TCJ interviews tend to break the Internet. As such, due to the length of this interview, it's been broken into two parts. From The Comics Journal #202 (March 1998). Here is Part 2. And you can click here for a selection of letters to TCJ about the interview.

Kevin Eastman’s career — odyssey is more like it — is probably the most fascinating, tumultuous, and farcical in comics history. As everyone knows, Eastman co-created, with his collaborator Peter Laird, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in 1984. The series took off almost immediately and became a global licensing bonanza — with innumerable kinds of merchandise as well as three feature films — making the rather bewildered young men millionaires practically overnight. In this interview, Eastman describes the economic, legal, and emotional roller-coaster ride that followed the Turtles’ success, but the centerpiece is certainly Eastman’s candid perspective on Tundra, the alternative comics company he founded with Turtles money in 1990, which he collapsed into Kitchen Sink Press in 1993. Tundra was certainly, not to put too fine a point on it, the biggest and most absurd (as well as the most idealistic) publishing catastrophe in the history of comics — maybe in the history of the print medium.

I had only met Eastman once before years ago and spoken to him on the phone once or twice. Eastman had in fact canceled a Journal interview he’d agreed to during the period he “sold” Tundra to Kitchen in 1993; his cancellation was probably a bunker reaction to the Journal’s dogged attempt to ferret out the truth behind Kitchen Sink Press’ disingenuous press releases about the transaction, which, Eastman reveals here for the first time, clearly misrepresented it in both spirit and letter (in fact, Eastman bought a majority interest in KSP and in effect sold himself his own company). But, a year ago, Eastman called me and said he was ready to talk. My impression of Eastman, based on a very long day I spent with him at his Bel Air home in October, 1997, is that he is fundamentally decent and well-intentioned, but his combination of wide-eyed naivete, canniness, and good intentions was unanchored by any concrete philosophical, aesthetic, or intellectual disposition. He wanted to do good but hadn’t a clue as to how to do it, and only the vaguest conception of what “good” meant in the context of a publishing company.

There was certainly too much money at Tundra and too little of everything else. About money, the renowned economic philosopher Wyndham Lewis wrote, “Money spoils many things for it seems to most people who possess it so much more important than their poor humble selves, that they cannot believe, or trust their judgment to believe, that it does not overshadow them; and when their personality is called upon to compete with it (as is I suppose always the case with a wealthy person) they feel that it will master them forever.” Money was certainly more important than Eastman’s poor humble self, a reversal of priorities that proved disastrous. Tundra was both a managerial and a conceptual mess, but the managerial lunacy shouldn’t overshadow the fact that the company was editorially rudderless.

In the absence of a guiding editorial vision (or even coherent taste) Eastman glommed onto Creators’ Rights as the conceptual glue that held Tundra together. The problem was, neither infinite amounts of money nor a devotion to creator rights could manufacture talent out of thin air and as a result, Tundra’s output was all over the map. Such a variable editorial line-up would have put even a crack marketing team to the test, but to Tundra’s relatively untrained staff, it proved hopeless. To this, you can add other detrimental side effects, for instance, books that could’ve sold well and been profitable to other publishers (not to mention the creators), were sucked into the Tundra black hole and practically lost. Then, there was the rampant irresponsibility of creators who took huge advances and never turned in the work for which they were paid. Steve Bissette, a close observer and participant at Tundra, lamented that Eastman never learned anything from the fiasco of Tundra [in issue #185], but what lesson could Eastman or anyone else divine from this painful, tragical, and pixilated episode? Surely Eastman is not about to try anything like this again, and no one in his right mind who has the kind of money Eastman had at his disposal would repeat Eastman’s mistakes. The sad disaster of Tundra was uniquely Eastman’s own.

I had been warned by more than one person that Eastman was as slippery as an eel and that it would be difficult to get a straight answer out of him regarding Tundra; on the contrary, he appeared to be embarrassingly forthright and largely free of guile about his responsibility in the self-immolation of his own company. If you didn’t think it was possible to lose $14 million publishing alternative comics, read on.

— Gary Groth

THE LAST BOY IN MAINE

GARY GROTH: Could you tell me where you grew up, what your upbringing was like?

KEVIN EASTMAN: I grew up in Maine: in the country outside of Portland, in southern Maine. I attribute a lot of my creativity or imagination or whatever to that time period because there was really not much to do there. I had a paper route. There was a local drug store that sold comic books; that’s where I discovered things like Gene Colan’s Daredevil and Jack Kirby’s Kamandi, back when they were all still 20 cents apiece. And I used to draw. Constantly. From the time I first saw a comic book, that’s all I ever wanted to do as a career ... tell stories.

GROTH: This was a rural environment?

EASTMAN: Very rural. The most exciting thing to do in the neighborhood was hang around the store and gas station — which just happened to be the same place. We used to ride motorcycles or hang out in sand pits: lots of fields; trails through the woods. Build forts.

GROTH: [Laughs.] Hang out in sand pits.

EASTMAN: Hang out in sand pits. You ever do that?

GROTH: [Laughs.] No, I have to say I never have.

EASTMAN: That was a big thing for me. [Laughter.] It was wicked fun, all things considered; we hung out in sand pits probably until high school, because once you graduate from throwing rocks off the top of sand pits, riding motorcycles in sand pits, and discover drinking, then you hung out and drank in sand pits.

GROTH: Sand pits are versatile [laughter] places.

EASTMAN: Such was life growing up in Groville, ME.

GROTH: May I ask what your parents did?

EASTMAN: Well, my parents were separated. They separated when I was about 9, but my father was a tool and die maker and he used to draw a lot. I still have an old folder of cartoons of cars. My grandmother was a painter, so I think my talent is definitely inherited. Or ... what I call my talent anyway ... is inherited from them. My mother worked as a phlebotomist. She was a nurse in a hospital where she would draw blood from patients. So we called her the vampire. But they separated when I was 9.

GROTH: Was that difficult for you?

EASTMAN: Yeah, it was kind of weird. I remember coming from school one day and Dad’s packing. And he’s like “I’m going to live at Grammie’s for a while.” Shortly thereafter he moved out of state. For about four or five years, he was completely gone. My mother met a man that she’s been with ever since. Twenty-seven or 28 years they’ve been together. He used to pave driveways ... a real intellectual [laughs] just kidding: a goodhearted person.

I remember Dad calling; he’d call for Christmas and birthdays. It was kind of a weird thing. I really didn’t care for him that much then. When he finally decided to come back to the northeast and be with his kids, it was no big deal. I really didn’t like him that much for a long time. He used to take us, every Sunday, to do stuff, my sisters and I. Actually, he used to take me to life drawing classes, because I really loved to draw. That was kind of great. Introduced me to people like Heinrich Kley, N.C. Wyeth, and all these old-time artists, you know, books he’d seen when he was a kid growing up.

GROTH: Were you close to him before?

EASTMAN: Can’t recall. It was one of those things that fades away, I guess; what do you remember of your childhood? I remember stupid things: eating Twinkies at the store; the paper route; buying comics; drawing. I don’t really remember much more.

GROTH: It almost sounds like he left just at that stage in childhood when you would have become close to him.

EASTMAN: Exactly, when a boy needs a father figure. These days, all is forgiven, and we have a great relationship, but it was really rough for a while.

GROTH: So your stepfather took over that position?

EASTMAN: No, he couldn’t. My mother, she was the top dog: she ran the family, she ran the house, she ran Larry’s ass off ... she was the queen and she was very strict. On the one hand, she was supportive, but in a most interesting way. I remember ... it is kinda funny now, and still seems very clear today, one of the most inspiring things she said to me, when I was maybe 12 or 13, again drawing all the fucking time — in my room, comic books, everywhere ... she came up and she’d say, “Jesus, you better be good at that, because you’re not good at anything else.” [Laughter.]

She’s very much of the tough-love scenario. But she was supportive, and my dad was, in his own way. When I graduated high school I wanted to become an artist, a comic-book artist. Which was silly to everybody on the planet. My high school art teacher was very supportive but not — like, you really got to do something with your comic art. More like fine art. Even when I applied to colleges, like Portland School of Art, or Rhode Island School of Design, and these places were just insulted that my portfolio contained anything comic book-like, that wasn’t art to them! My father said he would help pay for college ... as long as I didn’t go to art school. He said, “I know you love to draw, but it’s not practical!” He was very old-fashioned. He was like: “Get a job ... a real job.”

GROTH: He didn’t think you could earn a living doing that.

EASTMAN: He was absolutely positive you couldn’t. His idea was, you get a job where you can support a family, so you can take care of your family. Then if you want to draw on the side as a hobby, you can do that.

At that age, when you’re getting out of high school, you’re pretty much, “Fuck you, I’m doing anything I want.” So I went to art school for six months. [Laughs.] They didn’t care for me there, either. [Laughter.]

I went to the Portland School of Art, because it was semi-affordable, and local. They had artists that graduated that could paint their asses off, yet working in 7-11s to pay back their fucking student loans and starving. You know what I mean? They were very much against what I wanted to do ... it was insulting that I would draw anything comic book-like. Or refer to that as an art form. And that was very weird to me. So I made up my mind, at that time, that I still knew that that’s exactly what I wanted to do. I figured that I will take from them what they can give me and apply it to what I wanted to do with it. A lot of it helped: life drawing, of course, and object drawing ...

GROTH: Can you skip back and tell me a little about your interest in comics? Were you just maniacally interested in comics, did you buy a lot of comics ... ?

EASTMAN: Well, there were only one or two other kids in the neighborhood that really liked comics. Most of them didn’t care or probably couldn’t read that well. Well, I couldn’t read that well either. I still can’t spell that well, but that’s another story — yeah, I loved ’em and as much as I could afford with my paper route money, I would buy comics. I liked weird shit. Well, what I called weird shit. Some kids liked Superman or Batman, and things like that. The closest superhero comic I liked and bought regularly was Daredevil. I liked Weird War. I liked Sgt. Rock. I liked The Losers, a lot of war comics. Not much superhero stuff.

GROTH: Did you escape into comics?

EASTMAN: Oh, definitely, big time.

GROTH: Do you think your fractured family life had something to do with your intense interest in, or escape into, comics?

EASTMAN: Yeah, I’m sure it did ... my room was a pretty safe place. I had all my comics there and all my stuff to draw on. You could sort of hide there for days if you needed to.

GROTH: You once said, “I remember reading my first Jack Kirby comic when I was very young, and deciding that was what I wanted to do.”

EASTMAN: Mm, that’s right.

GROTH: Kirby had a big effect on you?

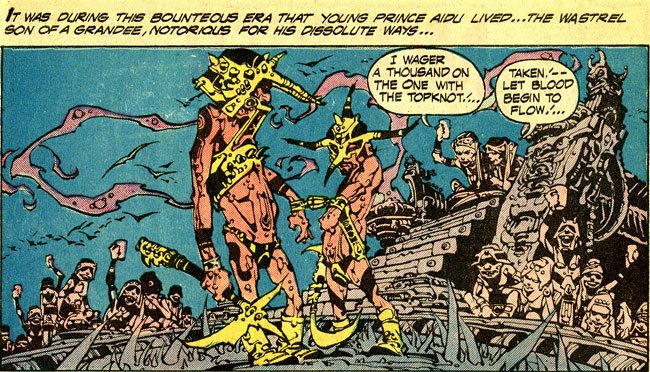

EASTMAN: Huge. The biggest. I think that looking at Jack Kirby’s work made me obsessive. I’ll dig out, just for fun, if you want to show some of the stuff in the interview, all my early drawings were totally Kirby-inspired. His stuff was kind of manic. It was kind of abstract. It was really powerful. Simplistic, I guess? The stories were really never that complex. But very linear, simple, and I just thought exciting. Kamandi was my favorite. “The last boy on earth.” I was like, “I wanna be the last boy on earth.” Whatever.

But yeah, he was brilliant to me; I used to just pore over his stuff. I still have those comics that I bought from that time period today and they’re just beat to fuck, barely held together. He was a huge influence.

GROTH: So you went to art school immediately after high school? What art school was that?

EASTMAN: It was the Portland School of Art. In Maine, there’s not a lot of work opportunities, so I would cook lobsters during the summers in a restaurant, and basically, grew up in a kind of atmosphere where you work all summer long, from Memorial Day to Labor Day, because that’s when all the tourists are there, and you save all your money to get you through the winter. For four or five years, I still did that even after the first issue of the Turtles, I was still going back to Maine for the summers to cook lobsters. [Laughs.]

SCHOOL DAYS

GROTH: You went to art school for about a year?

EASTMAN: It was six months, actually.

GROTH: And they tried to indoctrinate you into fine art, or they tried to move you into a direction away from comics?

EASTMAN: Yes. They preferred I paint things like this; they would tear up colored pieces of paper, put them inside of a box, and tell me to do a painting of that using a palette knife. I’d paint that, or other weird shit. I used to do stuff in design classes where you have this 12-inch by 12-inch gray scale, and these one-inch squares of gray and you’re supposed to arrange them in a pleasing, “most” interesting manner. I used to hang out with this kid, Peter Goodman, who also liked comics, and so, we’d bring in gray scales to a Tuesday lesson, and the teacher would critique them: “No, no, you’re close, you’ve almost got it, I think you really need to give it more thought ... ” and whatever. We’d never work on the fucking things, we’d bring them back the next class, and you’d just say to the teacher, “Well, I really thought it through and I did this, then I added more warms here, and I think the blacks really brought the whole thing together this way.” And she’d be like, “Yes, yes, I see it. You’ve really got it this time.” So to me it was kind of fucked up. [Laughs.]

GROTH: It was bullshit.

EASTMAN: Kind of bullshit. I got enough grants and student loans to go for a semester. I applied for grants for a second semester, but my mom and Larry were at the income level where you were poor enough to get some help, but were just making enough money that you couldn’t get more government assistance. I was just making too little to pay for myself. So I couldn’t attend second semester. I opted to just take night classes occasionally and work.

GROTH: Did they teach you figure drawing?

EASTMAN: Yes. And that was the one thing I stuck with even after school. I had figure drawing classes, and what they call a 2-D drawing class, which is object drawing. Drawing bags and couches and tires and things like that. The figure drawing is something I always went back to whenever I could fit a class in.

GROTH: So you were taking classes, but you also must have been working as well. What were you doing?

EASTMAN: Working in restaurants. I had this great philosophy that was taught to me in the first restaurant I worked in, in high school. As a freshman I used to work at this variety store that had a little restaurant in the back, in Westbrook. The owner said, “You know, kid, if you work in a restaurant, and I don’t want to catch you doing this here, by the time you get your own apartment, you can eat all your meals at the restaurant, while you’re working. On your payday, your day off, you come in to get your paycheck, and then, grab a snack while you’re there. That way it leaves you more money to spend on beer, chicks, and your apartment, because you’re eating all your food there.” And I’m like, “Oh, I can relate ... ”

GROTH: Words of wisdom. [Laughter.]

EASTMAN: Words of wisdom from Louie Audet of Westbrook, ME.

MAKING COMICS

GROTH: When did you actually start drawing your own comics?

EASTMAN: In sixth, seventh grade. Me and a friend of mine, Jim McNorton, who was the writer, as he couldn’t draw — neither of us could do either at that age, but we tried really hard — he would write all these really outrageous scenarios, and I would draw them. Then ... remember the old mimeograph printers? You had like these two pieces of carbon paper and you could draw on one side of them these one-page comic strips, print them in the school office, and try to sell them around school. Didn’t sell that many, but that was my first experience with publishing. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Presaged Tundra.

EASTMAN: Same thing: we got extra credit, but they just didn’t sell.

GROTH: Just a loss on a lesser scale. [Laughter.]

EASTMAN: Yes, for sure.

GROTH: Now correct me if I’m wrong, you published the first Ninja Turtles comic in ’84. You would have been about 23-24.

EASTMAN: 21-22. I’m 35 now.

GROTH: It sounds like you didn’t have much support from parents or teachers or anyone else for your interest in becoming a comics artist.

EASTMAN: Not really, but one of my biggest inspirations after Jack Kirby, and definitely the experience in publishing that led me to the whole world of self-publishing was a gentleman by the name of Clay Geerdes. Did you know Clay?

GROTH: Yeah, yeah. I knew him. We corresponded.

EASTMAN: He passed away last year, which was heartbreaking for a number of reasons: one, because he passed away; two, because I really lost touch with him over the years and it makes me sad. I grew up reading comics and wanting to draw comics. I discovered Heavy Metal in 1977, when I was still in high school; I graduated in 1980. Heavy Metal led me to look for people like [Richard] Corben, which led to undergrounds by Kitchen Sink, Last Gasp and Rip-Off Press. When I used to work cooking lobsters, this friend of mine, we used to drive to the Million Year Picnic down in Boston and scour the racks for all these old underground comics. So by the time I thought I was good enough to start submitting my work, I submitted all my early stuff to publishers like them. Denis Kitchen was the only one that wrote back a note saying, “You still have a long way to go. Keep trying, you’ve got something there, but you should try Clay Geerdes or Brad Foster ... these guys do minicomics. They may point you, help you along and whatever.” So then I wrote to Clay, and Clay ended up being my first publisher.

GROTH: He published some minicomics for you?

EASTMAN: Yeah. There were just these little 8 ½” by 11”, photocopied pieces, folded twice into minicomics, but he also did a little bit slicker ones, photocopied also, folded in half, with a slightly heavier cover. I did a series of probably 50-60 drawings for him. Different covers ... they’d all have the Clay Geerdes Comix Wave logo worked into them, and all these different artists would do renditions of his logo. Then he used to send me newspaper clippings, of bizarre little anecdotes from the newspaper like “Man Gets Ticketed 113 Times, Even Though He Was Dead And Slumped Over The Wheel Of His Car.” I’d illustrate that, and he’d put it in one of his minicomics. I remember to this day getting my first check for $7, for a published drawing on the cover on one of his comics. That was my first paid published work, and it really flipped me out.

ENTER PETER LAIRD

GROTH: When did you hook up with Peter Laird, how did you meet him, and how did you guys form a partnership?

EASTMAN: While I was cooking lobsters I met a waitress who was also going to school at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, near Northampton. So once Labor Day ended, there’s not much work left in Maine, and I couldn’t afford school, so I followed her down to Massachusetts. There I found a local free newspaper called Scat. It was very similar to Clay Geerdes’ type of stuff, only newsprint, a little bit bigger, 8 ½” by 11”. They had these local artists do these underground-like comic strips, and their offices were in Northampton. So I got on the bus, went over to Northampton with my portfolio of stuff, and tried to sell work to them. Around this time, they figured out that this magazine was supported by local businesses advertising ... and that they were starting to make more money designing ads for these businesses than doing comics! So they said, “We’re not really doing Scat anymore, but hey, you should meet this guy Peter Laird. He draws the same kind of weird shit you draw: Kirby-inspired whatever, babes and guns and fucked-up creatures, that kind of stuff.”

And they gave me his address. He lived in downtown Northampton. So I wrote him a note. He said, “Yeah, come on by. Let’s get together and show off our portfolios.” I remember going into his apartment, his tiny studio apartment that had 50,000 comics in it, toys, shit, and junk, but the first thing I saw when I walked in was this unpublished pencil page from The Losers that Jack Kirby had done. That was the first original Kirby I’d ever seen and I just about wet myself, as you can imagine. He was equally a huge fan of Jack Kirby, and we just hit it off Big Time. That day we said we should really try to work together, we should each go home tonight and pencil something that we’d trade off the next day and ink each other’s work. We published those first two stories that we did in a book called Gobbledy-Gook much later at Mirage, back in the black-and-white days when you could sell a whole lot of black-and-white comics.

GROTH: When would that have been?

EASTMAN: That was 1981, when I met Pete. I moved back to Maine that following summer to cook lobsters again, and he ended up meeting the lady who is now his wife, Jeannine. She got a job teaching at the University of New Hampshire. So they moved from Northampton to Dover, N.H. I was working in Ogunquit, which is 20 minutes from UNH. That was 1983. So when I finished work that summer, Pete said, “Come on. Move in. We’ll form a little studio, and try and sell our work together.” At that time, we weren’t thinking self-publishing; we were going to sell things to Marvel or DC. Pacific Comics was just starting up, Capital Comics the same, and there were a few other people publishing, so we thought we had lots of options.

GROTH: And what was Peter doing at this time?

EASTMAN: He was supporting himself through his illustration. He was doing gardening drawings for the Daily Hampshire Gazette, the newspaper back in Northampton: a few greeting cards; a few TSR, Dungeons & Dragons spot illustrations. It was very tight, he was barely getting by, but he was making a living.

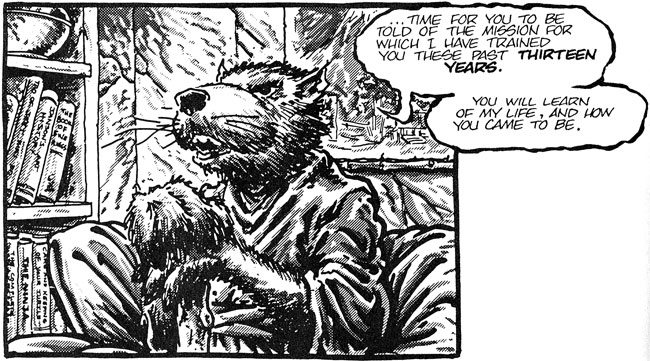

I worked in a restaurant, and we drew every night. I’d get off work and we’d hang out and draw. It was in the fall of 1983 that we formed Mirage Studios, and, as the story goes, it was a mirage because it wasn’t a studio, it was our living room. We’d sit there, and Pete’s favorite shows were The A-Team, TJ Hooker, Love Connection, really bad TV shows, but he liked them. My goal in life was to annoy him as much as possible while he’s watching his shows. We’d done some work on a robot concept, sort of a misunderstood rogue robot story, as he was a big Russ Manning fan also — called The Fugitoid. While we were working on that one night, I did a drawing to make Pete laugh, of a turtle standing upright. He had a mask on. He had nunchucks strapped to his arms, and I put this Ninja Turtle logo on the top and flung it over to his desk. He laughed, thought it was funny, and did a drawing to top my drawing, changed some things, fixed some things, and then I had to top his drawing. So, I did four of them all standing together with different weapons, and when he inked it, he added “Teenage Mutant” to the “Ninja Turtle” part, and we had this one drawing. Literally the next day we get up and we said ... at the time we didn’t have any distracting paying work going on ... “Let’s write a story to tell how they got to be the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” So we did.

I worked in a restaurant, and we drew every night. I’d get off work and we’d hang out and draw. It was in the fall of 1983 that we formed Mirage Studios, and, as the story goes, it was a mirage because it wasn’t a studio, it was our living room. We’d sit there, and Pete’s favorite shows were The A-Team, TJ Hooker, Love Connection, really bad TV shows, but he liked them. My goal in life was to annoy him as much as possible while he’s watching his shows. We’d done some work on a robot concept, sort of a misunderstood rogue robot story, as he was a big Russ Manning fan also — called The Fugitoid. While we were working on that one night, I did a drawing to make Pete laugh, of a turtle standing upright. He had a mask on. He had nunchucks strapped to his arms, and I put this Ninja Turtle logo on the top and flung it over to his desk. He laughed, thought it was funny, and did a drawing to top my drawing, changed some things, fixed some things, and then I had to top his drawing. So, I did four of them all standing together with different weapons, and when he inked it, he added “Teenage Mutant” to the “Ninja Turtle” part, and we had this one drawing. Literally the next day we get up and we said ... at the time we didn’t have any distracting paying work going on ... “Let’s write a story to tell how they got to be the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” So we did.

We started working on that. And around February or March we’d finished 40 pages of a fleshed-out story, trying to justify why they got to be these mutant turtles. We borrowed some bits from Daredevil’s origin, and we created the rest. I was getting an income tax return back for five hundred dollars. Pete had two hundred dollars that he cleaned out of his bank account, and my uncle, who used to sell us art supplies during that period, loaned us a thousand dollars to print 3,000 copies on newsprint, with a two-color cover of the first Turtles book. We didn’t know anything then. We said, “OK, we’ve got 3,000 comic books in our living room.” Some were used as a coffee table, some were used to put a lamp on in the corner, and we had enough money left over to put an ad in the Comics Buyer’s Guide, to sell them at $1.50 plus postage. We sold a few, but from that ad distributors started calling and said that they’d like to carry our book. I guess they’d had some comic stores that called about it. So we’re like, “OK, we’ll call you back.” We said, “Well, what do we do?” “How about if we try this; I think they usually give a discount so, tell them we’ll give them 10 percent off cover, and they have to pay up front, and so on and so on ... ” So we called them back, and when the guy got done laughing, he said, “Well, this is how we do it, kids.” And explained to us how they work. Within a couple weeks we had sold out of the first 3,000 copies, and before paying my Uncle Quentin back, we still had orders coming in, so we printed another 6,000, and those sold.

This was in May of 1984. Then I had to go back to work cooking lobsters for the summer. So we took a little hiatus.

GROTH: So the first issue made a profit, then?

EASTMAN: The first issue made some money, yes.

GROTH: You sold 9,000.

EASTMAN: After paying my uncle back and all the other bills, it was maybe a hundred bucks, two hundred dollars profit-wise we split. Maybe a little more.

GROTH: Did you see the possibility of earning a living from doing this?

EASTMAN: Not at that time, but to us, it was just amazing. We had our own comic! My parents were like, “Yeah, yeah. That’s really nice.” Then you give copies to your friends and other people and it’s like “Yeah, well, great. Congratulations.” It wasn’t until that fall when Pete ended up moving to Connecticut with his wife, who got a teaching job there, and I moved back to Portland, ME that we started working on the second issue. That is when we realized the possibilities. I made a couple trips down to Connecticut to visit and work. A long bus ride. You used to live in that area, didn’t you?

GROTH: I lived in Stamford.

EASTMAN: Stamford. He was up in Sharon, the Torrington area. So, I made a couple trips down, and we finished issue #2, then solicited for it through the direct market, and we got orders for 15,000 copies. I remember I was in my apartment in Portland, and Pete called, flipping out. He was like, “Do you realize that we’ll make about two thousand dollars each on a 15,000 press run, after everything’s paid, and if we did six of these a year, we could get by just doing comics?” About three days after that conversation, I packed and I moved to Connecticut, and we started. I found a little apartment there. We lived in Connecticut for, let’s see — that would have been ’84 and ’85. I think we did three or four issues that year, and it went from 15,000 copies for the first printing of #2 to a re-solicitation of #1 that sold almost 30,000 copies to a re-solicitation of #2 which was higher than that, to the first solicitation of #3 which was 50-55,000 — it was making incredible jumps like that, and by the end of ’85 into early ’86, we were filthy stinking rich. In our own minds. We were paying our rent, we were putting money in the bank. We were still doing everything ourselves, doing the whole thing, and the dream had come true.

THE GOOD OLD DAYS

GROTH: Let me skip back. How did you guys collaborate? How did it break down?

EASTMAN: What we did was unusual. I guess Pete was more of an illustrator, very finely detailed, amazing stuff. And I was more into telling stories, he hadn’t done that much of it. So what we would do was sit down and basically flesh out the issue. We’d talk it through, I’d make notes longhand. We’d figure out where it starts, a basic beginning, middle and end, and some detail, and then I would do the breakdowns and the layouts for the entire issue. Some were as simple as a lot of gestures and flow on legal pads for each page, to some more detailed drawings.

So, we would work in this manner, talk out the stories, I would do all the breakdowns, then Pete and I would go through them together, and he’d say, “We should change this, this doesn’t work, we should try to improve this,” or whatever. We’d clean those up, and then Pete would go through and do the final script based on whatever crazy notations I made. Besides, he was a much better speller. [Groth laughs.] And, a better writer ... probably still is. Then we’d each take half the stack and start penciling. All the early pages were very small because we did them on duo-shade, you know, that graphic tint paper? It was $22 a sheet for a 17" by 22" sheet, and especially in the early days, we could get three pages if we made them small. So, we’d each start penciling, swapping back and forth. The idea was to try and get half of each of us on each page. Once it was all penciled, I would letter it all and then we’d again divide up the stack and it would be a race to inking. We’d both go through the pages, again trying to get half of our styles on each page. It was always this manic process as there were these really cool panels and then there were the boner panels — you know, the “nothing going on” panels. And so I’d rush through and try to do the cool poses, and Pete would do the same thing. We kept swapping them back and forth, until the fateful last few weeks when we had to go in and draw scenery and backgrounds. Then we’d duo-shade together. Sitting in the same studio, literally passing the pages back and forth.

GROTH: A very organic collaboration.

EASTMAN: Exactly; the Good Old Days.

GROTH: Is the Ninja Turtles owned 50/50?

EASTMAN: Yes. It’s always been that way. Since the beginning, we had always known that without the other person, it never would have evolved.

GROTH: So you publish the first issue in ’84, and it took off almost immediately. The second issue came out how long after the first?

EASTMAN: January of ’85. So it was a while.

GROTH: Seven or eight months afterward. Then it really took off after you did #2. And you realized you had something.

EASTMAN: Yeah, we realized we had something then, and we were sort of figuring it out as we went along. We didn’t know how long it was going to last, but at that young age, you sort of go for it.

GROTH: How long did the sales keep climbing?

EASTMAN: The sales actually peaked a year later. The biggest-selling Turtles issue was Turtles #8, which was the Cerebus/ Turtles crossover. It was a story I wrote. Pete had very little to do with that one. He was working on something else at the time. I did all the layouts and the pencils, and then Dave Sim went in and inked Cerebus throughout.

GROTH: And what did that sell?

EASTMAN: 135,000 copies.

GROTH: [Laughs.] Image would love that today.

EASTMAN: [Laughs.] Yeah, a lot of people would.

GROTH: DC would love that, too.

EASTMAN: I think around that time we ended up moving back to Northampton. We really felt that we were making good money, around seven, eight, nine ... ten thousand dollars an issue each, black and white, still newsprint with color covers. Actually #5 was the first full-color cover. We could afford to live wherever we wanted to.

GROTH: And you actually chose to live in Northampton?

EASTMAN: We chose Northampton. Pete grew up in North Adams, which is pretty close to Northampton, and he’d been to school for four years for printmaking in that area. He had a lot of friends there. I really had no attachments and thought it was cool because that was where we met. The short time I had lived in Amherst in ’81 and ’82, I used to hang out in Northampton — Amherst was really boring — but Northampton was a hip, kind of cool, kind of grungy, little mini-city. But very small. It’s changed somewhat today. It’s more like Disneyland, Main Street U.S.A.

GROTH: I heard it’s the lesbian capital of the country. Is that true?

EASTMAN: If it’s not the capital, it’s definitely got an inordinate amount of lesbians in it. I think Smith College, which is one of the original seven sister colleges, you know, Wellesley, and all those others. Smith is right in downtown Northampton. Actually, there are seven or eight colleges in a nine-mile radius. UMass is there, Amherst College, Mt. Holyoke, Hampshire College, and there’s a very young population. Anyway, there’s some statistic that I read, and whether it’s correct or not I don’t know, but it said 30 percent of the women that go to Smith end up either coming out a lesbian or have had a number of experiences but, yes, it’s very much a part of downtown. There are a lot of kids, obviously, with all of the schools, there’s a lot of tourist traffic. With Smith College being downtown, and whereas it’s a very expensive school, there are some nice restaurants to lure the rich parents that come to make sure their daughters aren’t becoming lesbians. [Groth laughs.] When I was 18 or 19 living there, it was very different. Very grungy. I used to be able to get served in bars downtown. There were some pretty dumpy little bars right off Main Street, which are parks and gardens or more upscale restaurants now.

“LET’S DO LUNCH”

GROTH: So when did you move back to Northampton?

EASTMAN: In the first part of 1986, I believe.

GROTH: Now in 1986 you signed with licensing agent Mark Freedman. Can you tell me how the Turtles fortune was built and how you decided — how did you know to sign with a licensing agent?

EASTMAN: In late ’85, with the now more widely known success of the Turtles, we started doing a little bit of licensing. We did a role-playing game with Palladium Books, Kevin Sembieda; we did a couple T-shirt things, these were people that just called us and said, “We want to do glow in the dark Turtles T-shirts,” so we did a deal. We also did a deal with Solson comics. Remember Solson? Rich Buckler and Sol [Brodsky]’s son?

GROTH: Yeah, my God.

EASTMAN: Yeah. We licensed the Turtles training manual to them and got ripped off.

GROTH: You were one among many.

EASTMAN: Unfortunately one of many. [Groth laughs.] We had been approached by a couple of different agents that were like, “We can make toys and movies if you sign with us for five years exclusive; we’ll make you millionaires.” For us, one: we were making good money, and two: we had learned a few things. We all remember Siegel and Shuster, and around that time, there was a big fight to get Jack Kirby’s artwork back, which I think you were pointing to a lot of. A lot of the industry people like Frank Miller were doing a lot of speeches regarding creative rights, and creative ownership, which was kind of interesting and weird to us at the same time. We were aware of it, we knew Steve Bissette and what he’d been through and all the evil stuff that had been happening to other people who were trying to retain and own their rights. We started going to conventions around this time, meeting folks like Dave Sim, Mike Kaluta, and many others, all of which had corporate horror stories. We were aware enough to file copyrights and trademarks. Well, we had copyrights just by publishing it, but we filed trademarks to protect ourselves.

But we never experienced their side of it. We always had complete say and complete control over the whole thing. So when agents came along, we were like, “No. We’re happy. We’re making money; we’re doing what we want. Besides, you feel really slimy to us.”

And I know that sounds silly, but you know how you get weird vibes from a person.

GROTH: Were they real hustlers?

EASTMAN: Yeah, these guys ... New York/L.A. types. “Come on. Let’s do lunch.” Mark Freedman actually approached us in the same manner. It was in ’86, he had heard about us through this person and that person and whatever. So, he called us up and said, “I want to come talk to you about licensing.” And we were like, “Yeah, yeah, sure. Fine. All right, come on up.” He was in New York. To give you an idea of how important this was to us: We had finally moved out of our living rooms, and gotten a little space. We were literally painting it that day. It was two rooms. So Mark shows up and we’ve got paint all over us. We’re in shorts as it’s in July. He does one of these — we open the door, he takes one step and freezes solid. He’s got his thousand dollar suit on, his leather briefcase, the perfect hair, the whole thing and looks, and says, “Eastman and Laird?!” And we’re like, “Yeah, come on in.”

He went through his spiel. “I can make you millions, blah, blah, blah ... five year contract ... blah, blah, blah.” We said, “Look. Tell you what. If you really think you can do something with our Turtles, we’ll give you 30 days.” And we literally signed it on a napkin: 30 days non-exclusive to see if you can get any nibbles, and if it works out, we’ll go from there. In 30 days, he had letters of interest and commitment from Playmates Toys. We said, “All right.” He said, “Look, I want to take you to California, we’ll go to Playmates, and hear what they have in mind.” So the toy company paid our way. It was our first trip to California, which was pretty funny in itself.

GROTH: Why was that funny?

EASTMAN: It’s just that [laughs] I’m sure we looked like a couple of fucking country bumpkins, you know? [Groth laughs]: which we were. Sitting in this corporate office with all these weasels in suits. But they got it. They got the Turtles, I guess. They liked the moralistic side of them, which I don’t think Pete and I really ever saw in the Turtles in those days. We just tried to make them do the right thing, and we created this little mythology of honor within the Ninjitsu, which there isn’t any. [Laughs.] Ninjas were ruthless mercenaries. [Groth laughs.] They worked for anybody that paid them to kill or assassinate or do whatever dirty deed.

But, they liked the characters and wanted to develop them to see if they could work as toys and cartoon shows. Playmates had had some successes, and this was their first venture into boy’s action figures. One of the reasons why Mark selected them, as he told us, was because companies like Mattel and Hasbro would regularly buy concepts and “sorta” develop them, while intending to bury them for a year or two so they wouldn’t compete with other things they had on the shelf. But Playmates believed that the Turtles could be really huge, and they were willing to invest millions of dollars into making toys, and millions of dollars into making an animated five-part TV show. So, we eventually signed with them, and signed with Mark for a three-year contract.

GROTH: Now let me skip back just for a second. Am I correct in assuming you were influenced by Miller’s Ronin comic?

EASTMAN: We pretty much blatantly ripped off the cover and its style, the jagged balloons, the Miller style. The roughness of the drawing, I probably pushed that on Pete. Pete ... he’s eight years my senior, and he already had a very distinctive style: very linear and highly detailed. I was without a doubt an absolutely huge Frank Miller fan and I don’t think Frank’s ever forgiven me for that. I mentioned when I was a kid I used to read Daredevil when Gene Colan used to do it, and Bob Brown did it for a while, and you had a bunch of other in-house staffers do it, and then Miller came on the scene, I think Roger McKenzie was writing it ... it was like #158, and I thought it was just brilliant. Miller always experiments and tries different things and really is one of those people that moves the comics industry along, pushes the limits, and creates new heights that it should rise to, with Ronin, and Dark Knight, and even Sin City. But the coolest thing even today when I look back at the growth period of Frank Miller between #158 and #191 or #192, his last issue on Daredevil, it’s pretty phenomenal. He was, I think, very Kirby-esque in that he had a very dynamic style of storytelling. I was very inspired. Ronin ... Pete hates [laughs] ... Pete’s never really liked Ronin that much, but I just loved it. I really flipped out over what Frank was doing.

TONING DOWN

GROTH: According to an article in something called Continental Profiles, July 1989, written by Frank Loveche, it said, “All agreed to soften the Turtles for mass consumption. And so Playmates underwrote a five-part cartoon mini-series that turned the Renaissance Reptiles into pizza-snarfing party guys.” [Eastman laughs.]

Is that accurate?

EASTMAN: Yeah, that was the one from the airplane. Continental Profiles: an interview from the peak years.

GROTH: That sounds right.

EASTMAN: [Laughs.] I’m laughing because I remember more people saw that than anything else we did! It was one of those in-flight magazines, and we had all these people saying, “Oh, you’re really in the big time now, because we saw you in the in-flight magazine.” [Laughs.]

GROTH: A captive audience.

EASTMAN: A captive audience. But yeah, from day one, the first meeting at Playmates they wanted changes, I mean, in the early issues of the Turtles, we had violence but not graphic violence, but there was definitely some hardcore action. We had the Turtles swearing, drinking beer! In issue #3, they go into April’s apartment, and she says, “Do you want something to drink?” And one of the Turtles goes, “Yeah, you got any beer?” [Laughs.] My influence, I know, Peter never really drank.

GROTH: And they all pass out.

EASTMAN: And then they all pass out, end of story. [Laughs.] Playmates said, “Our specific audience is 4- to 8-year-olds, and this is the audience we need to shoot for.” In the origin story there was death, murder and revenge — that was softened considerably. A lot of the violence was toned down, obviously, to fit broadcast standards and practices. When we did the first color cover to Turtles #5, the only way you could tell the Turtles apart was their weapons. They all had red masks; they were all green; they all had yellow chest plates. They said, “What do you think about coming up with a way to differentiate them a little bit more?” Pete came up with both the different color bandannas and the belts with the letters on them. I even think it was suggested at one time that they even be different shades of green, which in the world of toys and animation just was not doable. They can’t get that finely tuned.

But yeah, we worked literally hand in hand with Playmates and Fred Wolf, who was the animator. We had complete say, and complete approval, under our contract with Mark and Playmates. Every licensee from day one to now goes through us. Nothing gets put anywhere without our approval.

GROTH: How did you feel about toning down your creations for mass consumption?

EASTMAN: It probably affected Pete more than it did me. He was really upset about it and even today he’s very much of a purist as far as the Turtles go. I think he has much more of an attachment to the Turtles than I do. I may have had more in the beginning, can’t say as I really do now. It’s like they never stopped!! I never really thought they would go beyond issue #1. I’d come out of Heavy Metal, and Corben stories and underground stuff where every story could be something different and more fucked up than the last one, or more interesting or whatever ... I had a lot of other stuff in my mind that I wanted to do comics-wise. To me it felt like that any day the whole thing could just fall apart, and then “boom!” you’re on to something else.

So there was some difficulty there, again I think more for Pete than me. But, it was something we both agreed to. We’d have long, long talks, and ultimately say, “We can live with this.” You know? All this stuff was done in 1986 and the early part of 1987 while developing the toys and the cartoons, even through that whole period, we never really believed that it was going to happen. So when you get the first TV Guide that actually says, “Ninja Turtles, playing five days through Christmas Vacation of 1987.” It sort of hits you with a hammer. Just like, you know, is this really happening? The show came out, and it became #1, and everybody’s freaking out over it. We started working on more Turtles shows right away, and the production time with toys, it takes a while to gear up and ship, and the toys finally shipped in like June of 1988, and they’re fucking flying off the shelves, and it ends up being this huge hit. Then the TV becomes the #1series in the fall, and the toys go crazy, people are fighting over them like Cabbage Patch dolls. I remember, even though this was going on, it was like: it’s outside yourself? It’s almost like you’re really watching somebody else going through it. You don’t really feel it’s you, but you’re right in the middle of it. So, we walk into the local Toys “R” Us, in Springfield, Massachusetts, and — I swear to God this is true. We’re going down the aisle and there’s this kid pitching a fit, “Ma, I want the Ninja Turtles!” Screaming: “I want one, I want one, I want one!” And the mother’s going, like, “I’m not buying one of those stupid Ninja Turtles.” And we’re like frozen. Like, this was weird! It was very, very, very fucked up.

GROTH: Do you have any second thoughts about it?

EASTMAN: There was definitely an “Oh my God, what have we done?” thing. It just sort of like, ripples through your whole body like when you’re about to meet somebody you really admire, you know that kind of weird feeling, you get hot flashes, and you’re just going like, “Wow, this is really happening. I need a drink!”

GROTH: But there was never really a strongly held contention that you were not going to violate the integrity of the Turtles? It sounds like you pretty much did what had to be done to mass-merchandise them.

EASTMAN: Yeah. Absolutely. The resolution at the end of the day, even when Pete and I both agreed that, well, there’s some stuff we really don’t like, and some stuff that we wish we hadn’t said yes to, stuff that they wanted to do ... But we said, look, you know what? We don’t think this will work anyway, and we’ll always have our black-and-white comics to tell the kind of stories we want to tell. So that was that little bit of space where we said, “OK, we’re still OK, because we still got our comics.” Which ultimately, because of the success of the Turtles, we could no longer do. Kind of a trip ...

GROTH: Is that true?

EASTMAN: Absolutely. When the Turtles hit, that’s when the drawing stopped. We stopped with — we call it issue #15, but in actuality it was 11 regular issues, and then four one-issue micro-series. Because everybody was doing these four-issue miniseries, we did these one-issue micro-series, one on each of the Turtles. Pete and I really couldn’t find enough time — because he was handling part of the business, and I was handling part of the business, and we’d be juggling a lot of things as well as trying to work out a regular schedule of sitting and actually drawing together like we used to, which became impossible, and just drifted away. It was like, now, working on a licensing program, working on scripts for shows, working on the movies, working on all aspects, and [knowing] nothing about this kind of business! The licensing world is a whole planet in itself, the world of cartoons and what can and can’t be done, that’s another completely different planet, with a whole different set of rules. The same with movies, worldwide copyright and trademark programs, working with agents in countries we’d certainly never been to, some we never even heard of, in managing this whole program by the seat of our pants! We asked a lot of questions, and we paid a lot of legal bills, and figured it out as we went along. We tried to create a system out of a lot of things that were beyond us!

TRUCKLOADS OF LAWYERS

GROTH: Now at some point you had to hire lawyers.

EASTMAN: Yeah, by the truckload.

GROTH: You signed with Mark Freedman. Was he Surge?

EASTMAN: Yeah. He was Surge Licensing.

GROTH: So you signed with him. Now, you must have had a lawyer to confer with before you even signed with him.

EASTMAN: Yeah. We actually had two. Pete had an attorney that was working with him and his wife as they were buying a house, a local, small-town Northampton attorney. Interestingly enough his lawyer, Fred Fierst, used to work in New York in the music business, as well as TV, so he had some entertainment experience. He moved to Northampton for the quality of life, to raise his family and things, so we started with him. I went out and found an attorney, by literally looking in the phone book. His name is Michael Weiss. I still utilize Michael today for certain things. He’s down to earth. They consulted with other counsel, and together we sort of figured it out.

GROTH: And as it grew did you acquire more attorneys, more specialized attorneys with greater experience in that area?

EASTMAN: Some; a lot of them were on Mark’s side: the licensing agent. He had two or three key attorneys that he used that did all of his licensing deals, his movie deals, his toy deals, and TV deals. We had a copyright/ trademark attorney in Waterbury, Connecticut, Bill Crutcher, who helped organize and do the whole copyright/ trademark program worldwide. There were a variety of New York attorneys that Fred Fierst and Michael Weiss would consult on certain things that were sort of beyond their expertise. But our lawyers read every contract. Pete and I, in the early days, definitely in the first four or five years or so, were still reading all of these contracts and asking “Why are there 350,000 whereases, and what ifs, and hereins?” And once we started figuring out the contracts, that’s when they started changing them, you know. Gotta keep those billable hours up! [Laughs.]

But at times, especially when the crazies started popping up, the “I created the Turtles,” ones we’d use more, to help with those, and all the other lawsuits. We would have anywhere between 15 or 20 lawsuits going at any particular period of time in those days.

GROTH: Lawsuits ... people were suing you?

EASTMAN: Yeah, seemed like everybody was.

GROTH: For what?

EASTMAN: Anything! Buffalo Bob from the Howdy Doody show filed a five million dollar suit because he said we stole “Cowabunga” from him. He used to say it in the Clarabell the Cow segment, I guess — I’ve never seen a Howdy Doody show, to be honest — but I guess he used to come out and say, “Cowabunga!” Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon used it through all the big beach blanket bingo movies as a surfer term, and I think Bart Simpson — which I hear he also sued Matt Groening for stealing “Cowabunga” ... It was what our lawyers called strike suits, basically they come in and they say, “We have grounds for a case, and we’re suing you for five million dollars, but after a couple months of due diligence and sorting it out, they’d say, “Look, we’ll settle for fifty thousand dollars.”

We had a lot of people saying they created the Turtles. One guy said that God told him about the Turtles, and he didn’t act on it fast enough, and we did, so now he’s suing us. There was a guy, a street person, that Pete actually helped out a bunch of times. In one instance, he created this thing called Presidents in Outer Space that Pete drew for him. He had George Washington in a space suit — that looked like a Turtle to him! So I guess if you put a guy in a space suit, like an Apollo space suit, next to a Turtle, to him there was enough likeness that he said Pete stole the idea of the Turtles from him. He filed a suit that went on for years! Then there was Fred Wolf, the animation company, that we worked with, hired by Playmates, a work-for-hire animation studio, that basically said they created everything about the Turtles that made them such a big phenomenon. So they sued for half the royalties that we’d made in the entire history of the property. That was a big suit: millions and millions of dollars to deal with that. I mean, this guy’s deposition had stuff like “He put the Turtles in the sewer.” We put the Turtles in the sewer in issue #1. He put our character April in a jumpsuit. That was issue #2; it was ludicrous! It was phenomenal. Anybody that wanted to sue you could sue you for whatever grounds, and did!

GROTH: Didn’t you vigorously fight all these suits?

EASTMAN: Yeah. Yeah, we had to. We were told, understood and believed we had to set a “precedent.” In a lot of cases, especially trademark suits, you really need to have a legal presence, and enforce these, to show that you are protecting the property or you’ll lose your rights! There are still a number of what they call “First to File” countries, a lot of Middle Eastern countries are still this way. There was one guy, and I’m not kidding, this guy’s name is Abu Shady. I guess he would look across the ocean to the United States, and if there was a toy concept that was becoming popular, and his being a “First to File” country, he would file trademarks to your creations in his territory! So, when a year or so later, we go in as it starts becoming popular there, to license, and the guy says, “Excuse me, you want to license my characters here? I own the copyrights and trademarks of these!” He knew exactly how much it cost to fight it in court, and he had already figured out a settlement, which was less than legal battle costs. He said, “You want the rights back to your characters in my territory? Pay me x-amount of dollars and you can then license in my territory.” I heard he was doing this to The Simpsons, Warner Brothers, and lots of other companies.

GROTH: You told me a funny anecdote over lunch earlier and I’d like you to repeat it: about licensing the Turtles to Russia.

EASTMAN: Oh, God. I think I was talking about how crazy the Russian program was in comparison to the insanity that we’d already dealt with. We had done a licensing deal there with this sub-licensing agent named Peter Tamm. We said, “Well, we’ve looked into it and there’s no real government system, there’s no way we can protect our copyright and trademark or enforce anything to protect your rights as we normally to do everywhere else.”

He said, “Don’t worry about it.” Because he had this arrangement where he would manufacture all these goods in factories in Turkey, where we had licenses already, so we’d get percentages of royalties from the increase in factory production in Turkey as well as this guy would import all this Turtles merchandise — comics and toys and you name it — drive ’em in big 18-wheelers into these Russian markets, open up the backs, and sell ’em off the trucks. He said that if anybody infringes on his rights as our agent in that territory, I’m going to send some of my guys over there to kick the shit out of ’em. That’s how I’ll protect the copyright/trademark. Period. [Groth laughs.] I found that to be almost as funny as the Abu Shady thing I was telling you about.

GROTH: Did you find that to be a satisfactory answer to your question as to how to protect your trademark?

EASTMAN: [Laughs.] We were like, “Is that really what it’s like there?” And he said, “You know what? To describe” — and I guess we’re talking 1992, ’93, when the Turtles were really hot — and he said to describe the climate in Russia after the wall had comedown and all these changes were going on, he said it’s sort of like a cross between the wild, wild West and Chicago gangland in the ’20s and ’30s. It was really a free-for-all that all these capitalist ideas were coming in and people were just going nuts.

So satisfactory? I don’t know.

GROTH: Did you sign with him?

EASTMAN: [Laughs.] He was interesting, and he made us a little nervous.

GROTH: Did you sign with him?

EASTMAN: Yeah, we signed with him. [Laughter.] We signed with him and he paid us the money. It was pretty decent money. It was a lot of — Christ, you know, are we dealing with Russian Mafia? Who knows? It was kind of scary at the same time.

WILLING VICTIMS

GROTH: At some point, and I don’t know when this was, it seems to me that you got sucked into the Bissettian and Simian orbits.

EASTMAN: Yeah, but we were willing victims.

GROTH: And I know that you attended one or two of the Creators’ Rights summits.

EASTMAN: At least two of them, maybe more. There was one in Springfield and then we drove to Toronto to do another one with Bissette, Zulli, Pete, and Murphy — Steve Murphy — and most of the Mirage guys.

GROTH: Earlier you said that at some point you had known Bissette. Can you tell me how you met Steve?

EASTMAN: I — Oh God, now we’re going back, to where those drug years affect me more. [Laughter.] I believe we met Bissette at a convention or something. There were always lots of little local conventions, like a couple in New Hampshire, some in Boston, and God ... we ran into Steve somewhere and got chatting about this and that and figured out that he and Veitch lived just about an hour north of us in Battleboro. They used to come down to Northampton for the record stores and what not, so we just started hanging out. They’d come down to the studio, have lunch, and chat about art, the business, etc. Steve used to come down more often and, as we got to be friends, he’d come to the studio and draw. For a while, when it was in my living room, I’d have a bunch of artists over when we were jamming on an issue deadline. Once Pete and I had done most everything, we’d have Michael Dooney helping with backgrounds, and Bissette would do some duo-shading, and eventually did stories. We probably met Bissette, Veitch, and Sim around the same time. Sim’s philosophies were ... interesting and bizarre to us in one sense — and the same with Steve’s in another — to be honest, we were very spoiled, we didn’t pay dues. The Turtles were always “ours,” we’d never worked for anyone else. I mean, I did some stuff for Clay Geerdes, but the Turtles was my first comic effort.

GROTH: You hadn’t been fucked over by big corporations.

EASTMAN: We hadn’t been fucked over by big corporations. We were somewhat aware of that going on, we’re talking ’85, ’86, into ’87 whatever, and there were a lot of people self-publishing, we had the black-and-white boom and bust. Which I think there’s some people that still kind of blame us for that in some way. Which is kind of funny. I mean, I see it as once people figured out that a couple of guys out of their living room can publish a comic that can be worth $25 or $30 on the collector’s market, that anybody could do it.

It was the same thing years later when they were selling millions of Image comics and “Death of Superman” — we’re still not over that crash — but on a much smaller scale. When people were doing Radioactive Black-Belt Hamsters and Kung-Fu Kangaroos. There were 21 adjective-adjective-adjective-noun titles at the high point there, ant they were doing a 100,000+ press runs. The shop owners and the collectors were looking for the next Turtles, the next big collector thing. That’s always been a problem in our industry, that people have short memories. You know, all those shops that probably went out of business in the black-and-white boom and bust, never came back to live through the multiple millions of double cover bullshit that we came through years later.

So Dave Sim was self-publishing: and he was intrigued by us, I think, because we were successful, and we self-published. We were selling more comics than him, and I remember that’s the first thing he said when I met him, “I always wanted to meet someone who sells more black-and-white comics than I do.” Which is kind of a weird thing to say but I grew quite fond of Dave. He has very strong opinions, right or wrong, they were his opinions and I respect that. So with Bissette’s extreme difficulties through the Swamp Thing years and Veitch was just starting to go through some really difficult shit — again, I’m not positive of the time period, but I know Swamp Thing #88 was around then, but maybe down the road.

GROTH: Yeah, it was: ’89/’90, something like that.

EASTMAN: ’89/’90, right.

GROTH: After Bissette got fucked over, Veitch had to get fucked over.

EASTMAN: Yeah, yeah. It was sad, heartbreaking. I think Alan Moore was dealing with the Watchmen issues around that time. I think he was just getting ready to jump because DC had been selling all these promotional things, saying they were promotional and even though they were making profits, they weren’t paying him a royalty!

GROTH: It was around then, yeah: much fucking over and much discontentment.

EASTMAN: I think we felt that it was amazing that this could go on and we realized our good fortune. We didn’t go through all that shit. We felt a kinship in that, although we realized that what they had gone through was horrifying, like other people we admired so much, Jack Kirby and many more that had to deal with corporations that were making millions from their creations and they weren’t receiving any of the profits. Or even getting their fucking original art back. We felt that we were in a like crowd; we could be sympathetic — even though we’d never been there. That, and it was always interesting to listen to Scott McCloud and Dave Sim argue at great length!

GROTH: What would they argue about?

EASTMAN: Everything.

GROTH: The weather.

EASTMAN: The weather, what they’re gonna order for lunch ... no, I’m kidding. Scott, as you probably know — and I have a lot of respect for Scott as well, for many different reasons — but he’s equally opinionated: he’s very, very set in his ideas. I couldn’t name a specific. But Dave would have an opinion “A.” Scott would have opinion “Z” and they would never meet. But they would argue ... and their arguments were epic U.N.-style debate quality. But relating to points in comics. [Laughs.]

GROTH: And that would go on at these summits.

EASTMAN: Yeah. What we were trying to accomplish, or my understanding of what we intended to create out of the Creators’ Bill of Rights, was a manifest of rights we felt creators should be aware that they have! We learned from going to all these different conventions and meeting so many people within the business that already had great difficulties, but had become more experienced in how not to get fucked over, to be careful, what to look for, but there was a whole new crowd of people, younger people like us coming through that didn’t have a clue! Wanting to live that dream as well. Creators that really would do anything to ink something for Marvel or whoever; to be in the business, because it meant that much to them, like us in the beginning. Or worse yet, give away something that they created, or sell it without being aware of what they were doing. The idea with the Creators’ Bill of Rights was to create a list of rights that whether you adhere to them all or not, you were at least one, aware of them, and two, if you went into a company, and you decided to give up all those rights, to work for that company, at least you knew them and you consented to giving up all those rights, and that was your decision. I remember it was really badly received for a number of reasons. We put out this Bill of Rights just sort of saying that “This is what we believe in, and this is what we want to make you aware of, and whether you decide or not to adhere to them, this is a statement by us.” Just about every artist we sent it to said that they were insulted by it because they weren’t part of its creation process and how dare we tell them their rights?! We did not intend it to be “This is the end.” It’s like with a constitution: it wasn’t the end; it was the beginning, something that’s still being re-written and adapted today. Not that this is a constitution, but it was intended to be sort of a growing thing, or just a “how to start” thing.

You see, the Turtles could have taken a very, very wrong turn if we had been less savvy. There was a time early on, Peter David, and Archie Goodwin took a meeting with Pete and I to consider bringing the Turtles in-house at Marvel. Which, you know, there’s still that boyhood fantasy thing inside us that was like, “Marvel! WOW!” And even though we knew fucking better we still went down to the meeting. They said, “Well, you know, we’ll put it in our Epic line, really glossy covers, full color, very slick, we’ll give you an editor, and of course we’d want 50 percent of the profits, and the merchandising.” We were just like, “Fuck that.” But, if that offer had happened really early on, it’s entirely possible that the Turtles would have been another big profit center for Marvel to make millions and millions of dollars on, or perhaps they would have fucked that up, too, who knows.

GROTH: It would be in liquidation today.

EASTMAN: [Laughs.] Yeah, it would be in liquidation today. Yeah, so we had a series of summits that were trying to move this along so we could put it out there for everyone to use or not use. After that it faded away, although a copy hung on my office wall at Tundra. As far as the group went, everybody sort of went on to different things, and even though we still sort of believed in it, and those thoughts were put down for what we thought were good reasons, like a wish list, it never went any further, it was just like, “These are the rights that I think you should have.” End of story.

THE GROWTH OF MIRAGE

GROTH: Rich Veitch says you and Sim got into a pretty pointed argument during one of the summits. He said, “Dave Sim very pointedly began to criticize Eastman and Laird and Mirage Studios. He saw the studio set-up they were building, which was bringing in a lot of young artists from all over the country to Northampton and hiring them to do Turtles comics and merchandising. Dave saw this as a dead-end road. He thought they were getting away from being self-publishers, and it got really intense. And Eastman and Laird took it very personal, and didn’t want to hear it. And the meeting kind of broke on that sour note.”

EASTMAN: That’s probably entirely true, and I think that I’m sure Dave was very vocal about that stuff, and he’s very much a purist that there is no other option than self-publishing, and he’s always believed that even though he’s veered off himself a couple of times, [with] some of his own publishing ventures, which he sort of corrected or whatever. You know you sort of fall off the wagon, you go to Betty Ford, you get back on, and you’re OK again as in, no publishing other than your work. Dave believes self-publishers should be “You write it, you draw it, with or without an assistant, you publish it and that’s it, period. You have complete say and complete control.” The End. There should be no variation or deviation. When some of the artists originally came on board at Mirage Studios, it was because we were expanding publishing, evolving. Michael Dooney would want to do a Turtles story: “I have this little Turtles story I want to tell.” And we would put it in Turtle Soup. But at the same time, Michael was doing Gizmo, Jim Lawson was doing Babe Biker and a couple of other projects. Ryan Brown was doing Rockola. This was in the days when — I mean, the first issue of Gizmo sold like 100,000 copies or something, black and white. It was very profitable. By issue #6, when we stopped publishing it, it was only selling 3,000 copies: the end of the boom and bust. A lot of these guys ended up moving into the area to work with us, doing this and that, came into Northampton just when things, publishing-wise, were collapsing for projects other than the Turtles.

GROTH: Were these Turtles spin-offs, or were these completely separate projects?

EASTMAN: These were completely separate. At first Michael Dooney created Gizmo and we published it through Mirage, Jim Lawson created Babe Biker, and we published it through Mirage, and Ryan Brown’s Rockola as well. And a lot of these guys, we’d become friends with, they were living in our area, they were our bros, and their books were now getting to the point where they weren’t profitable for them to even do: because at first we didn’t pay them page rates. They did ’em, and we gave ’em, whatever, half or better of the royalties and that was plenty. Everyone was making out. This was at a time when the Turtles licensing stuff was going through the roof and we needed quality control. We designed or assisted with the licensing art for the whole TMNT program whether it was a T-shirt designs for somebody in Paris, or toy designs at Playmates, or a number of other products that came through the studio. They all came through our office because we had full approval rights. Even though the licensees would have their own in-house artists, a lot of times they’d send us really shitty drawings. So we figured our own guys could do much better work, and that’s where we sort of evolved into this company that would not only approve this stuff, but we’d also provide art creation services as well. If you want a six-page comic for Turtles Cereal, we would do that in-house, and it would be pre-approved, and the process would be quicker for everyone. It would be done under rates that were their industry standards, which was a lot higher than any comic company page rates, so the guys were very happy. Mirage would take like 10 percent as a sort of trafficking fee, and then the bulk of that fee for doing that service would go to the artist. So they ended up being able to make a lot more money doing Turtles licensing art.

GROTH: But that certainly would have compromised you among the Creators’ Rights purists. Because all this work is work-for-hire, right?

EASTMAN: This is where it gets complicated, and starts getting fucked up. They were, we were caught in the middle. They knew they were drawing Turtles but didn’t own them, and we know they were starting to create characters that we didn’t own which lead to a variety of agreements and work-for-hire contracts. This was all new turf for us. So we just did what we thought was fair. As an example of how we handled the licensing artwork was: if there was a T-shirt that was done for a guy in Paris that they would pay five hundred dollars on, and then that same T-shirt was used by somebody in Brazil, the artist would get paid again. And then if it was used in Japan, they would get paid again. We kept paying them for re-use of their stuff, trying to be fair. They would be paid reprint fees, almost full page rates for reprints of the comics, both Mirage and the Archie versions, even letterers got a full reprint fee when we did collections of Turtles books. Artists that penciled an issue or did other stuff on the Turtles were paid full page-rate fees up front, plus royalties, plus full reprint fees. It sort of evolved into a system from there. Dave, I think, once said, but to me it was very, very awkward argument if you think about it, that “Well, these other cartoonists aren’t doing their own stuff any more, they’re doing all this Turtles shit.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but we’re not putting a gun to their head and saying ‘Do this Turtle Shit.’ They were making really fucking good money.’ Most of them were on the company payroll, and we helped with their taxes if they were on a freelance status. They had health insurance. A lot of them had families now and houses and in the really successful days, they were paid lots of royalties, and outrageous year-end bonuses. Hell, we cared a lot for the guys then!

They were also given a lot of creative freedom and around this time we started this program. They were bringing a lot of great creative elements into the Turtles universe, and when you have to start drawing “lines” of ownership, and copyright and trademark protection, it’s starts getting really kind of crazy! When things are done within the universe of the Turtles, we have to work out in painful legal detail, “These are things that are created within the Turtles universe that we own, and that we don’t own.” Ryan Brown, Steve Murphy, a lot of the guy created characters within the Turtles universe that they still, to this day, own, and they can go do whatever they want to do with them. But there are so many other issues that when it becomes a toy, or a cartoon show, you have to do to legally authorize “around the world” our rights to license it! It costs better than a one hundred and fifty thousand dollars to do a worldwide copyright and trademark filing on a toy concept and name of a character in multiple classes. You have footwear and apparel, you have toys, you have books and other publications, you have movies; there are dozens of classifications! And in order to warrant to the toy company, or to the movie company or the TV company that they can utilize this on a worldwide basis, you have to take all these protective steps or get sued! You have to search it, and you have to file in a hundred-plus countries, and protect it and make sure it’s being utilized properly. So what we devised was this plan, it said, “Look, you create characters within the Mirage Universe, fine, but you have options. If they’re going to become a toy, which means if they’re usually going to become a toy, then they usually become part of the TV series, and so on and so on.” Because those 22 one-minute commercials sell a lot of toys, you know? The plan was, “At the point that it goes from your creation to becoming part of the Mirage Universe, the toy line, you have a decision to make, you can either say ‘Yes, I want it to become part of the toy line, and I’m giving up all rights to my character, but I’m getting 50 percent of everything that’s earned on that character in royalties’ or, if you don’t want to do that, then you keep the character yourself, it doesn’t become a toy.” So they chose and these guys did very well. Ryan Brown designed 20-30 things that became toys and made ... well, do the math. The numbers were phenomenal. We were selling a lot of fucking of toys. These guys could get thirty, forty, fifty thousand or better royalty checks on just their share, four times a year. So of the money that came to Pete and I on any specific toy, the toy company accounted for each separately, and we’d cut a check to the creators for their share. So, like I said, out of the multiple characters that are in the Turtles universe, when Steve Murphy, Ryan Brown or any of the guys who were packaging, or designing in-house, producing the Archie comics series, they had options and there’s still a lot of those characters that they still own! Sorry, I’m starting to repeat myself!

GROTH: It seems to me that with a mass phenomenon like the Turtles, and the fact you have to hire God knows how many artists to crank out the comic books, the newspaper strip — wasn’t there a newspaper strip?

EASTMAN: Yep. Dan Berger was one of the few who used to do the newspaper strip. GROTH: Character studies for various merchandising, you’re on a real slippery slope that eventually you can’t control. I mean, Rick Veitch said, I don’t know if you read his interview ...

EASTMAN: No, I missed that one ...

GROTH: ... he said, “I’d just gotten an after-the-fact work-for-hire contract from Mirage. Some crazy maniac at Mirage I never met in some strange position of power down there was calling me up and threatening me that if I didn’t sign over work I’d done years before I would never see any more royalties. Worse, the contract is more wretched than anything that even DC had ever done to me.” Bissette said, “The fact that Mirage necessarily embraced work-for-hire contracts towards the end says it all for me.” I think what he means by that is that eventually the Turtles became part of the corporate system that employs work-for-hire contracts ...