LEES: Sure. Your stuff wasn’t really part of any Glasgow comics scene anyway. There was a tradition in Glasgow with Electric Soup and the small press which was very humor-based. You seemed to be — I don’t want to cheapen the humor comics by saying “elevating” -- but you were doing something that was more literary, and certainly the art was a lot more representational, less cartoonish, than other people who were working in Glasgow. Who was feeding into that, if it wasn’t local artists, who fed into the work you were producing then?

CHALMERS: I think, probably, like, the only honest answer is to say everything in our lives, as with anybody being creative, if you’re making music or making language work for you, then you know that it’s every event, every experience that you’ve had that informs the creative process. I think that that’s the main fuel; neither of us was massively influenced by any particular cartoonist or writer.

CHALMERS: Don’t really know what fed into it any more than just our lives.

MARRS: I think, for my part, the art style was obviously influenced by European comics.

CHALMERS: By what you seen, what you’d seen as you grew up.

MARRS: Yeah, yeah. Artist like Bilal or Moebius: but also painting. One of our first short stories was based around a Van Gogh painting.

LEES: John, did you feel you were coming from a Scottish literary tradition? There are recurring themes in Scottish literature, in Archie Hind’s Dear Green Place and in James Kelman's books that explore the idea of writing or of trying to create music or art and some of the factors that can be working against that.

CHALMERS: I think you’ve also got to have an awareness of literature. Or I certainly felt like I’d better know a bit about literature; I’ve always read ever since I was tiny, but you know, if you want to make something new, you’d better know what’s out there. I don’t even think that there’s any doubt. You’d have to feel as if what you’re putting out had some worth; otherwise, it’s a colossal risk, it’s a colossal thing to do.

LEES: Sure.

CHALMERS: …and for me, writing, like I think I didn’t feel as if I was coming from some kind of Scottish tradition, but, I think the ideas there: they are quite universal, the idea of art not being able to be finished; or the gap between the art and what you would like it to be… It’s a huge philosophical question, if you see what I mean.

LEES: Yeah -- that's it. It’s the idea of the artist constantly second-guessing themselves, probably subconsciously wondering what the hell they’re doing — those Gaugin questions: “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?”

CHALMERS: You know, you’re addressing these when you write.

But you’re wise not to think of it as elevated, because people look at comics as lowbrow already. We were quite lucky that the literary establishment accepted it, because the Strange Weather Lately graphic novel was the first to appear at the Edinburgh International Book Festival.

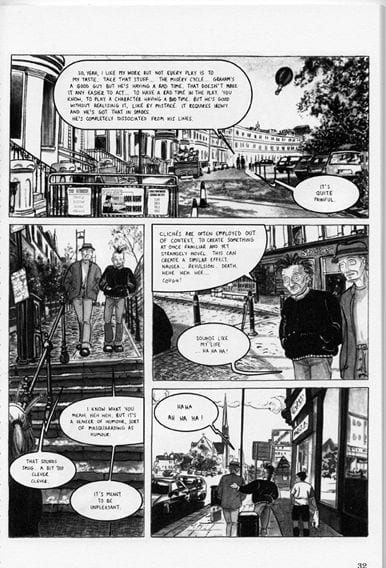

LEES: In that book you, Sandra, developed this photo-realistic style, where all the locations were real places in Glasgow, even though it’s never really mentioned in the comics at all that it is Glasgow. I was wondering if that had been influenced by Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, where he had Unthank -- Hell -- rendered quite obviously as Glasgow — though, again, I don’t think he ever mentions it — and playing up to the inherent grittiness and depression of the city, but also trying to elevate it into somewhere that would be romanticized in the way that Paris and New York were. I think you do that in Strange Weather Lately, too. You have this urban realism, but you also have a lapse into surrealistic fantasy. I was wondering if that was a conscious decision to follow that tradition?

MARRS: It wasn’t a conscious decision to follow that tradition on my part -- I hadn’t read Lanark.

CHALMERS: I think, we chose Glasgow mostly because it was here, although I grew up in, and am fond of the city, and know it, and you were kind of getting to know it, exploring it.

MARRS: Yeah, and I guess romanticizing it, because I was discovering it and finding it so beautiful, really.

CHALMERS: There is a kind of awareness… I was aware of Lanark and Unthank, and the whole literary tradition… but one of the main themes of Strange Weather Lately is that of loss, and you’ve got the loss of distinction between the reality of the comic and the reality in the play. So it was an effective way of exploring that theme, but it could be an every city and Martin Nitram could be an every person, in a sense.

When Lanark was released it had an enormous impact on the culture, reading it, and discussing it with friends -- everyone in a way could relate to it and to its Glasgowness, even in the fantastic or fantasy passages it still seemed very recognizably Glasgow. With Strange Weather Lately the city actually appears to the reader since it’s a graphic novel so I would imagine the effect is quite different, but essentially yes, there was an awareness of Lanark, a touchstone of Scottish literature and also of other Scottish writers, James Kelman, Gordon Legge, and of other writers… Kafka and Ibsen and before them Chaucer all used fictive worlds, meta-levels, to comment on or contrast with the societies in the stories they were telling. It seems terribly pretentious to talk in terms of these writers. But in terms of the ideas, and the tradition then, yes, there was an awareness, but it wasn’t necessarily a conscious attempt to draw forth comparison or make an allusion to that particular book.

In a sense the story told itself and kind of poured out -- there was an urgency, and some things, the dreamlike world were necessary for the telling if that makes sense.

The Glasgow setting was also very convenient.

MARRS: I think it was a conscious decision not to name the city and also…

LEES: Oh, sure.

MARRS: …It’s not really Glasgow: it’s places from Glasgow; it doesn’t make up for Glasgow.

CHALMERS: It’s distorted.

LEES: Right, yeah. Just like when you see a film set in a city you know well and you realize the continuity between locations is all wrong. It wouldn’t happen like that in real life, so the city becomes fictionalized in a way.

MARRS: It’s kind of made-up and mixed-up a little bit.

CHALMERS: Also, the beauty of the architecture, I think it’s a very beautiful city. The awareness of a Scottish literary tradition, I think, goes back to just being aware of what’s out there already, and maybe there’re a few literary allusions that people would pick up on. But you’re always writing, basically-- I certainly at that time was writing -- for nobody else apart from Sandra, and myself, really, to be quite honest. I wanted to write something that was funny and effective; but you don’t know if you’re going to be able to do that, but I was more concerned with preoccupations, like the differences, like I said, the idea that the art maybe doesn’t come up to the expectation, or the unfinishedness. And I don’t think that’s a peculiarly Scottish thing, although as you said, it does appear in a lot of James Kelman and in Archie Hind’s Dear Green Place. There is a literary heritage there and a recurring set of themes, but I think any piece of art, or literature, or work is basically trying to fundamentally address a philosophical question, in a way. And one of these is whether you exist without people observing you, and another is the gap between what you’d hoped for and what you actually get; and that’s true of life, as well as art, or memory, or anything really. These are just some of the ideas we sparked around with, just wanted to investigate, they’re interesting ideas so we wanted to put them into a story.

I don’t think there’s any conscious choice made in selecting Glasgow, apart from the very practical one, and also, it maybe worked, it worked because you did romanticize it, in a sense, and I was familiar with it. But there were some strange things, like we needed the urban edginess... you know like the “Al Jolson” that used to be graffiti done on walls around Glasgow, I found it quite perverse, quite a strange thing. And, different little bits of social commentary that can be put it. Edginess that you get, you wouldn’t get if you set it in a village.

MARRS: No. I think it was our life, as well.

CHALMERS: Yeah. There’s a degree of autobiography.

MARRS: We used our flat as a basis for Martin Nitram’s flat, just for example.

LEES: Right. I thought this place looked familiar.

MARRS: Just because it’s there and it’s easy to refer to, and stuff like that.

LEES: Were the characters based on real people, either their physical appearance or their personalities?

MARRS: They weren’t directly based on people we knew, but obviously some aspects must have come out of the people that we knew. Like for example, Peter, Martin Nitram’s friend, with a punky hairdo was not based on a real person, but is similar to some people we knew.

CHALMERS: Obviously in terms of the writing, the characters are probably a part of some messed up part of me. We wanted to bring characters that are interesting and believable; there’re probably some archetypes… the detective for example.

I like fucking about with the detective fiction genre, I like that whole idea, but I didn’t have a particular prescription for the image of the detective character, just wanted somebody who looked slightly down on their luck, slightly battered I think. We’re lucky that we get on, and trust each other, and I didn’t go: “oh that’s not right!” Usually you did produce the drawings and I thought , “yeah, that’s great, that’s the detective.” Sometimes, I’ll doodle characters a bit, but more for the Louis world rather than the photorealistic style. We didn’t take pictures of people and use them, or anything like that. We didn’t go around, you know, and steal souls.

LEES: Yeah, OK.

MARRS: We did take pictures of Glasgow and used those. And I guess that a comic set in Glasgow, at the time, was unusual and the newspapers here were interested. It was before comics were acceptable again or fashionable.

CHALMERS: Glasgow kind of became a bit of a character in the story. It did get us a lot of interest, which was surprising; I think people thought we were millionaires, or gonna be millionaires because they saw us in the paper, at that time. [Laughter] It’s quite naïve, isn’t it? Pre-celebrity culture, almost, in the mid-nineties; you’ve got to remember, it’s changed now, isn’t it, fifteen years. That’s a massive amount of time.

LEES: Oh my goodness, yeah.

CHALMERS: A lot can happen in that time.