICK: Did the events of that year go into the story?

WOODRING: Not directly. I drew a large part of the first chunk during a month I spent up in Homer, Alaska. Being there affected my mood strongly, and that affected the work. I can see it in the finished product, although I’m not sure anybody else could. The section where Frank finds himself among the faceless, gut-worshiping men came out differently than I originally intended because I was drawing it at the same time that my friend was embarking upon his miserable death. I actually softened that sequence up quite a bit out of tender feelings for my friend. There was stuff I had put in the original structure of that sequence that was more disturbing than what appeared in the book. I guess I was just feeling overwhelmed by negativity, and I thought, You know, I don’t have to rub people’s noses in this quite to this extent. I think I’ll just back off a bit.

RUDICK: Do you usually go back and edit your work in that way?

WOODRING: No. Usually, once I’ve got it all planned out, I stick to the plan. Sometimes I’ll make changes because I’ll realize that there’s a redundancy or a bottleneck or some flow problem, so I’ll make a change to it after that. Sometimes I’ll draw a page or two, and I just won’t like the way it came out or I’ll see a way I can make it better, so I’ll redraw it. I don’t make any big changes really, just little adjustments of tone and technique. I stick to the plan pretty well because the story I want to tell exists as a story. It’s not arbitrary. I can’t just swap something out and put in something else that’s weird. It won’t work. But I can always cut back.

RUDICK: What prompted your change from doing stories to doing a book-length tale?

WOODRING: For one thing, the nature of the comic-book industry changed. When I first started doing comics, comics is what they were—thirty-two-page pamphlets. Then they were sometimes collected into softcover books. Those collections were always seen as being a bit illegitimate, because the comics were fetish items, and the collections didn’t have that quality. Then sometime during the ’90s—partly because it became less expensive to do color printing and specialty printing and embossed covers and foil covers and metallic inks and all the other things publishers would not have considered doing before because they were prohibitively expensive—people started doing books that could be published as hardcovers with dust jackets and $24 price tags. That became an accepted format, and that was something I wanted to do.

RUDICK: How did you go from writing the autobiographical Jim to writing the Frank stories?

WOODRING: In the early ’90s, there was a fellow named Mark Landman who had an anthology magazine called Buzz that I’d contributed some things to. He called me up one day and said, “I think it’d be good if you did a comic strip that looked like a normal comic but wasn’t.” And I’d already developed the Frank character and the Manhog character, and I thought, You know, that would be a fun thing to do. So I drew a Frank three-pager that, apart from a few stylistic differences, had everything in place that all the comics have had since. So it was really that magic phrase “do a comic that looks normal, but isn’t,” suggested by Mark Landman, that put me on that track.

RUDICK: Did you have some sense at the time of the world the characters would inhabit?

WOODRING: It’s pretty much all there in the very first story.

RUDICK: And the first story was wordless.

WOODRING: Yes, they’re all wordless, or almost.

RUDICK: Why wordless?

WOODRING: Because I wanted to do a story that expressed things that were difficult to express in words. I wanted the stories to be beyond time and place. And I knew that if I had these characters speaking, they’d be speaking in idiomatic modern English, which would tie it to this time and place. I wanted it to be specific in terms of what was going on but unspecific in terms of how those events could be interpreted. I just thought it’d be more powerful and ambiguous and genuine. Words can be deceptive—you start using words and people apply to them whatever meanings their prejudices dictate. Images are less open to interpretation in a way.

RUDICK: Do you hope that your stories have a universal quality?

WOODRING: Yes, I hope they do. I intend for them to.

RUDICK: How do you think about sound in a wordless drawing and how do you manifest it?

WOODRING: Sometimes I’ll start a story with a sunrise. In fact, I would always like to start a story with a sunrise. It seems like a good place to start, nice and fresh. I like the sounds that accompany a sunrise: the birds start singing before the sun comes up, as the world comes to life all the noises begin, and you don’t hear a lot of sounds that aren’t natural. When I look at the Frank comics and think about that world, I hear a lot of chirping and buzzing and wind and natural sounds. I can hear in my head the noises that Frank makes and that Pupshaw makes and that Manhog makes—Manhog’s noises are not hard to imagine. I imagine Pupshaw growling and humming and purring, making little affirmative noises. Frank making little quizzical ones. So, I can imagine the sounds for it very readily.

RUDICK: Do you rely on dreams and the experiences of your childhood to create the stories?

WOODRING: Not for the Frank stories. I use that stuff a lot in Jim and for a story that I’m working on now—it’s a literal retelling of a dream. The Frank stories are just pulled out of the ether. When I sit down to do a Frank story, I’ve got no preconception, no sense of where I want to go with it. They just materialize out of thin air.

RUDICK: Do you draw everyday?

WOODRING: Yes.

RUDICK: How often do the stories come to you?

WOODRING: The germs of stories come to me frequently. I have these little sketchbooks I fill up, one per month. I also have other ones I fill up less frequently that are full of words and ideas. They’re full of single-sentence synopses of stories that could be developed.

RUDICK: You said the stories are full in your mind before you begin, but do you ever begin drawing and have it come apart?

RUDICK: You said the stories are full in your mind before you begin, but do you ever begin drawing and have it come apart?

WOODRING: Not during the finished drawing. By the time I’m doing the finished drawing, I have it all sketched out and planned out, and I know what the shape of it is going to be and what it’s going to do, even if I don’t have a full understanding of what it means. By the time I sit down to do the final drawing on a story, I always see it through to the end. I’ve begun to sketch out a lot of stories that went nowhere, because I realized that what looked like a solid structure was not, so I abandon them. Sometimes I come back to them and more inspiration comes, and probably more often than that I just leave them hanging, floating around out there like fragments.

RUDICK: Nearly twenty years ago, you described your work as “a collection of mistakes strung together.” Do you still feel that way?

WOODRING: No. I was really sort of new to cartooning back then and feeling my way through it. I didn’t have the control or the understanding that I have now. I’ve gotten better since then.

RUDICK: Do you like your work now?

WOODRING: Yeah, but you know I’ve always liked my work, which is a good thing because some people really don’t like it, and if I were ambivalent about it myself it would be terrible. I hear people say that my work makes them sick. Well, sometimes it makes me sick, too, but I can find qualities in it that I like. It reflects the world back to me in a reductive way that I ultimately enjoy. What I put into my work are the things I like to see and think about and experience.

RUDICK: Do you get a lot of those kinds of criticisms?

WOODRING: Not a lot. But the people who don’t like my work really, really hate it. I’ve heard from more than one person who has said that it made them feel physically sick. It wasn’t just the stuff I draw that is overtly creepy. Some vibrating quality in my work, some underlying tone to it, really rubs some people the wrong way. I guess that’s kind of a backhanded compliment—that it has strength to do that even when it’s innocuous. So I don’t mind.

RUDICK: What is it about your work that makes them so ill?

WOODRING: I don’t know. I’d like to think that they’re just petty and jealous. But that’s probably not it. I really don’t know what it is. It seems positive to me. I like it. You know, I’ve heard people say, I can’t stand Duke Ellington or I can’t stand The Beatles or I just can’t listen to Mozart, it makes me seasick, and I can’t understand that at all. I’m not in any way putting myself in those categories, but I am saying that it’s as incomprehensible to me when people don’t like my work.

(continued)