VISION PROBLEMS

RODMAN: I forgot to ask. Do you live in a rural area? I get the sense that you're a bit cut of from the rat race.

COLAN: I'm in Manchester [Center, Vt.].

RODMAN: Yeah, but we don't know where that is. It's a place with cows?

COLAN: Plenty of country out here. Plenty. The medical help here, you could die. [Laughter.] It's not the place to live if you have medical issues.

RODMAN: How have you been doing?

COLANE: Fine. I have to go up for another operation. It's not going to be a big one.

RODMAN: I’ve had relatives who have had to go in for that cataract thing.

COLAN: I’ve had that too.

RODMAN: It’s a major trial. And I can imagine for you as an artist it’s particularly scary.

COLAN: I have to go off to Boston. Then I may have to go off for just a few days, and I may have to go off again [in mid-September and again in mid- October]. After the operation, I need looking after. And then after that, I have another operation. That's the price to pay when you have glaucoma. At least I can see.

RODMAN: Yeah, thank God for that. It sounds like you just said you have three more operations. Is that correct? Or is one of them a follow-up?

COLAN: One of them's an operation that they have to follow up on and make sure everything’s all right. [They need to] see what the pressure levels are; see if they can't maintain that pressure. Everybody has certain readings; my eye pressures can’t be much above ten.

RODMAN: That’s the thing about having a chronic medical conditions. You have to learn enough about the science of it all so you can discuss it with anyone, on demand. I don’t really know the standards for normalcy, but I know a little about eye pressure.

COLAN: Some people can tolerate a lot more than that – 15, 16, 19. And I had glaucoma. Usually, that’s an indication, that if have high pressures like that then you have it. You don’t even realize it until they take a pressure test. And at that point they discover just what’s what. That’s what happened to me, like 25 years ago, and I’ve been dealing with it ever sense.

RODMAN: And you have another procedure coming up later?

COLAN: The other eye. They can’t do them together. It takes separate times. I have to do it. Anyone that knows me knows that I’m involved with this. It’s gone on for quite a while now. Without that, I don’t know where I’d be. I’d be reading braille. I use my real good eye, the one I work with all the time, it’s the right eye. That’s in great condition.

RODMAN: And your vision is good right at the center, close up, but it's the peripheral vision that's the problem?

COLAN: Then I don't see. If anybody comes up to me on the left, I can't see it at all until they're past me.

RODMAN: Luckily, it's a very selective problem in that it allows you to work.

COLAN: Well, you know, I'm only a few inches from the board.

MOVIES

COLAN: Dom Deluise lives just a short distance from here. I met him in a restaurant just the other night. He’s a very sweet guy. He talks to you as if he’s known you all his life. So friendly and outgoing. He says, “By the way what’s your phone number?” Can you imagine that? [Laughs.]

RODMAN: Well you found him in a restaurant. He was going to be in a good mood!

COLAN: He was in the restaurant with two other people. And I waved to him, a wave of recognition, and he said to me, “Come on over, come on over!” So I went over to the table, and he asked me what I did for a living. So I told him. And he said “Oh my God,” he said. “Oh, my God” [Laughter]!

RODMAN: Well, you’re a celebrity – of a kind – too!

COLAN: Because you know, he’s an entertainer. So, one thing led to another and he asked, “What’s your phone number?” So, I gave it to him. I said, “What’s yours?” He gave it to me!

RODMAN: We’ve been touching on movies a lot. The discussion comes back to them repeatedly. I know you’ve got a particular affection for Westerns.

COLAN: Oh, I love the Westerns. Like all kids, I was attracted to a Western. There were some really hard stories connected with the western. It became quite sophisticated. Hollywood has grown up since, too. I've seen a lot of Westerns – but they were serious attempts at telling a decent story.

RODMAN: Is your attraction to the romance of the period, or the "morality play" aspect of certain films? With decency under stress, or attack, like in High Noon?

COLAN: Gary Cooper was always my idol as a youngster. I loved everything he ever played in and just the type of man he was. When I was about thirteen, I travelled once to California with my folks; that was a nice experience. Los Angeles, and through there. That was a great time for film, I even got to see Gary Cooper’s house. This was sometime in the early 1940s.

RODMAN: You’ve had plenty of chances to visualize the genre, all though the 1950s with titles like [DC’s] Hopalong Cassidy.

COLAN: No, not so much Hopalong Cassidy. That just happened to come along. More of the serious [black and white era] Westerns like My Darling Clementine. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that one.

RODMAN: Yes, with Henry Fonda.

COLAN: Henry Fonda, right. Shane. Although Shane was in color. My Darling Clementine was in black and white. Any film that has some mystery to it, and some action. Hopalong Cassidy was, you know, like a grade-B movie.

RODMAN: They took the mythology of the Western and went into some very adult area. Hopalong – the movies, not your job in the comics – was just for fun, then. All the drama. We’ve mostly been discussing the older black-and-white stuff. I know you’re constantly watching newer things in your home theater. Can you just tell me about some of the contemporary things that you like?

COLAN: [I like] Scorsese's work a lot. He's made some films that weren't as great as the others, but he did Mean Streets, and he did Cape Fear. I thought Cape Fear was great. My wife and I had seen that end and I was very taken by it. By the angles, you know, the lighting, and all that stuff, that was a good movie. And he directed it beautifully. He’s done other good things, but I think he eventually just got swallowed up by Hollywood itself and he lost his own voice in it. He repeats himself a lot in film. But he's best when he's dealing with gangster types of film backdrops, the gambling Vegas lifestyle – he really shines.

RODMAN: Do you mean Casino?

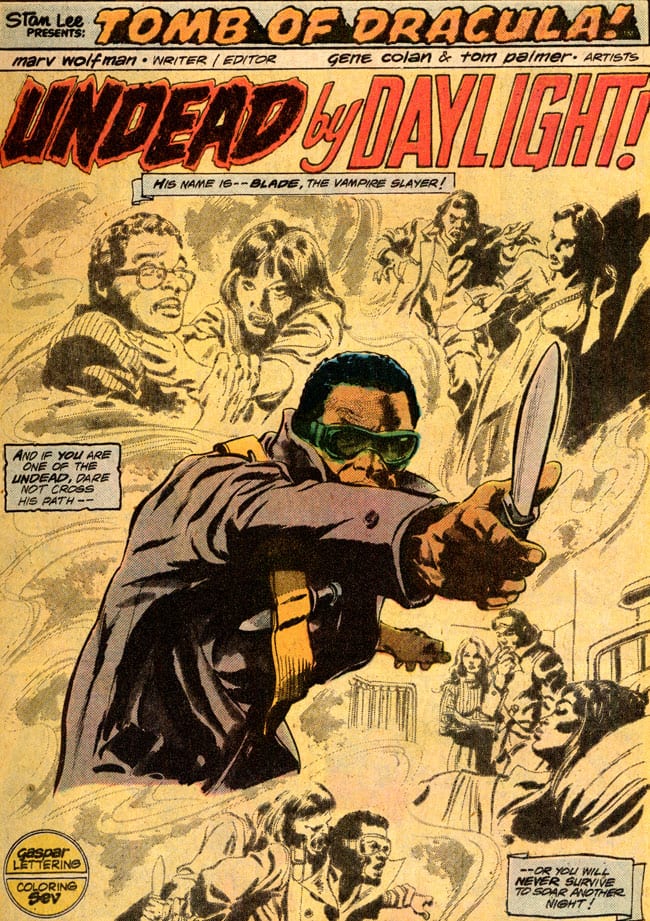

COLAN: I didn’t care for it. It’s all Hollywood that’s why I didn’t like it. Sharon Stone was in it. Comics now and movies they all dovetail. You know they made the film Blade? The characters were all created by Marv Wolfman. They just simply listed us.

RODMAN: I rented that movie. The style, the way they visualize that whole world, it's much grosser than your approach with Wolfman – which got pretty extreme in itself brutal ways had more to do with plotting and characterization than gross-outs. There was violence and wickedness a plenty in your comics, but still … You've always been careful to build on mood and atmosphere in your work.

COLAN: You wouldn't want your children to see it [the movie. They're going to put out another one [a Blade sequel]. We're the ones that created the character. We're not getting a dime out of it. He's [Wolfman's] suing them. I didn't want to get involved. Once you get involved in lawsuits and lawyers you know, you're up to your neck and you're spending your life savings.

RODMAN: To be blunt, with your treatment by the Marvel Entertainment Group, and all the other various shenanigans over the years, you've gotten screwed a number of times.

COLAN: Oh, and how! And with our eyes open.

RODMAN: I’m not terribly surprised to learn that you've got a jaundiced view of the industry. It's rotten to hear some of the stuff that's happened to you.

COLAN: It happened to Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. But the fans saved their neck, to some degree at least. They [DC] were ashamed of themselves, and they didn't know where to go with it. And they felt in order to stay in business, they had to damn well cough up a little of the profits to the originators. So, that's what they did. But not a hell of a lot.

RODMAN: Well, every now and then, things work out. You just have to be crazy enough to buck the system.

COLAN: Yeah. [Laughter.] Sometimes you just have to do it. Buck the system in order to get some justice done.

RODMAN: It 's always surprised me – being a naïve soul – how the industry has based its entire mythology on heroism and virtuous behavior; the best traits of humanity. But the daily reality was about the creative people being screwed left and right.

COLAN: It's a shame what's happened to the whole world, in general.

RODMAN: In other words, everything’s been blown up in a commercial sense, for a quick buck. Some of the feeling is lost.

COLAN: It's all money. The whole thing.

RODMAN: It's what happens when parts of the culture have disappeared and begin to be missed. You look around nowadays and you say, “What the hell happened?” For example, there's no more radio drama, which I know is something you were particularly fond of.

COLAN: I loved the dramatizations of Suspense, The Lux Radio Hour. You ever hear of any of these? The FBI At War. I had to buy some of these programs on tape. It's almost a lost culture now. They had to bring it back. The radio has changed so radically. You know, things change. Even you. You think you're standing still but you're not. It's interesting, when age creeps in, how your career begins to fall apart.

RODMAN: A lot of comics artist have gone over to film or have spent part of their careers in film or animation. I know you’ve done projects in storyboard and film design.

COLAN: I did a little bit on a film called The Ambulance. Originally, it was called Into Thin Air. It was with Eric Roberts and - I can't remember his name; the black actor who played Darth Vader – James Earl Jones. Eric Roberts played the part of an artist. He can't draw so when ever they needed to shoot him drawing he could fake it, and I would actually do the drawing. I got to meet the cast. It was a wonderful experience. That was a good number of years ago. Right now, I have a huge project coming up. It's called The Spider, the original pulp [character]. It's for someone that's sold the idea to a film company, and he wanted to present an episode in full-blown drawing.

RODMAN: So, it's more than a storyboard, and more like a comics narrative. Is it to help sell the film, or is it more of a public-relation presentation?

COLAN: He tells me he has it [the financing] pretty much wrapped up, but he needs that extra boost. Right now with communications the way it is, you get to know so many different people. I don't think I'd ever dream of doing anything for film, and yet I've had an opportunity to do it. I guess because of television, and all the new video inventions that have come out, and the telephone have all made this world a very small place. I have a nice following. People who write me on e-mail. The opportunity of meeting some of these people is far greater now than it's ever been.

RODMAN: I've spoken to other comics industry veterans who feel the same way. You impress me as having considered the work more than just a job, although it was still regarded as a disposable medium, something no one was going to care about after six months time.

COLAN: You never think of these things. In fact, we weren't allowed to sign our names at that time, and no one ever thought it would come to anything. Look what's happened.

RODMAN: And we're definitely past the time when you necessarily had to live in a media-intensive city to been gaged in the field There's such a concentration of media and entertainment industry activity, now. You've adapted to the times with your website, to use just one example. Assignments come to you, but you must still be doing something to seek them out.

COLAN: At one time the only form of entertainment was to go to the neighborhood movie house. We didn’t have television. I mean, you had the radio. But there was not much else in the way of entertainment. Most people went to the neighborhood theater. And to them, that was a very special place to be because you felt that you had died and gone to heaven when you went to a movie house. They were palaces then. Even the smallest movie houses had beautiful decor; they were absolutely fantastic. You could spend a few hours in the theater, and get away from your troubles and worries. It was a great place to be. You couldn't find that anywhere else. The closest you could come to it would be the radio. But things have changed drastically. You can bring any film into your home now. Not in film form, but you can get in on video, on DVD, and God only knows what the next 20 years is going to bring. It will be one heck of a world. It 's an adventure. I don't even venture to think where we're going to be at that time. Virtual reality – they're working on that. Taking you to a place that you swear you were at and you haven't left your room at all. All kinds of wonderful things are going to happen. So, we're living in a world where you can reach people very easily, and get to know people that you never knew before. And that's wonderful. I think that's great. Yet the world is smaller and smaller and getting very difficult to live in. Too many things are happening. Not all of them good.

SVA& ART THEORY

RODMAN: I ran across reference that you taught at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan.

COLAN: Yes. And there was another school there, the Fashion Institute of Technology. FIT. I taught there. I taught a course on comics.

RODMAN: When exactly was that?

COLAN: The 1980s. Late '80s. At the same time I was teaching at the School of Visual Arts.

RODMAN: I would say you probably had quite a bit to pass on to people.

COLAN: Well, I would try. Teaching is an art unto itself. It's very difficult to explain just how to go about it; being a comic-book artist. The feeling, and a step by step process. Although there is a process that you go through, and you try to explain it to the students what you went through. Some of the mare very impatient. Sometimes I've had some trouble with students; not very much, but occasionally they clown around in class. I just throw them out! That's OK. There's very few of those. After a while, I found it so difficult to teach the class, I just eventually drifted from it and just stopped doing it altogether.

RODMAN: Well, it takes quite a bit out of you.

COLAN: Yeah. In my case, I was traveling. When I lived in New York it wasn't any trouble, because I'd just get on the subway and get downtown to where the school was. There was no trouble because I lived right in Manhattan. But I did it from here for a few years. From Vermont. I used to commute.

RODMAN: When did you leave New York?

COLAN: About 1990. Around there.1991, in that area.

RODMAN: I've been teaching art to middle-school level student for a while, and everyone seems to understand the idea of drawing or painting the single image, but doing cartoons – with continuity, or different panels in a sequence that's a totally different concept.

COLAN: Right. It's very different. Very hard.

RODMAN: It would come more naturally to someone who's been reading the comics in the paper all their lives, I guess.

COLAN: No, it comes from the movies, as far as I'm concerned. That's how I learned continuity.

RODMAN: A step by step process that leads some where as a narrative story …

COLAN: Yes. You have to pay attention. You know, there's a beginning to everything. If somebody is going to enter a room, he has to first approach the room. There are certain movements that take place. Like in animation. You have to follow through with action. It's very hard to teach, unless they [already] have an inkling of what I was talking about.

RODMAN: I know what will connect to students. Whatever they respond to, you have to go with that, as opposed to whatever you came in with.

COLAN: Right. [You might reach] two out of the class. Sometimes there were 10 in the class, sometimes less. If I could connect with one student, or with two at the most, you're doing pretty good. [Laughter] They were all very impatient. They wanted to know all the stuff right away.

RODMAN: Well it's rough. Because the sort of drawing you do is very time-consuming.

COLAN: Yes. I try to teach them just the idea of how to tell a story. Then I will give the man example, actually have them makeup a story In five or six panels, or in two pages. Have them makeup something. Anything. Sometimes I just give them a title to something, and see what they can do from that. See what ingenuity they had, what ability to turn a title into a project. I would leave it up to them as to what they got out of it. And then I would tell them a story sometimes, and have them illustrate it. But, I would have them come up with something totally original, if I could. I would tell them a story; it could be a war story, it could be a scary little thing, and see how they do. Usually they would come up with things that weren't so interesting. They were just beginning to get their feet wet trying to find out how to go about this business of being a comic-book artist, which is very difficult. It takes practice, and devotion to it; this is what I've told them at the beginning of every class. You need to be devoted to it. Literally married to it. And you have to do it all the time, and think along those lines. Not only that, you need to love it.

RODMAN: God, yeah, considering how much effort goes into it.

COLAN: Yeah, there's a lot of effort to it, but you need to love what you do. I try to tell them that, but, you know. [There are some] very talented students.

RODMAN: I think, as a young person, you might have to over come your own ego somewhat to be able to devote yourself to something like that.

COLAN: And so much of it is the sense of things. And that's hard to explain. I would tell them this, I would say, you know, with things in life, very often it's the sense of something. If you’re driving down a narrow street in a car and somebody's double-parked. Well, you can either pass that double-parked car – squeeze by and proceed up the street, and hope that you don't scrape your car along side of his – or you can stop and wait ‘til the driver comes out and drives away You have to judge. If you decide to pass the car, you can't get out and look at every movement as you advance to see if you're going to hit the car, you're [either] too close, or not. You just have to sense that you're not.

RODMAN: Intuition.

COLAN: Right. I guess it's like what a pilot has to do. It's more than likely automatic, but in many instances it isn't, [like] when a pilot has to know when to level out to make a landing. Are his wheels about to touch the ground? You know? It’s a certain feeling that you get. Here’s an interesting thing. If you hold the paint-brush when you’re inking your own work, if you hold it in a certain way you instinctively know whether you’re going to get a nice sharp line when you stroke the paper – or a double line, or three lines, or a flat line – something far from what you’re looking for. It’s the way if eels in the hand. Maybe the way the brush looks, and at the right point between your thumb and index finger. How does it feel? Are you going to get that line or not? It comes from doing is so often that you do get a sense of what I mean, somewhere down the line, if they stay with it long enough. If you like the movies, if you love telling stories, if you love illustrating stories, then it shouldn’t be such a difficult task. It turns out to be difficult …

RODMAN: But, you’ve already gotten yourself deeply involved by that time.

COLAN: … I think that you would rather do it than eat. It becomes a real love affair.