1.

The second issue of Derik Badman’s self-published MadInkBeard comic book (Spring 2012) is a collection of photocomics—comics whose images are photographs rather than drawings or paintings. Badman titles the entire issue “in the nature of navigation”, which nicely describes his photocomic aesthetic: the pictures Badman assembles into sequences read like a first-person account of an unseen observer navigating through various industrial and natural spaces. In “40.071619, -75.124485”, a wordless piece, there’s parallel movement towards two areas in a garden, one sunlit and one in shadow. Here is an example of the progression towards the light, from the point of view of someone (Badman himself?) walking towards sunshine:

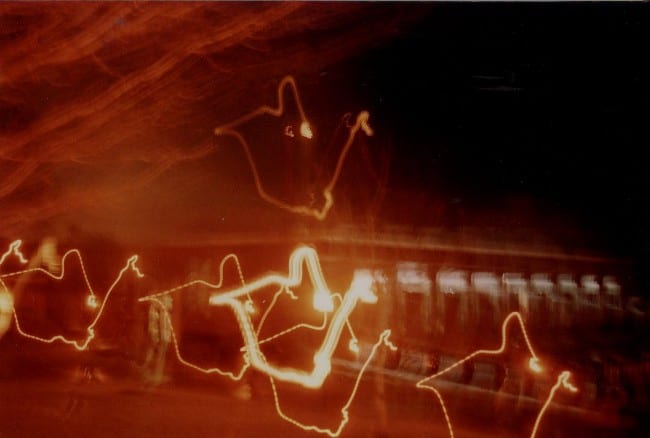

The piece immediately after “40.071619, -75.124485”, titled “Night Walking”, also feels like subjective sight: it’s a sequence of photos taken at nighttime of neon streaks and blurry headlights, reminding me of Stan Brakhage’s hand-held camera in Anticipation of the Night (1958).

In this issue of MadInkBeard, there’s also an essay by Badman about photocomics. Derik mentions popular examples—Harvey Kurtzman’s photo-based stories in Help!, Latin American fotonovelas, Guibert, Lefèvre’s and Lemercier’s The Photographer (2009)—even while pointing out the reasons that photocomics are marginalized by comics fans and readers:

Within the realm of comics, I don’t believe there is much respect for photographic works. In general, the world of comics has a long history of focusing on craft: a snobbishness about drawing skill and style as the primary factor in appreciation. Photocomics work against this traditional sense of craft. I also can’t disagree that most photocomics are pretty ridiculous, especially when attempted with genre material. The goofiness of the bad genre photocomics is partially because we tend to see photographs as images of the past and, as such, actors dressed in silly costumes just look like actors in silly costumes. (2)

After this bad news, Derik then lists a number of photocomics that he does consider worthy of attention, including books by Marie-François Plissart and Benoit Peeters, Chris Marker (the ciné-novel version of his famous short film La Jetée [1962]), Deborah Turbeville and Guy Bourdin. I’m grateful to Derik to discussing these photocomics, many of which I’d never heard of before, but after reading his essay, I wondered: is there an artist traditionally associated with American-Anglo comics culture who uses photos extensively in his/her work?

2.

In virtually all of the books he’s produced in the twenty-first century, Eddie Campbell has abandoned the nine-panel pages and pen-and-ink style that characterized Alec and From Hell in favor of new approaches to storytelling rendered in new media. In Batman: The Order of Beasts (co-written with Daren White and with “digital finishes” by Michael Evans, 2004), the art is a combination of ink, ink wash, and painted colors, and Campbell revealed at a 2008 San Diego Comicon panel that he always preferred to paint but that he drew his earlier comics in ink because of printing and budget limitations. Campbell has stuck to Beasts-style painted art for several subsequent projects, including the 19th-century crime drama The Black Diamond Detective Agency (“inspired by” an unproduced screenplay by C. Gaby Mitchell, 2007), the wittily self-reflexive The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard (co-written by Dan Best, 2008), and the naturalistic The Playwright (written by Daren White, 2010).

Possibly Campbell’s most groundbreaking recent book is The Fate of the Artist (2006), a whirling collage of painted art, extended prose segments, and photography. Fate is also an anguished chapter in the Alec autobiography, and the most obviously personal of Campbell’s recent works. In photographic sequences featuring (and ostensibly narrated by) his daughter Hayley, Campbell describes the onset of his brutal mid-life crisis after closing down his comic-book company in 2002. I suspect that Campbell’s relentless experimentation of the last decade has been fueled by that mid-life crisis, by an acute personal need to find a fresh artistic path. Campbell’s new art is at least partially inspired by the aesthetics of photography.

In many of his recent books, Campbell combines changes to his visual style with stories about the satisfactions and challenges of being an artist. Fate of the Artist is all about Campbell losing himself as a cartoonist, father and man; on the first full story page of the book, Campbell declares (in third person) that “the artist has come to despise his art, his self and his readers.” “You can all go to fuck,” he says to us while in bed, exhausted, lying in a pose that echoes Henry Wallis’ famous painting The Death of Chatterton (1856) and the rest of Fate is an assemblage of vignettes and narrative games that display the symptoms of Campbell’s mid-life crisis, including hypochondria and writer’s block. Fate ends with Campbell’s adaptation of an O. Henry short story, “The Confessions of a Humorist” (1903), where a successful humor writer, a twin for Campbell himself, grimly strip-mines his family and friends for ideas (“I became a harpy, a moloch, a vampire”). The humorist only finds peace when he quits writing and takes a new job as an accountant for a mortician, and it’s clear that Campbell wants a new job too: he’s tired of exploiting his family for material, tired of being a comic book auteur, tired of being.

Black Diamond is a more upbeat tribute to the power of art, particularly in the character of Sadie, an artist hired by the Black Diamond Detective Agency to draw an accurate portrait of John Hardin, a fugitive on the lam. By listening carefully and asking questions of people who’ve seen and spoken to the Hardin (“What was it about his eyes again?” “They were like my father’s, after the war. Sad, far away”), Sadie produces a perfect likeness of Hardin’s face, even though she has at that point never met the man. I read Sadie as Campbell’s surrogate in Black Diamond—her work reminds me of Campbell’s own job as a part-time court sketcher—and Sadie begins to work on the portrait only after her photographs of the crime scene (a train blown up by a bomb) refuse to yield the information the agency needs. Like David Hemmings’ character in Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), Sadie discovers that her photos of the train disaster are all “murky”: “Go in close and there isn’t a single recognizable object. Stand far enough back and it might as well be the lives of insects.” Sadie’s portrait, however, captures the essence of John Hardin, and Campbell suggests that the sympathetic conscience of the artist elevates art as a medium over photography.

Some of these ideas from Fate and Black Diamond reappear in The Playwright, the low-key tale of a middle-aged author, Dennis Benge, haunted by the fact that he is still a virgin. In the first chapter, White and Campbell tell us that the playwright “never wastes good material” that he can steal from his life and pour into his art—and is currently estranged from his parents because he wrote a screenplay based on the circumstances of “his older, retarded brother.” Benge is an updated version of O’Henry’s humorist, and his story ends in a way similar to “The Confessions of a Humorist”: when Benge is finally in a sexual relationship, when he gives up being (in O’Henry’s words) “a harpy, a moloch, a vampire” and fully commits himself to life, his motivation to write vanishes. In The Playwright’s last scene, as we see Benge settle down into bed with his woman, the wry third-person narrator notes that “the playwright has reached his conclusion…and he never writes another word.”

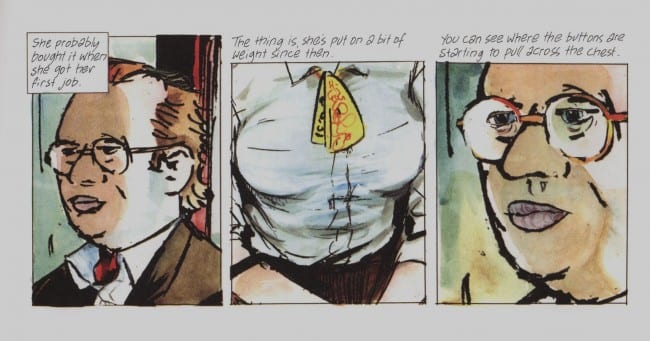

Campbell illustrates much of the playwright’s story in medium and long shots, but sometimes breaks up the steady progress of the story by repeating and enlarging key details of previous panels. Also in chapter one, during a scene where Benge stares at a woman on the bus, Campbell “zooms” in on both the woman’s chest and Benge’s face.

Lines grow thick and splotchy; Campbell moves from a “lives-of-insects” long-shot perspective to the close-up materiality of lines themselves, to the space where we begin to lose our sense of “recognizable objects.” Is Campbell again wishing for deliverance from a life devoted to art, and is he paradoxically scouring his own drawings for clues as to what a life without art might be?

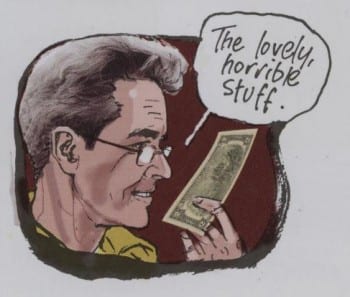

Campbell’s most recent book is The Lovely Horrible Stuff (2012), a two-part autobiographical treatise on money. In the book’s first section, Campbell talks about how money affects himself and his family; he revisits tropes from previous Alec stories (his insulting letters to deadbeat publishers, his tendency to mentally “leave the building” whenever financial discussions get too complex), even while he describes in awkward detail his anger when his father-in-law delays paying back money Eddie loaned him. The second section of Lovely Horrible chronicles a trip Campbell and his wife Anne took to Yap, a western Pacific island where large stones called Rai have traditionally been used as currency.

Open to any page of Lovely Horrible, and you’ll see photographs everywhere. In three panels on page 31, Campbell dreams about an alternate career as a “funny person on television,” a talk show “raconteur,” and the visuals are, appropriately, straight-up photos of Campbell as he sits in a chair, grinning. Elsewhere, and frequently, Campbell places hand-drawn characters against complicated yet unobtrusive photographic backgrounds, as in the sequence (pages 8-9) where Eddie visits his own fantasy version of the Café Guerbois and dishes with Will Shakespeare about the hassle of collecting debts. Sometimes Campbell mixes art and photography in more surprising ways, as in the several images throughout the book where he merges photos of his real hair with drawings of his face and profile.

Open to any page of Lovely Horrible, and you’ll see photographs everywhere. In three panels on page 31, Campbell dreams about an alternate career as a “funny person on television,” a talk show “raconteur,” and the visuals are, appropriately, straight-up photos of Campbell as he sits in a chair, grinning. Elsewhere, and frequently, Campbell places hand-drawn characters against complicated yet unobtrusive photographic backgrounds, as in the sequence (pages 8-9) where Eddie visits his own fantasy version of the Café Guerbois and dishes with Will Shakespeare about the hassle of collecting debts. Sometimes Campbell mixes art and photography in more surprising ways, as in the several images throughout the book where he merges photos of his real hair with drawings of his face and profile.

Campbell has also begun to “paint” in Photoshop, in order to trick the reader’s eye into seeing elaborately constructed combinations of art and photography as straight-up photos. A couple of months ago, in an e-mail, Campbell sent me two versions of an image, one large and one much smaller and roughly at the size it appeared in Lovely Horrible on page 81:

Campbell then explained these images: “I avoided using computer colouring until I figured out a way that I could use it like I’ve always used paint. Enlarged, that figure looks like this, but at print size the eye reads it as a photo (the actual photo of the background helps the illusion along). Understanding light and shade is the key to making it work. The disc and the other disc in the background were imported from another photo.”

Campbell’s Photoshop technique both extends and challenges the ideas about pictures and representation he presents in Fate, Black Diamond, and The Playwright. Fate is a collage of different image-making strategies—one page is a photograph, the next page presents three examples of Campbell’s Honeybee comic strip, etc.—and Lovely Horrible brings that collage aesthetic to the level of the individual panel, where Campbell splices together disparate photos, Photoshop “painting,” and hand-drawn marks into a unified composition. The panel only really comes together, however, at the proper scale, when Campbell (and the printing process) shrinks it down and prompts us to read the image as a photograph. The concern for scale exhibited by Black Diamond’s Sadie (her vacillation between “lives-of-insects” long shots and indistinct close-ups) and the blow-ups of The Playwright has been channeled in a new direction.

Yet it also seems that Campbell has reversed one of his earlier implicit arguments. In Black Diamond, Sadie’s portrait is more important to the case than her photos of the train wreck—art is a higher medium than photography—yet in Lovely Horrible, Campbell aspires to create panels that look like photos. Why? Perhaps because Campbell divorces his photos from their original contexts so thoroughly that they’ve lost any connection to the actual people and objects they initially recorded.

In the Yap section of Lovely Horrible, Campbell emphasizes that money is an abstraction, a metaphor for labor that often slips away from its original purpose to take on new associations and meanings. On page 57, Campbell mentions that the Rai replaced a more unwieldy abstraction (decorative carvings of various shapes and sizes) with the discs, and later discusses a specific incident that has fascinated Western economists. The first page of Campbell’s version of the incident:

The stone sank in the water as it slipped off a raft in the middle of a storm. According to anthropologist Furness, “It was universally conceded that the mere accident of its loss was too trifling to mention…and that a few hundred feet of water offshore ought not to affect its market value. The purchasing power of the store remains as valid as if it were leaning against the owner’s house.”

Campbell summarizes how various commentators have interpreted the Rai in the sea. For John Maynard Keynes, it was a perfect example of (in Campbell’s words) “the kind of abstraction that typifies modern finance”; Milton Friedman drew similarities between the incident and a 1932 exchange of gold between France and the United States; Michael F. Bryan argues that the stone money is identical to contemporary coin money; Dror Goldberg denies that the Rai are truly money at all; and Campbell himself asserts that many Rai “have an aesthetic dimension,” like sculptures.

In other words, the Rai are slippery, polymorphous signifiers, just like photographs. Like money, photos have a basic value—they are a metaphor for a slice of the real world at a specific time and place—but they are also representations that, over time, take on unintended, non-referential, diverse and sometimes contradictory ideological and aesthetic meanings. In Lovely Horrible, Campbell is able to assemble images that look like photographs only by treating the actual photos that he splices into his collages as signs untethered to their referents, as raw material that he’s free to alter at will. Is it Campbell’s desire to leave art behind that attracts him to photographic aesthetics, and to the creation of dense, painted, Photoshopped collages that nevertheless look “real”?

3.

I teach film history and theory, and I assign to my Introduction to Film students what I call a “photography assignment,” a simple task designed to inform them about the photographic basis of pre-digitized motion pictures. I got the idea for my photography assignment in 1999, while re-watching one of my favorite movies of the 1990s, Smoke (1995), directed by Wayne Wang and scripted by Paul Auster. Early in Smoke, there’s a scene where cigar-store owner Auggie Wren (Harvey Keitel) shows his artistic “life’s work” to novelist and widower Paul Benjamin (William Hurt). Auggie’s project: he’s taken a picture of the exterior of his cigar store every morning for the last ten years, and assembled the resultant thousands of pictures into photo albums. During the scene, Paul leafs through several of these albums, stumbles across a photo of his dead wife inadvertently taken by Auggie, and has a cathartic cry. Here’s a section of the scene, from YouTube:

I like how this scene captures photography’s representation of the real world. Susan Sontag famously argued that a photo is in some measure “a trace, something directly stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.” Most photos capture the actual presence of people and objects in a particular place at a particular time, and retain a “material vestige” (as Sontag puts it) of these people and objects in a way that paintings and other visual representations can’t. Paul discovers a trace of his dead wife in Auggie’s photo album; Auggie’s project as a whole is the collection of such traces into a long-term visual history that captures the reality—or at least one version of the reality—of his “own little spot.”

Of course, I can’t expect my students to keep a photographic record as thorough as Auggie’s, so I came up with a different, but related, assignment that I’ve given every semester since 1999 to everyone who takes my Introduction to Film class. The assignment is this:

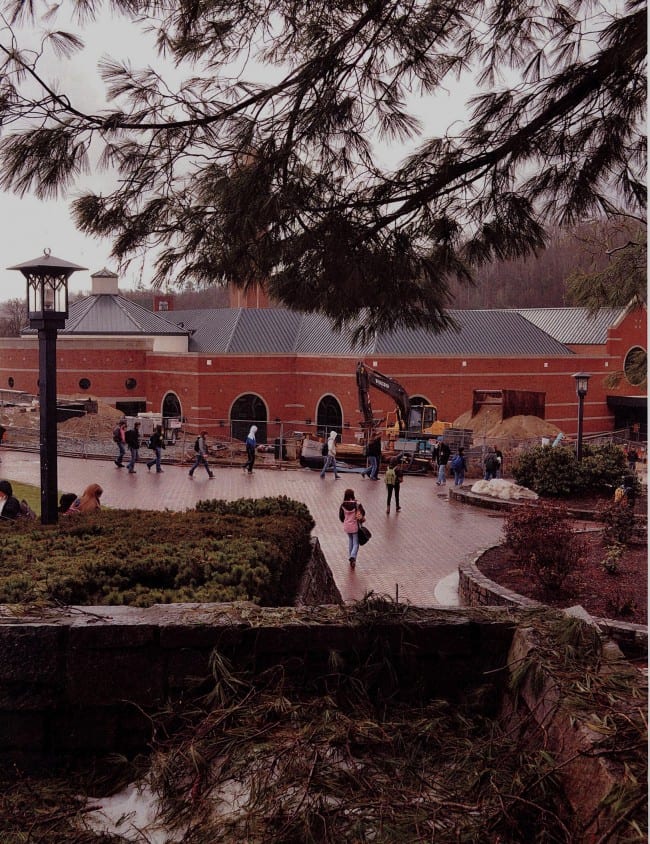

Get a camera and take a picture while standing anywhere you want on the flight of stairs in front of the old Belk Library, the building with the bell in front of it. What is included in the picture (people, buildings, grass) is up to you. Then immediately write down the date and time (to the minute) that you took the picture. Get a hard copy of the picture made, and give it to me, along with the information about the date and time, by the due date.

Why am I having you do such a simple assignment? We’ll use your photos as part of our in-class discussions on framing, film stock, and the photographic basis of “motion pictures,” but I also want you to realize that taking a photo means capturing a time-contingent part of the real world. As Yoko Ono—an important avant-garde filmmaker, and not just John Lennon’s widow—once remarked, film is “like wine. Any film, any cheap film, if you put it underground for fifty years, becomes interesting. You just take a shot of people walking, and that’s enough: the weight of history is so incredible.” (The above quote is from Scott MacDonald’s interview with Ono in A Critical Cinema 2.)

After we discuss the photos, I’m going to be like Harvey Keitel in Smoke, and mount them in an album that I’ll donate to Belk Library after I retire from teaching. (I also hope to put the pictures up on Flickr soon.) Perhaps students in fifty years will drink the wine of your pictures and understand a little better the history of our campus and its students.

Although we haven’t produced a day-by-day chronicle of our own “little spot,” my students and I do produce dozens of photographs—taken twice yearly—of the area in front of the old Belk Library on the campus of Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. And we’ve done so for the past thirteen years, even though time has changed the particulars of the project somewhat. In 1999, for instance, most students took their pictures with traditional emulsion cameras, but in 2012 virtually all of them handed in digital photos. In addition to following the changes in architecture and undergraduate fashion in our corner of the world, our project also tracks the rapid conversion of photography from chemical to digital technology.

Early on, the project also became personal to me. In the very first batch of photos I received, a student named Teresangela Schiano handed in a picture of two mothers walking two young children in strollers around the university quad. One of the mothers was my wife Kathy, and one of the kids was my son Nate, even though T didn’t know either of them; it’s a bizarre echo of the Smoke scene, though I’m happy to report that my wife is alive and healthy. There is something uncanny and poignant, though, in looking at Nate as a toddler, riding in his stroller, and then seeing him today, almost sixteen years old, now taller than me and smarter in so many ways. The weight of history is so incredible.

I store all the student pictures in a series of photo albums on a shelf in my office. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud defines the comics medium as “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the reader.” Not that McCloud is the final word on the nature of comics, but…have my students and I inadvertently assembled, in the pages of all those photo albums, a long-form comic book?