Rambo 3.5

VALENTI: Let’s use this to segue into Rambo 3.5.

RUGG: OK. The Harry Potter thing is pretty interesting though. I hadn’t thought of that. The Star Wars analogy’s a very good one for it.

VALENTI: Were you into Rambo when you were little?

RUGG: Yes. I was a lot more into Rambo and those action movies than I was comic books.

VALENTI: ’Cause there was that [Rambo] Saturday morning cartoon.

RUGG: How bizarre. It’s relatively disturbing. But all that stuff is like toy advertisements. Those ’80s cartoons are amazing for that…because they would do like 10 cartoons for of all these toy lines, and then whichever toy line was successful, that was the cartoon that would air, and the rest of them would go away. I had a friend that set up an application to go out and scrub the Internet and just save these ’80s toy cartoons…and seeing the ones that didn’t make it…you had never seen them on TV, but now they’re available. It’s eerie, because if you’re a certain age, you feel like you’ve already watched all of these, even though you’ve never seen a frame of them — because they’re done by the same animations studios. It’s just the quickest, cheapest, most unimaginative stuff.

After 9/11, whenever they started saying “terrorist” all the time, all I could think about was G.I. Joe comics, or G.I. Joe cartoons, rather. Because that’s where I had heard “terrorist” as a kid…that’s when I ingested the word terrorist, and then I didn’t think about it for 15 years, and then suddenly it was everywhere.

VALENTI: That’s why I wanted to ask you about Rambo, how you conflated this childlike power fantasy, which is very Reagan…and then you conflated that with George W. Bush.

RUGG: It’s all there. There’s a page with the action figures…there are action figures of both Rambo and President Bush. It’s ridiculous. And then you add in…Reagan’s a really good reference, because of the whole actor media manipulation. I didn’t do anything with Rambo: all that stuff’s already there. Even the Reagan reference makes me think of an ’80s comic called Reagan’s Raiders where Ronald Reagan and Co. become action heroes battling terrorists. Thanks, Rich Buckler.

VALENTI: It’s interesting to me because to Bush, or modern Republicans of the fringier sort, Reagan is Rambo. He’s going to fix it all.

RUGG: I love the reluctant warrior…the man of peace who reluctantly uses violence, except he’s better at violence than anybody else on earth. It’s such an archetype of the ’80s action movies. “I want peace so much, I’m willing to kill you!”

VALENTI: It’s also an interesting power fantasy for a little kid…It’s very attractive to little kids.

VALENTI: It’s also an interesting power fantasy for a little kid…It’s very attractive to little kids.

RUGG: The gun thing is very strong in our culture. Little kids, whether you give them guns or not, run around making guns out of their hands. I think Dan Savage talks about that on This American Life. There’s an episode where he tries to discourage it within his son and not have any toy guns, but his son still does that. It’s such a part of the American myth.

VALENTI: I was watching Punky Brewster, and a little kid that’s, like, 6, he’s dressed like Rambo for Halloween. And I just couldn’t get over that. It’s also how our culture has changed, too, that we would notice something like that and comment on it, where at the time, they’re like, “Yeah, little kids love the Rambo.” [Laughs.]

RUGG: I can’t understand it. And it bothers me to think about too much…because where I grew up, you could still dress your kid as Rambo for Halloween, and nobody would think twice about it. And if you were the one that said, “You know, giving your 6-year-old a fake machine gun to walk around with may be inappropriate,” you would be the outcast. It’s horrifying.

I’m definitely interested in media and how people…you interpret the work differently depending how much you decode the media, how much you’re aware of the messages that are being filtered through media. And it scares me the most in politics, where people are like, “Oh, Bill O Reilly is not a character.” To me, Larry the Cable guy, Bill O’Reilly, Ali G, they’re all the same. It’s all the exact same formula. Right?

I think everybody has a persona. You talk to your parents differently than you talk to your friends. That’s just a natural thing. I don’t know that people put that much thought into it. Some people construct it. In comics, I think Grant Morrison put a lot of effort into that early on. I find it uncomfortable. It’s probably worse now than it used to be. Everybody thinks they know each other because of their online personas.

VALENTI: That and, when I started, somebody might be interviewed once. Now, people get interviewed constantly.

RUGG: I was gonna ask you about that. I feel like, “Why would anybody read an interview with me?” I know what my book sales are, and it’s not like half of my readers are gonna read an interview. Whatever one percent reads it or something, it’s not worth either of our time for that. Because somebody who wants to make comics, like a 12-year-old version of me, now they can read interviews with Dan Clowes, Gary Panter, or whoever they admire. Whenever I was 12, I would find like one interview a month, maybe. So I would read an interview with anybody. It could be somebody whose art I didn’t like at all, but it was a cartoonist talking about his process. I was so thirsty for that knowledge, and there was so little of it out there that I would read any of it. But now it’s like…if everybody stopped making content, there’d still be enough content to last the rest of all of our lives.

VALENTI: I worry about that, too. Because, as an interviewer, you have to think, “What are you bringing to the table?” There’s only one way a cartoonist broke into comics … they have to tell that story over and over, it’s never going to be different.

RUGG: Right.

VALENTI: When I do it, I’m just driven by curiosity. I mean that’s why I interview people. That’s why I’m interviewing you; I’ve lots of questions.

Afrodisiac and Street Angel

VALENTI: But that brings us to the question of distribution and method of delivery versus how you create it. I think you wanted to do Afrodisiac as a 40-issue series.

RUGG: Yeah, at one point, we proposed that to a number of publishers.

VALENTI: What was your idea for that? Would it have been bimonthly, annual?

RUGG: Depending on who published it, it would have been whatever their business model was. Like if Dark Horse, for example, published it, it probably would have been a miniseries, if Vertigo published it, ideally it would have been a monthly. It would have been whatever the publisher picked. The book’s kind of a metaseries of the last decade of the Direct Market, or the last decade of the newsstand market, like, say, from the early ’70s to the early ’80s, mid-’80s, something like that. And so what we did was outlined how it would look if it were a series that was published from like ’72 or ’74 to ’86.

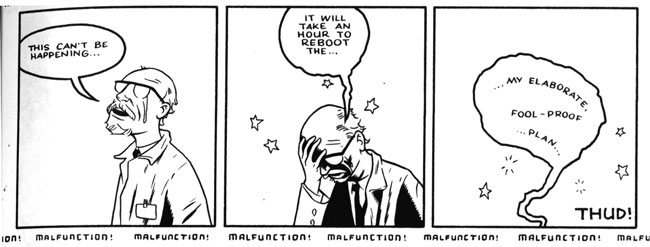

And we came up with this whole series arc, because those books, like Rom Space Knight…that book doesn’t exist today. That would be a four-issue series, maybe, and if it was solicited that way, they might only publish two or three issues of it. Because it wouldn’t have sold well enough, and they would have instant feedback on, “Hey, it’s not selling,” and that would be the end of it. But the newsstand distribution model was so different, that books like that ran for a hundred issues, and they would jump the shark, like we had the last spread of Afrodisiac when he’s in space. That’s our jump-the-shark/reboot/last attempt to boost sales on the character, because that’s what a lot of those books would do. We outlined a big, long story influenced by books like Masters of Kung Fu and other oddball mid-’70s to early ’80s books.

In hindsight, I’m very happy with how it worked out. It was just one of those ideas. It takes us a long time to put these ideas together, to sort of shape them. Afrodisiac took five years probably from the first story to the finished book. And it’s not because it’s five years worth of time in the book. It’s just because you see the character, and you sort of change your…you shape your opinion a little more of it. Street Angel was kinda that way. Once Street Angel was out, probably about four issues into it, suddenly it was like, “Oh, OK. I think I know what we’re doing with this character now.” Because you have to talk about it in interviews, and you kind of figure it out. And after we’ve done that, my attraction to the material changes. Afrodisiac is a study of a material I found interesting at the time. Once I am satisfied with the material, my interests change.

VALENTI: Street Angel is more like the exploitation films I like, because even though the characters are larger than life and cartoony, you understand their motivations. And they have a dignity to them I think is what I respond to in, for example, a Jack Hill movie.

And I was also surprised at how much of Afrodisiac was in Street Angel. How far with the Afrodisiac minis were you before you did Street Angel?

RUGG: That was the first Afrodisiac, Street Angel #5. That makes sense that you would see a Blaxploitation correlation with Street Angel, because Street Angel was our first book, and I think that’s a big quality of Blaxploitation movies, that so many of those filmmakers, that was their first efforts, that was their early efforts. So I love that, where you’re seeing more enthusiasm than craft. That make sense?

VALENTI: Yeah. Well, [even in Street Angel], you really show an understanding of what to show and what not to show. And it’s almost “low budget” in a way: because in theory, you’re a cartoonist and you can show everything. But there’re a lot of times where you just skip the violence all together. But when you show it, you show it so it counts. Was that conscious?

RUGG: Yeah, I guess it’s probably intuitive. I was a huge fan of Frank Miller, and I feel like he’s very good at pacing. In some of the Sin City stuff that he did…I don’t know how familiar you are with all of his Sin City work…but even the Daredevil and Batman stuff he was very good at having those big moments follow a quiet moment, and playing with form. He did...I think it was called “Silent Night,” it was a Sin City one-shot…where the first 20 pages are wordless, and it was the first time I had read a comic that was like that. And I thought, “Man, this is amazing. There are no words, and I’m not just able to follow the story but I’m totally, emotionally attached to what’s happening here.” And I remember the letters columns that followed that were like, “What a rip off! It took me twenty seconds to read this book and it was three dollars,” but to me it was like, “This is a revelation.” It’d be like the silent G.I. Joe issue, right?

VALENTI: Is that Larry Hama?

RUGG: Yeah.

VALENTI: Yeah.

RUGG: One of my favorite things on the Internet, is when someone writes about one of those, some significant issue like that, and how it was influential to them, and how they would just reread it and stuff. I always think that’s pretty fun. But Miller played around with that a lot. I think there was an issue of Sin City where the main character appeared to be hanged early in the book, and then there were like four black, two-page spreads that were just black ink after the opening sequence. Followed by a caption or something of like, “No, it can’t end this way.” And the story continues with the character willing himself to freedom so the narrative can go on.

As a reader, it’s not a technique you see duplicated. I’m sure somebody maybe copied it since, but at the time, that was the first time I saw something like that, and it made an impression. It was something you couldn’t do with Spider-Man. We know Spider-Man isn’t going to be hanged and die in the middle of a storyline (and if he is, we’ll all know about it months before it’s available to read). In Sin City? Well, anything seemed possible.

VALENTI: How would you personally distinguish your kind of postmodernism from, for example, Alan Moore’s or Frank Miller’s?

RUGG: I have no idea. They’re influences…I read their work during a very formative time in my life. So it’s bizarre. I have a friend that I go see movies with frequently. We both saw A Serious Man together and really enjoyed it. I don’t know, two months after we saw it, we’re talking, and he says, “Do you remember this part? This is my favorite part in A Serious Man.” Keep in mind, we both liked that movie but when he described his favorite part, I had no recollection of the scene… as he described it, it slowly came back to me, but here’s a movie I loved, and I don’t even remember his favorite part. So I described my favorite element and he had the same reaction – my favorite part of the movie was something he hadn’t really thought about since seeing it the first time. It was like we watched two different movies.

VALENTI: Quality, and how that affects that experience — sometimes it makes you wonder. You can get so much out of My Little Pony or something, but you can also get so much out of something that’s really a work of art, like Windsor McCay. And that’s the question about art, isn’t it?

RUGG: It’s a big thing, and depending on your age, and when you encounter the stuff and what’s going in your life, you’re going to respond to different parts of it. I have a friend who was reading Crumb when he was 12. I was reading Stephen King and Rob Liefeld comics when I was 12, and it’s like, man, what a different toolset you have if that was the stuff you read when your brain was in that impressionable period.

VALENTI: Yeah, it’s interesting to me too, because I think for a lot of kids their Spider-Man Underoo experience is going to be manga.

RUGG: Yeah, I love it. You already see it. People make comics now that have no Marvel, DC influence whatsoever. They may have never read a Spider-Man comic, and they’re making comics. It’s so great. It’s amazing. And that’s not a criticism of Marvel/DC storytelling. It’s a criticism of a system that discouraged diversity.

The Spider-Man Tangent

VALENTI: Actually, this is just a tangent, but you said you never got Spider-Man in another interview. Or what was it you said about Spider-Man…

RUGG: Probably that I hate him or something.

VALENTI: [Laughs.] I was just wondering if you could explain why that…

RUGG: Sure. Here’s a guy who can beat up anybody, right? So you go from being a nerd to being able to handle yourself in a fight against literally anybody on earth. You go through your life and defeat every villain in the Marvel universe 50 times over. You’ve saved the world, beaten up guys that are jerks, and you’re married to a supermodel. You know, your confidence is high. You can’t be this woe-is-me nerd. That’s just not who you are. It’s ridiculous. It’s that thing…people will relate to whoever, Charlie Sheen. That’s probably not the best example. But people relate to these celebrities, right? They project themselves onto these total strangers.

VALENTI: Yes.

RUGG: Why? You have nothing in common with them. Remember when Angelina Jolie and Jennifer Aniston were on tabloids for a couple of years? People were like, “Oh, Angelina Jolie is this terrible person who steals Brad Pitt.” You don’t know Jennifer Aniston; you don’t know either of them. How do you have any emotional investment in this whatsoever? Why do you spend one second thinking about it?

VALENTI: This fascinates me, because I think about tabloids a lot. It’s like wrestling, and people just play characters. You’re the bad guy today, but tomorrow you might be the good guy. And if you look at the syntax and the diction of how tabloids are written... It’s basically a Betty and Veronica comic for 50-year-old men and women.

RUGG: It obviously fulfills a role, because it exists for every demographic. Like you said, wrestling…now reality TV shows, Jersey Shore, tabloid stuff, soap operas for another generation. I don’t understand what function it’s serving. Maybe it functions as a replacement for a society where we’re all so busy with careers we don’t have time for real family interaction or meaningful community in the real world. I don’t know. It’s very bizarre. Maybe it’s a safer way to interact emotionally — we don’t open ourselves up to personal injury by living vicariously through others.

VALENTI: People turn it into their own story somehow, based on just these cardboard figures. It’s almost like playing with action toys.

RUGG: One last Spider-Man knock. The lack of character development coupled with a long-term readership annoys me. If Spider-Man comics were cycling through new batches of readers every few years, it’d be one thing — keep the character the same, repeat stories…but that’s not what’s happening. Spider-Man isn’t a character. He has no arc. He does not develop or grow or change. He’s a logo on children’s underwear. Am I the only one that finds that unsettling? I was at a party around the time of the second Spider-Man movie. And on the way to the bathroom, a 35-year-old, father-of-two cornered me on the stairs to tell me how great Spider-Man 2 was and that it made him “want to be hero.” Really? While you’re waiting to foil a mad scientist with robotic arms and a shitty nickname, how about if you apply that obviously substantial intellect to solving our pending global financial meltdown?

(Continued...)