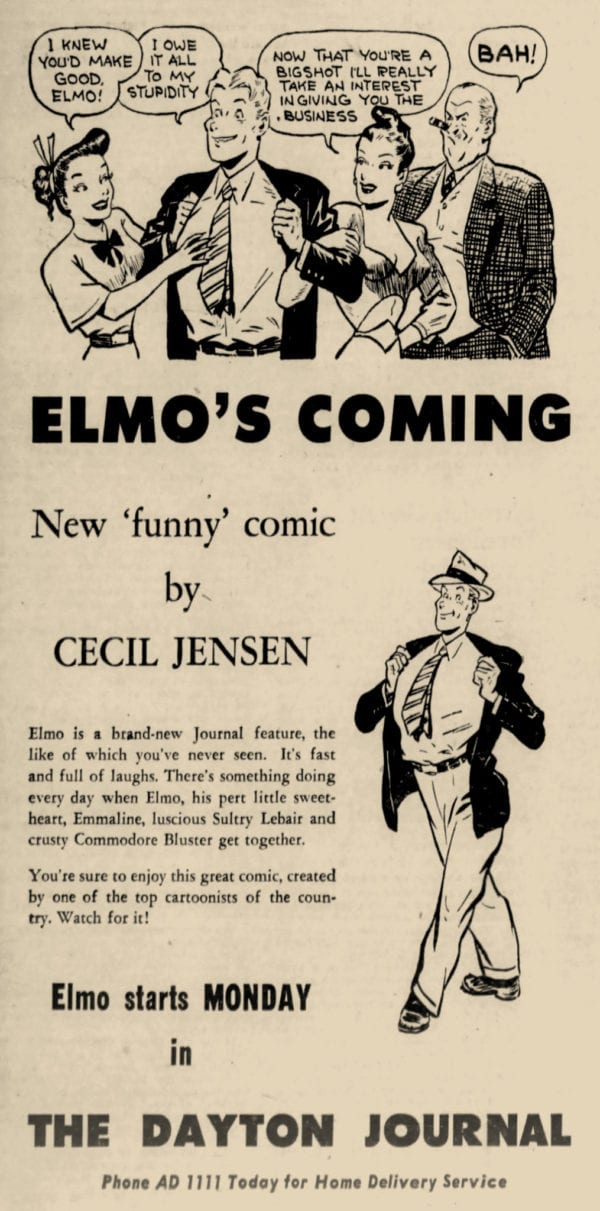

Elmo Chuckle, 1948 (left) and his creator, Cecil Jensen c. 1950

Elmo Chuckle, 1948 (left) and his creator, Cecil Jensen c. 1950

The year 1946 in America was a bewildering blur of emotions and sensations. The war remained a vivid experience that the nation hoped to put behind itself. To forget it wasn’t possible. Shortages remained, demand exceeded supply, and a generation of battle-hardened vets did their best to adjust to a life without constant murder and mayhem.

There wasn’t much to laugh about, although mainstream media begged to differ. During the war, American comedy became brassy, bawdy, and aggressive. It was the perfect time to be a Betty Hutton, Tex Avery, or Danny Kaye—wild was in, and anything that could take the national mind off its steady diet of worry was welcomed. Mass media had to directly address the war while being a jazzy diversion. Its value as a propaganda and educational tool was never higher. From lofty literature to the comics in culture’s gutter, creators couldn’t not talk about the global madness the Allied Forces were fighting to keep at bay.

Imagine waking up on an average day in the fall of 1946. You’ve been through hell—even if you never left your hometown, and did no military service, the war impacted you in some meaningful way. You did without a lot of everyday things—coffee, cars, meat, sugar—so those materials could go toward the war efforts. The hoped-for paradise of a warless world was just a dream. If you were looking for a place to live, a new car, or a sirloin steak, you faced stiff competition. No longer could the simple things of daily life be taken for granted. And things were far worse in Europe. The world was at Ground Zero. The anxieties of the Cold War were already present. The threat of nuclear extermination was a reality. Communism replaced the Axis as the Big Evil America always seems to require in order to function.

This impasse was felt in the comics. No more references to rationing, food hoarders, or tire thieves. Shades of khaki and olive drab diminished in the Sunday strips. The characters who’d survived the war picked up the pieces of their life before Pearl Harbor and tried to soldier on. Buz Sawyer seemed at odds with civilian life after his harrowing war experiences. Skeezix Wallet returned to start a small business in Gasoline Alley. Nancy could no longer do Hitler, Mussolini, or Tojo gags, although Joe Stalin (and, later, Nikita Kruschev) was still ripe for a topical titter.

New comic strips popped up—some by returning veterans. The first hard-boiled private eye on the funnies page, Vic Flint, tough-talked his way into mass circulation, and wartime cartooning phenoms Dave Breger and George (Sad Sack) Baker brought their GI dogface characters into civilian life. Alex Raymond’s intellectual sleuth Rip Kirby debuted alongside nature-loving Mark Trail, while Milton Caniff left Terry and the Pirates behind (at year’s end) to develop his second strip, Steve Canyon. And Elmo wandered onto the newspaper page.

His stay was a quickie compared to these other features: he was outta there before 1948 ended. Elmo never quite caught on. It was ahead of its time and behind the times—a strip with the absurd cool of a Nathanael West or S. J. Perelman and droll ensemble comedy reminiscent of E.C. Segar’s Thimble Theater. Its star was a Cold War Candide—a can-do cipher to whom crazy things happened, and which he took in stride, a mindless grin on his boy-next-door puss.

Elmo was Cecil Jensen’s third newspaper strip in a career of two decades. What compelled Jensen, a prominent political cartoonist with a home base at the Chicago Daily News, to add a daily strip to his regime is lost to time. Elmo (renamed Elmo and Debbie in December 1948, after Elmo was AWOL, then Debbie in early ‘49, with its final title Little Debbie as of 4/3/1949) was a venue for a personal agenda and comedic vision.

The strip’s inspiration, at inception, appears to have been Al Capp’s frantic, satirical Li’l Abner, and by the Horatio Alger rags-to-riches school of fiction—a ripe target for satire in the comics. We lack an account of the creator’s motivation, so we can guess and hope we’re remotely right. Cecil Jensen played his cards so close to his vest they might as well have been in his coat pocket. He never seems to have discussed Elmo at all.

Radio comedy cast a long shadow over American popular culture in the 1930s and ‘40s. Much of the humor in the Warner Brothers cartoons is built off catchphrases, situations, and characters cribbed from such shows as Fibber McGee and Molly, The Great Gildersleeve, and The Jack Benny Show. Animation historian Devon Baxter did an illuminating series on radio’s influence on animation. The first in his series of columns is here.

Radio comedies overflowed with king-size egomaniacs. Their broad strokes and me-first attitude were comedy gold for the brassy 1940s. Jensen, like the Warner Brothers cartoon-makers, might have had one ear to his radio while he worked on his cartoons.

The comedic vision of W. C. Fields is another likely source of Elmo’s inspiration. Fields favored blowhards, cranks and nincompoops as foils for his bemused, cynical everyman. In his most personal and accomplished films (It’s a Gift, The Old Fashioned Way, The Bank Dick) one can see precedents for Jensen's favored character types. Fields' fondness for unusual names is seen in Elmo's supporting players, whose quirky monikers anticipate similar use by Bob Elliot and Ray Goulding in their radio and TV comedy of the 1950s.

Elmo might have made a successful radio comedy. As a comic strip, it was an anomaly in the post-war market. Recognizable reality appealed to newspaper readers. The wildest of the top narrative strips (Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, Buz Sawyer) kept their feet on just enough terra firma to make their darkest moments palatable. Mundane domestic dramas and comedies like Mary Worth, Blondie, Judge Parker, Rex Morgan MD, Penny, Jane Arden and Joe Palooka dominated the market. A mild conflict or a kick in the keister from the boss was as hot as these mundane strips got.

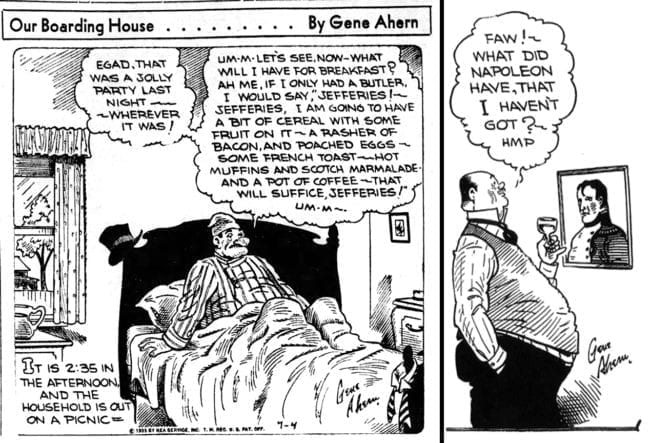

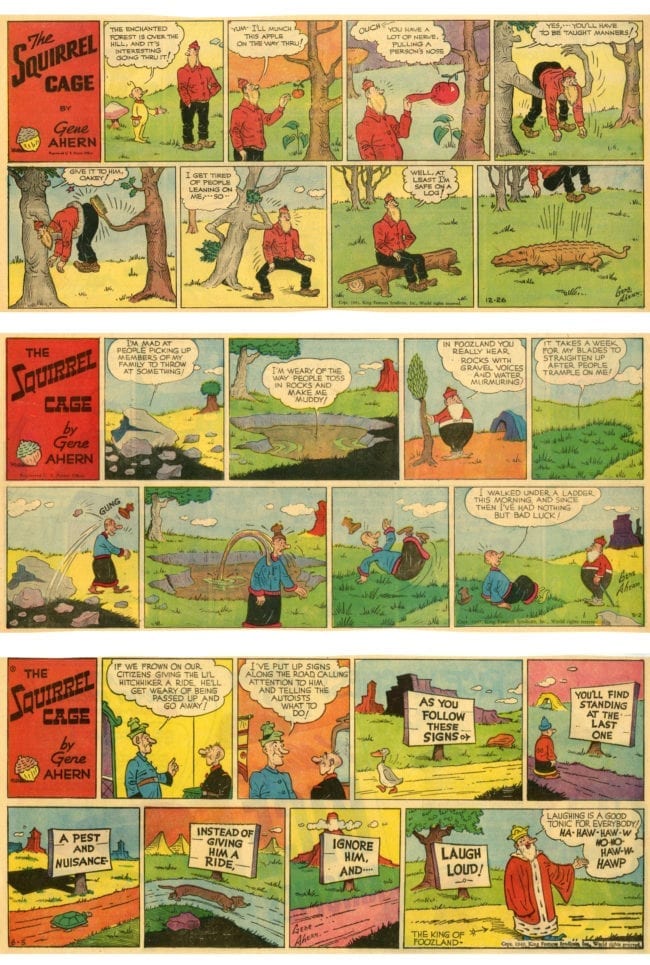

The only comic strip that approached Jensen’s comedic vision had been around for a decade when Elmo debuted. Gene Ahern’s The Squirrel Cage launched in 1936 as the companion strip to his self-imitative but highly amusing Room and Board. Ahern’s worldview intersects with Jensen’s. Both are hard worlds where insults and brickbats harangue those who dare to be different. The grand gascon Amos Hoople, of Ahern’s prior Our Boarding House, and Judge Puffle, the irredeemable rascal who was Room’s focus figure, might have been a friend (or distant relation) to Elmo’s Commodore Bluster. Both artists populate their worlds with shrill harridans, sneering wise-guys, and amiable dimwits.

The Squirrel Cage is a huge and highly personal flight of fantasy. Having lured the artist away from Newspaper Enterprise Association in 1936, King Features Syndicate seems to have granted Ahern Squirrel Cage as a private playground. The strip’s enigmatic bearded hitchhiker, an obvious visual forefather of Robert Crumb’s Mr. Natural, caught the public fancy in the later 1930s with his mantra of “nov shmoz ka pop.” (Radio comedies excelled at making such catch-phrases viral.) At first a skewed sitcom of two irritable bachelors’ attempts to shoo the hitchhiker, Squirrel Cage morphed into a weekly trip to an addled fantasy universe where nothing is immutable.

from the collection of Carl Linich

The Sunday-only Squirrel Cage lasted into the early 1950s, tolerated by its syndicate and carried in a handful of papers. (The crowd-pleasing and highly amusing Room and Board shut its doors at the end of November 1958, when Ahern retired from cartooning. He died in March 1960.) Squirrel Cage approached wild fantasy with a blasé attitude. Casually presented were the wildest notions and images since the heyday of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo. Ahern’s psychedelic wanderers shrugged their shoulders at the surreal and went about their business.

Jensen might not have been able to articulate what he attempted in Elmo’s brief first run. He seems aware that he's up to something different. Though patterned on strips such as Li'l Abner, Elmo goes places that might have frightened other cartoonists to pursue. Each episode feels like a leap of faith. Jensen's risks pay off most of the time, but the process may have been excruciating. Elmo sits uncomfortably beside the likes of Steve Canyon, Abbie an' Slats, and Gasoline Alley—three strips that subscribing papers usually ran along with Jensen's work.

When he realized this experiment wasn’t going to pan out, he eased Elmo out of his own strip, and soldiered on with its gently jarring, inscrutable sequel, Little Debbie, into the end of September 1961. The weighty brushwork that inaugurated Elmo became broader and more free-wheeling by mid-1947. Little Debbie was no compromise—it’s very much Jensen’s vision. At first glance, the uninitiated might dismiss it as part of the post-war mass of suburban gag-a-day strips. Debbie might better be called Elmo Minus Elmo. In the forthcoming second part of this piece, we’ll take a look at what made Debbie tick.

In October 1946, when Elmo debuted via the Register and Tribune Syndicate, it was a wild novelty. The 44-year-old Jensen (he was born January 17, 1902) was a respected artist, with a backlog of acclaimed political cartoons and two prior terms as a strip cartoonist. His first published cartoon appeared on the front page of his hometown paper, the Ogden, Utah Standard-Examiner when he was a 16-year-old delivery boy for the daily.

Jensen left Ogden in the early 1920s to study at the Chicago Academy of Art. While there, he was twice interviewed by the Tribune’s man on the street reporters. According to a profile of Jensen published in 1957, the artist was colorblind. One wonders how this affected his art studies. It certainly instilled in him a different slant on the world.

At age 21, Jensen became a syndicated cartoonist. The New York-based Bell Syndicate bought his Tied for Life, a daily about a middle-aged married couple that debuted in April 1923. It followed in the footsteps of Sidney Smith’s The Gumps with a blend of humor and semi-serious narrative. Faint glimmers of Jensen’s later work peek through these tentative drawings.

The Standard-Examiner ran Tied For Life for seven months. Its debut was front-page news in Ogden. The strip abruptly ended in mid-week that October. The syndicate sold the strips twice to the Minneapolis, Minnesota Star—for a few months in 1923 and again from May to July 1927. By that time, Jensen had been in Los Angeles for three years.

In 1924, Jensen became the editorial cartoonist for the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News. Jensen’s editorial work was highly regarded by his peers from the start. His hometown paper reported with pride, at the end of 1925, that two Jensen editorial pieces were selected by The Literary Digest—a magazine that spotlighted the best American writing (and cartooning). In 1928, Jensen relocated to Chicago and began a long professional relationship with its Daily News.

Both Daily News papers remain inaccessible for online research, and leave a large swath of Jensen’s career yet unexplored. From 1928 to 1967, Jensen did daily editorial cartoons for the Chicago News, which syndicated them. One can chance upon Jensen’s editorials in various papers, but no daily seemed to consistently carry them outside of the Daily News. Among Jensen’s last widely circulated cartoons was a 1967 caricature of Lyndon B. Johnson. Technically retired, Jensen continued to turn in two editorial cartoons a week from his final home in Fayetteville, Arkansas, according to his obituary notice.

Jensen’s second comic strip, Syncopating Susie, ran in 1931. It was not syndicated, and, except for one example online, remains unseen to those without access to the microfilmed records of the News. As Jensen’s truly “lost” strip, it would be revealing to see—does it anticipate his later work, or is it tentative, derivative stuff like Tied for Life? Here's that one example, so you don't have to go searching for it:

Here are some examples of Jensen’s cartoons from the 1930s. Some of them are apolitical—their barbed social observation is more amusing than the typical labeled tableaus of the era. They’re akin to the NEA panels Out Our Way and Our Boarding House—or perhaps inspired by H. T. Webster’s droll commentaries on American life.

Jensen’s wartime cartoons show the artist thinking Elmo-ish thoughts. Below is what may be the funniest Hitler cartoon of all time, plus a warfront piece with a zany, fantastic element.

What compelled Jensen to tackle a daily and Sunday comic strip, after a long absence from the medium, is anyone’s guess. Editor and Publisher reported that Jensen had to agree to produce at least one editorial cartoon a week on top of his Elmo workload. (He did a daily editorial alongside his strip work for many years, according to a 1957 Jensen profile by Minneapolis Star-Tribune cartoonist Scott Long.)

Jensen would have known that a strip was a full-time proposition—unsparing in the time involved to write and draw it. Perhaps the notion of creating fictional characters, after all those years spent drawing global political figures, was refreshing. Jensen tucks into Elmo with a graphic fervor that anticipates the rococo drawings of Will Elder in Harvey Kurtzman’s satire comics and magazines, from Mad on.

His work also resembles a comic-book artist like Wayne Boring (a leading Superman artist in the 1950s and ‘60s) who has neglected to take his medication. The face of Elmo is drab, low-key, in contrast to what is said and done by its figures. This initial tightness slowly unwinds during 1947. By that year’s end, Elmo looks radically different than its first few months. Here is the first strip and the Elmo for October 28, 1947.

The second strip appears hastier is its execution—or, perhaps, more assured in crafting the cartoon image. Jensen’s editorial cartoons of the 1930s and ‘40s display a painterly eye in their evocation of moods, textures and contours. Elmo is initially tighter than his contemporary editorial pieces, and Jensen seems 110% invested in its deeply eccentric universe.

Elmo the character is a visual discrepancy in his own strip. Jensen's default style is a cartoony semi-realism, akin to the Canadian comic book artist Jimmy Thompson (of Robotman fame). Regular characters like Commodore Bluster and Emmaline and drawn in a straightforward manner. Elmo has an almost abstract face—squarish eyes offset by distorted cheekbones, an off-kilter nub of a nose, a mouth that looks like a door hinge and an outlandishly jutting jawline. He looks like no one else in his world. This visual otherness further removes Elmo from the role of comforting protagonist—an essential need for a daily comic strip.

Elmo's unusual face reproduced abominably in anything but close-up. As shown in the collage of unrestored newspaper panels below, Elmo's eyes are often blurry blots (with one sometimes missing). Chunks of his outlines can go missing, and his hair often looks like hell. This problem seldom arises with Jensen's other characters. On the crowded daily comics pages of most 1946/7 papers (which resemble a parking lot full of beat-up cars), Elmo stands out because it's usually the worst-printed strip.

Cecil Jensen's hometown paper did not run Elmo, or any of Jensen’s comics work after Tied For Life, but it kept track of his activities. Their casual reportage of his work and home life gives us some idea of his private and family life. (When his daughter Renee was married, the news rated a large photograph and a short but substantial article.) Had Jensen’s hometown paper run Elmo, its antics might have non-plussed the Utah locals. It was neither laff-a-day stuff or a dedicated serial.

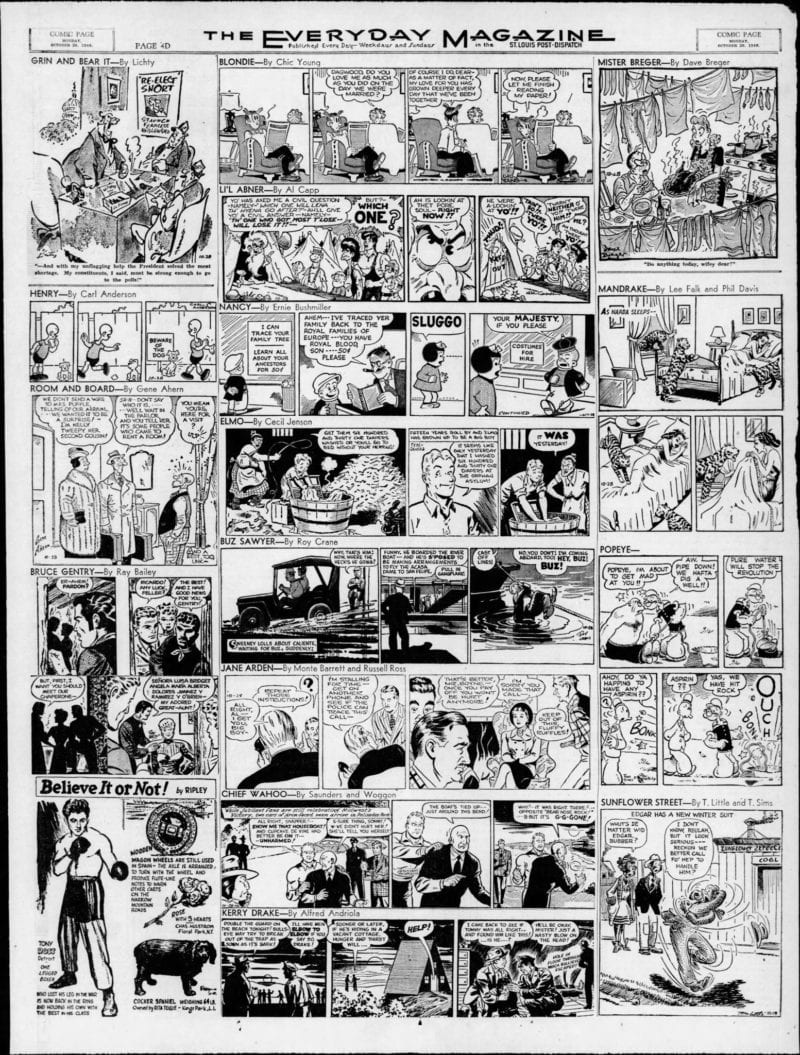

The strip’s placement on the jam-packed daily comics page of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch is ideally symbolic. Above it is Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy; below sits Roy Crane’s Buz Sawyer. Elmo has some qualities of Nancy, though it’s the graphic opposite of Bushmiller’s spare, rigid work. It spoofs the crash-bang storylines of Buz Sawyer, and the solidity of Jensen’s artwork suggests “adventure strip” before its reality sinks in. (Elmo looks like a Sheldon Mayer version of Milton Caniff ’s Steve Canyon, to further blur the issue.)

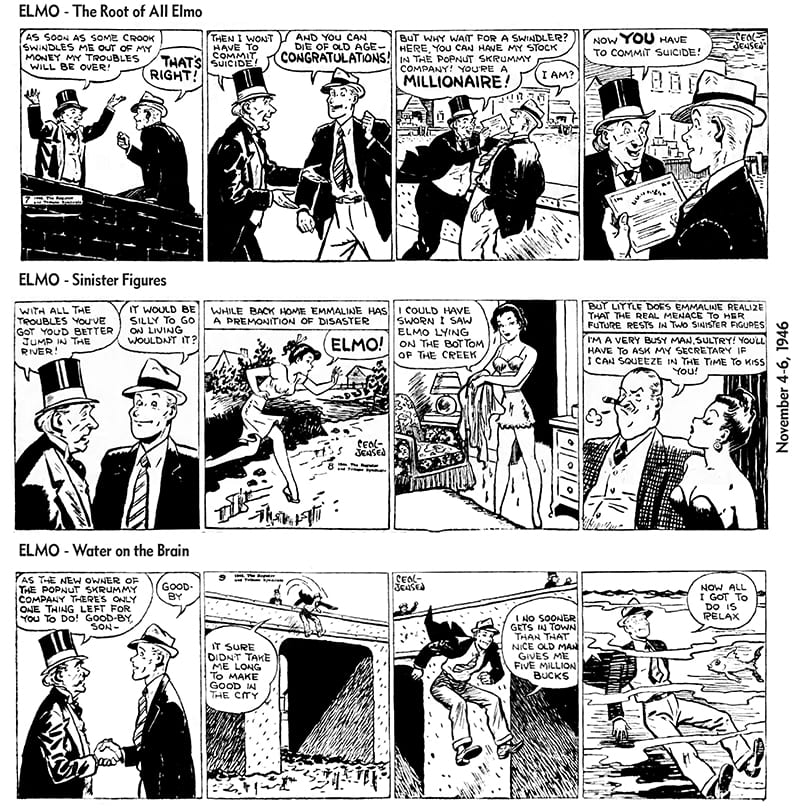

Elmo requires some set-up; here are the first two weeks of the strip, as restored by myself.

It’s a comedy concept worthy of Preston Sturges: naive goofus gains controlling interest in corrupt company; frustrates blowhard who is firm’s sinister status quo. Sturges was just coming off his string of auteur screwball comedies for Paramount Pictures as Jensen’s strip debuted. Elmo suggests a fantasy collaboration of Sturges and David Lynch. Unlike Sturges’ brassy heavies, the bad guys in Elmo are outright sociopaths. Commodore Bluster intends real harm to Elmo, whose dumb luck has put him in ownership of the Popnut Skrummies company. Jensen goes into dark places as he navigates the underbrush of his imagination.

Seldom played for direct comedy, the early months of Elmo are full of laugh-out-loud moments, props and characters. Jensen’s comedic sensibility is a slow burner. One often laughs minutes, hours or days after reading Elmo. A sublime example of Jensen’s achievement is found in the November 2, 1946 strip. The suicidal millionaire’s bleak vision of his life of luxury is a moment that will grow on you as its comedic depth bombs discharge in your head. This poker-faced approach would find public favor in the 1950s, when the comedy team of Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding brought a Sahara-dry absurdist comedy to radio and television. Bob & Ray plied their trade for decades; perhaps hearing lunacy was better for America than getting it in daily strips, crowded in beside Jane Arden and Blondie.

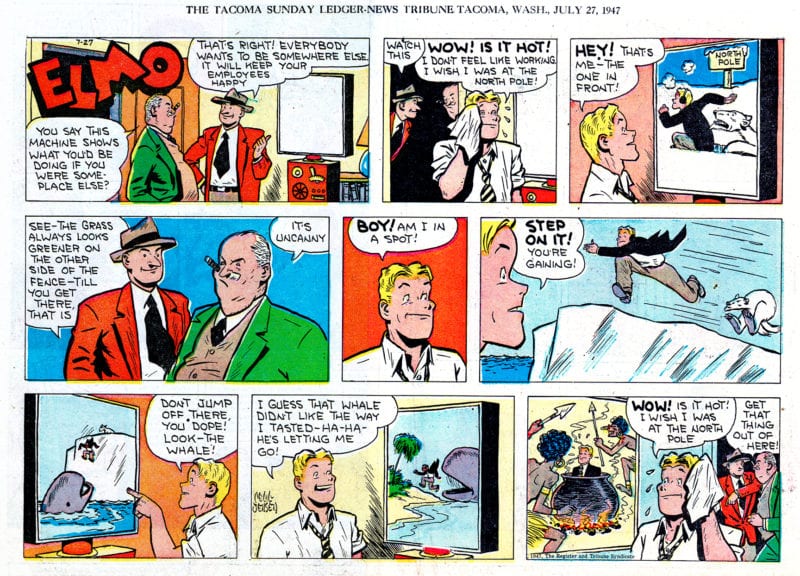

The Sunday Elmo was a stand-alone affair, sometimes vaguely in sync with the anti-adventures of the daily. Here’s a choice Sunday from 1947 that typifies Jensen’s skewed cause-and-effect comedy:

Elmo was an odd fit for the Register and Tribune Syndicate, an Iowa-based concern that trafficked in America’s dullest strips. Jane Arden, Jack Armstrong, Ned Brant, Off the Record and other R&T features were popular—Arden was in hundreds of American papers. The syndicate was commercially successful, if artistically bankrupt, before Jensen showed up.

Bubbling over with eccentric characters and dialogue, Elmo also presages the laugh-out-loud novels of Charles Portis. Jensen would’ve been the perfect artist to illustrate Portis’ low-key novels such as The Dog of the South (1979) and Masters of Atlantis (1986), had time and space permitted. Jensen and Portis heed this golden rule: the nuttier the situation, the more deadpan the delivery.

Unlike Portis or Bob & Ray, Jensen’s comedic vision is quite dark. Elmo is a strip without one heroic character. Elmo is troubling. He’s too cheerful. Perhaps all those years of washing diapers at the orphanage, where he was raised, made something snap in his head. He is civil, polite and obliging, but he doesn’t function in a reassuring way. He may occasionally frown, or display anger, but most of the world’s good and bad bounces off him. He is a challenging choice for a protagonist.

If he was inspired by Al Capp’s Li’l Abner, a strip of comparable darkness, Jensen gave Elmo a persona and presence that thwarts reader expectation, as did E. C. Segar’s Popeye in the early days of his existence. There is something of Segar's rambling ways in Jensen's narratives. Like Segar, he used a egalitarian cast of characters to achieve his quiet comedy. Elmo has one true Popeye moment in this daily strip from January 15, 1947:

His hometown girlfriend Emmaline, who soon joins him and finds work at Popnut Skrummies, is the strip’s most sympathetic character, but she is overshadowed by scoundrels out to better themselves at anyone’s expense.

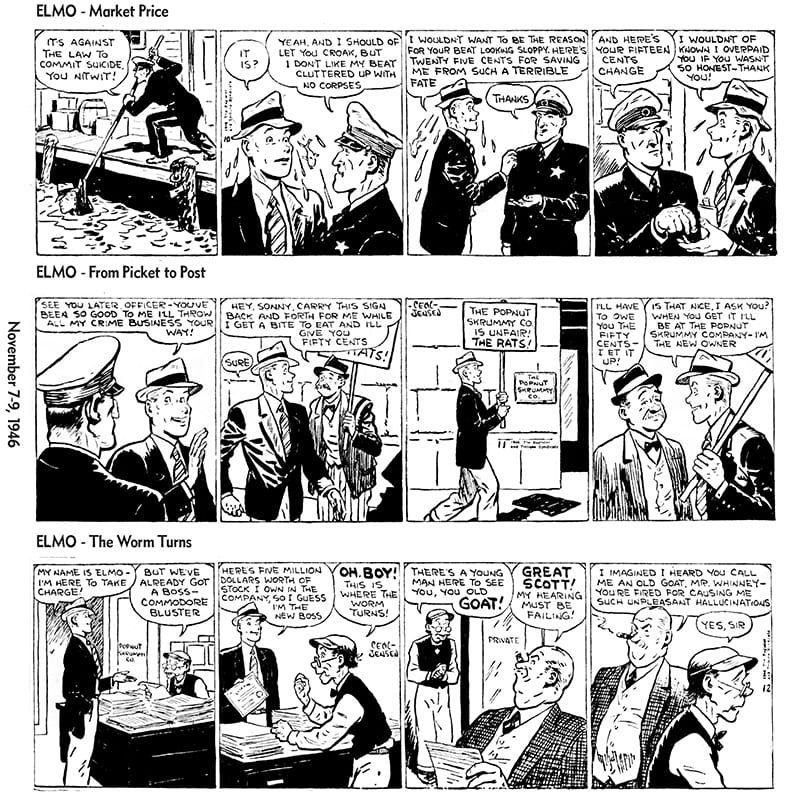

Commodore Bluster is a vile being. He is upfront about his contempt for Elmo and wishes him dead. Bluster is often seen reading a book called 1001 Ways to Get Rid of Elmo. Elmo is immune to his schemes, and never shows any emotional response to this harrumphing, homicidal plutocrat. Elmo makes one negative comment about Bluster, directed to us, the reader, in confidence. Here are some moments of malice from the early months of Elmo:

There is seldom overt violence in Elmo, but its threat looms in nearly every panel. The suggestion of hazard, followed by the realization that it’s a non-issue, is part of Jensen’s comedic sensibility. It needs to be stated that Elmo is very funny, despite the weight of its dark matter. Jensen renders these moments with real heft. A lighter, less studied cartoon style always makes violence go down smoother. Imagine Bringing Up Father or Blondie by Jensen: the brickbats might seem unbearably harsh. Though Capp’s Abner is as violent, he brought enough comic abstraction to his slapstick to tenderize it.

There is seldom overt violence in Elmo, but its threat looms in nearly every panel. The suggestion of hazard, followed by the realization that it’s a non-issue, is part of Jensen’s comedic sensibility. It needs to be stated that Elmo is very funny, despite the weight of its dark matter. Jensen renders these moments with real heft. A lighter, less studied cartoon style always makes violence go down smoother. Imagine Bringing Up Father or Blondie by Jensen: the brickbats might seem unbearably harsh. Though Capp’s Abner is as violent, he brought enough comic abstraction to his slapstick to tenderize it.

When Elmo is funny, it’s funny. Things go haywire in surprising ways. In two strips of December 1946, a tough-looking fellow named Hoodlum, a rival for the hand of Emmaline in marriage, force-feeds a score of Popnut Skrummies to the bald Elmo. (He is bald by his own choice, but that’s another story.) The cereal makes his hair grow longer than 1,000 heavy metal front-men. Hoodlum and his cohort nearly drown in hair.

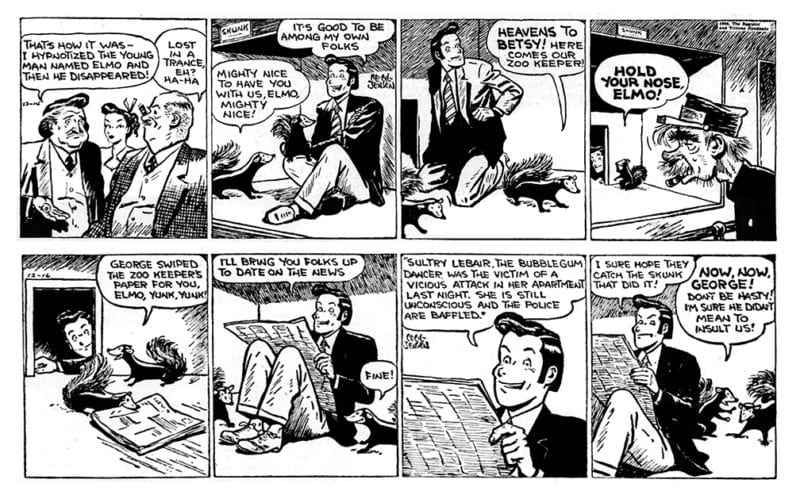

Elmo has communion with planes of existence not available to everyone. Hypnotized into believing he’s a skunk, Elmo goes to the zoo and lives among skunks.They’re able to have a dialogue and cordial companionship, though they take umbrage when Elmo refers to a criminal type as a skunk.

In an unsettling 1946 Sunday episode, Elmo feels he needs to create a father-figure to tell his troubles to. He imagines a genial ghost (portly, bearded, with spectacles and a vest) whom he talks with to get perspective on his problems. What are we to make of this? No explanation is offered (or, really, possible). It just is, and that’s all it is. We have to accept this, and other inscrutabilities, to visit Elmo’s rickety world.

Unlike Al Capp, who piled boffo plot twists like boulders in Li’l Abner, and seldom stayed the course with any of them, Cecil Jensen stuck to a narrative or comedic idea and saw it through to fulfillment. The results were amusing and maddening.

In one of the daily strip’s few “adventure” continuities, Elmo, with the help of Mr. Floote, a self-professed crazy inventor, makes a mission of mercy to deliver serum to stricken residents of Pedestriana, Jensen’s equivalent to Capp’s Lower Slobbovia. The buck-toothed Floote has developed a super-plane with one major flaw, which he chooses not to disclose ‘til the craft is in mid-air: it can’t be landed. The two, stuck in this existential flight-path, grow gaunter and hungrier, until Floote completely cracks. A sub-plot involves an elderly mother's realization that her shiftless son may have been given to her by mistake at the maternity ward. It doesn't hit comedy paydirt, but the 9/5/47 strip, with a visit to the offices of big-shot Eliot Speck, is a quintessential Jensen moment—one of many to be savored in this sequence.

Most remarkable about this storyline is how long it’s sustained. Jensen is fine with letting whiskers grow on his comedic concepts—to our benefit as readers. (It proved too much for the Cincinatti Enquirer, which dropped the daily Elmo as soon as this storyline showed the first sign of a wrap-up.)

You can download and read this sequence in PDF form, from my restorations, at this link.

This chunk of Elmo shows the strip in top form. It's hard to imagine that, one year after this sequence, Elmo would be gone from the strip. In the second part of this article, we’ll see what happened to Elmo—and how he rose from the dead when all hope was lost.

Everything happens to Elmo! The Sunday strip often makes Elmo a plaything of fate—which seldom plays fair.

Everything happens to Elmo! The Sunday strip often makes Elmo a plaything of fate—which seldom plays fair.