1938 was the year that Superman appeared. It was also the year that Jack Cole became a comic book artist.

1938 was the year that Superman appeared. It was also the year that Jack Cole became a comic book artist.

Welcome to part two of my continuing survey of the lesser known (and, in some cases, virtually unknown) comics of Jack Cole.

For part one of this series, see this earlier Framed! column, here. This time, we look at Jack Cole's first year of comic book work from roughly 1938, done while he worked at the Harry "A" Chesler shop from late 1937 (or early 1938) to sometime in the winter of 1940.

Very little has been written about this period of Cole's work. In part this has been due to the fact that the comic books that originally published his early work are hard to find and expensive to acquire. However, with the recent development of some generous collectors (bless 'em all!) sharing digital scans of these rare comics, it has become possible -- with some effort -- to mine a rich vein of Jack Cole's early work.

It has also been difficult to write authoritatively about Jack Cole's early comic book work because it is often misidentified. In various databases and references, including The Grand Comics Database, and Overstreet's Comic Book Price Guide, work done by other artists is credited to Cole, while other pages by Cole are not identified as such. In the midst of this confusion, it has been challenging to develop any deeper historical and aesthetic understanding of Jack Cole's early comic book work.

After years of work, I am pleased to present in this article the first steps toward a serious consideration of the early comic book work of Jack Cole. Much of the examples covered in this article are pages that have been lost to Cole fans for decades.

It is worthwhile to study Cole's pre-superhero work of 1938-1940 because this work contains distinctly separate and evolving strains of light-hearted comedy and grim noir that Cole would later brilliantly combine into his Plastic Man stories, his primary artistic achievement. Cole began his comics career by enthusiastically throwing himself into creating for magazines and comic books the sort of screwball comics that newspaper masters like Rube Goldberg, Milt Gross, Bill Holman, and Gene Ahern had crafted. A survey of this work alone reveals Jack Cole's talent and intelligence. After a year at the Chesler shop, however, Cole began to develop longer, more serious crime stories. These stories, particularly his first non-humorous story, "Little Dynamite" are as dark and disturbing as his humor comics are wildly zany.

It was likely through a combination of economic necessity and market demand that Cole allowed the shadow aspect of himself to emerge into his work. The greatness of Cole's best work offers a unique and inventive combination of what may be called the light and dark sides of human nature. His Plastic Man stories represent a brilliant recasting of super-hero, crime, adventure, science fiction, romance, and western stories as streamlined screwball sagas - a pliable mix of slapstick comedy and superhero seriousness. We can more readily understand and appreciate Cole's accomplishment with his later comic book work when we study his rapid development from 1938-1940.

Put Another Way:

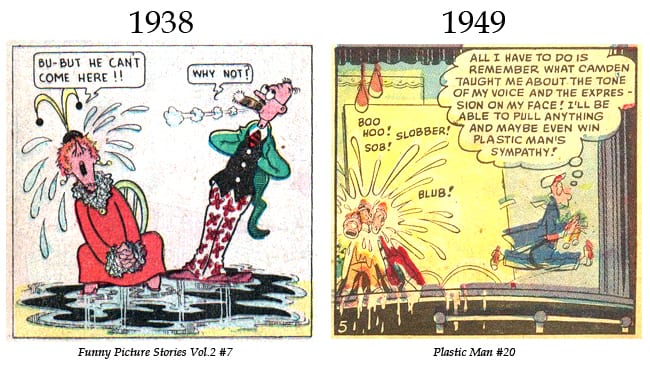

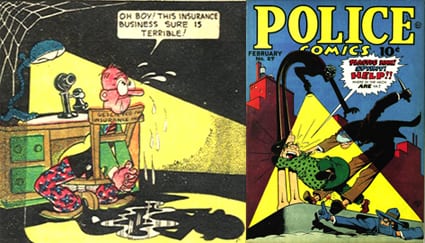

This is about how, in two year's time, Jack Cole stretched from this:

to this:

Reaching For the Stars While Standing In Quick Sand (1937)

Jack Cole was a child of the Depression.

In 1929, when he was 14 years old, the United States economy collapsed, sending the country into a desperate struggle to survive for several years thereafter. By 1932, the average hourly wage in the United States had plummeted by sixty percent. Millions were unemployed. The Coles, a family of seven living on one income, seem to have done better than many -- but there is no doubt they struggled to make it through the hard times, just like many Americans in the 1930s.

Jack Cole came of age in a world where a dollar was hard to come by. Somehow, Jack’s father, DeLace, managed to navigate his family through the hard times as he worked as a manager at a dry goods store. When Jack asked for money to finance correspondence art school lessons, his father had to say no. When Jack rode his bike across the country to see the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, he couldn’t afford a ticket to the event. Small wonder, then, that Cole seemed to possess an innate sense of absurdity.

When a colleague and friend of Cole’s, Gill Fox (a fellow bullpen artist at the Chelser Shop and later Cole’s editor at Quality), was asked why he got into cartooning, he replied: “It was survival. I come from the depths of the Depression. I knew the way it was going I’d be driving a truck. I had to make a positive decision, and it seemed to me that cartooning would be a way out.” (Jim Amash interview with Gill Fox, Alter Ego #12, January 2002)

________________________________________

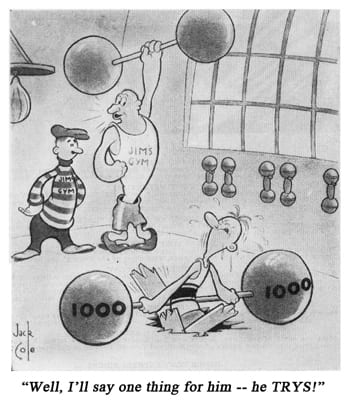

Cole's gag panel cartoon published in the July, 1938 issue of Boy's Life may have been inspired by the fact that he was also struggling with the dead-weight of lifting an artistic career. He was indeed trying hard, but as his cartoon shows, it was starting to look futile. Note also Cole's brief 1938 flirtation with Popeye-style arms. Popeye's creator, E.C. Segar, was an inspiration and influence on Cole. Segar died in October of 1938.

Cole's gag panel cartoon published in the July, 1938 issue of Boy's Life may have been inspired by the fact that he was also struggling with the dead-weight of lifting an artistic career. He was indeed trying hard, but as his cartoon shows, it was starting to look futile. Note also Cole's brief 1938 flirtation with Popeye-style arms. Popeye's creator, E.C. Segar, was an inspiration and influence on Cole. Segar died in October of 1938.

________________________________________

In the fall of 1937, young Cole was living on West 14th Street in Manhattan with his equally young wife, pursuing his dream of becoming a professional cartoonist – and starving. The income from his few sales of gag panel cartoons to magazines was far below what he and his wife needed to survive. Cole was successful in breaking in -- selling to impressive, big-name, top-paying markets, but his career was developing far too slowly. He had run out of the money he borrowed from merchants and friends in his hometown. For a young man who had just lived through the Great Depression, his hope-filled lunge towards his dream must have felt like reaching for the stars while standing in quicksand.

If young Jack Ralph failed, it was back to New Castle, probably back to living with his in-laws and working at a factory. Articles had been written about him in the home town paper, talking about his success and telling how the famous columnist Walter Winchell had said great things about the boy from New Castle. How could Cole retreat from New York, face the set-back of his dream, and be happy?

But, of course, Jack Cole didn’t fail.

Instead, Jack Cole and comic books found each other.

The Chesler Match

As he was making his regular rounds in 1937 to the offices of various New York magazine publishers, selling a few cartoons here and there, Jack Cole may have begun to realize he needed to widen his scope in order to make it as a cartoonist. Fortunately for Cole, he was in the right place at the right time. A massive new market for cartoonists was opening up – the comic book. Originally a re-formatted book-like pamphlet reprinting of Sunday newspaper comics, the success of the idea generated such a growing demand that savvy entrepreneurs began to supply comic book publishers with original material.

One of these entrepreneurs was Harry “A” Chesler. His quirky, quotation-framed middle initial was an affectation, designed to make him sound more important. It’s said that Chelser sometimes told people the “A” stood for “Anything.” In 1935 or 1936, Chelser began congregating artists and writers into rented studio spaces and paying them small amounts of money to create material that he could then sell to comic book publishers, including Centaur, MLJ (later known as Archie Comics), Street and Smith, Fox and Fawcett. Some of the writers and artists who worked in the Chelser shops at one time or another went on to become legends in comics: Jack Binder (who later opened up his own shop), Otto Binder, Charles Biro, Carl Burgos, Lou Fine, Creig Flessel, Gill Fox, Fred Guardineer, Paul Gustavson, Carmine Infantino, Joe Kubert, Roy Krenkel, Mort Meskin, Mac Raboy, George Tuska, Bob Wood, and – of course – Jack Cole.

Born in New Jersey and raised in East Orange, Chesler was a sharply dressed hustler who appears to have been drawn to the business of creating sequential graphic narratives purely for the business opportunity, rather than an initial appreciation for art (although later in life, Chesler built a vast library on comics and illustration art – see Framed!Works, below). Wikipedia’s scrupulously annotated entry on Chesler currently states that he sold furniture, worked for the Philadelphia Public Ledger, and sold advertising. Artist Gill Fox remembered that Chesler would “come in wearing a hat on the back of his head with a watch chain in his vest. He reminded me of a fight promoter, and he smoked a cigar.” (Jim Amash interview with Gill Fox, Alter Ego #12, January 2002)

When asked if Chelser provided any of the art direction for the comics he packaged and sold, artist George Tuska said, “No. Chesler didn’t know anything about art. He was in the furniture business before he went into comics. He sold furniture. He did alright with comics. Bought a lot of property in Jersey. Made his own lake.” (The Art of George Tuska by Dewey Cassell, TwoMorrows Publishing, 2005)

It’s possible that Jack Cole found his way to Chesler by responding to an ad in the paper, the way several other artists wound up working there. The golden age comic book journeyman artist Fred Guardineer, like Cole, had moved to Manhattan as a young man hoping to jump-start his career. As with Cole, he reached a point of desperation. Guardineer wrote, “In November of 1936, weary of pounding pavements, and ready to give it up, I took one last crack at a New York Times ad and was hired to draw pages for comic books being brought out by Harry “A” Chesler. It was twenty bucks a week… by February of 1938, I was making thirty dollars a week, had a bank account and hosted a few parties they still talk about…” (The Steranko History of Comics, Volume Two by James Sternako, Supergraphics, 1972)

Gill Fox also mentioned a New York Times ad when he recounted his story about joining the Chelser shop to Jim Amash: “Harry “A” Chesler placed an ad in The New York Times or somewhere, looking for artists for his studio. I went over there and he said. ‘Do four samples.’ I went home and did them in a week or so and brought them in. He said, ‘These are fine. I can use them. How would you like a job?’ I asked how much, and he said $20 a week. ” (Jim Amash interview with Gill Fox, Alter Ego #12, January 2002)

Accounts like Guardineer’s, Tuska’s, and Fox’s are important because, in the absence of any interview material with Jack Cole, we can look to the similar experiences of his colleagues to get a sense of what it was like for the 22-year old cartoonist to connect with and work at the Harry “A” Chesler shop.

Although we don’t know for sure, it seems likely that Jack Cole joined the Chesler shop in a similar manner as Guardineer, Tuska, and Fox. He probably spotted one of Chesler's ads recruiting creatives for his publishing venture and went to the studio located between Sixth and Seventh Avenues on West 23rd Avenue, some 10 or 15 blocks from where he was living. It seems probable that Cole showed Chesler his few published magazine gag panel cartoons and was asked to work up samples (by the way, Fox was never paid for the four samples he gave Chelser, who later published them, which suggests something about what it was like to deal with Chesler). In his 1956 Freelancer article, Jack Cole wrote that Chesler started him out at $20 a week. This was not great – but decent money at the time – certainly it represented a meaningful income for a starving artist. Gill Fox said that, when Chesler offered him $20 a week, “My nose started bleeding – no kidding, standing right there in front of his desk… my father was a milkman and he got $35 a week.”

As far we currently know, Cole’s first published pages for Chesler appeared in comics with a cover date of March, 1938. There was a difference of three to four months between the time artwork was finished and the time it appeared in a comic book on the newsstands. This suggests that Jack Cole may have joined the Harry "A" Chelser shop in late 1937 or early 1938.

Around this time, Cole's life must have changed. Up to this point, his life in New York probably consisted of daily toil at the drawing board at his Greenwich Village apartment mixed with weekly forays into the teeming streets of New York City where he attempted to sell his work to magazine editors. Now, forced to take a steady job by dire circumstances, Cole reported to work every day to the Harry "A" Chesler shop on West 23rd Avenue, located between Sixth and Seventh Avenue. It's likely that he was still putting in some time at night drawing cartoons for magazines, as well, since he continued to sell to magazines during 1938-1940.

In a Comics Journal interview with Gary Groth, Chesler Shop alumni and comics legend Carmine Infantino described the "old broken-down warehouse" that housed the Harry Chesler shop during the time of Cole's employment:

"It was an old factory building, and there was this broken elevator, and it rattled its way up to about the fourth floor — it was a five-story building. And as you got off the elevator, you faced a brick wall. In front of the brick wall was Harry Chesler sitting with his cigar in front of an old, broken-down desk, puffing away. A Milt Caniff Terry original hung on the wall behind him. That was one room. Then when you went in to your right there was a larger room where about five or six artists and letterers sat, and did their artwork. That was it. But they worked most of the day, they didn’t talk much. They rarely kidded around, not that much, because Harry would be sitting out there watching everybody, and puffing his nickel cigars." (Carmine Infantino Interview by Gary Groth, The Comics Journal 191, https://www.tcj.com/the-carmine-infantino-interview/)

Based on digital Chesler material that is currently in circulation, we know that Jack Cole wrote and drew at least 138 pages of comics and four covers while at the Chesler shop. There could well be more waiting to be discovered. It appears that Cole's work for the Harry Chesler Shop ran in comics published by Centaur, MLJ/Archie, Nedor/Better/Standard, Novelty Press and Hillman.

As far as is currently known, it appears that Jack Cole left the Chesler Shop in late 1939 or early 1940 to work for publisher Lev Gleason as the editor of his new Silver Streak comic book (named after Gleason's new car).

Front and Centaur

All of Cole’s Chesler work published in 1938 appeared in various anthology comics published by Centaur and packaged entirely by Harry Chesler. These 64-pages long comics are composed of various random original features that range from one page in length to six. In 1938 there was no flagship strip or continuing star character. In this brief pre-Superman era of comic book publishing, the basic model was still the newspaper Sunday comic supplements, which offered an assortment of short features. In fact, it seems that many of the early publishers of comic books viewed them as a potential path into the more lucrative newspaper comics field. Chelser developed several of his early comic features such as Fred Guardineer's Dan Hastings into comic strip format, which he marketed to the newspaper syndicates.

Thus, the 1938 Centaur comics were sausage comics – all mixed filler. This varied format allowed a lot of different artists with different styles to try out different things. It especially allowed a young cartoonist like Cole to experiment and develop his chops, an opportunity Cole appears to have relished.

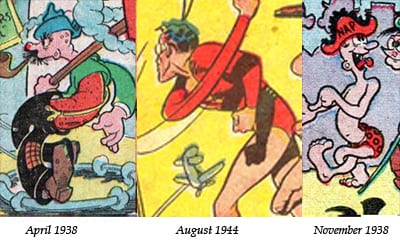

It's also important to note that the order in which the Chelser material was published does not necessarily match the order in which it was created. For example, there's "Down the Trail," the wonderful Jack Cole one-pager devoted to gag panels about trailers on road trips that ran in a Chesler comic dated July, 1944 (Punch #9). Cole left the Chesler shop in late 1940, so this page is either a reprint, or a first printing of artwork done well before 1944. The art style of the page dates it from 1938, when Cole was drawing his "puppet-like" figures with large, "Popeye" style forearms.

Chesler ran his shop by assembling a stable of writers and artists who came to work each day and produced saleable content. Since Chesler was assembling packages of comics for other publishers, it's likely that some material was stockpiled as "inventory" for later use. Other material may have been rejected by clients and also filed for possible later use.

Because there is no record of what was actually created when, it is not possible to examine Cole's work for the Chesler shop with chronological precision. Given this, a study of the notable aspects and common characteristics of the 1938-39, rather than by a guessed order of creation is the most helpful approach to consider this period of Cole's work. Some of these common characteristics are: Cole's use of gag panels, his early efforts to translate the screwball form into comic books, and the first appearance of styles and techniques that developed into elements of his mature work on Plastic Man.

Gag Order

Several of Jack Cole's Chesler pages are collections of one-panel gags, rather than sequential narratives. These gags appear to be no different than the work Cole was placing in Boy’s Life and Judge, and are probably spill-overs from his months of developing such gags to sell to magazines. The page below, “Belly Laughs,” is from Star Comics Volume 1, Number 11 (April, 1938).

Cole’s signature at the bottom right resembles the same signature he used for his Boy’s Life cartoons of the same period. Note that another hand has added “+ Nagle,” a credit for Harry Chesler’s managing editor George Nagle, who may have written one or more of these gags. Nagle’s name appears on several stories produced by the Chesler shop, and it’s thought that he wrote some of the material.

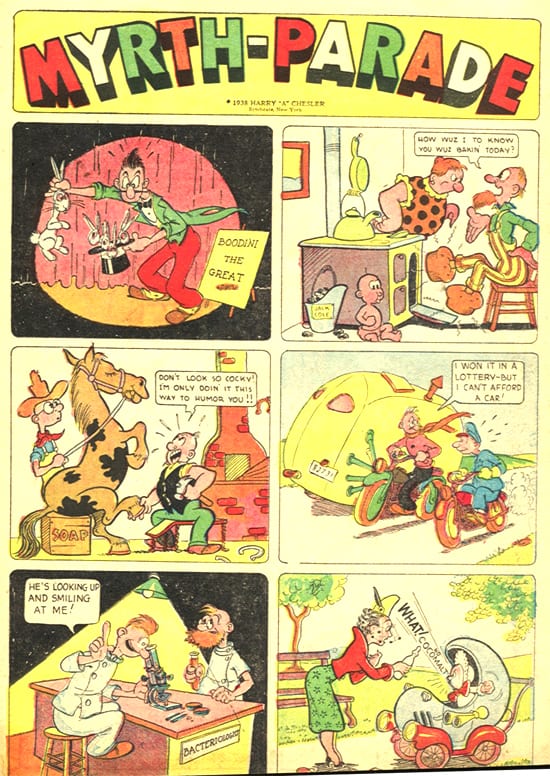

In some of the gag panel pages, Cole collaborated with other artists. In this page from The Cocomalt Big Book of Comics (circa August, 1938) Cole provides three gag cartoons while the others are drawn by some of the other cartoonists in the studio. Cole provides gags on this page for panels two, three, and six (with the last one featuring perhaps his first published sexy babe).

Cole's gag cartoons stand out from his fellow cartoonists. This is in part because they are festooned with additional sight gags. The baby carriage in panel six is comically tricked out and panel two has a funny sign on a bucket of coal -- Jack Cole's name!

Jack Cole - Screwball Pioneer

Jack Cole's 1938 work for Chesler is entirely devoted to humor. In addition to a regular weekly salary, Cole's employment meant he suddenly went from publishing a few gag panels a month to having pages to fill. This allowed him to stretch and grow. Instead of carefully cultivating certain types of gags with a narrow range of subject matter, Cole suddenly had a blank check to create more or less whatever he wanted -- as long as Chesler could sell it. In short order, Cole's humor comics became more nutty, more wacky, and more screwball.

The late 1930s were a peak of American screwball humor. The Sunday funnies featured crazy comics by Rube Goldberg (Lala Palooza), Milt Gross (That's My Pop), Bill Holman (Smokey Stover). and Gene Ahern (The Squirrel Cage). The Marx Brothers and The Three Stooges were killing them at the box office, and cartoon masters Bob Clampett and Tex Avery were creating their screwball masterpieces. The incomparably zany Hellzapoppin' was the hit Broadway revue of 1938 (followed by a surreal masterpiece of film comedy in 1941).

It could be argued that in 1938 Jack Cole was pioneering the development of screwball humor in the new medium of the comic book. His 1938-39 comics rigorously address themselves to the question of how to adapt funny background gags, exaggerated flips, sprints, and contortions of the human form, and visual puns into the format of the comic book.

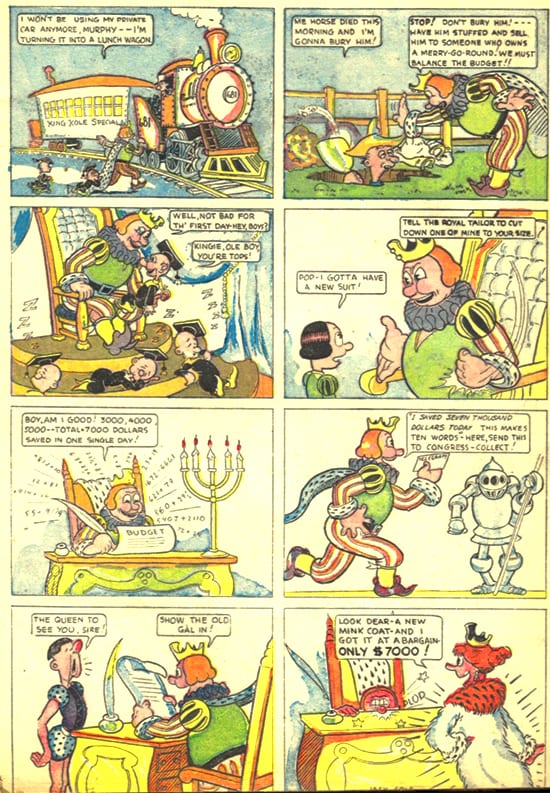

One of his early experiments was with a 2-page feature called King Kole's Kourt. It's tempting to say that Jack Cole created the continuing Chesler feature, King Kole's Kourt, because of the similarity in names, but this was actually a feature other Chesler artists established years before Jack Cole came aboard. In any case, whenever Cole drew the 2-page strip, he zealously invested it with his own brand of zaniness.

Interestingly, Jack Cole's father also played with the King Cole concept, using it in his State Farm insurance ads in the early 1940s. Another long-established, frequent Chesler feature was the jaw-dropping and racist Cheerio Minstrels. Although the core "humor" of the strip centered on the condescending portraits of the black minstrels, when Cole drew a two-page episode published in a Centaur comic book with a cover date of November 1938, his intense, breathtaking focus on screwball comedy made the racism irrelevant.

The surreal, Vaudeville-style call-and-response format that Cole re-shaped the Cheerio Minstrels into may have been inspired by Gene Ahern's Sunday newspaper screwball classic, The Nut Brothers, which ran as a topper strip above his more well-known comic, Our Boarding House from 1931 to 1965 (with Ahern leaving the strip in 1937 to then create The Squirrel Cage). It's likely that Cole read Ahern's comics growing up and while he was working in New York. Where Cole's characters ask "What does a maid say at the end of her prayers?" -- Ahern's Nut Brothers (Ches and Wal) ask, in beautiful surreal nonsense: "Why is a goat in your bed like lace curtains on fire?"

In his Cheerio Minstrels two-pager, Cole interlocks the two men in the same ways that Rube Goldberg engaged his twin characters, Mike and Ike (They Look Alike) -- a strip that was also invested with race issues (in its early years).

Observe, if you will, how, in the bottom of page one of the Cheerio Minstrels two-pager shown above, Cole pneumatically propels the characters around the panel. This exaggerated movement is another element Cole would develop, particularly in his Plastic Man stories. In fact, Cole recycled the fourth panel on page 2, with the arm amputation with a saw, in his first Woozy Winks story (Police Comics 13):

Stylistic Antecedents - Or, Plastic Man in Raw Pellet Form

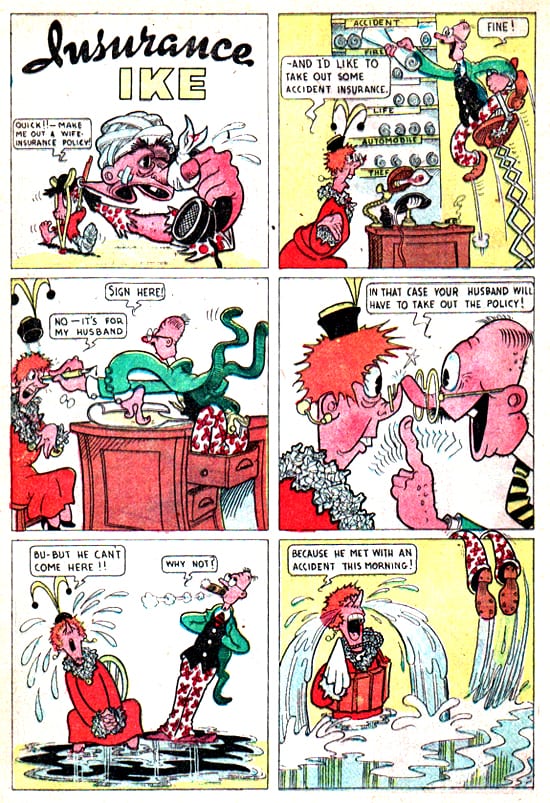

The early comics of Jack Cole often contain the first appearances of devices that would later become recurring motifs in his art. This can be seen in Cole's very early "Insurance Ike" page published in April 1938. Cole again puts the comic pedal to the metal, using every nutty idea he can devise, including an ingenious variation on the concluding flip-take (or plop, as it was sometimes called) in which a character dives out -- and behind -- the panel!

River of Tears

The image of a comically melodramatic "river of tears" is a staple of Cole’s comics, that seems to first appear in the above example 1938. The most memorable use of this device is in "Sadly-Sadly," Cole's celebrated 1949 Plastic Man story built around a character called Sadly-Sadly, a man with a face so sad that it causes people around to weep rivers and give him everything they have.

Plastic Man eventually defeats Sadly-Sadly by getting him to grin and then punching him in the face, to freeze the smile and rob him of his power. The Sadly-Sadly story from Plastic Man #20 overflows with images of comically hysterical weeping – an image that can be found throughout Cole’s work of the 1940s and 1950s, right up to his last masterpiece – the starkly bittersweet last Cole Playboy cartoon (July 1959) which depicts an older gentleman shedding impossibly large tears as he presumably spies a younger couple making love.

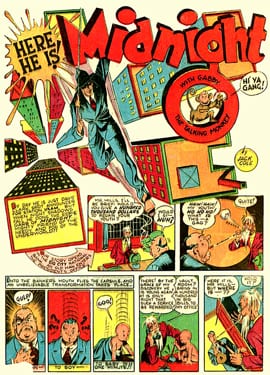

Extreme Camera Angles

Another hallmark of Jack Cole's comic book work is his use of extreme angles and perspectives. Cole enjoyed exploring all the spatial dimensions of his comic book worlds. In a single page, he can take the reader from eye-level to the gutter and then leap a hundred feet into the air atop a skyscraper.

Some of Cole's more dramatic page layouts employ extreme points of view, such as his Midnight splash page from Smash Comics #23 (June, 1941). In his Plastic Man stories, Cole developed this device even further. In one memorable scene Plastic Man stood at street level and stretched his upper body all the way to a fifth story window, through the window, into a drinking glass in someone's hand where he entered the straw in the tea from the bottom of a straw, and then popped his head and neck out of the top of the straw.

An early, if not the first, example of Cole's trademark extreme shifts in viewpoint appears in his four-page "Smart Alec" screwball story about making a movie. Perhaps the subject of making movies inspired Cole to burlesque the use of extreme "camera angles" in his strip. In any case, the device took -- and became an essential stylistic element in Cole's work that influenced dozens of other artists.

Rubbery Bodies

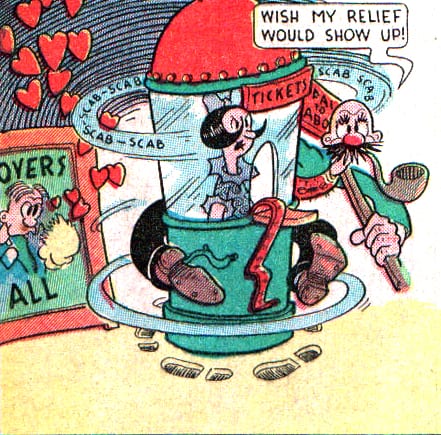

In his extremely early one-page gag strip about a professional union striker, "Joe Ticket (The Human Picket)," from Funny Picture Stories Volume 2, #7 (April, 1938), Cole not only crowds in background jokes and visual puns, he outrageously stretches the human form. This is something new in comics -- at least the way Cole does it. Curiously, Joe Ticket appears to be made of rubber as he curls his legs, arms, and fingers in comically impossible poses.

In panel three, Joe wraps his entire body like an eel around a ticket taker's booth. The phallic-shaped booth contains a pretty girl that Joe is pursuing. Check out that tongue-like spewing red cascade of tickets -- where in the booth is that coming from? And Joe is saying something about wanting to get relief soon. All of a sudden, we're looking at comedy with psycho-sexual undertones! It's Plastic Man, three-and-a-half years before his birth -- all that's missing is the red suit with yellow and black stripes and the cool shades.

Avast, Ye Schwab!

Note that the reference in panel two of the Joe Ticket page above to the actor "Garbo Schwab" is an in-joke that refers to Cole's new-found friend at the Chesler studio, Fred Schwab. Of all the early Chesler artists, Fred Schwab seems to be the closest to Cole's wavelength. His comics of this period, like Cole's, explore the screwball genre. Another sign that Cole and Schwab were pals is that some of Schwab's gag cartoons began to appear in 1939 issues of Boy's Life -- Cole's regular magazine market of the time. It's a safe bet that Jack Cole helped Fred Schwab sell to Boy's Life.

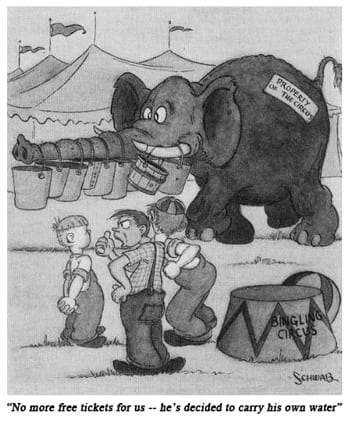

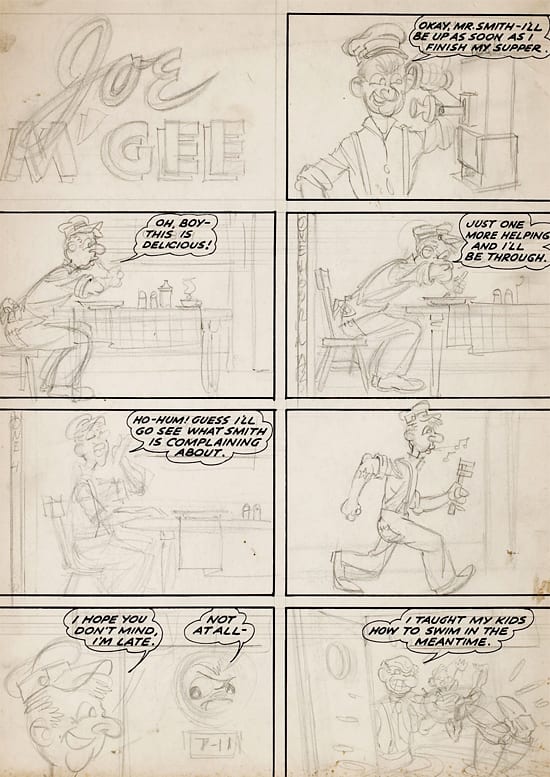

Before we leave the subject of Fred Schwab, I just have to share this cool piece of original art I found in digital form. This art, from the Chesler shop, was very likely created by Schwab while he sat next to Jack Cole. The fact that this is an unfinished page is important, because it gives us an idea of what Jack Cole's original art looked like in process.

I've Got a Fever and The Only Thing That'll Help is... More Screwball

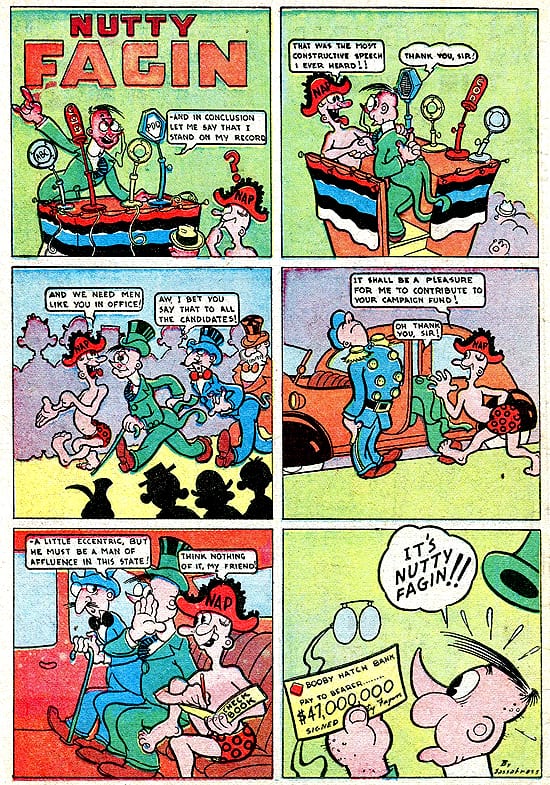

Jack Cole's Milt Gross-like Nutty Fagin (which playfully uses the pen name of "Sassafrass") one-pager, published in a book with a cover date of November 1938, also presents a character with a rubbery body. In panel three, Nutty Fagin, clad in polka-dotted boxers and Napoleon hat, walks with stretchy legs that curl around each other.

Looking at these early experiments of Cole's with ways to comically distort the human form, it seems almost inevitable that he would have his biggest hit when, in the summer of 1941, Cole devised a superhero with a rubber body. It's also easier to understand the virtuoso distortions Cole achieved in his Plastic Man stories when we realize that he had been working on the idea for years before he created the stretchy sleuth.

Making Soft Comedy From Hard Times

It’s interesting to see that some of Jack Cole’s earliest work in comic books appears to be somewhat autobiographical. In a 1938 one-pager (that also contains a "river of tears" image) featuring the sporadically appearing ‘Insurance Ike” Cole depicts the plight of an insurance salesman facing the fact that business is terrible. Cole draws Insurance Ike in a dark office shrouded with cobwebs. In the second panel, Ike sheds huge tears that form a pool at his feet and bemoans, “Oh boy! This insurance business sure is terrible!” Perhaps at the time, Cole could have said the same thing about the cartoon business.In the first panel, Ike berates his own reflection, railing “Ike you sap!” The reflection answers, “You ain’t so hot yourself!”

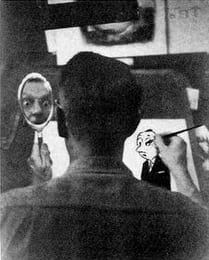

By this time, Cole may have begun to use the animator’s and cartoonist’s trick of keeping a mirror by the drawing board to help with depicting facial expressions. When he was photographed for a 1956 article, Cole incorporated his drawing board mirror into the composition, so we know that this was indeed a technique he used, perhaps as early as 1938. One can see Cole searching for an idea, picking up his hand mirror, looking it and suddenly thinking that it would be entertaining to draw a man having discussions with his own sarcastic reflection. In the third panel, Ike says to his reflection, “If things get any worse, I’ll have to let you go.” Could this existentialist conversation reflect something about Cole’s dark side? One can't help but wonder how many times Cole picked up a mirror and drew himself into his work.

The August 1938 Insurance Ike page from above is also interesting because it includes another visual device that would become one of Cole's favorite devices: the spotlight effect. A smart and talented designer, Cole used the triangular shape of spotlights to lead the eye, and the contrast in light and dark to add visual interest to his pages. The spotlight effect occurs repeatedly in Cole's comics. It was used very effectively, for example, in a composition for the fetching cover of Police Comics 27 featuring Plastic Man, Woozy Winks and The Spirit caught in the yellow bream of a streetlamp at twilight.

Similarly, an early King Kole's Kourt two-pager tells a story of financial worries. Like the Insurance Ike page above, the comic appeared in The Cocomalt Big Book of Comics, an advertising giveaway pitching an Ovaltine-like milk additive that the Chelser shop handled (and which Cole may have art directed, since the book contains a lot of his work and spot illustrations). In the strip, the King and his Kourt take drastic measures to cut expenses:

Jack Cole Stretches and Plays With Dynamite

As Jack Cole furiously wrote, penciled, inked, and lettered his way through 1938, he began to acquire a greater mastery and confidence in his work. His figures are less labored over and more confidently drawn. He moves away from the puppet-like figures towards more solid and streamlined figures, using them to lead the eye through the page. His inking and lettering improves, as does his writing. In fact, Cole's writing shows the greatest improvement, as he develops longer and more complex stories, such as Home In The Ozarks, his hillbilly hijinx series that ran up to five pages at a time.

Another notable improvement was Cole's introduction of creative design in his opening pages, effectively making them artistic statements that can stand on their own, as well as effective openings to his stories. (For more on Cole's development of the splash page, see my article, "Jack Cole and the Art of the Splash Page")

Longer stories with splashier art was very likely not just an artistic move on Cole's part, but a stretch to earn more money. If he stepped up his production, then he was worth more to his employer, Harry "A" Chesler. We know of 36 pages Cole did for Chesler in 1938. In 1939, we have identified 65 Cole pages, and then in 1940 a staggering 157.

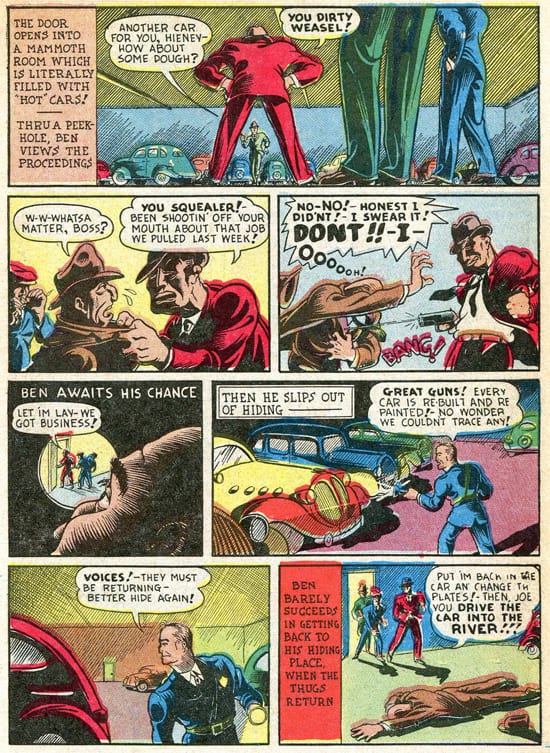

In addition to increasing his production, it seems likely that the gifted and ambitious young cartoonist decided to develop a second, more serious style of storytelling that would compliment his screwball work while increasing his potential for income. Cole's first published experiment in this new, non-humorous direction was a five-page crime story called Little Dynamite -- Cole's first great comic book story.

Little Dynamite is a potent, twisted powerhouse of shadows and vengeance. As we've seen, there were shadows curling around the edges of Cole's inspired -- if unskilled -- screwball comics. With Little Dynamite, Jack Cole unleashed his dark side. There is no gradual growth towards this noir style -- it emerges suddenly in Cole's work, like a killer lunging from a dark alley.

Published in Centaur's adventure-oriented title, Keen Detective Funnies #6 (Feb. 1939), the story represents a major change in direction for Cole introducing the theme of crime and punishment that would figure so prominently in his 1940s work. The story is also Jack Cole's very first creation of a heroic figure, the diminutive policeman who is nicknamed "Little Dynamite."

While Cole would go on to create literally hundreds of stories exploring the shadowy alleyways of morality and justice, he never did anything else that looks and feels like this textured art that seems to be burnished by light and darkness.

Cole dug down deep for this one. He has put so much effort into the artwork that it has a beautiful decorative woodcut quality. Not until his very last horror comics of the early 1950s would Cole drench his panels with so much darkness and shadow. Darkness seems to pour out of the grim, sadistic criminals, tainting the world around them.

In this story, Jack Cole has creatively invented his own unique approach to telling a dramatic story in comic book form. Little Dynamite explodes with fresh ideas. Cole jags the edges of his speech balloon in panel two on the first page of the story, indicating the words are said not only loudly, but emphatically. He mixes narration and dialogue to move the story forward. We also see here that Cole employs the same extreme points of view that he used in his earlier humorous piece, "Smart Alec," placing the “camera” on the floor, or high up in air at times, to heighten the drama of the story.

Most impressive though, is the story itself. The man who published more of Cole’s stories than anyone else, Everett “Busy” Arnold (Quality) told James Steranko that Cole was the rare comic book artist who could also write a good story.

In Little Dynamite, Cole becomes for the first time a hard-boiled pulp writer in the tradition of Mickey Spillane (who was writing for comics around this time), Jim Thompson and Charles Willeford -- investing the story with his own deep, dark material that gives it a compelling, but troubled energy. The story is a genre story, slotting perfectly into the crime drama format that flooded the pulpy pages of popular magazines and the roaring airwaves of radio. The title alone,”Little Dynamite,” is poetic. The “mite” part of the word “dynamite” resonates with “little.”

The story, about a diminutive policeman who uses his size as an advantage against hardened criminals, prefigures Cole’s most famous creation, Plastic Man. It is to career criminal Eel O’Brian’s everlasting credit that, upon discovering he has the ability to stretch his body at will, he imagines what a force it would be in fighting crime and redeeming himself. In this famous story, the origin story of Plastic Man, Cole again has a character using a deformity as an advantage.

Cole returned to deformity, or shape-shifting, over and over throughout his 16 year career in comics. His very last published comic book story, “The Monster They Couldn’t Kill” (Web of Evil #11, Feb. 1954) deals with deforming the human body. In his Plastic Man stories, evil men often become powerful through deformity. And, of course, Plastic Man himself is all about changing shape and identity.

Little Dynamite also speaks to the idealism and nobility of purpose that Jack Cole embraced in his early life. Far from being cardboard characters, the policemen in this story are highly motivated by a sense of good, which shows in how they treat each other with decency and support, and in the brave act of heroism the diminutive policeman demonstrates when he goes against the car-stealing gang.

Most significantly, with Little Dynamite, Jack Cole managed to successfully create a non-humorous dramatic story that contains the same level of manic energy as his screwball comics. In just 12 months, Jack Cole had established a new career for himself working not in magazine gag cartoons, as he had planned -- but instead developing first wildly zany humor material for comics books, and then branching out into serious crime stories. His next year at Chesler would show more meteoric artistic development as he stretched toward Plastic Man and beyond.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

FRAMED!Works

1. Just to show you Framed! has vim and variety for you, next month's column will present "something completely different." We'll pick up the Jack Cole "Lost Comics" series the following month after that.

2. Shout-Out to the Digital Comic Museum

With the emergence of digital scans of rare old comics – many of which few can afford to acquire – we now have the ability to systematically study comics history like never before. The loose affiliation of collectors and scanners who have increased their karma goodness by unselfishly making scans of thousands of old comics available at the Digital Comic Museum are, in my opinion, among the great benefactors of this little understood art form. By making it possible for us to actually read the comics for the first time, instead of relying on verbal descriptions or altered reprints, these people have made it possible for us to finally approach comics history with true authority and authenticity. I would never have been able to develop this look at Jack Cole’s first comic book work without this access. Thank you, and keep it coming, guys!

3. The Harry Chesler Collection of Cartoon Art and Graphic Satire

Pioneering comic book publisher Harry Chesler became a comics historian in his later years, amassing thousands of rare books and studies of the form. In 1974, apparently with support from James Steranko (who wrote an appreciation for the original collection’s catalog, now a rarity sold for $25-$100 when you can find it) and Joe Kubert (who got his start in comics from Chesler), he donated his entire collection of books, comics, papers, and original art to the Fairleigh Dickinson University. At some point after that, the original art (which included Winsor McCay originals) was sent to the Library of Congress, and about 3,000 books on comics went to Drew University in New York. You can view the collection’s holdings – a useful bibliography on comics writing in itself, here: https://uknow.drew.edu/confluence/display/Library/Chesler+Collection

4. New Buster Keaton discovery here (http://silentlocations.wordpress.com/2013/07/20/found-a-new-version-of-keatons-the-blacksmith-and-the-tales-it-tells/)

5. I'd like to send out a celebratory CONGRATULATIONS!!! to my friends Frank M. Young and David Lasky for winning a 2013 Eisner Award for their graphic novel, The Carter Family: Don't Forget This Song. The book won an award for "Best Reality-Based Work." The winners of the 2013 Eisner Awards were announced July 19, 2013. Frank was also up for an Eisner for Best Writer. That award went to Brian K. Vaughn. Be sure to check out Frank's blogs:

Stanley Stories (An exploration of the work of John Stanley)

Supervised By Fred Avery: Tex Avery's Warner Brothers Cartoons

Comic Book Attic (co-authored with me)

And check out David Lasky's blog:

http://dlasky.livejournal.com/

And you can read many fascinating behind the scenes postings about the making of this Eisner Award winner at Carter Family Comics: Don't Forget This Blog!

I'm very happy for Frank and David. I was around when they started the project. In fact, they worked on the book for several months in my office, here in Seattle. It was fascinating to see them sifting through piles of books, papers, recordings and other source material (the book is meticulously researched). I was honored to see the first pages penciled and to read early versions of the book. What was supposed to be a project that would a year of work for the two men wound up taking four years from each. Many sacrifices and hardships were endured to get through the process of creating the book. Congrats, guys!

6. Recently Read and Recommended

6. Recently Read and Recommended

A Curious Man by Neal Thompson. This well-written biography of cartoonist Robert L. Ripley satisfyingly fills a gap in comics history. In his lifetime, Ripley was the most famous and highest paid cartoonist in the world. I enjoyed reading Thompson’s book on this strange man. The scholar in me wishes there were more information, and I have to restrain myself from pointing the few, very small errors and inaccuracies that only a comics geek like me would care about (such as the fact that in his early years as a New York cartoonist Rube Goldberg created many more strips than just his "Foolish Questions" panel). The book is obviously written for a broad audience, and in this respect, it succeeds beautifully. I suspect that curious Odditorium visitors (by the way, it was interesting to learn that the Ripley’s museums are in no way connected the family any more) will be as fascinated by this book as they are with exhibits of shrunken heads and the Brooklyn phone directory written on a single grain of rice. I enjoyed learning about Ripley’s origins, his weird island home, and his inspiration to design a stunning memorial for the people who died in the December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. Did you know that Charles Lindbergh was the 67th man to make a non-stop flight across the Atlantic? Believe it not, the crocodile is an insect!

7. Additional Jack Cole pages from the 1938 Cocomalt Big Book of Comics are shown in my latest post at my Cole's Comics blog

If you liked this piece, please leave a comment -- it helps make it possible for me to do more like this.

Till next month,

Paul Tumey