Tezuka was no angel. But nor were his peers gentlemen.

It did not sit well with elder Tokyo cartoonists that this bourgeois whippersnapper from Osaka was doing so much better than they were. That many of them had drawing careers extending back to the late 30s, sometimes as cartoonists but more often as animators, didn’t help. Nor did the fact that they liked to drink and argue. Ushio Sōji, who is named by Tezuka as one of the practitioners of “new expressions,” remembers parties in which Tezuka was teased as “zeiroku,” a derogatory name used by Edoites for money-hungry Osaka merchants. After a fusillade of abuse, he was also, as the industry’s top-grossing artist, often pressured to pay an entire night’s bill.

Tezuka recounts a particularly ugly episode in his autobiography. “One night, as usual a fight began. Fukui Ei’ichi, with his bright red face took me by the lapels. ‘Hey, Osaka,’ he said, ‘what’s the idea making so much money?’ A bit taken aback, I replied, ‘What’s wrong with making money?’ ‘Talent’s not all about making money y’know. The kids. How about caring some about the kids?’ ‘Are you saying my comics are bad for kids?’ ‘Yeah, Osaka, I think money’s the only reason you make comics!” Tezuka had heard rumors of people thinking such things about him. Similarly he recalled the popular journalist Ōya Shōichi tweaking the term “kakyō” (overseas Chinese) to label him “hankyō” (overseas Osaka-ite), implying that Tezuka had come to Tokyo only to mine it for money to send back to Osaka. “But there was a reason I was saving money,” explained Tezuka many years later. “I wanted to establish a studio to make animation.” Fukui’s attack was apparently the first time anyone had insulted him on this count to his face.

There was thus, in Tezuka’s defense, a personal context for the anti-Fukui page in Manga Classroom, which was published amidst exchanges of this unpleasant sort. However, it’s one thing to razz some privately, and quite another to do so in print, not only in full view of the fans, but moreover in a context like Manga Shōnen where aspiring cartoonists hung on to Tezuka’s every word.

Fukui did not take the jibe in Manga Classroom lightly. It chafed him so badly that he marched to the home of Baba Noboru, a good friend of Tezuka’s, and yanked the cartoonist out of his house in the winter rain to go and confront the cheeky Osaka-ite where he was working at Shōnen Gahō’s offices. Giant by Japanese standards at 80 kg and 175 cm, Fukui barged through the publisher’s door and demanded an apology for the insult, under threat of a thorough throttling outside. Baba intervened by suggesting that they talk things through over niku-dofu (meat and tofu stew) in Ikebukuro. Confronted with the evidence, Tezuka tried to explain, “That wasn’t your work I was referring to. That manga was just made up,” which was a patent lie. Fukui grew more enraged. It was all too obvious whose work Tezuka had cited. Cornered, Tezuka was finally forced to admit the truth and apologize. “I searched in my heart like coward for a way out of the situation,” he recalled in his autobiography. “Truth be told, at the time I was extremely jealous of Fukui’s drawing. That ended up bleeding unconsciously into Manga Classroom in the form of slander against an Igaguri kun-like manga.”

Unconsciously? He names Fukui outright on the previous page.

Tezuka’s attempt at an apology did not end in Ikebukuro. It continued in the follow-up installment of Manga Classroom – where we get to see how Tezuka was never intent on taking full responsibility. In the introductory title block of the series, Professor Anything and Everything usually looks happy. This time he winces from being hit over the head with a pen.

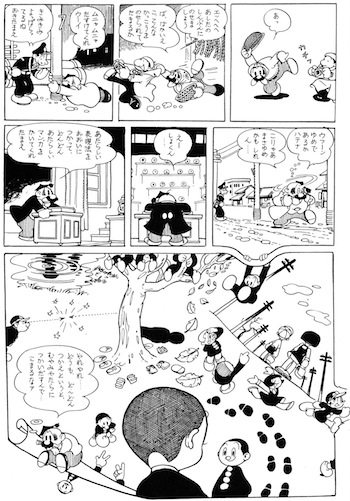

The Professor begins by rereading the closing remarks of his last lesson, where he explains how these “new modes of expression” are an expedient for artists under deadline. Two panels later, he is waylaid in the street by two shadowy figures carrying giant pens. “B-b-but I don’t have any money on me,” the Professor splutters preemptively. “We’re not thugs, we’re cartoonists. We’ve come to tie you up,” says one. “B-b-but have I done something to offend you?” “Yeah, your lecture today offended us . . . you said that cartoonists are dishonest and lazy . . . but we ain’t drawing like that for kicks. It’s all carefully calculated to produce expressions with the greatest appeal.” Though the figure’s faces are in shadow, anyone familiar with this era of manga will quickly identify the pair from their clothing and silhouettes: Fukui and Baba Noboru. They tie the Professor up by his neck and drag him off to teach him what’s to be gained from “new forms of expression.”

On the next page, three comparisons are presented to the Professor for consideration. The first shows a rabbit praying to the moon that his mother might recover from her illness. The first panel is in that flat view which is often called “stage set style,” while the second is dramatized through shadows, immersive perspective, and a tilted plane.

The second comparison, conducted appropriately by Fukui, shows a judo toss. One has the body thrown toward the viewer, creating depth within the panel. In the other, tossed and tosser are on the same plane.

The last comparison shows a Rock Home-type boy detective spotting on the street some precious pearl-like jewel. The correctly dramatic panel features a close-up of his hand framed by radiating visual FX that expresses the surprise of discovery.

The two shadowy cartoonists conclude, “See? If it’s artistically effective, then there is no problem with a picture being simple.” The Professor concedes and is made to dance as an ass in punishment – which makes one wonder what other forms of hazing young cartoonists experienced during night outings. The next day, a hung-over Professor stands before his class and says, with palpable hesitation, “So, uh, kids . . . make sure you use lots of new forms of expression and create new types of comics.” Sounds nice. But what does the last panel show? Chaos: too many visual gimmicks crammed one next to another. “Oof, I said use lots of them,” says the exhausted Professor in closing, “not go crazy with them.”

Apologetic Tezuka might have been, but in the last instance “new expressions” could only mean an anti-cartooning tableau. Sorry for having offended you, he is saying, but I meant what I said.

(cont'd)