LEES: Yeah. So, after Strange Weather Lately came out, you had a couple of collected editions, and then you began working on Louis. Now, you said that the idea for that come from a concept, I think you came up with, Sandra, about a character trapped in a cell. The idea itself seemed to be very reminiscent, well certainly the ideas were very reminiscent, of The Maze, and Strange Weather Lately, but the way you rendered it was completely contrary. It’s very approachable, it’s very light, it’s very colorful; it looks like a children’s book. Was this supposed to be a deliberate deception or contradiction?

MARRS: First of all, when we finished Strange Weather Lately, we were conscious that we wanted to work on something much lighter, because working on something dark all the time was starting to bring me down a bit, I guess. So, we wanted to kind of shift our work.

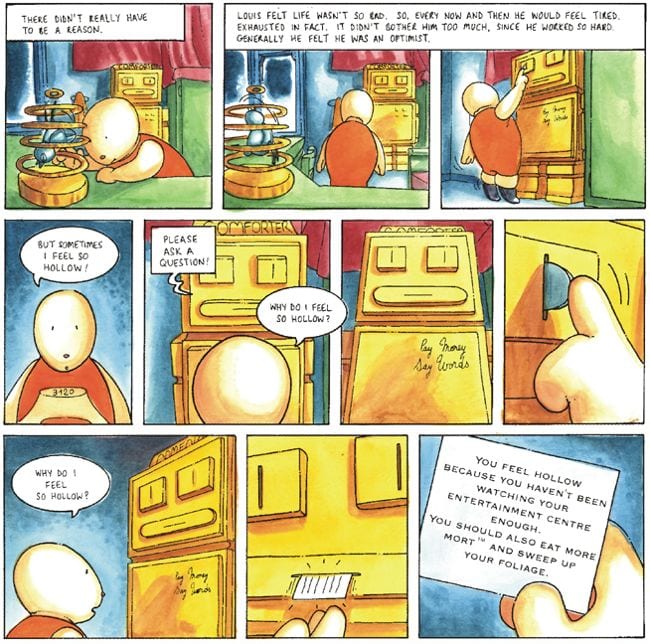

CHALMERS: By the time we got on to do Louis, we wanted to do something drastically different. You know, something much brighter and more slapstick, and certainly more readable, more approachable. Also, we realized that to tell a story, effectively, you benefit from having a lot of tension; and one of the things that we could build the tension within was the contrast Louis’s rounded nature set in juxtaposition with the darker machinations of the society or system that Louis has got to live in. It created an effective -- and we hoped -- powerful contrast.

You’re right Gavin, Sandra proposed the concept: the idea of an anthropomorphic character trapped in a cell and wanting to escape.

I’d carried the idea around with me and realized -- at first I thought, well that’s The Prisoner and then -- that’s the human condition. In a sense we’re all kind of limited to ourselves, and you’ve got room for metaphors -- but there’s not that many major metaphors you can apply to a story, or different story types; there’s really not that many, basically it boils down to the fact that you’re trying to talk about some deep, philosophical question, you’re trying to put that out there in a way. We realized maybe that a novel approach would be to have it look like a children’s book and have an unhappy ending, because nobody’s done something really like that. Because people say it’s really like The Truman Show, which we’d never seen. You know, because of the –

LEES: — Props, the scenery at the end.

MARRS: — When we did watch it I thought, “Oh God.”

LEES: "That’s exactly the same scene!"

MARRS: I guess the ideas are in the air, a product of the times.

CHALMERS: That’s also asking a big question, what is the reality that you hold so dear, you know, and how fragile is it? I think that’s the main thing, it is a deep question, it’s a powerful question. And maybe, there’s the human condition again.

MARRS: It’s something that was in Strange Weather Lately, as well, the scenery as a kind of theater backdrop, or cardboard cut-out.

LEES: Which is going all the way back to Plato and the shapes in the cave.

CHALMERS: The Republic.

LEES: Yeah.

CHALMERS: When you’re asking, like I said, deep, deep -- and I don’t think I’m deep or something -- philosophical questions, you’re trying to put them in an interesting way that’s the challenge. When you make a film, or write a book, or even probably with music, it comes down to quite primal things, quite fundamental things. People have been trying to answer and ask these questions forever, they think -- well, we didn’t sit down and say like “what we’re gonna do, we’re gonna flip Plato into the mix…” -- basically again we just tried to solve the interesting challenge of telling the story as effectively as possible, and making a rhythm and a readability; keeping it very sparse and making it readable and allowing children access to it, for the first time having adult themes -- not adult as in sex in the American sense or usage of the adjective -- basically allowing a way to possible readership.

LEES: Yeah, which is more thoughtful really. You’re no longer dealing in abstracts, you’re articulating these ideas through something concrete.

CHALMERS: Perhaps. I don’t know, consciously -- well yeah, yeah, yeah, we did sort of take it very seriously. We took a while to think about it, and we made Vermin as a kind of stepping-stone, a practice for doing work in color, a very simple story. I think the efficacy or effectiveness of a story can be measured only really in hindsight; you can’t say while you’re working on it, “Oh, this is working well,” you’re never really ever sure. We got great feedback, I mean, the American market really took to Louis — Red Letter Day, we got all sorts of film companies interested, and even before San Diego became kind of Hollywood; even award-nominated, and stuff like that. We just really didn’t expect it to be…

LEES: An Ignatz Award, wasn’t it you were nominated for?

MARRS: And an Eisner. Two Eisner award nominations in fact!

LEES: Two Eisners as well? Wow.

CHALMERS: We met Will Eisner. He’s sadly no longer with us, isn’t he?

LEES: No, he passed away about five years ago now.

CHALMERS: He was a great guy, a lovely guy.

It was quite breathtaking, I think we were quite surprised; we didn’t realize that people were that bothered. Do you know what I mean? [Laughs]

LEES: Yeah. It was a different time back then, too. The Internet was only really beginning to take off in a big way, so you didn’t really hear people talk about you much outside of select publications and local press like The List. So, I can imagine that being quite surprising and flattering.

CHALMERS: It was strange to be getting so much attention, but we’d deliberately never limited ourselves by geography (even before the internet became so common or taken for granted). Sending review copies all round the world to magazines and fanzines like Anodyne, Drawl, Poopsheet, Bild & Bubla, Zone 5300, for example: The Maze was reviewed in the American fanzine Factsheet Five, and Strange Weather Lately got a mention in the German magazine Panel and was reviewed in The Comics Journal. Now fanzines exist in a kind of dynamic equilibrium with blogs and geographical boundaries blur. But back in the mid-nineties it was quite a different world. As we learned about making comics we also tried to understand the world of comics. We visited both San Diego Comic-Con in 1998 and the Small Press Expo and handed out little mini-comic samplers from Strange Weather Lately. We also handed out special Strange Weather Lately cans of beans and because it was close to Bethesda we visited Timonium and the Diamond folk.

And we traveled every year to Angoulême, the comic festival in France, the biggest comic festival in the world with over 250,000 people attending. It’s very inspiring to see so many buses of children, young people really passionate about comics. Both genders too. Not only girls into manga but also people who are fans of the more traditional BD. We would be able to meet other industry professionals, from all over Europe, Het Raadsel from the Netherlands, Panel and Starpazin from Germany and Switzerland respectively, Finnish publishers and journalists from all over the world. Each year a different nation is represented and there’s a focus on that country’s comic culture, for example Korean comics or American comics. And talking and listening you learn how they were doing, and also make new contacts and build relationships -- they even have American and Canadian visitors despite the relatively large distance and you can go and see exhibitions, there’s original art on display and very creatively designed exhibition spaces.

CHALMERS: Before we’d be regularly surprised by people’s interest locally. Just as the internet began to take off we received an email from a Glasgow scout troop, the 5th I think… they emailed us asking if they could put on Strange Weather Lately as a play. It was to raise money for a new roof for their scout hut. Don’t know if it ever happened!

And once on a windy, quiet midweek night I got on a bus and there was only one other passenger, a young guy, and we silently, politely acknowledged each other. When I sat down he asked me about the book and about the writing process… if it had been cathartic.

But the interest we received after the award nominations was very varied and we realized it was coming from all over the place.

You put your book out there, and we got good feedback with Strange Weather Lately, but that was a totally different level. And also there was so much more risk at that time in doing a full-color book, because we’d worked and supported our local community; and it supported us, in a sense, and people were quite aware of that, up to that point. But the world’s gone so global now.

LEES: Exactly. Did that have any impact on your decision to do another Louis book, rather than another serial? The fact that it was easier to get publicity and you could be visible in other ways than just the Diamond catalog?

MARRS: We actually had already decided not to serialize anymore and to produce only books -- the term graphic novel wasn’t used so much at that point yet -- but more because of what we talked about before, all the extra little bits of work around each comic. Our feeling was that a finished book was more satisfying for the reader.

CHALMERS: The fragmented nature of Strange Weather Lately suited the fragmented nature of serializing. But you’re right in a sense, doing the first full-color book had been quite nerve-racking and we were encouraged to do another book by the amount of interest, the nominations and the positive reviews.

LEES: It seemed to take it in a slightly different direction; it took this conceit of Louis, but took him out of his original prison into a very different one: the bee farm. It seems a very political statement -- a scathing indictment of the human condition. You have all these bees -- are they even real bees? They look like people in costumes -- who all conform and, literally, dance to the same tune because of the lies that are fed to them. Were the bees a deliberate metaphor?

CHALMERS: Yeah, an allegory or a metaphor. The idea that we’d had was not to do another Louis story, but we’d fallen in love with Louis and we realized we wanted to re-use the character; to use the character again, but not to repeat the first book. And again, the preoccupations are still there to a degree, but this time we explore the idea of language as a prison. As you say, also the kind of “herd” mentality almost certainly. But the bees were diseased as a metaphor for just allowing people to die; the price that’s been paid for relative affluence. I don’t think anything’s apolitical, or you can’t really say something’s political, because there’s a danger where you over-politicize a piece of work, you can affect the aesthetics; it can change the balance. But, I think having something like bees is quite good fun, because you can show very quickly, visually, something’s not quite right. You can say, just with a gesture, that this person’s like you or I, and isn’t quite right; there’s something wrong. So, we had a lot of fun with that, it’s more like a journey in structure; we took an approach that at least let us do something new, the journey structure, and look at our society. And we just had a think about that. It seems frightfully naive, now, to say, “Oh, this is wrong.” If you look around you, people not talking about it is very political; that’s political, you see what I mean. I know we’re not in Africa, and we’re not dying with flies in our mouths, but if you’re not aware of it then…

LEES: Right.

CHALMERS: [To Marrs] You changed the palette, you chose softer, sandier, desert colors.

MARRS: Yeah, to go with the desert scene.

LEES: But why bees? The idea of “bees with disease” is like some horrible Dr. Seuss line.

CHALMERS: We’d wanted to examine language, to explore the idea of language as a form of prison and also take a look at our unegalitarian society.

MARRS: Your typical kids’ book really.

CHALMERS: Heh. So bees: they’re very industrious, hard working and they have a recognized structured social system. And you’re right about the horribleness of “bees with disease”. That phrase, along with “urinate on their heads for ha ha”, both the language and the ideas, childish and repellant; unsavory, things people would rather gloss over or ignore. We have bees in danger now, serious eco and environmental issues, but at the time, then, it was convenient from a linguistic point of view. All the Louis books question our attitude towards food and our surroundings.

LEES: So, that must have been 2001 that Lying to Clive came out. Something you did around then was the 9/11 Emergency Relief anthology. That was an interesting story, because you seemed to go back to pure autobiography. Was that strip a complete retelling of your experiences?

CHALMERS: Yes, in a sense.

MARRS: That was a requirement of the story, actually. When Jeff Mason at Alternative Press asked us if we wanted to write a story for the anthology, one of the main requirements was that it had to be approached from an autobiographical angle, which, I think I remember at the time, we thought, “How are we going to do that?” because it felt misplaced, almost, to write about yourself when something like this happened, and it’s a bit tricky to approach it that way.

CHALMERS: It seems that the only dignified response would have been silence, to be honest. We were quite taken aback, because we’d been there, we got there the day before, and our friends who we were staying with were booked on the same flight that was high-jacked... They were booked on the high-jacked flight, but the next day: they were planning to fly to California for a wedding. So, we have several people who were mutual friends, people I’d studied with when we were younger that were in the air, at that point, and some of the planes were turned back to Peru. No explanations given for the closing of the air space. It was quite an intense time. We didn’t put all of this experience in the story, and I think part of the story involved the fact that we weren’t very comfortable, we didn’t know what to say, like, “shit,” you know, “Bollocks, what the fuck, you know?”

LEES: Yeah. I think that was Johnny Ryan’s response. [Laughter]

CHALMERS: Probably — aye — verbatim. Maybe telling the story’s quite important, because a lot of things disappeared, like the jumping man, and “War On America” newspaper headlines. There’s a lot of things that were simulated. I don’t think we were against, or for, America, it’s quite an unbiased piece — America’s the most multicultural place in the world, you know. Because we were there we were asked and it was nice to be included — nice... [Laughs] but it was quite a difficult story to write…

MARRS: Obviously, we wanted to do it, otherwise we wouldn’t have done it.

CHALMERS: To be asked to do anything, “Would you produce a story for us?” That’s always quite a good thing. You don’t say “no” very lightly, even if you’re not quite comfortable. So, we try to convey some of that in the story.