From The Comics Journal #216 (October 1999)

Megan Kelso and I first met about seven years ago, through a mutual friend who knew we were both cartoonists. I was excited to meet her, since a woman who draws comics is a relative rarity, but a little trepidatious about being introduced to someone solely on the basis of shared job description. To my relief, we got along easily, and on that occasion comics took a back seat to less obsessive conversational topics. It was only later, and over time, that the obsession would heat up.

Megan was, for the most part, blissfully unaware of the history and content of mainstream American comics, and it was clear that this was to her advantage. What thrilled me and the other cartoonists in our circle of friends about her early work was that she seemed to be inventing comics on the fly; she knew she wanted to tell stories with words and pictures, and was exploring how to do it free of the conventions relied upon by the rest of us. Her work forced us to reexamine a lot of the things we took for granted. We were all interested in tossing out the old hats of comics and haberdashing new ones, but while most of us were earnestly folding newspaper into pyramidal shapes, Megan and Jennifer Daydreamer were sporting velvet-covered, plumed bonnets festooned with ribbons and mother-of-pearl.

Over the years, Megan has continued to challenge herself, deepening her commitment to the craft and to the art of comics, selectively appropriating established conventions if they serve her needs, rejecting old habits that interfere. Even though her work ethic makes me feel like a hack, I am inspired every time I see what’s on her drawing table or leaf through the rough penciled pages of a story in progress. Most inspiring, though, is her obvious love for her medium of choice, and how that love serves her efforts to get at the more ineffable aspects of human experience. I’m very happy that there’s a bookshelf full of unwritten, undrawn comics by Megan Kelso waiting for me in the future.

Jason Lutes

Seattle

Sept. 15, 1999

GARY GROTH: Let’s start off by getting some background information, since I don’t know anything about you: where and when you were born, and where you grew up.

MEGAN KELSO: I was born in 1968 here in Seattle, and I grew up in Seattle. I lived in the same house for the first 18 years of my life on Capitol Hill.

GROTH: You may be the only native Seattle cartoonist still living in Seattle.

KELSO: Yeah, maybe I am.

GROTH: You went to Evergreen [College]...

KELSO: I actually went to art school first, I went to the Art Institute of Chicago, which is kind of a fancy, expensive school, and I lasted one semester.

GROTH: Was that directly after high school?

KELSO: Yeah. Well, actually no — I took the first semester off after high school and went to Central America and did some traveling. I started art school in the middle of the year, which may have been part of the problem. I just didn’t like it, and I knew my family was spending a lot of money, and I knew that I would be paying off loans for the rest of my life, and my main impression of what that art school was for was to launch you into the Chicago art world, and I didn’t see myself doing that, and the academics were really crappy even though they were supposed to be really good. It wasn’t working.

GROTH: By academics, you mean the actual courses in drawing?

KELSO: The studio classes I thought were OK — some of them — but to get a BFA, you also have to take Art History, English, all that stuff. And those classes were just shitty. And I kind of figured out in that semester that I did in fact just want a liberal arts education, I didn’t want to study just art at that point. I left after a semester, which my family thought was a bit premature, but I felt I was making the right decision. Then I took about a year off, and went to Evergreen.

GROTH: I’ll get to that, but let me go back to your upbringing. Can you describe your childhood, and how you got interested in art and cartooning?

KELSO: I’ve been drawing since I can remember.

GROTH: Was that encouraged?

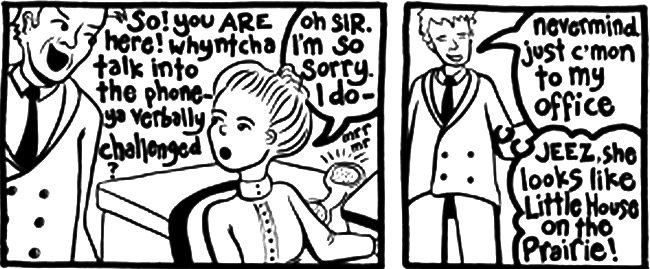

KELSO: I remember we had this drawer of scrap paper. My parents would throw paper into this drawer, and my sister and I could use whatever was in there. The two of us drew a lot together as kids. We would sit at the dining room table and draw lots of women in big bouffy dresses, Little House on the Prairie-type stuff. My dad’s an architect, so he could draw really well, but he didn’t like to, and I would always try to get him to draw pictures for me. He would say, “No, you should draw.” So yeah, it was encouraged, and I definitely got the props for drawing when I was a little kid. I’ve talked to a lot of cartoonists who experienced this: you’re in school, and people are really impressed that you can draw, and they want you to draw pictures for them, and that’s part of your character in class, and that was definitely the case for me.

GROTH: Any other siblings?

KELSO: Just one older sister.

GROTH: What was your upbringing like? If your father was an architect, I assume it was middle class, upper-middle class.

KELSO: Yeah, we lived on Capitol Hill. They’re pretty liberal; we lived in this funky old house. It was a really cool house, but it was the shabbiest, most unkempt house on the street.

GROTH: Mmm-hmm. Did you appreciate that?

KELSO: [Pauses.] Well, at the time I would swing back and forth between wanting more “normal” parents and feeling kind of proud. We did a lot of backpacking when I was a little kid, so it seemed like we were hardly ever home on the weekends. My parents weren’t the kind of people who were out there on Saturday working in the yard, making everything spiffy. And I didn’t watch a whole lot of television. I don’t remember any strict rules about it, but growing up all we had was this tiny black-and-white TV, and it just wasn’t a big part of life. My parents always had very definite opinions about aesthetics, taste and culture, and there was this sense of, “Of course you wouldn’t want to watch that stupid show!” So I think my sister and I were, to a certain degree, shamed out of watching a lot of TV, because there was a sense that it was a waste of time.

GROTH: A subtle pressure?

KELSO: Yeah, We’d go over to our friends’ houses and watch TV.

GROTH: You said that sometimes you wished your parents were more normal. Were they markedly unconventional?

KELSO: Well, as an adult seeing the larger scheme of things, they weren’t that unconventional, but I think most kids have this idea that everybody else's parents are more normal than theirs. So I don’t think they were that offbeat, but l guess they were...

GROTH: Are they intellectuals?

KELSO: Yeah.

GROTH: Did that have a profound effect on your growth as a person and an artist?

KELSO: I definitely came from a bookish family, and both my parents and uncles made things — instruments, books, photos, crafts. Making art seemed like a normal thing to do in my family.

GROTH: Did you read a lot of books as a kid?

KELSO: Yeah. A lot. That’s pretty much all I did.

GROTH: So when you were a little older, in high school, what was that like? I mean, the American High School Experience can be traumatizing [Groth laughs].

KELSO: Well, I went to Garfield, which is one of the best public schools here in Seattle, but I would still say that about 75 percent of it was a waste of time, and I skipped a lot of school. I was disconnected from the high school life. I mean, I had friends, I had plenty of friends and I didn’t feel alienated socially in that way, like, “Nobody likes me.” I had plenty of intellectual pretensions, but very little interest in school. I showed up, did what I had to do, and left.

GROTH: But you didn’t feel inordinately alienated.

KELSO: No. And I had maybe three really good teachers over the course of that four years who kept me feeling like it was worth it. They had a really cool graphics program at Garfield, offset presses and stat cameras, and you could do silkscreens or print magazines... it was really amazing, and I wish I had done comics at that time because I could have self-published like crazy. But at that point I really hadn’t put it all together. Adrian [Tomine]’s probably the only high school student who ever has! So there were some neat things at that school — it wasn’t 100 percent horrible.

GROTH: At what point did you feel an affinity for cartooning and comics?

KELSO: [Pauses.] When I went to art school, I wasn’t thinking of comics or cartooning, but pretty much everything I did in my studio classes was trying to incorporate images and text in some way. The photography work I did, the drawing, I was always putting text in there and I remember getting a lot of flak from teachers about that. I remember this one drawing teacher I had kept asking me if I felt like my drawings weren’t powerful enough, so that’s why I was using the text, to kind of back them up.

GROTH: Hmmm.

KELSO: But I was never thinking of it as comics. When I look back on that stuff, I think, “Wow.” I was clearly headed in that direction.

GROTH: But you weren’t completely aware of that.

KELSO: No. I didn’t think about doing comics until I was at Evergreen. I’d been there about two and a half years, and I hadn’t really done any art at all —you know, art classes. And then I had this boyfriend who was really into comics, and he tried to get me to read some. I remember it was right at the point where Pete [Bagge] was finishing Neat Stuff and starting Hate, and then I saw one of Julie [Doucet]’s early issues of Dirty Plotte, and something came together. I said, “I bet I could do that, I bet that could work. “I knew that I wanted to tell stories and I knew I wanted to draw, and I knew I wanted to write, but I couldn’t figure out how it would all fit together; comics didn’t occur to me.

GROTH: It didn’t occur to you that there was a form already in place.

KELSO: I knew that comics were out there. Even in high school I knew people who read Love and Rockets, but it didn’t really sink in. Then it sunk in, and my last year at Evergreen all I did was work on getting out that first issue of Girlhero. I actually had an academic contract to do it.

GROTH: So in your teen years you didn’t read comics, you didn’t copy comics.

KELSO: No. I read comics when I was a little kid —Peanuts, the odd Richie Rich — but didn’t have any interest in comics, really.

GROTH: And your instructors in Chicago acted like this was an illegitimate hybrid you were doing, combining words and images?

KELSO: Kind of. They were sophisticated enough to know that images and text are OK in the art world, but there was this suspicion, like: “She must be trying to jack up the power of the drawings with the text.” Like that was cheating.

GROTH: But you wanted to tell stories?

KELSO: Yes, because I’ve always written. I was a very frustrated writer/artist before comics saved me [Groth laughs] — I always drew a lot and I always wrote stories. When I was a little kid I used to make books, I made a whole series of books as Christmas presents for my family — they had chapters and illustrations. But then I lost it somehow. When I was in college, it felt either/or to me for some reason.

GROTH: You put out Girlhero #1 [the minicomic, as opposed to Girlhero #1, volume 2] in 1991, while you were at Evergreen... what was the impetus behind publishing the issue itself?

KELSO: For my academic contract, I had to have some sort of final project. At Evergreen you can do these independent study projects. In my proposal I told my professor, “I will produce a comic book!” And I went around bragging to people that I was going to do this comic book for months before I actually started, and everyone was really impressed. I had no idea how much work it was. No idea.

GROTH: Explain how an academic contract works.

KELSO: Well, every quarter at Evergreen there’s a number of professors in the academic contract pool from a number of different disciplines, and if there’s something you want to study, you make a proposal to one of them, and then if they accept it, the two of you negotiate what you’ll read, what papers you’ll write, to make it a certain number of credits, and then you meet with the professor once or twice a week (depending on what you’re doing). My proposal was to make a comic book, and the guy who sponsored me was a science-fiction writer, he knew nothing about comics.

GROTH: Who was that?

KELSO: His name is Tom Maddox. He was great. Mainly what we talked about was the creative process. And I really didn’t know that people were doing minicomics, but everybody at Evergreen was off to Kinko’s, making zines. I didn’t discover that there was this whole world of minicomics until I graduated, moved back here and started meeting other cartoonists.

GROTH: So, what prompted you to actually do a comic? You finally realized that this hybrid form was ready and waiting for you?

KELSO: Yeah, so I told this professor and everyone I knew that I was going to making a comic, and I was not making a comic, and I was starting to get really freaked out. I started photographing what I wanted the comic to be, and it turned out to be 15 photographs and it was kind of telling the proto-”Bottlecap” story. It wasn’t a comic, but it was a story told with sequential images and text. Once I got that out, I started doing “Bottlecap” as a weekly strip (called Animata, after one of the other characters) in the Evergreen newspaper. So the first comics I did were just one strip at a time. I realized that wasn’t going to work for me, so I started expanding it into a story.

GROTH: How did you choose the subject matter (“Non-Biodegradable Youth”)? It looks vaguely autobiographical.

KELSO: The very first strips I did were these weekly Animata strips for the paper. But I wanted to have another story in the comic, and I’d co-written “Non-Biodegradable Youth” with my friend Joe just for fun. It wasn’t originally intended to be a comic; we were just messing around. But at the time it seemed easier to start with something already written and turn it into a comic, so I gave it a whirl.

GROTH: I see.

KELSO: By this point I was reading more comics, and I started getting a handle on what a comic actually was. “Non-Biodegradable Youth” was just me ripping off the hipster comics I was reading at the time — not autobiographical at all, really. I didn’t grow up in Suburbia, for instance.

GROTH: How conscious were you in developing an approach to drawing cartoons, creating your own stylization? Is it something that just happened, or was it a calculated choice?

KELSO: Well, in the beginning I was really embarrassed by word balloons, I found the classic comics look... it just seemed so... It’s hard to say this because of what I know now, but at the time I hadn’t seen a lot of comics, and I just thought the whole thing was sort of cheesy, and when I did this story I felt like I was faking it. I didn’t feel comfortable doing it; it didn’t feel like me. So I was really into this idea of, “How can I do comics with no word balloons, and no borders, and no nothing?” That’s why “Bottlecap” looks the way it does. I really had a problem with the word balloons. And I tried to do comics without them, and then discovered that there’s a real good reason [Groth laughs] for their use — but I learned it myself, and I think that really helped me, actually.

GROTH: That’s interesting, because “Bottlecap” has this anarchic visual look to it.

KELSO: Yeah. Do you have the first issue? [Groth produces it.] At the beginning, I wanted to have everything flow from image to image. I didn’t want to chop it up into lots of little panels. I don’t know why... now I like lots of little panels. At the time, I thought lots of little panels were cheesy. Plus, I think I was also influenced by (this is kind of embarrassing) by, um, who were the guys doing those painted comics, the really sort of splashy layouts and stuff?

GROTH: Jon J. Muth, Kent Williams?

KELSO: Bill Sienkiewicz.

GROTH: Bill Sienkiewicz, right.

KELSO: I was really impressed by all that stuff. I really liked it. Because they didn’t look like comics, I guess.

GROTH: They sort of look like an art-school version of comics.

KELSO: That’s the part that I liked. So that’s where I started: I didn’t want my comics to look like comics.

GROTH: Can you tell me a little about your education in comics, and how you became more comfortable with using the conventions of comics?

KELSO: I have to confess that I really haven’t read a lot of the canon of comics. I feel guilty. I really think my education started when I met all these cartoonists in Seattle, they knew a lot more about how to make a comic than I did. Jason Lutes, Tom Hart, Jon Lewis and Ed Brubaker, James Sturm, David Lasky... I met all those guys at the same time: all of them were read-every-comic-ever-made kind of people, totally understood comics. And yet, they too were just starting out in careers of their own, so I was in the same place as them, but in another way years behind them. And I learned a lot just by talking to them, reading their comics, and having them tell me about mine.

GROTH: Let me get a chronology straight: you did your minicomics in school in 1991, then you went on to publish your first commercial issue — to use the term loosely — of Girlhero in 1993. When did you get back to Seattle?

KELSO: I graduated in spring of 1991 and moved back to Seattle that summer. And I didn’t do any comics until maybe the fall of ’91. There was this little newspaper in Belltown called the Belltown Dispatch, and the editor, a friend of a friend, called me out of the blue and said, “I hear you do comics, do you want to do a comic for the Dispatch?” And that got me back on to “Bottlecap.” The chance to do a comic in the newspaper got me doing “Bottlecap” again, and that’s where the first few pages of “Bottlecap” in Girlhero #1 came from. It got me back in the groove. So I was complaining to my sister Jenny about how I didn’t know any cartoonists and I was trying to do this comic all by myself, still exceedingly ignorant about how to make comics, really frustrated, and one day she said, “You know my friend is living with this guy who works at this comic book publisher here in Seattle, and his boss’s girlfriend is a cartoonist. It was Jason, he was working at Fantagraphics, and so she was talking about Julie [Doucet].

GROTH: Have you ever met Julie?

KELSO: I eventually met Julie, but not back then. So I met Jason, and through Jason I met everybody else.

GROTH: [Laughs.] Great lineage.

KELSO: Yeah, I don’t know what I would have done if l hadn’t hooked up with some fellow cartoonists at that point.

GROTH: Can you talk a little about how your circle, your generation of cartoonists, socialized and helped each other, and how you learned from them?

KELSO: Um... well, I met Jason —

GROTH: You mean Jason Lutes. Let’s keep the Jasons straight. Jason Little worked for us, too.

KELSO: Oh, right. I’m sort of exaggerating when I say that I met Jason, then I met everybody. I knew Jason almost a year before I met Ed, Tom and Jon, but anyway, Jason and I hit it off immediately. And I remember that he told me about the Xeric Grant, he read about it in The Comics Journal, and told me that he was thinking of applying for it. It was right about the time he was starting to get the Jar of Fools strip going in The Stranger, and I was working on “Bottlecap,” and we would get together and draw. Jason’s great, he’s a natural teacher. He could tell I needed a lot of help. [Laughter.]

GROTH: He was generous.

KELSO: It seems like we developed that kind of relationship early on, where we would occasionally draw together and I would go to him for help, because, my God, he just draws so well, and he understands comics really well. And then I met the other boys, Ed, Jon and Tom, and they had this vision of conquering the world through comics, and so they were all living and working together in this tiny apartment. To me they were an instant unit. So then I applied for the Xeric grant, and Jason decided not to, because he hadn’t gotten Jar of Fools together the way he wanted to, and I actually got the grant. It totally blew me away. I met Dave Lasky around that time too, because he had gotten the grant the same time I did and had moved to Seattle from back east. And then within a year, year and a half, Jason got a grant, Tom got a grant, Jon got a grant, and I really don’t know if we would have coalesced as a group if that hadn’t happened. All of a sudden all of us had the same concerns: How do you self-publish a comic? I think that was a really sort of galvanizing factor, all that Xeric money.

GROTH: So, would you guys meet regularly, or semi-regularly?

KELSO: Well, after I met all those boys, they basically couldn’t get rid of me, because it was this amazing discovery to find people who I liked personally and whose work I really respected. I’d hit the jackpot. Eventually we got this idea to have a more formal group where we could bring in our work and have each other critique it or help with a problem and just talk about comics. And for a while, maybe a year, we had real monthly meetings with a minutes and everything.

I remember everybody was pretty shy about critiques at first. I think often Jason would be the first one to offer a criticism, since he’d been to art school. But then it was like the floodgates were open and everybody would jump in and offer everything from suggestions for the plot to how you drew the panel border to perspective, how to draw certain objects. It could be overwhelming, but for the most part it was all very respectful and loving. But after a while most people came in saying “I only want comments on timing or transitions” or whatever because otherwise you’d get your whole comic revamped.

It sort of started out with a somewhat small group of people, and seemed to strike a chord, and suddenly a lot more people started coming. It got kind of big, kind of unwieldy, and became more of a social occasion than getting work done. And I — a bunch of us — dropped out at that point, because it just wasn’t going the way we originally wanted.

GROTH: It lost its focus and intensity?

KELSO: Yeah.

GROTH: Was there a sense among you — was there a sense of excitement that you were all striving to create art out of comics?

KELSO: Yeah, I think there was a sense of excitement over getting money too.

GROTH: Yes, that always helps.

KELSO: Yeah, I mean, I could speak for myself, and I think most everyone else when I say that there is real validation in being awarded a grant. But as it turns out, self-publishing is a total drag, and I for one felt pretty downtrodden by the end of my experience. But at the beginning, you send off this idea, this comic you’ve been working on and someone says “yeah, this is great, here’s some money, go knock yourself out.” It invigorated all of us, and everybody was just producing like crazy. It seemed like every meeting we had, someone showed up with a new comic and everybody was improving by leaps and bounds.

GROTH: Did you publish the first issue of Girlhero with the Xeric Grant?

KELSO: Yeah, and I had money left over so I published the second issue with that money. By that point, I would be able to make enough money to print the next issue.

GROTH: Tell me how you went about teaming to self-publish: how you went about formulating the first issue, and putting it out.

KELSO: To get the grant, I had the entire issue as my proposal for the grant, the entire issue penciled and about half of it inked. The second story I had actually written about a year earlier as a short story, and decided to turn it into a comic, and that’s how I started doing my early comics. Except for “Bottlecap,” really, I would write out all of the stories, then convert them to comics.

GROTH: So you literally wrote them in prose first.

KELSO: So I knew from the get-go what would be the contents of the issue, but as far as the cover, the printing, Diamond, Capital and all that, it was just a matter of talking to everybody, and my friend Jon Snyder (the boyfriend from college) who wanted to get me to do comics —

GROTH: Ah-HA!

KELSO: Well, he wasn’t my boyfriend any more, but he was doing this Star Wars fanzine called Report from the Star Wars Generation, so he was dealing with printers and Diamond and Capital. He knew all of this stuff about publishing, so I got a lot of information from him. He sent me to Port [Publications], this printer, and [pointing to a Girlhero #1’s cover] I was still very attached to photography. I still didn’t want it to look like a comic book.

GROTH: Well, you more or less succeeded. [Laughter.]

KELSO: Yeah. I got in on the tail end of when everything was pretty rosy in the industry. I had no problem being listed by Diamond, Capital and the smaller distributors. I didn’t get fabulous orders, but I knew I was going to make enough money to fund the next issue.

GROTH: What kind of orders did you get? Do you remember?

KELSO: Well, I did six issues, and I never got more orders than 1,000. I don’t even think I got to 1,000. I was always hovering... orders for #1 were at 850, then they went down like they always do, then they went back up again. I was always hovering between 800 and 1,000.

GROTH: Well, that’s not bad.

KELSO: And then, you know, all hell broke loose. Capital and all the other distributors went away, the whole thing was so depressing... I think I self-published for longer than any of the other boys who got Xeric Grants...

GROTH: You probably did.

KELSO: But by the end I was just so over it.

GROTH: What did you find unpalatable about self-publishing?

KELSO: It makes me feel kind of schizophrenic: you have to be doing your comics and be all artistic on one hand, and then a hard-assed business person on the other, because they all want to fuck you. They don’t want to pay you, and you deal with printers who mess up your cover or whatever and they don’t want to admit it, you just have to be a hardass with everybody. Well, I’m sure you know that.

GROTH: Of course.

KELSO: And then you have to exert all this energy trying to promote yourself, which I never had any energy to do. I mean, I had all these great ideas, and I never did any of them, because I just didn’t have any energy left for it.

GROTH: Were you a good hardass?

KELSO: Yeah! I have a job where I have to be a hardass, but I actually think I learned to be a hardass from self-publishing.

GROTH: What is this job where you have to be a hardass?

KELSO: Well, it’s only recently, really, that I’ve had to be a hardass. They have an art collection that they exhibit at SeaTac airport, and for years I’ve been the maintenance person, cleaning the art, installing exhibits, stuff like that. Recently I’ve been scheduling, coordinating who’s going to be exhibiting, moving art around, so I’m not just the janitor any more. I’ve been there for about six years.

GROTH: Really?

KELSO: Yeah. It’s a part-time job, it pays really well, really flexible hours, they know that I’m a cartoonist and that they’re not my priority [laughs], so they’re very supportive,

GROTH: You told me you’d go over to Jason’s house and work together. How would you work together?

KELSO: Well, he was working on Jar of Fools and I was working on “Bottlecap” or “Frozen Angel.” I’m sure I asked him questions about certain things I was having trouble drawing or figuring out... I remember asking him simple things, like “How much space do you put between your panels?” and what kind of equipment he used, oh, and I totally learned... when you draw something on tracing paper, then flip it over and redraw it, then transfer it over on to Bristol board. I learned that from Jason. So, I would say my whole process of how I did my comics I picked up from watching how Jason did it.

GROTH: Do you still use that technique of drawing on tracing paper and transferring it to Bristol board?

KELSO: Yes, but not for everything. I’m trying to loosen up.

GROTH: Now, when you guys got together —you and Ed, Tom, Jon, Dave and Jason — what kind of discussions would you have?

KELSO: We talked a lot about the comics that were coming out at the time. We were all really into minicomics and had this somewhat idealistic view that the minis, the labors of love, were where it was really happening. All of us shared a real passion for the storytelling part of comics and that the art had to serve the story. I think all of us, with the exception of Jason, struggled with the drawing more than the writing. I feel a little weird speaking for all of them, but it did seem like we shared that.

GROTH: When you say that you struggled more with the drawing than the writing, does that mean that the writing came naturally, or that you preferred it to the drawing.

KELSO: Well, nothing comes naturally. I know for myself, the writing always seems easier. I think that I spend more time worrying about and working on the art; I’m actually much more disciplined trying to improve myself with the art than I am with the writing. I sort of take the writing for granted. I felt like I shared with all those people a constant struggle to figure out how to tell the story in comics, you know, the old 11th-grade English class mantra: “Show, don’t tell.” Don’t over-narrate or over-explain.

We talked about comics a lot. Naturally, a lot of it was pretty negative, what was badly done in other people’s comics, what to avoid. I listened to the guys analyze and argue about why some comics worked and others didn’t. Then they’d start talking about old guys like Kirby and that guy who did Spider-man and then went crazy — Ditko? — and I’d kind of zone out since I hadn’t read their comics. I did a lot of learning by osmosis.

GROTH: One thing that’s funny, considering that you knew so little about comics, is your use of the traditional comics elements in the first couple Girlheros. How did you get the superhero connection? It seems completely incongruous with your recent work.

KELSO: I had this epic — this science-fiction, post-apocalyptic, feminist epic — to tell. I’d like to say that I thought, “Well, it had to have superhero elements to it,” since it’s a comic, but really that’s a lie, because I knew that there were plenty of comics without superheroes. At the time, I’d still on some level found the idea really compelling, the superhero idea — what would superhero girls be like, how would they be different? I guess I thought that this was a really original idea I was pursuing. So, I would say it’s just extreme ignorance about how people had already been deconstructing superheroes and that it had been pretty much taken it as far as it could go. Just my extreme ignorance in thinking I had something new to offer in that area.

GROTH: Where do paper dolls come from? I believe you thanked Trina [Robbins] for helping you with them.

KELSO: I totally got the idea from Trina. I saw her speak at San Diego [Comic-Con], and she was talking about how a lot of women cartoonists had first been fashion illustrators, so they did these paper dolls. I’d attempted paper dolls at various times throughout my life. I’d been into paper dolls on my own, but hadn’t thought of them in years. They struck a chord. I got legions of these paper doll fans, old ladies from somewhere in Pennsylvania trying to order my comic and order my paper dolls. But then they lost interest in me because I didn’t continue to do paper dolls.

GROTH: You’ve actually had more co-writers than most cartoonists of your age and tradition. Some of the first book was co-written by someone named Joe Ennis; Jon Snyder (who we later learned was your ex-boyfriend at the time) co-wrote some “Bottlecap” —

KELSO: Well... I would say that Joe and I definitely co-wrote “Non-Biodegradable Youth,” but not as a comic. Jon worked out more as an editor. I would send him a script and he would give me suggestions, I wouldn’t say that he co-wrote it. I’m not diminishing his involvement, he was a very involved editor. And then my father, he totally wrote the story [“Reunion”], but I made it into a comic. It was totally his story.

GROTH: Did he write it out in prose?

KELSO: Like a screenplay. I remember back from when I was a kid he had these fantasies about being a screenwriter, he had even checked a couple books out of the library on how to write screenplays. I knew if I asked him to write a screenplay, concentrate on the dialogue, he’d know what to do.

GROTH: So he wrote this specifically for you?

KELSO: I asked him to.

GROTH: Really? You knew about the story and asked him, or did you just ask him to write a story?

KELSO: You know, for years I’ve been after him to write me a story. I think he’s a good storyteller. But honestly, I just thought he’d write some mellow story about growing up in Ellensburg in the ’50s, I didn’t think it was going to be a monumental sexual coming-of-age story about this event in his young life. When he came to me with it I was really taken aback... I didn’t know if I could do this, it just seemed so heavy-duty.

GROTH: [Laughing.] It’s your Maus.

KELSO: I, uh — yeah, I was a little overwhelmed. I remember going to him, and saying, “Look, I really need you to just give me the story to do whatever I want with. I told him I had to make it much shorter, and switch things... there were things in there that wouldn’t work in a comic. He looked at me and said, “It’s yours. Do whatever you want,” So maybe he was easier to work with than Spiegelman’s dad.

GROTH: Since we’re talking about your dad’s story, I wanted to ask how precise his directions were as far as how you broke it down into panels.

KELSO: He wrote it as a screenplay. He just wrote dialogue, didn’t describe anything. For some of it I went back to him and asked, “Could you tell me what this looked like?” But for a lot of it I just made it up — for the Ellensburg stuff, I’d been there, so I just sort of made it up on my own. He didn’t describe panels or images or anything.

GROTH: Did you find that in a way helpful, though? Did it give you freedom to break it down?

KELSO: Actually, based on that experience, when I did Lost Valley, the environmental comic, I told the writer, “I don’t want you to tell me,” because he reads comics, and he had this idea that he was going to write “Panel one: blah blah blah.” And I said, “I am not going to work on this if l have to go by your panel descriptions. I just want you to write it, and I’ll figure out how to turn it into a comic.” Yeah, so I think my dad and I think that was a good decision. But really, that’s the only way I’d work with someone else’s material. It’s funny, because I’ve found that it’s fully as much work using someone else’s script as using your own. Even though I do tend to write out my own stories first, I’m picturing the whole thing, and I will write in notes about really vivid images that I have. So you get a story that somebody else has written, and you don’t have any of that work done. And it made me realize how much work I’m doing visually, even though what I think I’m doing is writing.

And so when I got my dad’s story I had nothing, I felt like I was just starting completely at square one. But on the other hand, I can’t imagine having to draw a comic where the writer was telling me about panels. It makes me really mad to even say it.

GROTH: That’s interesting, because one of my few theories about comics is that the writing really is part of the drawing, and the drawing is part of the writing.

KELSO: Absolutely.

GROTH: The two should really be indistinguishable.

KELSO: Yeah. And, that’s weird, too, when people tell you “You’re such a good writer,” after reading your comic. What did they mean? Are they just talking about the panels where there’s word balloons? Because the silent panels are just as written as the others.

GROTH: I think probably it’s just a shorthand for how the story is told. They’re probably combining every element without really being aware of it.

KELSO: Yeah, I really do agree with you. I write it out first mainly because I learned to write before I learned to draw, and that’s more comfortable.

GROTH: It seems like a flaw when you can tell that comic is “written” as you’re reading it, as you’re passing over the images. I think that’s why the best comics are always written and drawn by one person.

KELSO: Although I’ve got to say that the two experiences I’ve had drawing someone else’s written story, I feel like I’ve learned more about comics, and how to make comics, than doing my own. It’s easier to see how the whole process works. I would totally do it again under the right circumstances, but I guess I kind of agree with you, in terms of the final product, probably the finest work is going to be the one person doing the whole thing. But I definitely think there’s a place for having it split up.

GROTH: Now, the two examples of your drawing from someone else’s scripts: your father’s —

KELSO: And this environmental comic, Lost Valley.

GROTH: I want to talk about that later. Whew! That took me all night to read.

KELSO: [Giggles.] You’re probably the only person I know who’s read it all.

GROTH: That was definitely written. [Kelso giggles.] I didn’t envy you drawing that, actually.

KELSO: I learned a lot.

GROTH: Yeah, I bet. I bet. Just the sheer mechanics of it?

KELSO: God, we can talk about it later, but...

GROTH: Yeah. When I read Queen of the Black Black, that was my first real experience with your work. I might have seen Girlhero, I think the serial “Bottlecap” overwhelmed me, and I put it down. When I went back and read all of the Girlhero, in succession, I discovered a clear progression in your work, in its proficiency and sophistication, and I was wondering if you could talk a little about that, specifically the six issues as a learning experience.

KELSO: [Pause.] Um... Could you prompt me?

GROTH: Sure. I’ll ask you a specific question: Correct me if I’m wrong, but there were several strips in the book collection that weren’t in Girlhero.

KELSO: “Queen,” and “The Daddy Mask.” Oh... some from other anthologies.

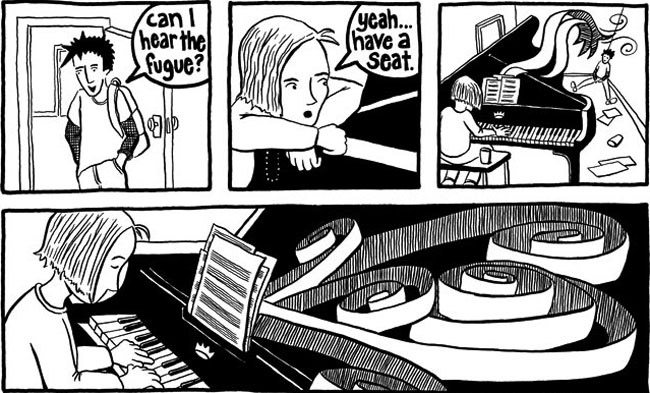

GROTH: I thought ‘The Daddy Mask” and “Composition’ were interesting, because they both tried to depict music on the printed page.

KELSO: Mmm-hmm.

GROTH: And I thought “The Daddy Mask” was a much better, more refined piece of work. Maybe I’m digging myself into a hole here, but was that done after “Composition?”

KELSO: Mm-hmm.

GROTH: That’s good. It seemed like you learned something from doing “Composition.”

KELSO: Glad to hear it.

GROTH: I’m relieved to hear that because if you did “Composition” afterward, that would be a real setback for you —you’d have unlearned something. But it seemed like that was a very specific instance of you having somehow learned or discovered a much more sophisticated way of depicting music, which you would not have found if you hadn’t done the first strip. It was better on every level: the drawing, the story itself. “Composition” was —I don’t know what year you did that, but it was more adolescent —

KELSO: Late ’94, early ’95.

GROTH: —And ‘Daddy Mask” was, I think, much more subtle.

KELSO: A lot transpired between those two stories.

GROTH: Good. Tell me what transpired between those two stories?

KELSO: Well, I did “Composition” probably around the time of Girlhero #4, and the story “Whistle and Queenie” for Dark Horse Presents. And I do remember a turning point while working on that story. I finally had enough mental space to sit back and think, “How do I want to construct this story?” Before that, it was such a struggle to get the story out in any form at all — it never felt like I had any choice about how to tell it. But then I was able to make decisions about things like how time would unfold, how the pacing would work, transitions. I exerted more control over the story; before it felt like the story was in charge, not me. Since “Whistle and Queenie” it’s been a progression of learning that I can calculate, plan and strategize every aspect of the comic.

As for depicting music, my idea of what I wanted didn’t really change from “Composition” to “Daddy Mask,” I just got more skills. I got the idea of showing the music as a physical manifestation from Saul Steinberg — an old New Yorker drawing.

GROTH: It’s almost as if you had to get the rudiments behind you before you could concentrate on the refinements.

KELSO: Yeah! And I used to feel trapped by my stories.

GROTH: How do you mean?

KELSO: It’s hard to describe. You’d have to get the person from point A to point B, so then you’d be stuck drawing this boring sequence, of them walking down the street or down a hall. It’s dull, hard to draw, you didn’t really want to do it, but how else was the story going to work? I know now that if I think about it long enough, I can figure out a way to make something happen that’ll be fun to draw, that I want to draw. Does that make any sense?

GROTH: Yeah, yeah.

KELSO: So, that is definitely something I was learning between those two stories. I also made my peace with word balloons and panels. I started using lots of panels, felt fine about word balloons... I still do like to take the words out of panels and stick them in the frame if it makes sense, and if there’s room for it and it’s not going to be too confusing. I still like that — one of my favorite things about comics is that where writing stops and drawing starts is blurry, and by putting the words out there in the drawing is sort of underlining that fact, and maybe in this political way, forcing the reader to not be able to separate them, and as a reader they shouldn’t separate them. I think a lot of my early comics stem from this political urge to force a sort of confrontational art approach. I realize now that it’s not always appropriate, but I still sometimes want to control how the person is going to experience the comic, throw things at them like no word balloons, or whatever.

GROTH: Were you conscious in “The Daddy Mask” of trying to create a musical rhythm to the drawing, in the sequences?

KELSO: No, not really, or not specifically that story. I am very conscious of the rhythm in all the comics I do. It’s as if I hear in my head where I want pauses, silences, how long they should last... then I have to figure out how to draw it, to get that rhythm. Depicting the actual music was a separate issue. What I really wanted were these Robert Motherwellish calligraphic slashes that would represent difficult, arty “grown-up” music that kids hate, but it was hard to do it as boldly as I wanted without overwhelming the drawing, so I don’t feel that I was completely successful. But the whole story was supposed to convey the kind of incomprehensibility of the adult world, and I don’t know if readers took the music swirls as underscoring that…

GROTH: Yes, right. But there’s a lot going on in that story. That story might be the most successful in highlighting the qualities I like most about your work, this ethereal quality where you dance around certain intangible aspects like relationships or moods and so on, and by the time you finish the story you’ve seen them or felt them, but as a very subtle kind of evocation.

Why don’t I ask you about your use of metaphor — you seem to use metaphor more convincingly than any artist of your generation. A lot of cartoonists are very literal, and I think you use metaphor more than most. “Pennyroyal Tea,” for example, and “Queen of the Black Black” moves in and out of metaphor. It was realistic when the Queen refers back to her days as a student, but is more of a fantasia in the contemporary scenes... I’m not quite sure how that works, but it does work. Can you tell me why that works, and why you chose to do that?

KELSO: I think that I’ve wanted to work that way from the very beginning. I know “Bottlecap” ultimately failed, but it started that way. I wanted to have the right to make things very fantastical when I wanted to, and very real when I wanted to, and not feel like it had to be one or the other. Most of my favorite books are that way: it’s a way of writing and storytelling that’s always really appealed to me. I like fairy tales, I like sci-fi a lot, but there seems to be this current in sci-fi (and a lot of comics, too) where you’re really worried about the rules of the world that the story is taking place in, and it all has to be continuous, and… to hell with that. Not interested. I’ve always felt like it’s my right as a storyteller to do whatever I want, really. And sometimes I’ve confused the reader, but I’d rather confuse than over-explain. To tell the stories I want to tell, I need to occasionally do things that don’t exist in the real world, that don’t work in the real world — pretend there’s nothing weird about it. If you tell the story clearly, usually the reader will know. I am one of those people who knows what they want to say; I know what I want a story to communicate. But I do a lot of planning. I don’t naturally take the intuitive approach.

GROTH: So you pretty much know what you want to express, but it’s a matter of getting there.

KELSO: Recently I’ve been trying to be a little more loose. When I did that minicomic last summer, I didn’t know what the hell that was, I really didn’t have a plan.

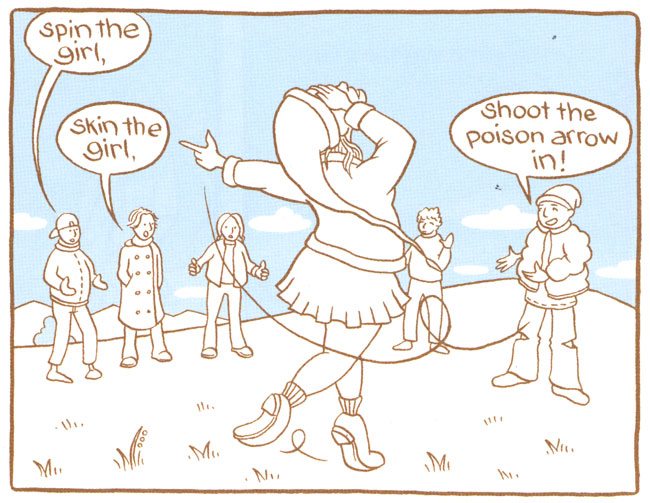

GROTH: Well, since you know what you want to do before you do a story, tell me: the minicomic you refer to is Split Rock, Montana, and there are two versions of this. I don’t see why there are two versions; frankly I prefer the minicomic version to the one-page strip. Can you tell me what you were trying to convey in this story? It’s ambiguous.

KELSO: I wanted to do one of those comics that everyone seems to do eventually where the words and the pictures really have no relation to each other, but by putting them together they become related. And that’s where I started. I had this, um... well, it wasn’t really a dream, it was more of a fantasy, and it was the image of all these boys standing in a circle in a field, and me in the middle of the circle, so I just drew the images. I didn’t think too much about what it all meant. I just decided to do this exercise — and this was definitely an exercise. Then I decided to just write based on a general feeling I had about these images, but not trying to explain them, per se. In the process of putting them together, I came up with a narrative in spite of myself, though I tried to keep it oblique. I think it’s about desire: being desired, and that sort of creepy place where you have sexual fantasies about things you would never want to happen in real life, but you make happen anyway.

GROTH: Hence the fellatio.

KELSO: I... I like to draw blowjobs.

GROTH: You do? I haven’t noticed that.

KELSO: You know, I have drawn lots of other blowjobs.

GROTH: Really, where? I thought I looked at your entire oeuvre. I notice blowjobs.

KELSO: I just said that as a joke because my friend Jef Czekaj read Lost Valley and—

GROTH: Definitely not a blowjob in that comic.

KELSO: —and he said to someone else, “So where’s the blowjob? It’s a Megan comic, where’s the blowjob?” Here’s another...

GROTH: Right, there’s that one. That’s two...

KELSO: Oh, but there’s — [produces comic] a total of four, I think.

GROTH: Oh yes. I think I should make this a facet of all my interviews. Demand to know how many blowjobs the artist has drawn. I just interviewed John Severin, and I don’t think he’d ever drawn one. The blowjob in Split Rock, Montana was a little startling, just because of the context. It was unexpected.

KELSO: Yeah? You didn’t think it was going to be a sex game?

GROTH: I didn’t think it was going to be as explicit or literal.

KELSO: But you were expecting some sort of sexual something.

GROTH: Yeah, I could see sexual metaphors rolling through the strip.

KELSO: Well, when I worked with my friend Virginia (who’s sort of my editor now), we talked about that, should I actually show the blowjob? See, the more literal story here is this somewhat unattractive girl in this exploitative situation, yet she’s willingly doing it. And in that story, the ugly girl would in fact give the guy the blowjob, so I didn’t want to leave that ambiguous.

GROTH: Yeah, I didn’t think it was a mistake, but—

KELSO: It was startling?

GROTH: It was precisely because it was startling that I thought it worked. Let’s see, where can I go from blowjobs? I wanted to ask you specific questions about some strips.

KELSO: OK.