Welcome to the fourth iteration of High-Low, a column that's run across a variety of different websites and with different purposes. This version will be a monthly column that focuses on minicomics and small press comics. Roughly speaking, that means anything outside of mainstream book publishers: Fantagraphics, Drawn & Quarterly, Dark Horse, etc. I'll still be reviewing such books on a weekly basis for the Journal as well as once a week on my old High-Low blog. Feel free to contact me for questions at tmc (at) duke (dot) edu. I will review any minicomics or small press comics that come my way; mail them to:

Rob Clough

507 Dupree Street

Durham, NC 27701

*********

There's an odd paradox currently at work in the world of comics publishing. As the market and distribution points for comics grows smaller, there seems to be an increasingly large number of small boutique publishers sprouting up. Koyama Press, 2D Cloud, Little Otsu, Secret Acres, NoBrow (from the UK), Alvin Buenaventura's new Pigeon Press, Zak Sally's La Mano, and Tom Kaczynski's Uncivilized Books are all examples of such publishers setting up shop in the last three years or so. Their books are printed in small numbers and generally fall into one of two categories: lovingly crafted art objects or more cheaply made comics in the vein of zines or old alt-comics. The goals of publishers like these are simple: to champion the work of artists they find meaningful, and to do it without losing their shirts. No one's going to make a living off of these comics, but they're probably not going to go broke, either.

These comics don't need bookstores and don't need Diamond to make it out into the world. Comics that belong to the art-object or zine-object camps thrive on the same sort of small national network of shops and social connections that independent rock bands survive on. Given the rise of small, regional comics shows, alt-cartoonists are even doing the same sort of tours to raise money and sell merchandise that indy rock bands have made a staple of their existence.

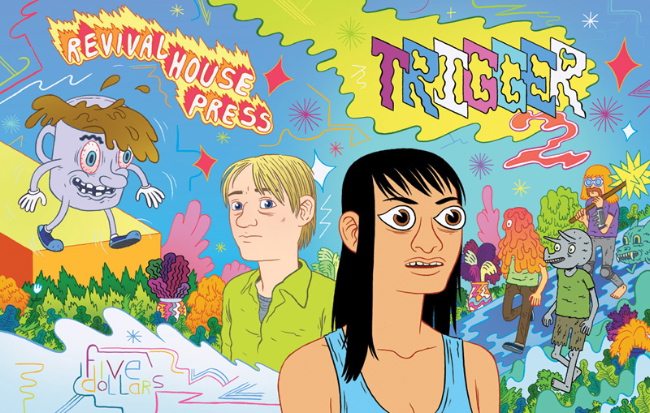

The comics from Portland's Revival House, published by Dave Nuss, fall firmly into the zine camp. With full-color covers and black & white interiors on cheap paper, these feel like 1990s artifacts. The editing is fast & loose; immediacy is the thing here. These are comics meant to be read, not held or stared at. The nature of comics like Trigger and Everything Unseen seems to lie somewhere between mainstream comics and outsider art. Artists Mike Bertino and Drew Beckmeyer both have one foot firmly planted in the world of fine art; for Beckmeyer, this is his first real foray into comics.

Of the two artists, Bertino is more polished, his drawings and stories (as noted in my review of the first issue of Trigger) resembling a cross between Ted May's and Ron Regé's. Perhaps Matthew Thurber is an even better comparison, given the occasionally grotesque nature of Bertino's character designs. This one-man anthology has the playfulness and occasional genre interests of May mixed with Thurber-like weirdness. That said, the quirkiness of Bertino's sense of humor is certainly its own unique entity. For example, "Goo Pants" combines fantasy elements, slice-of-life humor, and crude gags as it follows a young man and his magic pair of pants. His problem is that the pants are profane & inappropriate, growing ever more dissolute before the protagonist finally burns them in a garbage can. Bertino's clear, thin line is perfect for this cartoonish tale; the image of a pair of pants with bulging eyes and jagged teeth is at once hilarious and unsettling.

The second episode of the serial "Grown-Ups", which follows a young teacher trying to learn the ropes as he moves into a new position, is another clear-line success. Bertino is quite skilled at juxtaposing idealism and sleaze for comedic effect, and this story emphasizes that divide in moments that pop out at the reader. Bertino has a way of subverting reader expectation so as to generate some funny surprises, though he doesn't go quite as far as Ted May would in terms of injecting fantasy elements into these stories. For example, the young teacher, Conrad, is all about trying to reach at-risk youth by transforming history into a sort of group storytelling exercise. It's his narrative, for the most part, but the reader is jarred (as is Conrad) when an African-American teenage girl shocks Conrad by talking about older men, and making up an excuse to get out of class. Talking to her boyfriend about it later, he's a bit taken aback when he's told that it "seems like you're following me around." The after-school special narrative in Conrad's head gets completely turned around when he spots the girl driving around with a teacher colleague—one who had earlier gotten him drunk and tricked him into picking up a hooker. Told from the point of view of a young, idealistic teacher who is hopelessly out of touch, this story makes an interesting companion piece to the Jeff Wilson/Ted May series of true high school stories, Injury Comics, which blows up high school angst and adventures to comically operatic levels. Wilson and May go over the top with moments of sensitivity, while Bertino uses more restraint until he uncorks a surprise.

The final piece in this issue, "The Biggest Banger", is the most predictable in its outcome and thus its weakest. It's a Thurber-flavored science-fiction story (lots of wavy lines on its alien characters) in the mold of "serious" sci-fi, with all the thinly-disguised moralizing that often implies. It's the story of a group of aliens traveling for years through space, looking for a new planet to colonize & terraform. Once a a likely candidate is found, there are the usual debates about the ethics of destroying a planet. Bertino turns the scenario on its head by introducing humans as the savage, publicly defecating, sub-idiotic pets of the aliens, who then up inheriting and populating the Earth after their alien masters accidentally manage to destroy themselves. You can see that punchline coming, which blunts its effectiveness, but Bertino sells it with enough scatological brio to make it funny. With these three short stories, Bertino crafts perfectly accessible quirky comedy, the sort of alt-comics humor that would have been required reading in the early '90s. As with May's comics, Trigger has an almost nostalgic quality, leading to a familiar experience as a reader in terms of tone and style of humor. Its appeal lies not in its originality but in its execution.

Drew Beckmeyer's Everything Unseen is very much Trigger's opposite. It's a choppy, sloppy book with unsteady lettering and low production values. It's also a hilarious, sprawling epic whose style is reminiscent of Dash Shaw and Gary Panter. This is a story about religion, class, and identity, framed in a dystopian future. Beckmeyer's take on comics is a counter-intuitive one; he does a lot of things "wrong" in this comic. His pages are frequently text-heavy and his word balloons are awkwardly placed. His line is often smudged, and he flips from pages with highly decorative touches to bare-bones storytelling. Beckmeyer doesn't flow from transition to transition in his story as much as he suddenly lurches.

Somehow, all of this manages to work, because of the bizarre universe Beckmeyer creates and his relentlessly quirky sense of humor. The entire world of this book is based on a single idea: that people start to discover that they are born with seven doppelgangers. The extrapolation of this notion is that whenever a person meets one of his own doubles, it inevitably leads to a bad end--often rape or murder. The result is a series of internment camps where each person is assigned a caste order based on one's doppelganger status. More shades of Matthew Thurber arise with such odd touches as lower caste members' hands turning into rats when they touch the holy water the higher castes bathe in, and their faces melting when they see higher caste members sans their sheet coverings.

Somehow, all of this manages to work, because of the bizarre universe Beckmeyer creates and his relentlessly quirky sense of humor. The entire world of this book is based on a single idea: that people start to discover that they are born with seven doppelgangers. The extrapolation of this notion is that whenever a person meets one of his own doubles, it inevitably leads to a bad end--often rape or murder. The result is a series of internment camps where each person is assigned a caste order based on one's doppelganger status. More shades of Matthew Thurber arise with such odd touches as lower caste members' hands turning into rats when they touch the holy water the higher castes bathe in, and their faces melting when they see higher caste members sans their sheet coverings.

Everything Unseen is very much an episodic book, with each section providing a definitive narrative and emotional conclusion to the action we've just seen. The first chapter briefly sets up the world, including our protagonist's role as a camp drink server (on all fours, carrying a barrel around on his back). It establishes Beckmeyer's off-kilter style, the frequent digressions and the mix of surreal humor and dead-serious hero's journey. The second sets the hero's escape from the camp into motion, as he's inspired by a hip but indifferent vision of the angel of death in a dream. This was the funniest chapter in the book, allowing Beckmeyer to dig deep into camp life (including a mandatory group tap-dancing performance to amuse the higher caste members), while pushing the hero past the point of no return. In the third chapter, the hero meets one of his doppelgangers (named Charles Grodin), and eventually betrays him to police who are searching for him. The book ends as our hero is starting to feel the effects of guilt and a burgeoning existential crisis, forced to deal with a world he doesn't understand while finding that he's starting to enjoy the possibilities it provides him.  There is perhaps a bit of awkward suddenness in the way Beckmeyer so obviously delineates both the action and the hero's emotional state from chapter to chapter, and that might be a reflection on his relative inexperience as a storyteller. That said, the book's appeal lies in its quirks—not its plotting.

There is perhaps a bit of awkward suddenness in the way Beckmeyer so obviously delineates both the action and the hero's emotional state from chapter to chapter, and that might be a reflection on his relative inexperience as a storyteller. That said, the book's appeal lies in its quirks—not its plotting.

Occasionally Beckmeyer eschews drawings altogether and throws in a flow chart. On other pages, the drawings look like diagrams, and look like they were drafted, instead of drawn freehand. On one page, images are used as footnotes. Beckmeyer's weird lettering blends into his images, almost like a literal example of comics-as-poetry, making each page interesting to look at even when they're dominated by text. Due to the strangeness of the imagery, the solemnity of the text, and the sheer wackiness of ideas, Everything Unseen feels like someone's attempt at imagining a new holy text of some kind. Like any good sacred writing, it's got sex, violence, panoramic parade scenes, and "non-alcoholic root beer margaritas with ice cream atop." It's at once bewildering and delightful, and I'm eager to see how far Beckmeyer takes his new mythology.