When he was in high school, Cole would quietly sneak into his family’s kitchen in the middle of the night where he would assemble and wrap a sandwich for his school lunch the next day. Back in his room, he would hide the sandwich inside a hollowed out book.

His boyhood room contained cabinets Cole – a sort of small town Buster Keaton -- built, complete with hidden compartments. One of these compartments held electronic gear Cole had assembled that allowed him to eavesdrop without detection on his family’s telephone calls. Much like his 1940-41 comic book character, Dickie Dean, a boy inventor (who lived in New Castle, Pennsylvania, Cole's hometown), the young Jack Cole was endlessly resourceful.

Smuggling a sandwich to school allowed Cole to secretly save his lunch money to invest in his passion: cartooning. Cole eventually saved up enough quarters and dimes to buy correspondence courses from the Landon School of Cartooning -- courses that his father, a small business owner, had refused to subsidize.

A career born from such stubborn resourcefulness and playful secrecy is bound to hold some surprises. Over half a century after Jack Cole’s life abruptly ended, we are still discovering his secrets.

The general arc of the life and work of Jack Cole, who was born December 14, 1914 and died August 13, 1958, is fairly well documented.

Cole is famous for his numerous Plastic Man stories -- a bulging, jam-packed inventory of screwball humor, breakneck storytelling, visual innovation, underground eroticism, and dark obsessions that stretches from the birth of the American superhero comic through World War Two and into the first days of Cold War dread in America.

It’s also well-known that Cole miraculously re-invented himself as a gag cartoonist for sex-drenched men’s magazines when the comics industry collapsed in the early 1950s. With apparent meteoric speed characteristic of his comic book stories, Cole swiftly skyrocketed to the top of his new profession as Playboy’s premier cartoonist, creating jaw-dropping, libido-stoking cartoons that were “loose and juicy,” as fellow Playboy cartoonist Al Stine once described them.

As if that ascent weren’t enough, Jack Cole reshaped himself yet again, transforming overnight and out of the blue into a syndicated newspaper comic strip artist -- the coveted achievement for a cartoonist of Jack Cole’s generation. Mere months after reaching this pinnacle, Cole tragically took his own life on August 13, 1958 at age 44.

These are the fairly well-known, if sketchy details of the life and career of Jack Cole. Over the years, several comics historians and artists have produced valuable works on Cole. These include, among others, James Steranko, Ron Goulart, Art Spiegelman, and R. C. Harvey. In recent years, the availability of golden age comic book scans, digital newspaper archives, and old photos and records via the Internet has made it worthwhile to do some further “Cole mining.”

Some of the less well-known revelations that emerge include the fact that, in addition to his comic book career, Jack Cole cultivated a shadow career as a magazine cartoonist, selling numerous gag cartoons to top-paying, nationally distributed magazines, such as Boy’s Life, Judge, Collier’s, and The Saturday Evening Post. Even more obscurely gleaned is the fact that Cole also sold stacks of gag cartoons to the low-paying markets, as well. Places like Stamp Wholesaler and Army Laughs. His re-invention in the early 1950s from comic book master to magazine cartoonist was more about picking up where he left off a few years previous than starting from scratch.

It’s also virtually unknown that, while he worked in the mid-1950s as Playboy’s premiere cartoonist, with work appearing in every month’s issue, Cole wrote and drew for nearly two-and-a-half years a highly obscure monthly newspaper comic strip that served as a training ground for his 1958 syndicated strip, Betsy and Me.

A study of Cole’s lesser-known –and mostly forgotten – comics and cartoons sheds light on his greatest work, his Plastic Man stories and Playboy cartoons. It also reshapes in fun, manic Plastic Man fashion our current narrow understanding of this secretive, influential 20th century pop artist who was never interviewed, never profiled in his lifetime, and rarely even photographed.

Spin Control: (1931-32)

Jack Cole was born and raised in a small Pennsylvania town called New Castle. He was the second oldest in a family of five children. In 1931, Jack was a thin, gawky, good-natured sophomore in high school. The local paper, The New Castle News, carried daily and Sunday comics sections, and ran Rube Goldberg’s screwball comic on the sports page. Young Jack Ralph was deep into scouting, applying himself to earning merit badges with the same driven single-mindedness of purpose that he would also demonstrate in learning the craft of cartooning.

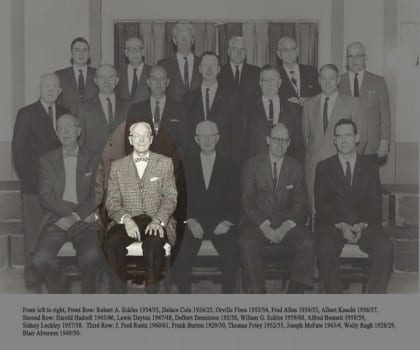

The head of the Cole family in 1931 was DeLace Cole (1881-1968), a 50-year old dry goods merchant born and raised in Pennsylvania. A president of the New Castle Rotary #89 in 1924 and 1925, DeLace enjoyed life as a semi-public figure in New Castle, speaking and performing for the many local clubs. He sometimes appeared as “King Cole,” a play on the family surname’s intersection with the old nursery rhyme that his son Jack would also capitalize on when he created his “King Kole’s Kourt” humor comic series in 1938. In the 1950s, DeLace become a State Farm insurance man and advertised himself as "Old King Cole.”

DeLace appears to have taken active role in raising his children, appearing as a guest when Jack and his younger brother Bob were inducted into the Elks Boy Scout Troop Number 5. On the evening of January 23, 1931, Jack was present when his father spoke to local youth at the Y.M.C.A. as near-freezing rain fell outside. The next day, the local paper reported that DeLace’s speech “included words of wisdom that young men and women present could not overlook.”

Here's a snapshot of the Cole family in 1930. Cole’s mother, Corabelle (48), was originally from New York and sometimes worked as an elementary school teacher. The rest of the Cole family consisted of Claire (18) whose 1931 job consisted of clerking in a local department store, Jack Ralph (16), Betty (13), Robert (11) and Dick (9). A sixth child, DeLace Jr., died at age 11 in 1919, when he was hit by a truck. Losing his older brother when he was five to an automobile accident may have left an indelible mark on Jack Cole, who would go on to draw numerous images of people outracing speeding automobiles in dozens of comic book stories.

The clan lived in a two-story home owned by DeLace at 411 Euclid Avenue – where they stayed until 1938, when DeLace relocated the family to a nearby town for a three experiment in owning his own dry goods store. The Coles returned to New Castle in 1941, where they stayed.

Jack Cole's boyhood home was blocks away from the stately wrought iron gates, crumbling tombstones and Gothic-era crypts of the city cemetery, where the future creator of grisly horror comics may have ridden his bike on moonlit nights.

Jack Cole may have been first inspired to take cartooning seriously when, according to comics historian Jerry Bails, he landed a cartoon in a 1931 issue of the popular magazine Open Road For Boys.

The monthly magazine ran a “Cartoon Contest” page in every issue that published young cartoonists’ solutions to a problem cartoon. One such problem, in the February 1939 issue presented a cartoon and verse detailing a mountain hiker’s encounter with a hungry bear. The magazine’s cartoon page offered cash awards and the thrill of publication. The “Cartoon Contest” became the first publisher of several career cartoonists, including Mort Walker, Bill Yates, George Crenshaw, and Disney animator Bill Peet. While the date of publication and Cole’s cartoon remain as yet undiscovered, it seems a safe bet that this was a significant event in the 15-year old’s life.

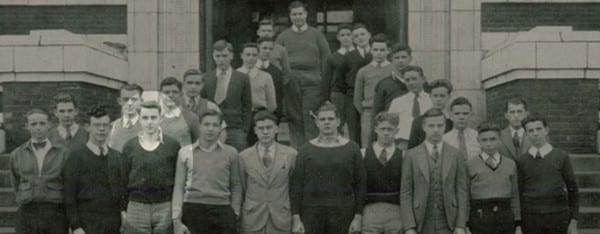

From 1929 to 1933, Jack Cole attended New Castle High School, a large K-12 public school housed in a multi-floored brick building with broad stone steps leading up to the entrance.

The administrators of New Castle High placed a strong emphasis on extra-curricular activities. Nearly every student in Jack Cole’s class logged participation in at least a couple of the school’s many clubs, teams, and cultural events.

While one might expect that the budding young cartoonist would turn up in the school literary society, or the yearbook staff – his extracurricular activities are surprisingly physical and social. His graduating yearbook from June, 1933 lists the following:

Jack Cole

Track (11);

President HI-Y (11);

Student Representative (10-11).

In 1932, in his Junior year, Cole served on the Student Council and as President of the HI-Y Club, a group that went swimming weekly at the local Y.M.C.A. and put on a school play. In a 1932 photo of the HI-Y lads, Cole stands among his peers, a tall, good-looking boy elected as the leader of the group. Perhaps, at the time of this photo, Cole was already planning his summer adventure – a journey that would require outstanding physical conditioning. Originally, this trip was planned with some of Cole’s friends, perhaps fellow members of the HI-Y Club, but when none of them were allowed to go, Cole decided to go on his own.

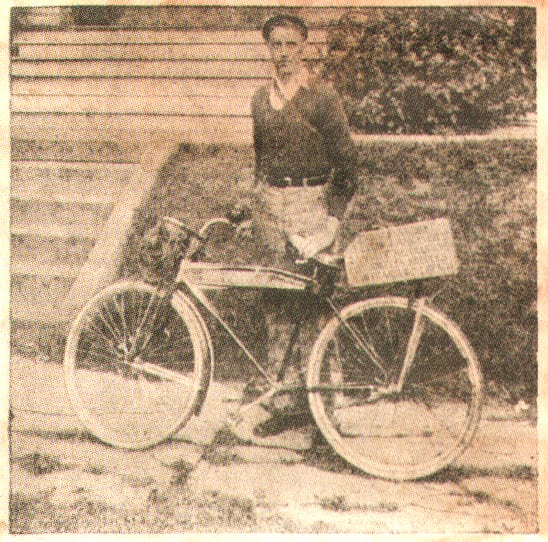

On July 13, 1932 at 5 o’clock in the morning, a 17-year old Jack Cole finished loading his bicycle up with – among other things -- blankets, a pup tent, a raincoat, clothing, tools, a medicine kit, cooking utensils, food, a flashlight, towels, soap, a harmonica, a Bible (Cole was raised as a Methodist), and – of course – paper and pencils. He straddled the comically overloaded two-wheeler and set out on what would turn out to be a 7,000 mile jaunt across the United States.

Later that day, an item appeared on the front page of the New Castle News, the town’s newspaper with the headline “Lone Youth Off Today For ‘Bike’ Trip to Olympics.” The article reads, in part: “Alone but confident, young Cole, who plans to cover from 50 to 75 miles each day, left with the hopes of reaching the western coast in time to see the world’s athletic classic.”

An exuberantly wacky teen adventure and a seemingly impenetrable mystery surround what may be Jack Cole’s first professional sale. “A Boy and His Bike, “a jaunty, prosaic piece that spins a compelling story about Cole’s epic 1932 summer trip, was likely Cole’s first sale – but, some eighty years later, the actual details of when and where this piece was originally published remain forgotten.

In his 1972 book, The Steranko History of Comics Volume 2, James Steranko includes a chapter on Jack Cole and Plastic Man that is based in large part on information and documents supplied by Cole’s younger brother, Dick Cole. The centerpiece of the chapter is a complete transcription of a breathless 2,000 word article by Jack Cole (which you can read here) that tells of his adventures riding a bicycle from his hometown of New Castle, Pennsylvania to Los Angeles, California – and back. It’s an extraordinary account, and anyone familiar with the condensed, jet-speed storytelling style of Cole’s Plastic Man stories will recognize the essence of Jack Ralph Cole in the piece.

In short, pithy paragraphs, Cole details both the rigors and fun of his trip. At last, the boy from the uneventful small town had something to tell stories about, and he clearly relished the opportunity he had created for himself. His pacing and framing anticipates the way he would break his comic book stories down into connected panels always framing the story in screwball angles:

“One week on the road took me to St. Louis, Missouri. Two days later, while stopping for the night near a swamp, I was awakened from sleep to find my face a mass of stinging, swelling welts. Mosquitoes – hundreds of them – were attacking me savagely from every angle, and I was forced to spend the remainder of the night with a wet towel over my face, leaving only my nose protruding.”

It’s not hard to imagine a comic book sequence of this scene, given the way Cole writes it.

Steranko presents Cole’s account of his bike trip with no mention that it was ever published before its appearance in his book. In their 2001 book, Jack Cole and Plastic Man; Forms Stretched to Their Limits, Art Spiegelman and Chip Kidd reproduce Cole’s bike trip account in its original form, as a tear sheet. The article, as it turns out, included cartoon illustrations by Cole. Spiegelman and Kidd credit it as his first sale, to Boy’s Life in 1935. The mystery around this piece becomes evident when a careful page-by-page search of Boy’s Life in 1935... and then in 1934,1933, and 1932... reveals no such article. A query to Art Spiegelman about this resulted in his kindly sharing the information that he received a Xerox of the article's front page from Cole's younger brother, Dick Cole, who indicated it was published in Boy's Life. Could Dick have mis-remembered?

To make matters even murkier, Jack Cole himself noted in a 1956 Freelancer article that his first sale was to Boy’s Life in 1935 (his first Boy’s Life cartoon actually appeared in 1936), apparently either forgetting about or deliberately omitting his bike trip article (which was likely published before 1935, since he completed the trip in October, 1932). Cole doesn't indicate if that first sale was a gag panel cartoon, or his bike trip article.

It's possible that "A Boy and His Bike" ran in a regional or local scouting publication. Or, perhaps the piece was published in a local newspaper. The layout and typography resemble 1930s rotogravure newspaper Sunday supplement sections. Or, maybe it ran in a national magazine, such as Open Road For Boys (which is similar in content and approach to Boy's Life).

In any case, what may be Jack Cole's the first professional publication, and most certainly is one of the great artifacts of comic book lore, remains undocumented – we don’t know when or where this piece appeared.

As it happens, Cole did indeed reach Los Angeles in time for the summer Olympic Games that year, but lacked enough money to buy admittance. After hanging around in a cheap hotel for a week and then visiting some friends, Cole biked and hitch-hiked his way home, arriving the evening of October 11, 1932.

About a year later, probably with the help of his socially active father, the roads scholar gave a prepared talk about his adventure around town, appearing at the local Rotary Club (April 8, 1933), The Kiwanis Club (July 12, 1933) and the Lion’s Club (July 15, 1933). According to a newspaper account, Cole’s “humorous recital” included an exhibition of his cartoons about the trip. Perhaps these resembled the same cartoons that were published in his article.

“Jack Cole, Cartoonist” (1933-35)

In June of 1933, Cole graduated from New Castle High School. His yearbook photo shows a handsome young man with a world-conquering look in his eyes. Each graduating senior that year received a nickname. Jack Cole, the young man who rode a bike 7,000 miles across America and back, received the moniker of “Marco Polo.”

He was also listed at the top of the student’s Who’s Who, and deemed the “cleverest” student in his class. Most tellingly, the yearbook staff page records the following: “Jack Cole, cartoonist.”

The New Castle High yearbook published in June, 1933 (Jack Cole’s graduating class) contains a single, full-page cartoon by Cole. In the cartoon, which portrays a New Castle High chemistry student’s nightmare, Cole displays the very same go-for-broke, jam-packed screwball sensibility that characterizes his later comic book stories. In the cartoon, Cole ambitiously pastes photographs of the school teachers into his cartoon and skillfully integrates them with his pen-and-ink drawings.

The "Baldpate" gag refers to a school play that Jack helped write and acted in, earlier in the year. It seems likely that this cartoon was representative of the type of material Cole created and ran in his self-published school newspaper, The Scoop, which Steranko writes “parodied the faculty of New Castle High with cartoons and needled his classmates with all kinds of gossip.” Cole secretly printed The Scoop on his father’s mimeograph machine – yet another place where Cole’s strides toward individuation were cloaked in secrecy. Cole’s effort at self-publication collapsed when a made-up story led to a fellow student’s expulsion (perhaps this is why Cole chose to spend his summer of 1932 in absentia, travelling across country). Given this incident, it seems especially forgiving and appreciative that Cole was allowed a page of cartoons in the school’s official yearbook. Perhaps it was intended to be an encouragement.

Rube Goldberg, a prime influence on Jack Cole, recalled that, when his cartoons were first published in his high school newspaper, “… all hope was gone for being like other people. Every time the school paper came from the press and I saw my drawings reproduced I felt sorry that everybody couldn’t be as talented as I was." (It Happened to a Rube by Rube Goldberg, Saturday Evening Post - November 10, 1928). It seems a safe bet that Cole must have also had a similar thrill when his full-page cartoon ran in the school yearbook.

After graduation, Jack Cole took a job with the local American Can Company, then the nation’s largest manufacturer of tin cans, with factories located across the eastern United States. On March 29, Cole performed with several others in a live mock radio program for a local school. According to a newspaper account, “Jack Cole acted the role of announcer well.” Deep inside the noisy American Can factory, the restless Cole planned another getaway – an idyllic-sounding canoe trip down the Mississippi River with his brother Bob. Cole’s younger brother, Dick, recalled that Jack even built a canoe in their backyard in preparation for the adventure.

And then Jack Cole met a girl.

“When Cupid hits, he REALLY slugs --- so Dorothy and I eloped at 19,” Cole recalled in 1956. On July 7, 1934, Jack Cole abandoned his travels plans and his canoe, and instead took a short trip with Dorothy (“Dot’) Mahoney – who lived just three and half blocks from Jack at the time -- to New Brighton, about a half hour’s drive south of New Castle, where they were married – you guess it, in secret. Cole enjoyed telling the story how he convinced a tramp in the street to serve as his best man).

Even though he was apparently smitten, Cole – a man of secrets -- came back from his elopement to live with his parents, keeping the news of his marriage from them, at first. Looking at how he conducted his life and career, it becomes evident that Jack Cole was compelled – often in vain -- to protect the things that mattered most to him by controlling who knew what. In short order, the news of the couple’s secret marriage came out, and was quickly announced in the papers eleven days later with a fair measure of spin control, announcing that Jack would be living with Dorothy at her parent’s home, a five minute walk from the Cole family home.

But Jack Cole would not be stuffed into a can, an in-laws’ home, or a non-creative life in a small town.

It’s a Boy’s Life, But It’s A Man’s World (1935-37)

In 1936, Jack Cole was married and out of school. Working in a can factory, and living in the home of his wife’s parents, the exuberant Cole needed an escape route out of New Castle and a lifetime of mediocrity.

It was time to prove himself as a cartoonist. He began to create and submit cartoons to nationally distributed magazines. Those months of factory drudgery by day, in-laws and rejection slips by night must have been long and trying for the sensitive artist. One can only imagine the excitement when Cole finally sold some gag cartoons to editor Irving Crump at Boy’s Life. A scout leader himself, Cole must have felt a great sense of encouragement, knowing his fellow jamboree jostlers from all over the country would be reading his cartoons. The October, 1936 issue of Boy’s Life featured two Cole cartoons, including one with color tints placed on the inside back cover.

Cole himself later characterized his early style as “puppet figures,” and this is certainly evident in these cartoons, where the pear-shaped, long-armed bodies of the characters have exaggerated forms and lack a sense of mass. As he would in the first few years of his gag cartoon and comic book work, Cole used a heavy outline around his figures. Heavily influenced by the Landon Cartooning School style, Cole’s first comic characters seem to be hired from 1920s and 1930s Cartoonland’s central casting office.

Boy’s Life editor Crump announced in the October 1936 issue that the magazine would be carrying more comics and cartoons in future issues, to meet reader demand. This was good news for Cole, who would publish 22 cartoons in the publication over the next four years, only ceasing his submissions when he was hired on as a featured writer-artist at Quality Comics.

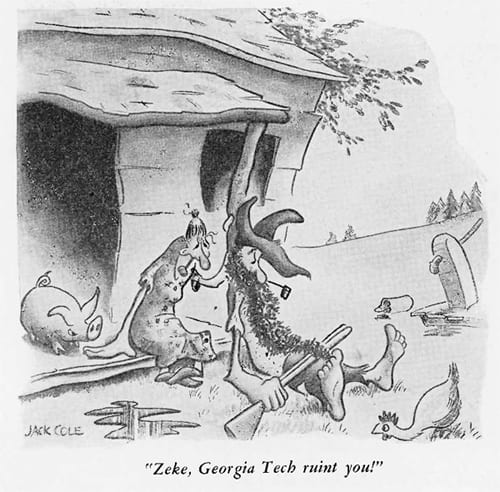

Cole followed up his success with Boy’s Life by placing a cartoon in the December, 1936 issue of the nation’s leading humor magazine, Judge. The subject of the cartoon, hillbilly life, would later figure in his comic book work with features such as Home In The Ozarks, The Hi-Grass Twins, numerous Slap-Happy Pappy one-pagers, and several Plastic Man stories.

Cole did not place another cartoon in Boy’s Life for 11 months. During this period, he escaped from the confines of New Castle. In an early version of a Kickstarter campaign, Jack Cole raised money from family, friends, and hometown merchants to subsidize a move to New York City with his wife Dorothy. Cole’s ambition at this time was, as author and comics historian Ron Goulart wrote in his article “Jack Cole, Gag Cartoonist” (Comic Art 2, February 2003), “to become a magazine cartoonist.”

Go East, Young Man (1937)

By the time his next known published work appeared (a cartoon in the September 1937 issue of Boy’s Life), 11 months later, the Coles were living in New York City, in a modest apartment on West 14th Street, located in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan. The trek to the publishing capital of the United States was one that cartoonists had been making since the turn of the century. From 1905 to 1912, TAD, Rube Goldberg, and Robert L. Ripley all crossed over by train from San Francisco. Cole’s pilgrimage fits the classic archetype.

The second half of 1937 was a grim time for the young newlyweds. As James Steranko wrote in The Steranko History of Comics, Volume 2, “(Cole) produced stacks of one-panel gag cartoons, but sold few. Even those that sold often took forever to pay off.” Steranko tells a story, possibly related by Cole’s brother Dick, where a desperate, starving Cole used his very last nickel as subway fare to travel to the Brooklyn office of a publisher who owed him money. Cole “discovered the publisher (was) almost as broke as he was. The man’s wife gave Jack a piece of cake to take home and share with his own wife.”

In the fall of 1937, Cole’s sales to Irving Crump at Boy’s Life must have been a huge relief, as welcome as his first sales about a year earlier. The September 1937 issue carried three Cole cartoons, all more visually powerful and accomplished than his first sales to the magazine.

From this point on, until late 1940, Boy’s Life would be a regular market for Cole, whose cartoons appeared most months. His cartoon in the November 1937 issue revealed a flair for surrealism in his humor.

Cole’s signature on these early professional sales is a labored, ornate visual gag in itself, custom-designed for Boy’s Life, showing an assortment of bent sticks spearing marshmallows ready to roast on the “Cole” of the signature.

This Guy’s A Riot! (early 1938)

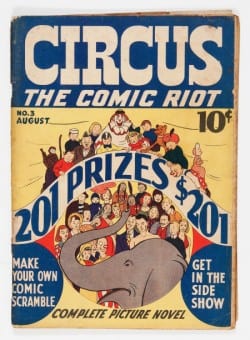

On January 25, 1938 the newspaper back in Cole’s hometown reported on the intrepid artist’s “rapid progress” as a cartoonist in New York. The big announcement was that “… it is likely that within a short time he (Cole) will sign a long term contract with the Globe Syndicate.” It seemed that, in less than a year after moving to New York, Cole had a shot at a syndicated comic – the brass ring for any aspiring cartoonist of the era. Cole had every reason to be excited. The owner of the Globe Syndicate was Monte Bourjaily, a powerful, connected and visionary publisher. He was the former head of United Features Syndicate, had briefly owned Judge magazine (which he sold in 1937), and in 1936, he bought the New York Times Mid-Week Pictorial magazine. With his 1937 Circus The Comic Riot venture, Bourjally had the idea to leverage the popularity of comic books to establish new line of syndicated properties. Globe published three issues of Circus The Comic Riot, a comic book that included early work by Basil Wolverton, Bob Kane (creator of Batman), and Will Eisner.

On January 25, 1938 the newspaper back in Cole’s hometown reported on the intrepid artist’s “rapid progress” as a cartoonist in New York. The big announcement was that “… it is likely that within a short time he (Cole) will sign a long term contract with the Globe Syndicate.” It seemed that, in less than a year after moving to New York, Cole had a shot at a syndicated comic – the brass ring for any aspiring cartoonist of the era. Cole had every reason to be excited. The owner of the Globe Syndicate was Monte Bourjaily, a powerful, connected and visionary publisher. He was the former head of United Features Syndicate, had briefly owned Judge magazine (which he sold in 1937), and in 1936, he bought the New York Times Mid-Week Pictorial magazine. With his 1937 Circus The Comic Riot venture, Bourjally had the idea to leverage the popularity of comic books to establish new line of syndicated properties. Globe published three issues of Circus The Comic Riot, a comic book that included early work by Basil Wolverton, Bob Kane (creator of Batman), and Will Eisner.

Cole created his most accomplished piece of screwball cartooning yet, a series called “PeeWee Throttle in Fuzzyland” (the New Castle News lists the name of the feature as “PeeWee Twittle,” perhaps an earlier version of the name).

With the zany energy of a three-ring circus, Cole's new feature rolled out the wacky adventures of a smiling young lad named PeeWee and his wacky inventor father, Si Throttle. The dense pages of the comic stitched together the panels of rectangular four-panel long comic strip installments – all ready for newspaper consumption.

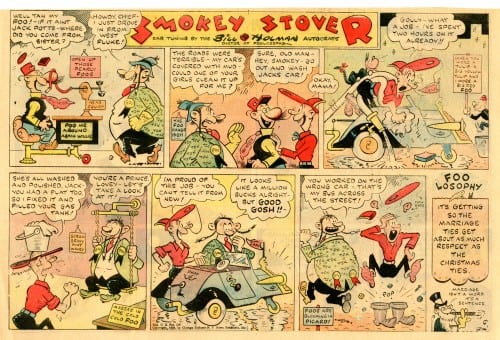

Cole’s feature is something of breakthrough in both the polish he brings to the cartooning and the ramped-up screwball intensity. Never has Cole’s work seemed more similar in appearance and tone to Bill Holman’s screwball comic strip, Smokey Stover, which began three years earlier, in 1935. A harbinger of the Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder Mad stories, Cole stuffs his panels with background gags, visual puns, and surreal, stream-of-consciousness imagery.

Cole obviously worked hard on this feature, with the promise of a syndicated strip in sight. Unfortunately, Bourjaily’s venture collapsed like a big top after the last performance, and it be another twenty years before Jack Cole finally achieved his own syndicated comic strip.

A Glimpse of the Big Time: Collier’s (1938)

In just a few short months, Cole’s Boy’s Life gag panels became more self-assured, and his visuals became more interesting as he latched on to the idea of screwball cartooning – a particular form of comics that traced back to cartoonists such as Dr. Seuss, Milt Gross and Rube Goldberg, in which multiple gags are simultaneously presented. The crazy energy of screwball comics seemed to torque the mental and physical state of the characters themselves. The result was a rich, distinctive high-octane style of cartooning that only certain masters could carry off successfully. Cole seemed drawn to this form of compressed goofiness from the start – perhaps the constraints of small towns, can factories, and in-laws’ back bedrooms made his own creative energy feel packed down.

In these cartoons, we see Cole’s early efforts to master wash and watercolor for magazine reproduction. The results in these first published works are murky. 14 years later, Cole’s Humorama and Playboy cartoons would demonstrate a stunning mastery of wash and watercolor technique that, as author and comics historian (and Comics Journal columnist) R. C. Harvey wrote in his article “The Mystery and Mystique of Jack Cole” (Comics Journal, October 1999), “defined what a Playboy cartoon should look like.”

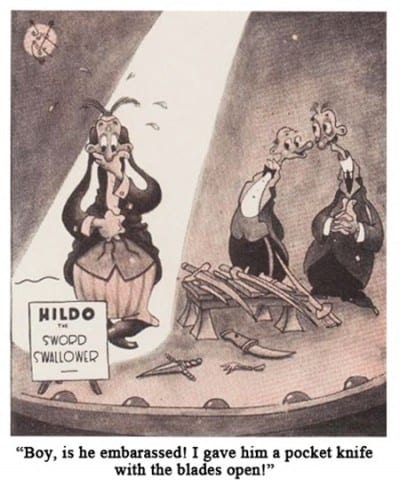

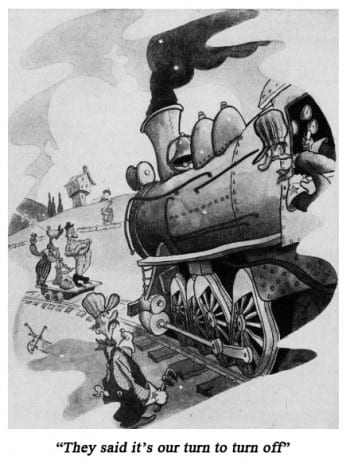

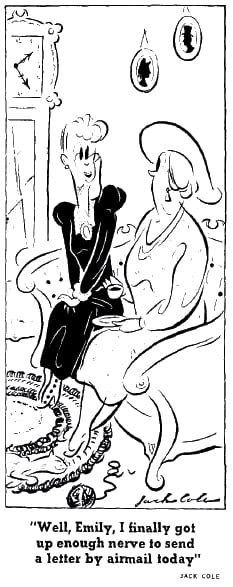

Throughout most of 1937 and 1938, Cole was barely surviving in a small apartment in Manhattan with his wife, desperately struggling to develop other markets for his gag cartoons. As Cole himself put it, "Here a buck -- there a buck --- I tried style after style until I finally sold one cartoon to Gurney Williams, then at Collier's magazine." His first cartoon appeared in the August 27 issue:

Gurney Williams was the cartoon editor for Collier's, American Magazine and Woman's Home Companion, markets that paid $40 to $150 for each cartoon. From a mind-numbing pile of some 2000 submissions each week, Williams made a weekly selection of 30 to 50 cartoons, lamenting:

"The other day I found myself staring at the millionth cartoon submitted to me since I became humor editor here. I wish it could have been fresh and original. Instead, it showed several ostriches with their heads buried in the sand. Two others stood nearby. Said one to the other: 'Where is everybody?' " (Time Magazine, August 12, 1946)

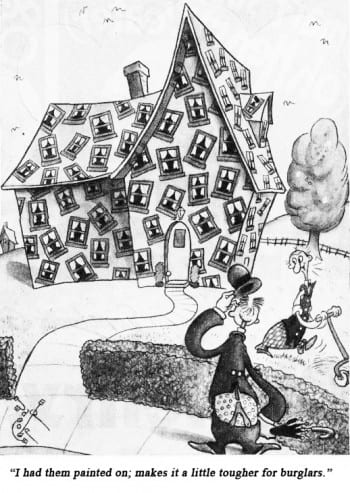

Cole’s offbeat humor probably caught William’s eye – in any case, Cole had successfully developed a style that worked for Collier’s. His first sale to the weekly magazine that was read by millions is drawn in a completely different style than his Plastic Man and Playboy work.

It's a loose, fragmented, agitated brush style. Cartoon editor Gurney Williams seemed to prefer cartoons with clean, thin brushwork and Cole appears to be working hard to master the technique. A few years later, Alex Toth visited the office of Quality comics and spent a little time hanging out with Cole. Toth recalled that Cole was a master with a thin brush: “I watched him take a number 2 ink-loaded brush to one of his “Plas” cover – or splashes – nice control, undulating line, all that feathering, slick, ‘finished,’ yet so essentially simple…” (Alter Ego 25, June 2003).

In his 1938 cartoon, however, Cole was still working on his brush and ink technique. The eyeballs of the characters in his Collier’s cartoon are black raisins and his line is nervous, jumpy. Nonetheless, his first Collier's cartoon has an air of freshness about it that goes beyond the visual style itself. The joke is genuinely funny and character-driven. We feel that we know this sweet, old-fashioned dowager personally and find it amusing that she thinks an airmail letter is an adventure.

It's interesting to note that the man who would become the creator of some of the sexiest cartoons for men's magazines ever drawn started out with a charmingly innocent cartoon featuring an elderly spinster. It's also worthwhile to note the details Cole has stuffed into this small, narrow cartoon: the silhouette portraits on the wall that bespeak of a graceful time of the past, the antique grandfather clock, and especially the adorable cat blending into the rug at bottom left -- very similar to Plastic Man's penchant for melting into a red rug with black and yellow stripes.

A sale to Collier's in 1938 was an auspicious achievement for any new cartoonist, including Jack Cole. At the time, Gurney Williams was publishing cartoons by such greats as Otto Soglow, George Price, Charles Addams, William Steig, Jefferson Machamer, Garret Price, Syd Hoff, Chon Day, Ted Key, and Frank Owen. Just about nine years earlier, Collier’s was where the great Rube Goldberg refined his invention cartoon, created in 1912 into his iconic cartoon series of overly complicated contraptions, “The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K.” One of these cartoons, which portrayed a self-operating napkin, became the art used for the 1995 United States stamp commemorating Goldberg (a later series of stamps, “DC Comics Superheroes,” featured two images of Plastic Man, neither of which were drawn by Cole - a raw deal, if you ask me).

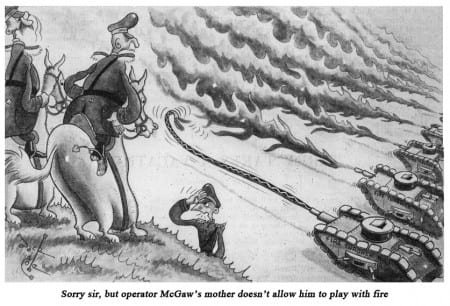

In July 1938, when the last issue of Circus the Comic Riot was on the stands with the last of Cole's sublime "PeeWee Throttle In Fuzzyland," the industrious Cole also had cartoons in that month's Boy's Life and Judge. The Judge cartoon presents a bland, asexual drawing of a nurse that is nothing like the intoxicating fantasy sirens of Cole's later work.

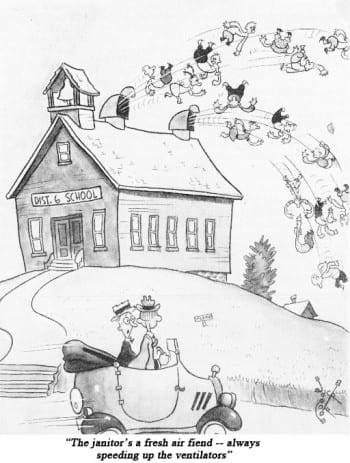

Cole's confident Boy's Life cartoon that appeared in the Septmeber 1938 issue shows a much more fluid approach, capturing a freeze-moment in a frantic scene -- a device that would become the hallmark of Cole's art. His wash technique had become much improved, as well.

Four months after Cole's first sale to Collier's ran, editor Gurney Williams published a second Cole cartoon, in the December 17 issue of Collier’s.

On December 30, 1938, the New Castle News trumpeted “three cheers and a great big cheerio for our friend Jack Cole … cartoonist supreme… again we see a piece of his work in Collier’s.”

By 1938, Cole had begun to gain some traction. He was selling regularly to Boy’s Life, Collier’s and Judge, where he placed cartoons in the July and September issues of that year. But even though the markets were prestigious, the money Cole was making from his gag cartoon sales did not begin to pay the bills.

Stuck in “Category C”

It is not so far-fetched to think that, if Cole had been able to stick with his regular gag work, he might have made a good living. The four-alarm fire cartoonist behind Smokey Stover, Bill Holman, whose packed, high energy screwball approach clearly influenced Cole, had left newspaper cartooning in 1931 to enjoy several lucrative years of selling gag cartoons. Holman’s work blazed through the magazines that Cole may have read as a teen. In a circa 1970s Millimeter interview with John Canemaker, Bill Holman paints a portrait of the career Jack Cole also pursued, and of the success that was possible:

“I started freelancing and things really started opening up. Judge was the first magazine in which my cartoons appeared. Jack Shuttleworth was the editor. We cartoonists made the rounds on Monday, rather than on Wednesdays, as was the case later on. I soon had about 30 markets and made a Hell-of-a-lot of money.”

Even though Holman’s gag cartoonist tapered off around the time that Jack Cole was just getting started, Holman’s statement explains one good reason Cole felt he needed to move to New York City (another being the only career opportunity for Cole in his home town involved working in a factory). In the 1930s, the American magazine gag cartoon market was centralized in New York City. Cartoonists would travel into the city on assigned days and make the rounds of various editor’s offices in Manhattan, showing rough sketches of their ideas. The editors would pick what they liked, sometimes with requested changes (“I like this, but make the clown a mailman and you got a sale.”). It seems probable that Cole met Collier’s editor Gurney Williams in person after he moved to New York City.

Seasoned career cartoonists like Jay Irving and Reamer Keller (also a steady contributor to Boy’s Life in the late 1930s) who proffered an established, recognizable (if bland) style and theme, had cartoons in virtually every issue of Collier’s in the late 1930s. In addition, they were often hired to produce cartoons for advertising – which probably paid significantly better than the gag sales. It was this career path that Cole had set out to traverse, with the same inner fortitude shown in his cross-country trek a few years earlier.

However, from another point of view, Cole’s initial scheme – the product of a young, inexperienced person - seems doomed to failure. In his 1946 book, I Meet Such People, Gurney Williams created four different categories of cartoonists. The Jack Cole of 1937-38 seems to fit into Category C: “the beginner with promise who might get somewhere some day, but who is generally too harassed by financial necessity… to make progress.”

Cole was indeed making progress, but it was too slow. The income from his gag panel sales, as promising as they were, was not enough to support the Coles. Jack needed a lifeline. In early 1938, he had begun to spend most of his working days sitting in a large room located on the fourth floor of an old warehouse on 23rd street, picking up rent and grocery money by selling his work for publication in the cheap colorful pamphlets called comic books. That summer, Action Comics #1 appeared with the sudden intensity of a lightning bolt, causing a surging wave in pop culture that would eventually alter the trajectory of Jack Cole’s career, and life.

Welcome to Framed!, my new monthly Comics Journal column that will look at many things comics-related (not just Jack Cole). Next month, since we're deep in the Cole-mine, I'll continue my in-depth look at the lost comics of Jack Cole, this time focusing on his early comic book work with the Harry "A" Chesler shop. In the meantime, you might want to check out my blogs, Cole's Comics and The Masters of Screwball Comics.

I was walkin' down the street mindin' my own affair

When two policemen grabbed me, unaware

He say, "Is your name Henry?" I says, "Why sure"

He says, "You the boy I've been lookin' for"

I was framed, framed, I was blamed, FRAMED!

~ Framed by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller (1954)

______________

Many thanks to Ger Apeldoorn for finding and sharing with me some of Jack Cole's lost comics, a few of which appear in this article. I especially appreciate Ger's kind support and encouragement of my work. Be sure to check his blog out for more comics goodness.