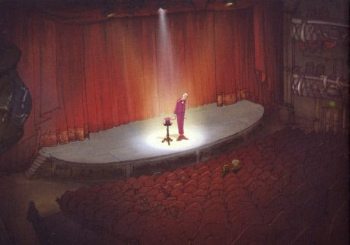

I'd like to be able to say Sylvain Chomet's The Illusionist is a better movie than the recently coronated Toy Story 3. Not that it isn't a fine thing on its own terms. Based on an unfilmed script by Jacques Tati, The Illusionist is the story of an old and not particularly skillful magician eking out a marginal existence during the dying days of variety entertainment. In a last-ditch engagement at a pub on a Scottish island so isolated that the people enjoy his act — the end of the world almost literally — he takes a liking to Alice, a waifish young scullery maid. As she doesn't have a decent shoes to wear, the magician buys her a pair as a parting gift. Following him onto the ferry to the mainland, Alice essentially adopts the magician as a father figure, and he acquiesces. The life he brings her into is only marginally less dire than the one she escapes. They set up in a theatrical boarding house frequented by other dead-enders of the variety stage, remnants of a time when performers with a marginal amount of talent could make some kind of living with it. Now it's a morgue where they stay until they realize their living is dead. In order to maintain the illusion that Alice might one day make their relationship something more romantic, the magician sneaks out at night to take menial work so that he can continue to buy her gifts. As he improves her dress and deportment what he is doing is not what a lover does but what a father does — he's putting his child in condition to find a suitable mate. When she finds a young man who can protect her and show her the ways of the world, when he realizes the only role he can now have in her life is father of the bride, the magician abandons all his illusions, sets his stage rabbit free (or perhaps more accurately, leaves it out to die), and boards a train to nothing in particular.

I'd like to be able to say Sylvain Chomet's The Illusionist is a better movie than the recently coronated Toy Story 3. Not that it isn't a fine thing on its own terms. Based on an unfilmed script by Jacques Tati, The Illusionist is the story of an old and not particularly skillful magician eking out a marginal existence during the dying days of variety entertainment. In a last-ditch engagement at a pub on a Scottish island so isolated that the people enjoy his act — the end of the world almost literally — he takes a liking to Alice, a waifish young scullery maid. As she doesn't have a decent shoes to wear, the magician buys her a pair as a parting gift. Following him onto the ferry to the mainland, Alice essentially adopts the magician as a father figure, and he acquiesces. The life he brings her into is only marginally less dire than the one she escapes. They set up in a theatrical boarding house frequented by other dead-enders of the variety stage, remnants of a time when performers with a marginal amount of talent could make some kind of living with it. Now it's a morgue where they stay until they realize their living is dead. In order to maintain the illusion that Alice might one day make their relationship something more romantic, the magician sneaks out at night to take menial work so that he can continue to buy her gifts. As he improves her dress and deportment what he is doing is not what a lover does but what a father does — he's putting his child in condition to find a suitable mate. When she finds a young man who can protect her and show her the ways of the world, when he realizes the only role he can now have in her life is father of the bride, the magician abandons all his illusions, sets his stage rabbit free (or perhaps more accurately, leaves it out to die), and boards a train to nothing in particular.

The reason I'd like to be able to say Chomet made a better movie than Pixar is that Chomet is the one I count on, and perhaps the only one we can count on, to make the case for traditional two-dimensional line animation to an increasingly indifferent public. Three-dimensional CG animation is a new art form whose possibilities are still being explored, and this creates an excitement that is undeniable, but I have no doubt when the territory is fully mapped it will be revealed as neither as high or as wide as that of the predecessor form. (Witness the hard time computer animators have with depicting living creatures, or at least living creatures that don't have exoskeletons.) Unfortunately it seems likely now that a whole generation has now grown that thinks of line animation as the cheap kind that's done for television. Or the kind that's done by the Japanese. The frustration for the partisan of tradition could not have been greater than with last year's The Princess of the Frog, which in its best sequences amply demonstrates the superior qualities of line animation, but which in its utter emptiness — seeming as it does less a movie as a product placement for itself — fails to exercise the form's ability to engage an audience.

Nor was Paul and Sandra Fierlinger's My Dog Tulip of much help on this score. The television animation of the 1960s was often derided as illustrated radio, a reference to the small part the actual animation played in the appeal of these shows. My Dog Tulip might be described as an illustrated dramatic reading. Most of its appeal is in J.R. Ackerley's text and Christopher Plummer's performance of it, with the animation seldom doing more than showing you what you've just heard. The credits declare that no paper was used in the creation of the film, a strange thing to brag about it seems to me, particularly since a number of scenes are made to look as though they were drawn on notebook paper. It's hardly surprising since the animation frequently has that unnaturally fluid look that the computer animator must always fight or, if the animator is Paul Fierlinger, surrender to.

And so I count on Chomet. The Illusionist is a lovely thing and a gentle thing, and these are two things that computer-generated movies generally are not, but it is a little thing, and I fear a minor thing. For while it is telling you something true while Toy Story 3 is telling you something that isn't, it's also telling you something you already know. Toy Story 3 is a big movie about big things, less from any deep thinking on the part of its creators than their determination to carry their premise to its logical conclusion. I was not being at all facetious last year when I wrote that Toy Story 3 has a religious dimension. Emotionally it holds up for you in your mortality the prospect of having a renewed life. (Granted, it is a bit theologically unorthodox in having Woody and his brethren trade one god for another, but this is what you get when your religion is rooted in consumerism.) And while it is selling you nothing more than a lovely illusion, as you start to think about it the unlikelihood of the sentient toys' deliverance inevitably leads you to think of the unlikelihood of your own.

What The Illusionist has to offer you is not even acceptance but acceptance's ugly sister resignation, and acceptance is kind of a homely old girl herself. In life you have one spring and one summer, and before you know it all you have left to you is winter, and the only alternative to it is dying in autumn. In bittersweet sweet is always the junior partner. I think it was something of a tactical error to model the title character after Tati, as that and the constant winking references to Tati (the character bears Tati's full last name Tatischeff, and at one point wanders into a theater showing one of Tati's movies) tend to take you out of the story. It must be said however that The Illusionist comes far closer to giving us another Jacques Tati movie than any live action imitation would ever be. Of Tati himself I would say that he would have been a greater film comedian if he had made more films. Of course, his movies are exactly as good as they are, but the comedians of the silent era who are his peers were all far more productive. You could say that the only fair comparison is with Chaplin, who like Tati did everything, but a movie Chaplin took three to five years to make was a lot better than the movies Tati took three to five years to make. Perhaps this thinness of oeuvre was simply a reflection of Tati's roots in variety, since a variety performer would tour on the same piece of material for years without breaking in something new.

The most positive outcome of The Illusionist may be in the development of Chomet's art. The Triplets of Belleville had a grand satirical sweep that The Illusionist lacks but didn't quite engage emotionally. Now that Chomet has learned how to engage emotionally you can only wish that he'll find a way to bring the two together.

Last year's animation had one last pleasant surprise in Disney's Tangled. Over the last fifteen years Disney feature animation has forged a strong identity, but unfortunately that identity is irrelevance. Therefore I sat down to Tangled with some apprehension and soon began to wonder if I'd walk out before it was over. Hardly had the nine trailers for forgettable family films been forgotten when I found myself trapped in a theater with ghastly contemporary Broadway-style show music. Much as a woman forgets the pain of childbirth, I had forgotten how excruciatingly syrupy the music of Alan Menken is. Normally you are protected from this sort of thing by a laudable pay wall. It's as if you had to pay $100 to get the flu. God knows there's no situation outside of a theater where anyone would listen to this kind of music. (Quick, what's the big hit song from Wicked everyone's whistling these days? And that's supposed to be good. Not that I would dare find out.) Then, just as I was thinking of that ten dollars as a sunk cost, a comedy breaks out and all was well. It's not that the movie transcends or even avoids the clichés of the Disney fairy tale musical. The hero is the same Tom Cruise-like character he's been since Aladdin. The villain is more unpleasant than anything. The comic tough guys have the same scars and sneers and eye patches that they've had for generations. The only upgrade really is that the heroine is not the passive figure the Disney Princess normally is. It works because the clichés are brought off with panache and because along with the bad music Menken and the ghost of Howard Ashman also bring from the Broadway an overwhelming romanticism.

It remains to be seen what the success of Tangled will do to the wise resolution Disney announced before its release to swear off fairy tales. The idea that the fairy tale is central to the Disney animated feature is a self-imposed misconception that stems from the success of Snow White to begin with and the circumstance that seemed to come to the studio's financial rescue in the past, first with Cinderella, then The Little Mermaid, and maybe now with Tangled. In reality the staple source of Disney animated features has not been ancient tales from the public domain but literary properties which mostly go back no farther than the 19th century, and were mostly fairly contemporary. This is a category that includes Pinocchio.

You have to wonder how long we'll have to wait for another year of animated features as good as 2010. Sylvain Chomet and Henry Selick will be in reloading mode for some time, Hayao Miyazaki hasn't made a completely satisfactory movie since his masterpiece Spirited Away, and Brad Bird is out of the picture for the foreseeable future. The slate for 2011 is mostly a long line of sequels. A good movie could be made from Winnie the Pooh but whether Disney has done that is anyone's guess. What was hoped at one time was that computerized animation would bring the cost down to the point where risk and experimentation would become practical. What happened instead was that animated features became a big budget big business with all the risk aversion that entails. On the other hand, it seems unlikely that a Chomet or a Selick would have gotten the opportunity to make full scale animated features if it hadn't become big business.

Disney's invincible domination of animation in the '30s and '40s had a curiously salubrious effect on the medium as a whole. On the one hand everyone else had to strive for something like Disney's standard of excellence to compete, and on the other hand Disney's invincibility in its chosen field of the beautiful and wholesome led the other animation studios to counter with irreverence and bawdiness. That no one dared to compete in animated features — kind of a fool's errand even for Disney — mattered not at all because the theatrical short really was where the greatest artistic heights were reached, being profitable enough to engage the best talent in sufficient numbers and economical enough to take chances. Unfortunately the effect of Pixar's artistic domination in the present day has been for other animation studios to leave artistic ambition to Pixar. In this atmosphere the only big player with a real ambition for the heights, fumbling or feckless as they might be, is Disney.