This is the second of two columns I've written about the cartoonist Gus Mager (1878-1956). My previous column provided an overview of Mager's cartooning career. Now, we wind the clock back to 1904 and take a look at what could be called the "lost" Sundays of Gus Mager - three short series that represent fascinating experiments in style and content.

This is the second of two columns I've written about the cartoonist Gus Mager (1878-1956). My previous column provided an overview of Mager's cartooning career. Now, we wind the clock back to 1904 and take a look at what could be called the "lost" Sundays of Gus Mager - three short series that represent fascinating experiments in style and content.

Charles A. Mager: Painter and Fine Artist

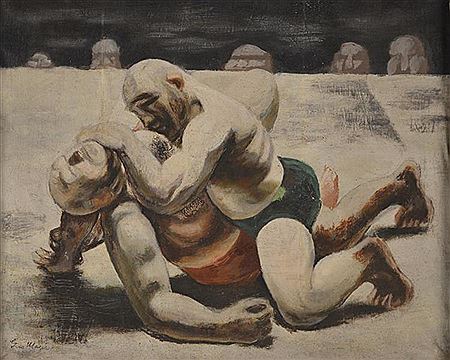

As has previously been mentioned, in addition to his popular comic strips, Mager enjoyed success as a painter. His specialty was flowers (as I write this there is a flower painting attributed to Mager on Ebay with a starting bid of $450). Mager had some flower paintings in the landmark 1913 New York Armory Show (along with paintings by his friend and fellow cartoonist Rudolph Dirks).

Though reduced to simple forms, Mager's paintings have a presence that some find appealing. The French painter, Guy Pène Du Bois (father of the great children's book author-artist, William Pène Du Bois), wrote about Mager as "one of the few 'post' modern painters whose sincerity is convincing."

Mager’s work today is part of the permanent collections of several museums that might not know anything about “Gus Mager," but may indeed recognize the name "Charles A. Mager." Gus Mager also painted some impressive works with human figures that display the same playful plasticity one finds in his comics.

Mager’s success as a painter suggests a formidable depth to his talent as an artist that extends past his popular hippos, monks and detectives, covered in my previous column.

Comics scholar and art professor Rob Stolzer has shared some rarely seen scans from a sketchbook of Mager's that he owns. When comparing Mager's fine art to his cartoons, Stolzer observes: "I think Mager's sketchbook work and paintings are pretty much apples and oranges when compared to his cartoon art. I would say the same about Rick Yager, who was a fantastic watercolorist, though his cartoon ink work didn't hold a candle to it. In Mager's case, he always had a pretty sensitive line, so maybe that's one thing that does carry over. What has always struck me most about Mager's sketches is the intimacy within some of them. The drawing of his wife, done with such few means, is simply wonderful."

Mager's general cartooning style is mostly unconcerned with painterly or fine art techniques. However, from 1904 to 1906, Mager created three offbeat Sunday comic strips which display what one might call experiments with with the form. These three "lost Sundays" are completely forgotten today, but each one is so resplendent with humor and technique that they beg to be re-discovered and appreciated.

And Then Papa Came (1904)

In September 11, 1904, Mager created the half-page And Then Papa Came, his first run at a Sunday feature. The series features his comical monk-human figures and comes before his “O” suffixed crew of neurotics (such as Henpecko, Groucho, and Rhymo) arrived on the scene a couple of years later.

The basic idea of the strip is simple. A girl's suitor hides when poppa comes, and chaos ensues when poppa comically discovers the suitor, usually in a hilariously painful way, and goes bananas. Mager's drawings are richly comical, with a clarity of composition and line that effectively puts across the humor in the situations.

In the October 9, 1904 episode, we see Mager experimenting with repetition in the background. The six circles of the moons in squares of black are a stabilizing visual element that is both decorative and has a story function, telling us it's a bright moonlit night. Another artist working in comics at this time who used background elements to heighten aesthetic value was Winsor McCay, who masterfully used a full moon in his famous “walking bed” episode of Little Nemo in Slumberland.

The next week's episode, dated October 16 -- sadly, the last in the all-too-brief series -- used small white circles representing oranges in the color field of the tree. There are fewer and fewer white circles, as the oranges fall onto the head of Papa, who is shaking the tree to flush out his daughter’s unapproved of suitor. The reduction of the fruit to white circles, all the same size, creates a beautiful device that in its simplicity that anticipates the minimal style of Otto Soglow (The Little King).

The character designs of Mager’s monkeys are compellingly ugly and funny. As his famed contemporaries Frederick Opper and James Swinnerton so often did, Mager has created a six panel sequence where the chaos explodes in the fifth panel, followed by a denouement in the sixth panel. From week-to-week, the series grows funnier as we learn to expect the final scene of the ill-fated suitor scampering towards the horizon. Mager's staging in the final panel, where we see the characters from the back and from a distance, encourages us to step back and laugh, similar to the way Carl Barks sometimes ended his 10-page Donald Duck stories in the 1940s and 1950s. Sadly, the series ended after just six episodes.

What Little Johnny Wanted (1906)

About two years after And Then Papa Came, on September 30, 1906 Gus Mager’s What Little Johnny Wanted first appeared. The comic is a sharp, satirical reversal of warm and fuzzy child-oriented fantasy adventures, and represents a far more refined and sophisticated accomplishment than anything that Mager had produced up to this point.

Running for only five consecutive Sundays, from September 30 to October 28, 1906, What Little Johnny Wanted is a pure distillation of the form, presenting in each episode the same simple sentence in large, bold letters across the tops of the panels: "What little Johnny wanted (or some variation thereof) and what he got." Wedded with a wordless graphic narrative, the sentence works beautifully, propelling the reader through the narratives. It is also a wry commentary on the nature of fantasy versus adult reality -- the two worlds that early American comic strips (and genre literature) straddle.

In the first five panels of the premier six-panel episode, Little Johnny fights and defeats a pack of tigers with a toy wooden sword and his own bare hands, to the astonishment of the adults in his life, and a nameless wide-eyed little girl. This is what he wanted to do (note the sentence for this first strip is slightly different from the following episodes). In the sixth panel, we see what he did instead, a tedious music lesson forced on him by a threatening father with a handful of switches.

In what have been conceived of as a dialogue-free reduction of The Katzenjammer Kids, Mager has captured with What Little Johnny Wanted the interior power fantasies of a young child – the raw material that would later meld into superhero comics. It was a fresh, irreverent concept. Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo dreamed of ice palaces, dancing beds and rococo architecture. Perhaps more realistically, Gus Mager’s Little Johnny dreams of slaughter, murder, and torture!

What Little Johnny Wanted, portrays children in a somewhat negative light, drawing on the Wilhelm Busch Max Und Moritz tradition, which led to the creation of the Katzenjammer Kids by Rudolph Dirks. Mager’s unabashed portrayal of children is similar to the way Roald Dahl and Maurice Sendak would famously show both the goodness and wickedness young humans are capable of creating, and excel in depicting their fantasy world. What Little Johnny Wanted, is strikingly similar to Bill Waterson’s Calvin and Hobbes, right down to the blurred lines between fantasy and reality – and there’s even tigers!

On the same Sunday the first Johnny appeared, Mager contributed the first of his brief spate of banner art drawn for other Hearst comics. Functioning as a sort of proto-topper, Mager's comic at the top of Frederick Opper’s September 30, 1906 And Her Name Was Maud is a vignette from What Little Johnny Wanted -- not lifted from any episode, but an original scene. The wide-eyed little girl who appears in Johnny’s violent fantasies appears here.

With Johnny as well as The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar, the Sunday comic that immediately followed, Mager found a way to draw his goofy jungle animals in clever new story structures. In Johnny, the animals are always part of his fantasy world, which occupies the first five of six panels. Mager's cartoons animals, both cute and wild aren't that far off from the animal-monsters in Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are (1963). In fact, Mager's Johnny and Sendak are thematically related, in that they both present an unsentimental and honest view of a child's desire for power and dominance.

While the episodes of Johnny are structurally repetitive, each strip actually explores a different angle of a child's fantasy. In the October 14, 1906 episode, Johnny is the uber-hero, effortlessly defeating buffalo, Indians, and a lion. In the end, we learn he was inspired by a dime novel adventure. Mager draws the strip in relative perspective with no background details, creating a minimalism rarely seen in comics from this period.

In the last episode of the series, Mager brings back one of the sanguine tigers from episode one. This time, instead of an enemy to defeat, the tiger is an ally -- prefiguring Calvin and Hobbes, if only for an eyeblink in comics history. Still, perhaps the greatest aspect of What Little Johnny Wanted is the celebration of the richness and sheer, delightfully snarky kid-ness of a boy's fantasy world.

Sadly, What Little Johnny Wanted ended far too soon. With this comic, Gus Mager was decades ahead of his time. Perhaps audiences of the 1900s weren't as ready to celebrate the psychotic fantasies of the common boy as they were in the 1960s with the widespread embrace of Maurice Sendak's Caldecott Medal winning Where the Wild Things Are and in the 1980s, when Calvin and Hobbes became a hit.

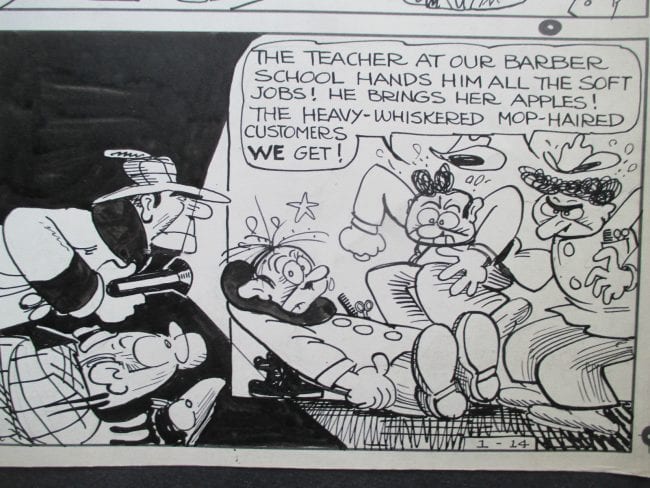

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar (1906)

After a short vacation of a week, Mager returned to the Sunday supplement with a new comic, equally formal in structure and as eccentric in concept as What Little Johnny Wanted. After his brief foray into the violent fantasies of young Johnny, Mager shifted his focus onto western culture itself, presenting the disastrous adventures of a full grown, fussy American salesman attempting to peddle the wondrous goods of his civilized world to the African inhabitants of a less technological society. Of course, nothing goes as the American salesman expects.

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar ran from November 11 to December 16 in 1906. In the first episode, Pete has rowed ashore from his big, two-masted ship, visible on the horizon. He is greeted on the beach by a grinning giraffe, a leering hippo, a curious ostrich, and jungle natives who are oblivious to both the process of a proper sales transaction and the intended use of the products Pete peddles. By the end of the first adventure, the drooling hippo, a sort of uber-consumer, attempts to consume Pete's wares and also the "pedlar" himself!

The odd, otherworldly scenario Mager created in The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar, resonates with “Sail Away,” a 1972 song written and performed by Randy Newman. In Newman’s song, a slave trader arrives on the shores of an African village and woos the natives with promises of a better life if they will only come with him: “In America you’ll get food to eat/won’t have to run through the jungle and scuff up your feet… ain’t no lions or tigers/ain’t no mamba snake/just the sweet watermelon and the buckwheat cake.”

Of course, everything the slave trader is saying to the natives is a lie. These lyrics are bathed in a beautiful, soaring score that belies the savage truth. In Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’Roll Music, Greil Marcus writes about Newman’s song: “This peaceful, quiet song is more outrageous than anything the Rolling Stones have ever done…”

Similarly, Mager's Pete is on the surface a funny little screwball comic that perhaps cloaks an outrageous jab at American culture. A clue to this can be found in the name of Pete's company: Joblot and Bunkum ("bunk" is slang for false information). Mager is also drawing dark-skinned aboriginal people in the same way that black Americans were most often represented in American newspaper comics of the time, with large lips and bulging eyes. Instead of making the black people the butts of the gags, Mager’s Pete comics point to the falseness of the salesman’s assumptions, and he becomes the inept, foolish, and laughable figure. Even Mager’s “monks” appear to be an inversion of the racial stereotyping prevalent in American newspaper comics of the first half of the twentieth century.

Even though the machine-made goods Pete sells are functional, the ritual of the sales pitch always devolves into chaos for him and his potential customers. A hippo eats a record player and chases Pete, with a song streaming from his open mouth – this seems to inhabit a more poetic and beautifully surreal space than the simple pranks of the smirking Katzenjammer Kids, or the earthbound mischief of the eternally repentant Buster Brown.

In late 1906 and early 1907, Gus Mager was at a crossroads. He could continue to develop his charming, artful and pointedly satirical Sunday comics or he could devote his attention to the Monks series, which was starting to climb the tree of success. He chose the latter. It appears that, except for a few pieces of banner art for other strips, Mager abandoned his innovative formalist/minimalist cartooning style and approach, although traces of it continued to appear in his Sherlocko/Hawkshaw comics.

Gus Mager's innovative early Sunday comics are among hundreds of such experiments made with comics in the freewheeling days of early American newspaper comics. From the vantage point of more than a century later, we can see that Mager was on to something, creating an early version of a visual storytelling style that would emerge into the mainstream of American culture some forty or fifty years later with comics like Crockett Johnson's Barnaby and the UPA animation studio's celebrated stylized cartoons.

Gus Mager’s life and work bears further scrutiny. In 1906, he was on the trail of a new style of visual storytelling. These comics embraced minimalism and other formal art elements to offer a simple but profound graphic style. The writing of the comics took on the form of simple gag strips but also poked at the soft underbelly of American cultural beliefs and the startling idea of showing a child's fantasy life, violent and funny, intermixed with reality.

Mager, like most American cartoonists of the early 20th century, was first and foremost a popular artist who reshaped his vision and style until he hit upon something that pleased the general public. In doing so, he left behind his bold 1904-1906 experiments in comics, which have since been consigned to the dustbins of history. Even so, much of his work before, during, and after the period of the "lost Sundays" bears the stamp of a quirky, gifted artist and is worth further study and appreciation.

+++++++

Paul Tumey is a writer, artist, and designer who lives in Seattle, Washington. He has run his own presentation design business, Presentation Tree, since 1999. His comics history work appears in THE ART OF RUBE GOLDBERG (Abrams ComicArts, 2013), which he also co-edited. He also wrote the introduction to THE BUNGLE FAMILY 1930 (IDW, 2014). He contributed an essay to SOCIETY IS NIX (Sunday Press, 2013), and was also a contributing editor, researching and writing mini-bios of over 50 obscure cartoonists. Most recently, he served as an essayist and associate editor of IDW’s KING OF THE COMICS: ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF KING FEATURES SYNDICATE. He writes a regular column called FRAMED! for The Comics Journal at www.tcj.com. He is currently at work writing a book about the great American screwball cartoonists, which will include Gus Mager.

All contents © 2016 Paul C. Tumey