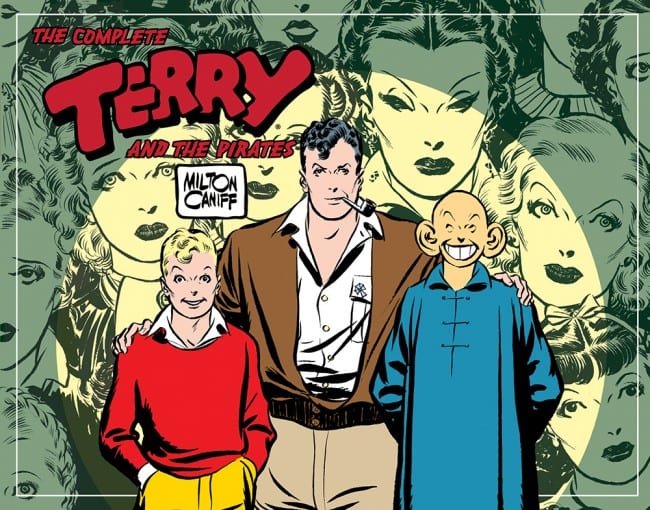

The Library of American Comics, which has released excellent editions of comic strips Terry and the Pirates, Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy, as well as focused biographies of artists including Alex Toth and Noel Sickles, recently released its 75th book. The quality of both the reproduction and the ample historical material and essays included in each book has been consistently excellent. Each essay in each of those hefty volumes reveals some new facet of comics history, including gems like a mini-biography of Don Moore, the writer of Flash Gordon, or, as in the most recent volume of Steve Canyon, an in depth look at Milton Caniff's use of models. Anyhow, it seemed like a fine time to correspond with LoAC founder Dean Mullaney and associate editor Bruce Canwell.

The Library of American Comics, which has released excellent editions of comic strips Terry and the Pirates, Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy, as well as focused biographies of artists including Alex Toth and Noel Sickles, recently released its 75th book. The quality of both the reproduction and the ample historical material and essays included in each book has been consistently excellent. Each essay in each of those hefty volumes reveals some new facet of comics history, including gems like a mini-biography of Don Moore, the writer of Flash Gordon, or, as in the most recent volume of Steve Canyon, an in depth look at Milton Caniff's use of models. Anyhow, it seemed like a fine time to correspond with LoAC founder Dean Mullaney and associate editor Bruce Canwell.

You've reached your 75th LOAC release. In terms of concept and execution, what do you think your biggest successes have been? What about your failures? Are there titles that flew under the radar for you?

Bruce Canwell: I'd say our biggest successes have been: [A] discovering how Dean and I -- and subsequently, we and later additions to the LOAC team -- were so closely in sync as to what we wanted to produce in terms of content, design, style, and scholarship, and [B] being lucky enough to find an audience that, on balance, is in tune with our sensibilities.

I'd say our major failure has been the same one shared by all other players in this arena: we've all created high-quality collections of exceptional comic strips, but none of us have found a way to grow the audience so these books sell in the big numbers the material deserves.

Dean Mullaney: The fact that we have seventy-five (and counting) books in the imprint is, in and of itself, our biggest success. Seventy-five books in any imprint is impressive; when you look back at the Hyperion line of strip reprints in the late 1970s, Bill Blackbeard managed to publish twenty-two titles, one third of LOAC’s current output. I also like to think that we have upped the ante in terms of strip restoration so that modern readers have a better sense of what the original strips were supposed to look like

For me personally, the biggest success has been to bring Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates back into print, with the Sundays in color and with Bruce’s phenomenal essays that place the strip in its historical context. Each of the six volumes has gone through multiple printings and continues to sell.

If by “under the radar” you mean books that we feel should have received more attention than they did…I’d say King Aroo, the Chuck Jones book, and the Otto Soglow collection. It’s disappointing to note that in this day of bloggers and reviewers trying to constantly post new items ahead of the curve, detailed analysis tends to fall by the wayside. And let’s be realistic, in a crowded market, a more obscure “art house” strip like King Aroo or Barnaby needs perceptive bloggers and reviewers to help spread the word. And that’s not really happening.

If by “under the radar” you mean books that we feel should have received more attention than they did…I’d say King Aroo, the Chuck Jones book, and the Otto Soglow collection. It’s disappointing to note that in this day of bloggers and reviewers trying to constantly post new items ahead of the curve, detailed analysis tends to fall by the wayside. And let’s be realistic, in a crowded market, a more obscure “art house” strip like King Aroo or Barnaby needs perceptive bloggers and reviewers to help spread the word. And that’s not really happening.

I've often wondered during the reprint "boom" whether or not there's an identifiable audience, beyond libraries, buying and responding to this work. Have you been able to identify one?

Canwell: Certainly -- more than one, in fact! I suspect all the players in the market, not just us, benefit from the same audience. The long-time devoted collectors of comic strips -- call them The Sons of Bill Blackbeard -- are livin' the dream at this point in comics publishing history. Many readers who were buying the first wave of comic strip reprints from the likes of Kitchen Sink, Fantagraphics, Eclipse, and NBM are upgrading their collections with the new editions being published today.

We also see an audience segment smaller than The Sons of Bill Blackbeard but still sizeable enough to be of note: folks who find their long-time interest in the latest comic books is fading. They're shifting to strip reprints, finding the wealth of great material that's available, and rekindling their love of comics. (I have an affinity for this group, because that's the exact path I walked during that first wave of strip reprints in the 1980s.)

The Sons of Bill Blackbeard -- the libraries and schools -- the comic book fans who become comic strip fans -- the parents who seek appropriate reading material for their kids and discover Little Orphan Annie or the Gottfredson Mickey Mouse books or (for the more precocious reader) King Aroo ... all of those are important clusters of demographics for our little corner of the industry.

Mullaney: I’d add another key segment to that group: comics professionals and would-be comics professionals who want to learn from and be inspired by the master cartoonists of the past. It’s all fine and dandy to have heard that Caniff, Herriman, Raymond, Segar, Foster, King, et al were great, but unless their works are reprinted, it’s just talk. You need to SEE and READ the work -- and we now have an unprecedented opportunity to study these classic strips.

Mullaney: I’d add another key segment to that group: comics professionals and would-be comics professionals who want to learn from and be inspired by the master cartoonists of the past. It’s all fine and dandy to have heard that Caniff, Herriman, Raymond, Segar, Foster, King, et al were great, but unless their works are reprinted, it’s just talk. You need to SEE and READ the work -- and we now have an unprecedented opportunity to study these classic strips.

Further, individual titles can broaden our market and reach a new audience. For example, Bloom County is our best-selling series to date because it captures people who aren’t specifically strip fans, but are Bloom County fans. Same goes for Star Trek – our best information indicates that the Star Trek strip book is being bought primarily by Star Trek fans, not strip die-hards.

Now, will Bloom and Trek fans start buying Li’l Abner and the Gumps? Probably not, but the success of any book in the line helps the entire imprint – not merely because it makes money but because retailers and wholesalers look more favorably on an imprint that has certified “hits.” There are a lot of marketing and sales factors that come into play and are not of interest to fans. And not important to them, either. It’s “Inside Baseball” kind of stuff that I need to be aware of, yet is irrelevant to the reader.

Is there a place for a "best of" Dick Tracy or Annie? Is that something that's even possible with those strips? I've wondered if the seriality of the books is an issue (as well as being a virtue, of course).

Canwell: There are definite challenges to doing “Best of” collections, especially for a strip like Little Orphan Annie, where continuities could run for the better part of a year. Still, every problem has a solution — our first and so far only foray into softcover publishing is a Best of Dick Tracy. I think it’s a great little “Whitman sampler,” a way for someone totally unfamiliar with Tracy get an idea of what he’s all about. I wish something like this had been out there when I was first deep-diving into the strips back in the ’80s!

And to that end, I wonder that the next step is? Do you plan to start new series? Or stay entrenched with the numerous strips you have going now? If the latter, what is your criteria for inclusion in the LOAC? With so many classics covered already, how do you begin to decide on secondary titles?

Canwell: Yes; we've had new releases every year The Library of American Comics has been in business. Why would we stop now? And as long as there is audience demand, why would we stop producing Steve Canyon or Li'l Abner or Skippy? Our criteri is the same as it ever was: projects that appeal to Dean and me, that we believe will be fun to produce AND fun for the audience to read; informative, too, one hopes. One of the big disconnects in our society is the notion that "learning" and "fun" should be separate things. Alex Toth's life is a STORY, as is George McManus's, or Milton Caniff's -- our task is to bring that story to life in a way that informs and entertains in equal measure, because to us those two qualities go hand-in-hand. The timeless value of the material, of course, speaks for itself. "... how do you begin to decide on secondary titles?" Probably by not worrying about meaningless labels like "secondary titles." Who decides what is "secondary," anyway? And how many other strata have these faceless arbiters created?

Mullaney: There’s no single criterion for what strips to reprint. Sometimes one of us has a particular favorite and we’re in the position to make it happen. Our long-term goal is to present a wide variety and a fair representation of strips that, together, tell the overarching history of newspaper strips. And we obviously need to be aware of commercial considerations. We’ll give some strips the complete treatment (Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie), while others—Bringing Up Father—will get the best years in sequential order treatment. Other strips might get a one-shot.

I doubt if there are any (or many) long-running series we’ll add to the line. But then again, new opportunities can come along unexpectedly, as in our getting the license from DC for the Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman strips. These series alone will add nearly two dozen titles to LOAC over the next few years. I’m current penciling in the schedule for 2014 and 2015 and trying to find slots for all the books we want to do!

I wonder if you can write a little more about the differences in approach between say, Soglow/McManus and Gray/Caniff. Beyond commercial considerations, do you think some strips are simply better than others in terms of the experience of reading the whole run?

Canwell: It’s tough to make a broad generalization here, I think, because several factors come into play. A strip like Caniff’s Terry is so short, relatively speaking, that certainly it rewards being read from start to finish. A series like Bringing Up Father began in the comics’ first blush and has McManus’s name attached to it until the middle of the 20th Century: the concept stays the same throughout, yet in terms of format, look, and pacing the 1910s BUF is significantly different from the 1940s BUF. Would those early strips be of interest, given the art is far less layered and detailed, and Maggie & Jiggs’s routine has now been played out by TV imitators like Ralph & Alice Kramden, Archie & Edith Bunker, and Al & Peg Bundy (among others)?

Then think of how many strips got squeezed in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s by the shrinking real estate allotted to the comics page. Some series retain their appeal even in those cramped quarters because their creators still have interesting stories to tell or things to say (Steve Canyon, Li’l Abner), others less so.

Have there been any strips on your wishlist that just don't make the grade, commercially? And if so, are there potential solutions to that problem?

Mullaney: We've got a list a mile long that's probably not much different from the list my old pal Kim Thompson has made at Fantagraphics. Plus, we all have personal faves that are totally uncommercial; for example, I'd hung up on Fay King's art, but aside from Cole Johnson, Trina Robbins, and me, I don't know if anyone else would care!

One solution to the problem is our new series, LOAC Essentials. By offering a year's worth of dailies (instead of 3 years’ worth), we can keep the price down so readers will be more willing to try something new. There aren't a lot of readers, for example, clamoring for a gigantic $50 volume of the Gumps -- but by presenting a shorter book, I think we'll get those readers hooked so they'll want a second Gumps storyline. We'd like to take similar approaches with other strips. For example, Bruce wants to edit a Cap Stubbs and Tippie book, I'm researching a top-notch Winnie Winkle continuity, and Jared Gardner remains hung up on Minute Movies.

You're about to embark on a Russ Manning series. I'm fascinated with the relationship between Toth, Marsh and Manning, and Manning's initial emergence from ERB fandom. How do you see the aesthetic relationship between Toth and Manning? Do you see a "California" school there? Were they in contact much?

You're about to embark on a Russ Manning series. I'm fascinated with the relationship between Toth, Marsh and Manning, and Manning's initial emergence from ERB fandom. How do you see the aesthetic relationship between Toth and Manning? Do you see a "California" school there? Were they in contact much?

Mullaney: The question of whether or not there was/is a "California school" is interesting. Regardless, there were certainly enough comics artists who migrated west or were native born.

Alex was a great admirer of Marsh's although I wouldn't say Marsh was an influence on him. I also don't recall Toth having anything except a peer to peer relationship with Manning. Dan Spiegle (who remains one of my all-time favorites) also seems to be a singular talent. One could argue that Toth's, Marsh's, and perhaps Spiegle's influence independently may have created a California school. Manning, of course, was influenced by Marsh and to a lesser degree by Toth; Manning, in turn, begat Dave Stevens, and on and on. The entire notion of a California school gets further complicated by the migration of East Coasters who were looking for sunshine and some Hollywood paychecks.

One point of debate in recent years is compensation for the estates of the artists involved. Do you have a stance on this?

One point of debate in recent years is compensation for the estates of the artists involved. Do you have a stance on this?

Canwell: I would hope our stance is obvious, first by our statement of principles on page 325 of Genius, Isolated, page 349 of Genius, Illustrated -- "Although some of Alex Toth’s earlier comics work may legally be in the public domain, there are some rights more important than legal ones. We ask everyone to respect Alex Toth’s memory and the moral rights of his children as the beneficiaries of his work. We urge those who wish to reprint any of that earlier work to contact the estate for permission: http://www.tothfans.com." -- and second by the fact we operate in a way that proves we apply those sentiments across the board, not just to Alex Toth and his heirs.

Mullaney: In fact, I first met Alex when I let him know that I’d be paying him money to reprint some of his public domain Standard comics. I started in the comics business in 1977 with the expressed purpose of establishing creators’ rights as the norm in the industry. I’m not going to pass judgment on other publishers/editors who don’t pay creators or their heirs for public domain work; that’s their call.

With long-running strips, it’s a little more complicated because anything that premiered in the early 1920s and earlier is public domain. Yet if the strip continued for a long time (Gasoline Alley comes to mind), at some point you hit a brick wall when the strips are still under copyright by the syndicate. So you can theoretically publish the early years and find heirs to pay, but once you get to the copyrighted material, you’re either paying double royalties (the syndicate AND the heirs) or just the syndicate.

The "moral rights" of the Toth estate: Can you expand on this? What are those rights, in your view, and how do they dovetail with the idea of public domain work?

The "moral rights" of the Toth estate: Can you expand on this? What are those rights, in your view, and how do they dovetail with the idea of public domain work?

Mullaney: Those rights are what we, as individuals, make them. The issue is totally separate from legal rights. From a publisher's perspective, if I want to reprint Alex's Zorro comics, I need to pay a licensing fee/royalty to John Gertz/Zorro Productions, who owns the trademark to the character and the copyrights to those stories. If, on the other hand, I want to reprint Alex's comics for Standard or Lev Gleason, the work is apparently in the public domain, so no licensing fee or royalties are due. If the original publisher failled to register or renew the copyright or that publishing entity no longer exists, anyone is legally free to reprint the stories. In the course of my long career in comics, I have made the personal decision that -- in the case of public domain comics in which there is no rights holder requiring a fee or royalties -- I would pay the artist or the artist's direct heirs. I still have letters of appreciation from Jerry Siegel, Jack Katz, Reed Crandall's sister, Ellie Frazetta, and other creators whose work I reprinted in the 1980s and 1990s and for which I paid them.

These "moral" rights run parallel to a previously obscure part the 1976 Copyright Act, which allows artists, under specific circumstances, to reclaim the rights to their work after 35 years. The intent of the law is to allow creative people a second chance to own material they sold to a publisher earlier in their careers when they may not have had fair leverage. I think we can all agree that very few comics artists in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s understood what they were signing away – or even IF they signed anything away. It seems to me that if we are in favor of Siegel, Shuster, and Kirby trying to reclaim their rights, then we should similarly should pay them for reprinting that earlier work. In my book, it's all the same thing.

With your recent deal to release DC character comic strips and IDW's Artist Editions, do you see any hope in larger companies allowing other publishing entities to more aggressively publish work that is more or less trapped behind corporate copyrights? Here I think of Meskin, Cole, Maneely, and, of course, Toth, whose DC work is represented in Genius Illustrated mostly via original art, as opposed to the final (printed) work. It is the only real absence in Genius Illustrated.

Mullaney: I can’t speak to the Artists’ Editions because we have nothing to do with them; they’re produced with great finesse by Scott Dunbier at IDW. Whether the larger companies such as Marvel and DC will license their copyrighted material to other publishers, who knows. It’s a question best directed to them.

In the Toth books, the reason I chose to reprint most of his DC work from original art rather than from printed comics had nothing to do with copyrights. As an editor/designer, I believe the original art best represents Toth’s intent, and it’s what Toth fans want to see. If this were a book of straight reprints, I’d have used printed versions. But the Genius series is part bio/part art book; as such, we wanted to stress the art. Plus, we were fortunate enough to find some very generous art collectors willing to loan the valuable art!

Speaking of original art -- what is your philosophy on original art vs. printed comics. When the work was printed in color, do you feel the image loses something as original art? Was Toth drawing for color, do you think?

Canwell: Isn't this like asking, "When the ground beef is cooked up as a hamburger, does it lose something by not being served as steak tartare?" It's still pretty tasty either way, isn't it? As for Toth drawing for color — an intellect as keen as Alex's would always keep the end result in mind as he worked, but remember [A] he was color-blind, so his own color sense was far from impeccable and [B] he knew what the coloring process was for comics during his heyday, and he knew how often it produced bad results.

Mullaney: Whether or not the image loses something as original art depends wholly on what the work is. I’m reminded of Alex’s Zorro comics for Dell, which for many of us was our first encounter with his art. I reprinted those stories two decades ago in B&W – with new tones added by Alex. Were they drawn “for color?” Yes, but the coloring sucked. Do they look better in B&W? Yes. Do they look better still in B&W with Alex’s new tones? Absolutely.

Mullaney: Whether or not the image loses something as original art depends wholly on what the work is. I’m reminded of Alex’s Zorro comics for Dell, which for many of us was our first encounter with his art. I reprinted those stories two decades ago in B&W – with new tones added by Alex. Were they drawn “for color?” Yes, but the coloring sucked. Do they look better in B&W? Yes. Do they look better still in B&W with Alex’s new tones? Absolutely.

I could argue the other way for, say, Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four. Sometimes it’s a matter of personal preference, but in Toth’s case, in my opinion, his work ALWAYS looks better in B&W.

I could argue the other way for, say, Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four. Sometimes it’s a matter of personal preference, but in Toth’s case, in my opinion, his work ALWAYS looks better in B&W.