I conducted this interview with Jerry Moriarty in 2008 at his studio in midtown Manhattan. I consider part of my function as that of an evangelist on behalf of art I love, and therefore think you ought to love, which is the spirit in which I present the following interview. My original plan, about which more momentarily, was that this would merely be the first of several long interviews that I would stitch together into one massive gab-fest. Too few people know Moriarty’s work —which is true of many superlative contemporary cartoonists, of course— and I thought that by publishing it in the bi-annual print edition of The Comics Journal, I could introduce him to new readers and give him some deserved recognition.

I conducted this interview with Jerry Moriarty in 2008 at his studio in midtown Manhattan. I consider part of my function as that of an evangelist on behalf of art I love, and therefore think you ought to love, which is the spirit in which I present the following interview. My original plan, about which more momentarily, was that this would merely be the first of several long interviews that I would stitch together into one massive gab-fest. Too few people know Moriarty’s work —which is true of many superlative contemporary cartoonists, of course— and I thought that by publishing it in the bi-annual print edition of The Comics Journal, I could introduce him to new readers and give him some deserved recognition.

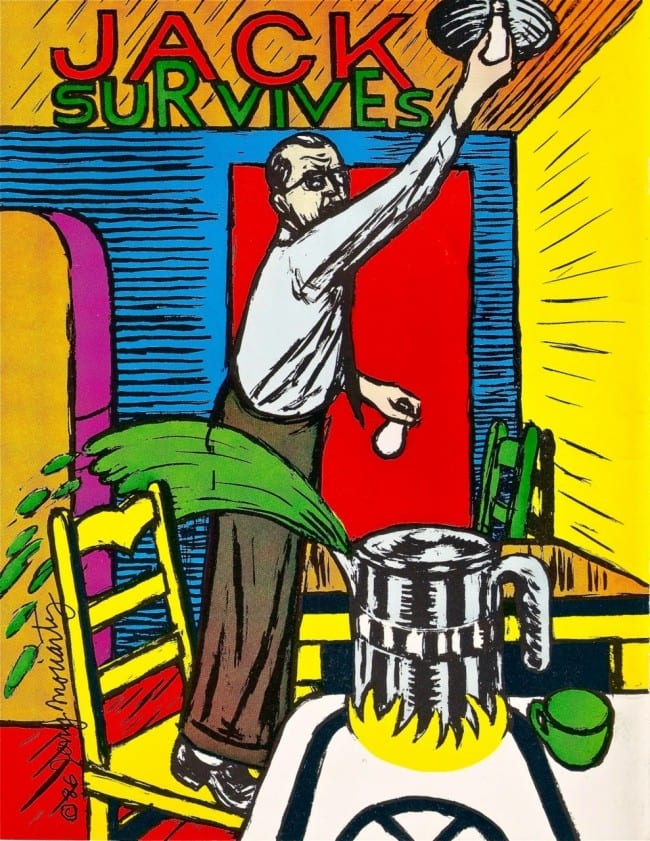

Moriarty is not exactly a cartoonist, per se; more of a painter who detoured into cartooning when he drew a remarkable, painterly, strip titled “Jack Survives” about he and his father for Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly’s Raw magazine in the mid '80s.

Moriarty was born in Binghamton, New York, in 1938. In this interview, Jerry talks about his upbringing and his early life through his enrollment at Pratt in New York in the late ’50s. Briefly, then, after he graduated from Pratt, he worked as an illustrator for “girlie magazines” and tinkered with abstract art; but, as he wrote, “One night he decided to put four paintings together to make a square of four walls. He sat in the middle and awaited revelation. It didn’t come. Instead, the abstract canvas walls spoke to each other and left this kid out. Saddened at his uncoolness he returned to ‘content’ and tried to find its meaning in him. The kid swore he would never be seduced by Art or cool again…” And it appears as though he hasn’t. He has had occasional gallery shows —in Soho in 1974, in Chelsea (NYC) in 1984, at the School of Visual Arts Museum in 1999, and at The CUE Art Foundation in 2004. He does not sell his art and he does not navigate the world of fine art very adroitly, which may be to his credit. He is not only marginalized, but may be self-marginalizing, which may also be to his credit. He has taught at the School of Visual Arts from 1963, but was “fired” in 2012, being told that the school: “has no need for a class that involves drawing without using photo references.”

About the interview: I had intended for the interview here to be the first of several long sessions, but, alas, like so many well-intentioned plans, it went awry. Not to put too fine a point on it, Jerry got pissed off for two reasons and decided not to continue the interview: a) He felt that I took too long to transcribe this interview and follow up with the 2nd (and 3rd); and b) that that therefore evinced an “I don’t think he is significant enough to bother with” (to quote Jerry) attitude from me toward him and his work. I cop to the first charge. The interview you’re about to read is only about two-thirds of the interview I’d conducted, because unbeknownst to me during the interview, the batteries of my tape recorder were running out, and the last third didn’t record at a speed that was decipherable. I felt so badly —or demoralized— about this that I dragged my heels getting it transcribed and copy edited so that Jerry could look it over. On the other hand, I knew what my own internal deadline was and didn’t think Jerry was in any hurry — I thought we could take our time, so I didn’t feel the same urgency Jerry felt. The second charge, however, couldn’t be further from the truth: I love and respect Moriarty’s work and my whole purpose was to give him his due as best I could: My goal was to publish a lengthy interview with him in the print edition of The Comics Journal along with a mountain of his drawings and paintings, showing the variety of his artistry, so that a wider readership could discover him and appreciate his work. Well, that didn’t work out, but fortunately, here is the interview I managed to do.

I love Moriarty’s guerilla-style, almost stream-of-consciousness conversational style. It’s filled with piquant observations of his changing social landscape and shrewd self-appraisals. I hadn’t gone into this first interview with an agenda, but as it turned out, we spent most of the time talking about Jerry’s life and his search for an identity. I think it’s fascinating stuff because his search to find himself within a succession of social milieus parallels his search to find himself as an artist. Jerry is a great, insightful talker and I’m only sorry there’s not more of it.

But, there is more of Jerry Moriarty here, and I recommend you see as much of him as you can.

Gary Groth, January 28, 2013

MORIARTY: See a Munch show at the Museum of Modern Art, and I love Munch. Munch is one of my more recent — not recent, maybe five years ago —

GROTH: That’s recent.

MORIARTY: I got hip to Munch as a guy who somehow made emotion visible even in the things he did, and he did it 1892, I mean, you go wow. This looks so far out even compared to the early Cubists’ stuff. I mean, Matisse is still pretty far-out looking. I don’t even know how I feel about him. He’s starting to get my attention, I got to say. I’m surprised and pleased with that. I’m pleased that in my old age, I’m starting to see things that I couldn’t get to unless I was pretending to be cool: now I’m actually understanding some of that stuff. I’m pleased that my brain hasn’t turned to cement at this point. I feel it sometimes, my brain farts. I forget names and do that kind of stuff.

GROTH: But you think you needed the cumulative knowledge and experience in order to appreciate certain people?

MORIARTY: No, I think what’s happened is I just got smart. Just straight-out, flat-out got smarter. Not smart — smarter. One of the things I always tell my students is, you get smart with art. Meaning, when they’re making the picture, they start out, where they were, in that frame of mind, and that intelligence functioning, and then as the picture goes along, they get smarter, because the picture is directing them in certain ways. I mean, it’s them, of course. It’s a subconscious thing, I think. And then they’re relating to it and keep things and leave things, and they make decisions along the way. It’s like a real chess game going on.

GROTH: They learn by making.

MORIARTY: Yeah. And at the end of the picture, they’re smarter than they were when they started. But between that and the next picture, they’re as dumb as they were before. You know what I mean? The pictures make them smarter: maybe not quite as dumb as they were.

GROTH: They don’t retain the smarts?

MORIARTY: They retain it to the degree —

GROTH: Wouldn’t they?

MORIARTY: The experience does have a residue, yes. There is something about that. But it’s not like you have that creative intelligence up at the top like you were at the end of the picture, when you decided that it was finished, and you completed the experience of it. So I just flip back to my civilian self, and then I sit back and I look at the pictures and sometimes I can’t understand if they’re any good or not, and sometimes I feel that they really are good when in fact, they probably are not so good. The ones I really like I’m really distrustful of, because I shouldn’t know that much about them already, it takes time. It’s like when you write something, sometimes you’re not sure about it, and then you look back and you realize, “Hey, that was a spontaneous, good moment there.” And it’s a jazz thing too: it’s improvisational luck, or improvisational things.

GROTH: I assume it depends on the picture, too. I assume you could get stupider at the end of drawing a picture, if the picture were bad enough.

MORIARTY: No, the bad pictures really teach you. It teaches you because you do everything to save it. It’s like the lost sheep, you’re trying to save this sheep here, and yet it still goes down the toilet. My feeling is that there’s a nemesis planet functioning here: you know that planet on the other side of the sun, in the exact same orbit that we are? That’s why we can’t see it? It’s on the other side of the sun.

GROTH: Perpetually, yeah.

MORIARTY: And that’s where the art gods are. And the art gods are fucking with us. And they say, “What’s this?” Whack! And so you get this bad idea. The art gods give you a bad idea. So you’re working on this bad idea, thinking all along it’s a good idea, because why would you even start it?

Then you get to that point where it’s pushing back and it’s not functioning and you do everything to save this thing. That’s where your chops start to fly, because you’re trying to save this sinking ship, and so at the end, you’re pretty strong, but the picture is dead on arrival. [Groth laughs.] Or, in fact, it may be actually a new experience, it may be really a good picture, but you know pictures — I do enough bad pictures to recognize that. I’m totally pissed, I’m not happy at that, even though I know they’re possibly a reward.

Because I’m only as good as my last picture, and if it sucks, I’m fuzzy and blurry [Groth laughs] and I’m not the me that I would like to be: the hero me. Because I make art, that’s the hero me. When I’m not making art, it’s the fuzzy pretender, the poseur. So when I’m making art, I’m the hero-me, but I don’t want to make art all the time, because I’m also a lazy bastard, you know? I have art guilt, so I make art because I get this kind of twinge of, “I’m out of focus, I’m blurry, I’m not me, and get off your ass and do something.” Then I get to work, somewhere near that thought, but not immediately. I put on the brakes and the gas at the same time.

There was a jazz musician that told me about what he called a geyser theory. And the geyser theory came from the notion that when you get into a slump, it’s like your brain telling you that it’s tired. Actually, this is something I came up with later, but it’s similar to what he was saying. You really shouldn’t try to fight that, you should let your brain rest. So when you’re ready to start work, you don’t really start it. You start building up this pressure inside you. You put on the gas and the brake at the same time. And finally, you can’t stand it any more, you take your foot off the brake. And then BWAAAAM! You know, you’re out there, like a shot. And it’s a geyser theory of creativity.

And this guy was like Burton Green, he’s like a far-out contemporary piano — I think he’s still around. He once came to SVA. I was someone who had been given the assignment of putting on jazz concerts there. Somebody else got him, and I had no clue, and he was really incredible. It was during that wacky — he recorded on the ESP label, which was known for far-out people. I think he had a trombone player and a sax player, or a trumpet player and a sax player, and he banged on the piano with a hammer [laughs]. It was crazy. He walked around, picked up the fan: started walking around this amphitheater holding this giant fan. It was performance, but he really did have — anyway, intermission time, he was trying to find the connection between art and music, how they were both in an improvisational relationship. I always believed that, anyway.

I loved hearing him talk like that, because even artists don’t talk like that enough, for my tastes. Talk about the creative process in any way. And we’re not particularly articulate, so it’s usually better to hear a writer talk about it, because they’re going through the same thing, like you guys work all alone late at night. Mostly writers work early in the morning, I think. But there’s no one to see what you’re doing while you’re doing it, and it’s all on individual judgment, there’s no response from an audience, so to speak, out there…immediately, anyway.

GROTH: Do you think all the arts have essentially the same creative process: writing, painting, making music?

MORIARTY: I think that they share. I think collaborative arts are different. I recognize certain tricks when I see Actor’s Studio guys on TV talking about their process. Christopher Walken, on one of the shows, he said something about, they’d all get their scripts, and he would go through his script and take all the punctuation out, so he wouldn’t know if it was a question or whatever. And so he delivered a line without any knowledge of whether it’s a question or exclamation, so the actor he’s playing to would freak. And I just love that, because it’d make the other actor improvise, somewhat. Of course, he’s in the dark himself, because he took all the punctuation out. I think that’s nice.

Another actor said that, on the stage before an audience, if you got to the point in the part where he’s supposed to cry, he doesn’t cry, because he wants the audience to cry — because if he did cry, then the audience wouldn’t have to cry, because he fulfilled what the need was. I love that, so when I hear these things, I find connections. But I think the real distinction is collaboration, because they have to work with someone else in that moment, whereas writers and artists generally don’t. So, it’s like a tightrope, there’s no support at all. No net at all. You survive the fall, but you know the fall exists. There’s no support structure for you. It could be a lifelong thing, like the Henry Darger life — I don’t know if he sensed that. I think there are differences. Jazz comes the closest to my sensibilities.

GROTH: Why is that? Because jazz can also be very collaborative —

MORIARTY: Yeah, that is.

GROTH: — performing in front of an audience.

MORIARTY: Yeah, that is, and there is that sense of collaboration, but there’s more. The newer jazz has left the swing world, your friend Artie Shaw’s world. It’s left swing behind, as he would have gone, because he did do the next things, each time. He would have understood that, I’m sure.

GROTH: That’s right. He desperately wanted to leave that behind. They didn’t let him.

MORIARTY: Yeah. So the Anthony Braxtons, the Roscoe Mitchells, these are all names. These are not young people, like Anthony Braxton is 60 years old now, and Roscoe Mitchell’s gotta be somewhere near there. There’s Evan Parker, an English guy who plays soprano sax, and tenor. They have real music understanding of things, but my use of their work is when they play solo stuff. Not solo in a group, solo literally. They do whole albums as solo sax playing. It’s all saxophone for me, because I can’t abide any other instrument, for some reason. It’s the narrowness of my collecting [laughter]. It’s like alternative-comic people won’t give any attention to Marvel or DC. It’s as simple as that. [Groth laughs.] I’m the same way. I’m glad I’m that way, because it says I’m still in an opposing mode. Like, this is the mainstream and this is where I am.

GROTH: That might be even more narrowly focused: just the sax.

MORIARTY: Yeah. Just the sax, I dislike drums, intensely, because they fuck up the sax solo — especially the ones that hit the cymbals, and with CD recording now, you really hear that higher thing, where you didn’t used to hear that so much in LPs. You heard ting ting ting, it’s like a car alarm in my ears, turn off the fucking car alarm, you know? [Groth laughs.] Because I want to hear the saxophone guy do his thing. So drummers, there are some who are giants, but I don’t know who they are — I can’t give you a name now. But mostly drummers are just to be tolerated. And they should never be given sticks, just give them brushes and say, “OK, tsch tsch.” Even the brush on the cymbal isn’t going do anything. So, that’s my feeling.

And then, trumpets, they’re too harsh for my ears, outside of Miles Davis, which is a conservative player, a commercial player, basically. But an inventor still. I mean, he sounds more like a sax — and he loves saxophone people. He always had great — Coltrane, Wayne Shorter — whoever he had with him was really top of the heap, saxophone-wise. So I always would get good sax with Miles.

GROTH: How about the cornet?

MORIARTY: Any of them, whether it’s mellow, or like a cornet’s a bigger sound, or the flugelhorn … I love them classically. You know, David [Brain], or whoever is playing Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto in D or whatever, [sings] Daa, DA da, dun duuun dun ta; I mean, I just love that. I love the flute in classic; I hate it in jazz. I love it classically, you know: piccolo, whatever, a Vivaldi piece, a baroque thing, even modern music to a degree. For me, it’s a chops instrument, so these people playing it with perfect chops. When I hear the saxophone played with perfect chops, I hate it.

GROTH: Oh really?

MORIARTY: I hate perfect chops on the saxophone, because it’s sort of like …

GROTH: Soulless?

MORIARTY: Yeah, it’s brought into the repertoire of, this is how one was really trained and taught. The saxophone doesn’t even belong in the orchestra, originally, it’s been allowed in through Ravel [who] wrote something, and Stravinsky wrote some things, so the alto saxophone’s been accepted into it. You know, the bassoon and the oboe and other instruments do what they think the saxophone will do. So I like its not-belonging kind of thing. Sort of like comics in the old days of comics, when comics really were outlaw. Even mainstream comics were outlaw. It’s like, “Don’t even like them.” So jazz and comics were outer-side. Rock and roll had the main place, or classical music, jazz was like, you wouldn’t find …

GROTH: Disreputable.

MORIARTY: Yeah, or it would be such a small little …

GROTH: Marginalized.

MORIARTY: Yeah. Or you couldn’t even find the albums. The catalog would be full of rock and full of classical. There would be this narrow place called jazz. You might as well say “other.” That’s what jazz seemed to be, unless it was mainstream, like the Kenny Gs of the world kind-of-jazz. That’s always going to be acceptable, but only because it doesn’t stimulate anger or frustration or any other emotion. That wouldn’t be acceptable.

GROTH: What do you think of masterly sax players like Ben Webster and Coleman Hawkins?

MORIARTY: Oh, Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster, I was very much into them, and then all of a sudden I just shut down. I mean, I’m sad. I’m not going to say they suck or anything, because they did top of the line, in their time, and they were right. But if I didn’t shut down on them, I couldn’t have gone to the next place. It’s fairly recent, that I’ve, all of a sudden — it’s because of the Internet. I started buying these CDs. I didn’t even have CDs; I didn’t even have a CD player. So I started looking around at names I did know. Ornette I already knew, speaking about Coleman — Ornette Coleman. That’s the only person left from that period that is still — aw, I don’t think you ever can catch up with him. He’s not that far out, but he’s just exquisite. He just had a new album come out, called Sound Grammar. On his own label again, he’s a guy who publishes his own things as well, like his own label called Sound Grammar. He’s 76 years old, and I’ve heard little takes online, and it’s just there, it’s all still there, and new, as well.

GROTH: It sounds like you’re into innovators; [Ornette] Coleman was a great innovator all the way back to the ’60s, right? And Braxton, certainly, is pushing it as far as he can push it.

MORIARTY: Yeah, oh yeah. And Roscoe Mitchell’s my new fave. He was from the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and …

GROTH: So what do you like about them, do you like the fact that they’re blasting apart old idioms?

MORIARTY: There is a sense of craft that’s allowed to be buried. You sense it’s still there, because every once in a while you hear it. One CD was so easy to get, it was so cheap, and I wondered, “Why is this Anthony Braxton album only six bucks?” So I got it, because I couldn’t lose, because I have this two-tray CD recorder, I don’t do it off the computer but I do the off the stands-alone thing, and I take the parts, only saxophones, out of things. So I only have saxophone CDs. I just have pure things.

So when I’m working, I’m listening to music, I’m just hearing absolutely the stuff I love. So I’m high on that alone. So it supports me and I float with it, it’s flawless. And I hear deeper, too. I hear the things I knew I liked, but then I didn’t know why, and I know a little bit better why. But there’s not everything there, there’s definitely areas in Braxton, lots of areas, that are still way too far out for me — I can’t get there — and same with Roscoe Mitchell. Maybe some day I’ll get there, or maybe it’s just not going to be the thing that I’m going to get. But the essence, I do get.

GROTH: By not “getting there,” you mean you can’t comprehend what they’re doing?

MORIARTY: It’s still another taste. It’s like Matisse. Matisse is someone I’m strangely interested in now, and I think comes along with the notion that my mind is opening up again; I went to this MoMA show, and I saw Munch, and Munch disappointed me.

I would have liked to have seen that show outside of seeing the books on Munch. I would have been interested, but not overwhelmed. But the books on Munch, with great reproduction today, you can do it so beautifully, and it’s in your lap and I can actually look at it and contemplate, like I would a comic book, and I can look at it and really enjoy it. I built up this whole dialogue with Munch in my head, and read as much as I could about him, so when I go to the MoMA show and there they are, the real things, they were bigger than I thought, even though I saw the dimensions in the books.

He was not direct to my brain. First of all, because I’m in a room full of people, and it was a popular show, and it was the new MoMA, so we’re in the new MoMA now. I walked away not retaining anything of unusual import from it. I think it’s the same thing with music: live music doesn’t interest me as much as recorded music. I go for the ambience, you know, jazz club or whatever, and I love that, but …

GROTH: But that’s because you find it easier to contemplate it in isolation?

MORIARTY: Yeah, because I have kind of an anti-theater sensibility, which blocks a lot of stuff out. I can’t stand opera. I like Mozart, but I couldn’t stand Cosi fan tutte, or Don Giovanni, which is supposed to be the best opera ever written to people who like old opera. You can have a case for Philip Glass or something if you like more contemporary stuff, but that’s supposed to be the best. As soon as the voices come in, I’m out of there, because I can see them in their costumes mentally. If I went there, I’d have to deal with theater. I’d have to deal with people with these over-trained voices for my taste, and I wouldn’t hear the music, I would hear these other presences which are disturbing to me. In art too, installations, I can’t stand installations, because to me that’s theater. Sets, these are props, these are not things that are giving you illusions, they’re facts. You see an installation.

I don’t like sculpture for that reason. It sounds like a closed mind, but it allowed my mind to be open to other things if I just stop trying to work on stuff that’s not going to reveal stuff to me. I’ll walk up to a sculpture — I mean, I love Giacometti, I’ll say that, because Giacometti is almost not a sculptor. He’s so skinny, the things are so skinny, it’s almost as if I’m not even a sculpture: I’m a line in the air. And you go, “Yet I know you’re three dimensional, but you’re fooling me. It’s an illusion you’re giving me.” That I like. So sculpture isn’t totally shut down, it’s the fact that when they become realities, physical objects, if they fall on your foot they break your fucking foot, that’s too real for me. If a landscape fell off the wall, in the Metropolitan or any place, it hit my foot, “ooh that hurt.” It’s a whole landscape, but it didn’t hurt my foot, because it’s an illusion, it’s not a real landscape.

So I think as much as theater gets into it, meaning “real,” and then something bigger than real, and it’s like dramatically bigger. Plays I have a problem with.

GROTH: You can’t go to author’s readings too often.

MORIARTY: I like them on CSPAN, that’s cool, because they’re on a flat screen. I don’t know if I’ve ever been to an author’s reading, but if I imagine the screen’s there instead of me, then I can deal with it. I can go to jazz clubs, I haven’t recently, I haven’t in years, to tell you the truth. I used to go, you saw my jazz drawings. I used to go, and I would be there but I would not be there because I’m jamming with them by drawing them. I’m not just the passive audience. That’s another thing, I do like passivity, to be there as this audience. I have the old punk-group attitude, this group I occasionally play with that Patrick McDonnell had called Steel Tips. They would let me play, I’d be the Rubber Tip, they were the Steel Tips. CBGB’s, whatever. Their attitude was, fuck the audience, we despise you. The audience loved it. One of the people in Steel Tips used to piss on the audience, literally drink beer and piss on the audience [laughs]. Take out his joint and piss. And he’d go, “How does an audience even tolerate that?” Even as a punk audience.

GROTH: You were part of the band?

MORIARTY: I was like the old guy who played an acoustic instrument that they allowed, because Patrick was in my class with Kaz and all the other people, different times. Joe Coleman was in the same class with Patrick and he was part of the group, too. He sang.

GROTH: Really? Joe was?

MORIARTY: He didn’t do geeking stuff then. Joe did a routine once that I thought was brilliant. He made up these songs, and he’d come out and sing, and he looked like a Wild Man of Borneo, he’s got this giant hair even then. He was even wilder. He has this rich hard tempera color, which is in jars, that people had in grade school, it’s really liquid tempera, and he would have blue and red and yellow and green, and as he’s singing he’s pouring it over his head, color is running down and he’s spitting it out at the audience. It’s water soluble, so he’s getting covered with blue. Then he’d pour yellow and there would be green now coming down, because yellow and blue are mixing. It was brilliant. I loved that. I was actually in the audience then, just to watch it. And afterwards, back in the dressing room, if you could call it that at CBGB’s, it’s just right behind the band thing, it was this little niche. The white of his eyes were yellow, not from the paint, but from some kind of chemical reaction to it. [Laughs.] It was strange, he looked like …

GROTH: Sort of spontaneous jaundice?

MORIARTY: Yeah, yeah. Then he used to light his shirt and explode, he had this explosion thing. That was part of his act for years after that, too. Yeah, he was part of the group. And that’s why I could be there, because no one knew who the fuck I was there, I was just standing there playing a — and I couldn’t even come near to playing what I can do now, we’re talking 1979, this is during the time of Blondie and the Cramps, and those people, and The Dead Boys.

The Dead Boys played opposite, this was really into punk time. The lead singer was a wannabe Mick Jagger. He’s really skinny and I think he OD’d finally, but he had a song called “Catholic Girl,” something about how he liked to fuck Catholic school girls or something like that. And the lead girl singer in the Steel Tips who is now Patrick’s wife, wore a Catholic school girl outfit, plaid skirt, and she’s a cute little button thing, and she’s singing these nasty songs. You could see it coming a mile away, but then it was still kind of new, you’re talking about 1979. Not really super new, people who were there knew what they were going to hear, because they were there for that reason.

So she decides she’s going to attack this guy because this first set was over. I had played with them that night, and I think the second set was The Dead Boys, and so when he got to that song, she was going to jump on the stage and beat him up — because he was so skinny, and she wasn’t big, she was really small, but she could probably do it. But she wanted a way to back him up, and the Boys’ singer was this giant guy, who was like Tommy O’Leary, they called his family “The Fighting O’Learys,” because everyone was like this big Irishman fighting each other, relatively young people. He loved rock and roll, and he was always getting in trouble. And he was the guy who used to piss on the audience. And so he’s going to jump on the stage if he needed to. But she said we all got to be around the stage in case somebody in the band gets wacky, because I’m going to jump on the stage.

And of course, she jumped on the stage, she grabbed the microphone away from him, and he kept pulling on it, and so she let it go and it whacked him right in the face, and it started to bleed [laughs]. It was a punk moment.

The reason why I like that idea, the punk idea, was it had some of the notion of the jazz that … there used to be a club called Slugs and places like that that was not really sophisticated, it was a sawdust-on-the-floor kind of place, and CBGB’s was clearly that. It hadn’t changed in years. It hadn’t been around that long, but it was pretty much the same.

So Patrick being in my class, he loved jazz, he loved Zappa more than anything. But he liked jazz, he liked strange things, And he liked lots of very interesting alternative rock, Captain Beefheart and things like that. And I wasn’t aware of any of that stuff; I had just totally given up on rock ’n’ roll, because I was hearing arena rock all the time. It was the day of Queen and Kiss … talk about theatre. And all that stuff. It had gone into bigger venues, and punk was the savior of that. It was low-fi, not stereo, and garage bands from New Jersey and really it was necessary, it was the perfect thing. It gave me faith in rock ’n’ roll.

GROTH: It was like an antidote?

MORIARTY: Yeah, it was better than … I hate disco, which was the other thing that was going on. Preppies were going to disco, and the Warhol crowd was going to disco, and punk was kind of real people, working people in a sense. Not that there weren’t any working people in the other arenas, but they went that way instead of this way, and so it was refreshing to be included in that. And he would just say: do it, play whatever you want, it doesn’t matter.

GROTH: Who all was in the band?

MORIARTY: Patrick McDonnell, his brother Mike, Karen O’Connell. [Patrick McDonnell] and Karen wrote the book on [George] Herriman, that very good book. And that’s way early. Joe Coleman … I can’t remember the bass player … Patrick O’Leary, and that was it. And me every once in a while, maybe four times. Max’s Kansas City, too. We played there with them once. They were almost the house band at CBGB’s. Hilly [Kristal] really kind of took to them.

So I would be visiting or something, and he would say, “We’re going to play now, you want to get your horn?” I’d jump in a cab, I’m in Manhattan, so I’m just all excited to get the horn. It wouldn’t matter, no one’s going to hear me, and I’m just going to have fun being up there and just look like the old guy. And I was 40, so I wasn’t as old as I am now [laughter.] But still it was fun, because I like the people. They didn’t demand anything of me, and they knew I wasn’t going to be a problem for them, and so it was OK. The irony is that some of the audience would come backstage, which is just this little room on the edge of the stage, it would be on the way to the bathroom. There’s not even a door, just a little curtain pushed back. All crapped up and stuff. And they’d come to me and say, “Oh I really liked you.” And your own eyes are rolling — they couldn’t hear you, of course. They’re just being nice about it. But it was fun.

(Continued)