Introduction

Ed Piskor is one of the most fascinating young cartoonists in America. Self-taught as a child, Piskor broke into the industry when he was invited by Harvey Pekar to illustrate an American Splendor story. Impressed with the young artist’s chops on that strip, Pekar hand-picked Piskor to collaborate on several graphic novels, including Macedonia and The Beats: A Graphic History. However, although grateful for the opportunity to work with one of the most celebrated writers in comics’ history, Piskor’s fascination with ‘80s popular culture compelled him to branch out on his own and explore the fascinating world of early computer hackers. Initially self-published, Wizzywig was eventually released in 2012 by Top Shelf Comix and the fictionalized historical graphic novel earned a spot on many critics’ year end lists.

But Piskor’s dream project, which he began serializing as a web-comic on the eclectic pop culture site, boing boing, is an exhaustive history of the hip hop music scene. Partially inspired by his work with Pekar and also his own obsessive passion for the subject matter, The Hip Hop Family Tree quickly mushroomed into a monumental project, chronicling, in retro-comic vivacity, all sorts of intriguing minutiae related to the “viral propagation” of the subculture. Meticulously researched, and drawn with a keen eye toward historical accuracy, Piskor’s exploration of hip hop immediately earned him the respect of cartoonists and musicians alike, as well as a book deal with Fantagraphics (due in 2013).

Having watched Piskor develop over the years, since discovering his first self-published mini-comic, Deviant Funnies #1, all the way back in 2004, I was excited to interview him about the trajectory of his career and his plans for the future. We spoke by phone for several hours on November 29, 2012, the same night the world lost the great underground cartoonist, Spain Rodriguez.

Marc Sobel

January 21, 2013

“Drawing and Withdrawing”

MARC SOBEL: To start off, can you give me a quick background on yourself, like where you’re from, your family background and so forth?

ED PISKOR: Sure. I’m the first born of four siblings. The youngest one is eighteen years younger than me. She’s twelve now. We’re from this area of Pittsburgh called Homestead. It’s one of those areas where the only source of economic income for the town was the steel industry and that went away like two years after I was born. So we were pretty poor and there wasn’t much money to do anything but luckily pencils and paper were cheap so I was able to hang out and draw.

Also, I was one of the only white kids in my neighborhood, which was no big deal until I started getting a little bit older, like middle school age, and then it was weird. After one summer, coming back to school, suddenly race was an issue. It was confusing to me because we were all friends the previous year and then when we came back, some epic thing must have happened that I was just completely ignorant of because suddenly race was a factor. So after that I just became withdrawn and hung out by myself and drew.

I was also one of the only kids whose parents were still together, and, as weird as this sounds, that was an embarrassment to me because people would make fun of me. It’s so weird but I was really susceptible to that kind of stuff. Dudes were like ‘aw man, you live like Leave It to Beaver,’ and shit like that. Now it’s completely obvious that dudes were just jealous that I had a mom and dad who got along, but at the time I was just like, ‘oh man.’ I didn’t fantasize about them getting divorced or anything but I was like ‘why can’t I just be like everybody else?’ That sounds so pathetic, though, right?

MARC SOBEL: <laughs> No, it’s interesting.

ED PISKOR: Yeah. I guess that’s really it. Well… I could take it to a dark place. In high school, when I was 15 years old, I got really, really sick. That’s not something I like to get into but it informed where I’m moving in terms of an art career and stuff, because… I got very sick to the point where, in tenth grade I was home-schooled for the last two and a half years of high school. That provided me with copious amounts of time to hang out, draw and read comics.

The way the schooling was structured, two teachers from the school would come once a week each, after school to my house from 3:00 to 5:00pm and that’s all I had to worry about per week. So I only really had four hours of school a week.

MARC SOBEL: Wow!

ED PISKOR: The rest of the time I spent drawing. And because all my friends were in school all day, they had to go to bed early, so I started hanging out with older kids and even people in their twenties. Those guys introduced me to graffiti and things like that. I wasn’t good enough at drawing comics yet back then, but still I had this urge to put work out there and have it seen, so at that time, graffiti was my outlet to express myself publicly. Once I got better, I would stay out all night and do graffiti, then come home, crash, wake up at like 3:00pm, have my teachers come over, do that school shit, and then just do it all over again. This went on for a couple years.

MARC SOBEL: So you were sick for two years?

ED PISKOR: Yeah, but honestly, I was sick for like a year, but the recovery process took forever. What’s weird is that since getting into comics, I’ve met a bunch of guys who had that same problem. It just has to do with being so anal retentive and obsessive. It seems to be a common thing amongst a lot of creative people, which is something that the doctors told me as a kid.

MARC SOBEL: There’s definitely something about creativity and control. Comics gives you almost complete control over the world that you’re creating.

ED PISKOR: Yeah, for sure. And especially as a kid, you have zero power over anything else so you try to control that little world. Plus, you spend a lot of time in your head and it just bleeds over. But, like with everything that I do in general, during school I wanted to be the best student, but my mind isn’t a sponge for information. I know some people who learning comes easy for them, but that’s not me. I always got great grades, but I had to work my balls off for that. So that shit just caught up to me after a while. After I got sick and I was recovering, I sort of made a change, but it still creeps back now and then and when I find myself getting really obsessive, I have to take a break.

To be honest, when you first called me up, I was going through a big-time depression. It just happens every now and again because I spend so much time drawing and withdrawing. This time it was because the guys at Fantagraphics had just sent me my advance for the book and so now… I’ve never borrowed a dollar from a person in my life so now I feel like I’m in their debt, you know? I feel a big responsibility to make it as good as possible, so I just put this weird pressure on myself. I’ve always done that.

“I Can Do This Stuff…”

MARC SOBEL: Obviously, I’m guessing that you were a huge comics fan growing up?

ED PISKOR: Yeah I was. I was a huge X-Men fan as a kid, but what really opened my eyes was… One day, I think it was on the A&E television channel, that documentary from the ‘80s called Comic Book Confidential.

MARC SOBEL: Sure.

ED PISKOR: That was one of the most important things that ever happened to me, coming across that documentary when I was eight or nine years old. I remember flipping through the channels and seeing Spider-Man on the screen, so it was during the Stan Lee portion of it, and that took me aback because it was like, ‘whoa, Spider-Man’s on TV. Cool. I’m going to check this out.’ Then what follows right after the Marvel Comics stuff is the undergrounds. So they get into Crumb and Harvey Pekar and there was one scene when Crumb was talking about the transformation of Fritz the Cat and he said something like, ‘Fritz the Cat was just this character that I drew in comics as a kid,’ and they showed this image of a comic that was drawn on notebook paper. That was incredibly important to me, because, even at a very young age, I immediately made this connection, like ‘ok, I can do this stuff.’

That documentary includes all of my major influences, both at that time and forward. Everybody in that film is the jumping off point for where I would go in terms of finding other comics. Kurtzman, Eisner, Kirby, Charles Burns, Jaime Hernandez, all those dudes were super important to me.

So I watched that movie on a Friday on regular television and literally the next day I made my mom take me to the library and there was this book, it was the only book on comics in the entire library, called Comix, with an ‘x’ by Les Daniels from the ‘70s. It was great because I watched that documentary, got schooled a little bit, and then I got that book and almost everybody that was discussed in the movie is talked about in that book. Plus, there were actual, full excerpts of stories by people like Robert Crumb and – rest in peace – Spain Rodriguez.

MARC SOBEL: Yeah!

ED PISKOR: So, I feel extremely lucky because I was exposed to underground comix before I hit the double digits of age.

“We’re Gonna Be Fucking Billionaires”

MARC SOBEL: I know you went to the Kubert School for a year, but are you mostly self-taught?

ED PISKOR: Yeah.

MARC SOBEL: Talk to me about how you learned to draw. You started to touch on it when you mentioned all the free time you had, but can you give me a little more detail?

ED PISKOR: Yeah. I relate hip hop culture a lot with my learning to draw because… There’s this certain mind frame. All through school I was definitely one of the worst people at most things, but with drawing I could at least hold my own. There was no way I was going to be able to beat anybody in any kind of organized sport or anything like that but I was at least a contender in the drawing thing. And the hip hop mind frame helped because people would snap on my work. They’d say something like ‘That sucks, man. I can’t believe you drew that,’ or, ‘do you need glasses?’ Shit like that. We would just bust on each other for being able to draw. So that provided a natural incentive to do better work because I thought, ‘oh man, I have to blow these dudes’ minds next time.’ Of course that never happened. Even when I got to a point where I was reasonably sure that I was better than them, they could still cut me down, which was cool. It was character building.

MARC SOBEL: So you were putting drawings in front of all your friends on a regular basis?

ED PISKOR: Yeah, we all were. When I was in sixth grade, there was this weird period where comics were really popular with everybody. Even a lot of the jocks were into them. This was after the “Death of Superman” and the first coming of Image Comics.

Everyone was buying these things, even football players, but most people were never looking at them. A lot of dudes would have Comic Buyer’s Guides, the new ones, or their Wizard Magazines in class all the time and they would be calculating their wealth. <laughter> It was like, ‘oh man, I’m worth $15,000 this month.’ So the cool people were into this shit for a brief time and it was really a cool thing to do.

And a lot of people were drawing too. Recently I sent a bunch of my friends this clipping from an old Entertainment Weekly from around that time where, there was this guy named Chap Yaep, who drew Team Youngblood.

MARC SOBEL: I remember that guy.

ED PISKOR: Yeah. He was 19, so he was only a couple years older than us, and the article was like, ‘Cartoonist rookie stands a chance at making $250,000 this year.’ <laughter> That’s fucking crazy, man, but we were all like ‘yo, we’re gonna be fucking billionaires drawing this stuff.’ So me and all these dudes, we were submitting work to the Extreme Studios talent search to try to get an opportunity to draw Brigade comics, or Bloodstrike, or whatever.

MARC SOBEL: Wow.

ED PISKOR: It was pretty cool. So a bunch of us were always drawing and we would show each other stuff, but… We were encouraging in as much as we’d bust on each other. Like, ‘dude, you suck, man. It looks like you drew an arm where his leg’s supposed to be.’ <laughter> Then another dude would be like, ‘Ah, you’re a fucking dick,’ and then everybody’d just keep drawing. But eventually those dudes discovered chicks or something like that whereas I was just stubborn enough to keep going. I think I recognized that with each little piece I was drawing, my stuff was getting a little better. So that was incentive enough to keep going.

Another big school of cartooning for me as a kid was I would copy full comic pages off of existing books. So for a period of a few years there… and I still have some of this stuff… I was drawing whole pages from Spawn comics and Youngblood, or Rob Liefeld’s X-Force. Then my tastes gradually got more sophisticated and it got to the point where I was drawing pages from Dark Knight Returns and John Romita, Jr. Daredevil comics, and then it was EC Comics. Finally it was like, ‘ok, time to start drawing my own stuff.’

There was also an art school in town for kids. It was just one of these extracurricular things where every four quarters you could sign up to take a cartooning class. So I participated in those and I absolutely adored those classes because it was a little bit healthier of an environment in terms of learning. It wasn’t just about making fun of each other.

The best part was that eventually they put together these comic book production classes at that school. So what we would do is for eight weeks, we would work on a four or five page strip and then, at the end of the course, the teacher would go and print them up into this little anthology book. I mean, this thing was bound and saddle-stitched and it was a real comic. Everybody would get 10 copies of the book and that really started my addiction with the print medium. There were 10 or 15 people in this class so that meant there were 150 copies of my story out there. I think I did like five issues of that stuff, and it was just so great because I could pour all of my creative energy into that for those eight weeks and then I’d have a real comic book. It felt magical, like I stacked up against anybody else, even though it’s so apparent when you look through those things, that I’m literally the only person that took that stuff seriously at all. Every other kid was just there to be babysat. Like, it would give their parents three hours with the kid out of their hair. <laughter> I’m still friends with that teacher to this day and he was like, ‘dude, I always knew that you were going to end up drawing comics.’

MARC SOBEL: So was Deviant Funnies #1 your first real mini-comic?

ED PISKOR: Yeah, and the material that’s in that mini, those are the same strips I sent Harvey Pekar that put me on his radar. He gave me a call after checking out some of that stuff, although I actually hooked up with him before I printed that book up.

What I would do is draw a four or five page strip and submit that to Fantagraphics and Top Shelf with a proposal for what I would want my Eightball-analogue comic to be. My idea was to do a personal anthology, but all those stories were pretty crappy. My proposals had such naiveté attached to them, but, to an extent, I feel like that was an important component to getting published, at least for a guy like me where everything’s pretty gradual. I’m not James Stokoe, or whoever, with all this great natural ability. I have to really break my balls

So, I put myself out there and I think that was an important part of being able to get started. Nowadays, I could never see myself sending stuff to a cartoonist who I love, like ‘oh man, it would be great to work with you, Harvey Pekar.’ That’s a crazy thought to me now.

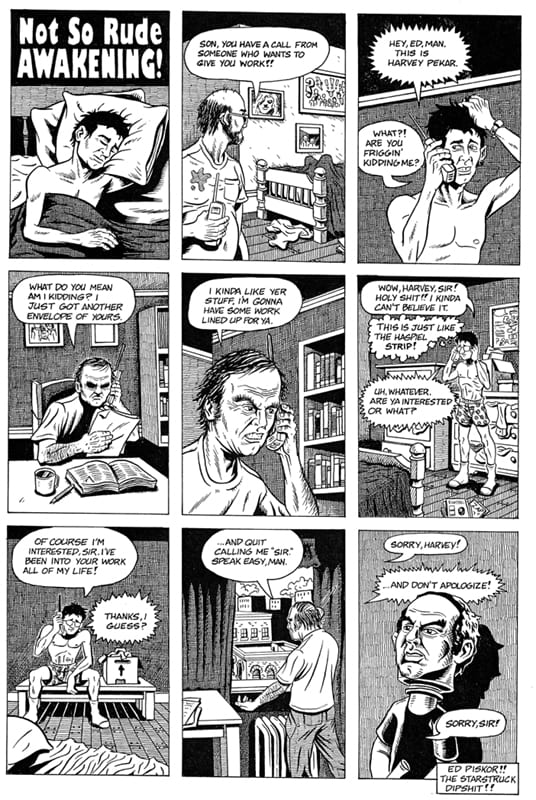

MARC SOBEL: You had that one-page strip in Deviant Funnies about Harvey calling you up, but can you elaborate about how you guys first started working together. You started out doing American Splendor strips, right?

ED PISKOR: Sure, yeah. So, like I said, I would send stuff to Fantagraphics, Top Shelf, Alternative Comics, all those places but I always would get rejected. So it was like, ‘what am I going to do? I’m just going to do these strips only to get rejected by these five people?’ That seemed kind of whack, so I started sending stuff to cartoonists that I dug. Basically I would do a strip and send it out to maybe 50 or 60 guys. So I found Harvey’s address on… I had lots of old American Splendor comics, but there was one recent one that I had and on the cover it had a photograph of his face. And it was mocked up to look like Time, or some other subscription-based magazine, where they laser print your address on the cover whenever they ship it. So it had an address and I was like ‘I’m going to send my strips to this address and just see if it gets rejected, or if it’s even a real address.’ I didn’t hear anything, but since the packages never came back, I just assumed they got to the guy.

So, the American Splendor flick comes out (in September 2003) and I dragged a bunch of friends to go check it out and just a few weeks later, Harvey Pekar calls the house. That was what that strip’s about. I just couldn’t believe it. It seemed insane. So he’s like, ‘yeah, I dig your stuff.’ Also, I think there was a part of me being from a sister city to Cleveland that was interesting to him. The fact that I was young also helped because he felt weird asking a lot of the old-timers to work for $100 per page. That’s not a lot of money.

So from when I first spoke with Harvey, it was about one year later before we actually started working together. It was this crazy waiting game. I would be in touch with him fairly regularly, maybe every couple of months or so. I would call to check in and see if it was still real. Like, ‘Hey, Harv, do you still remember me?’ He’d be like, ‘yeah, yeah, yeah, what are you talking about? Yeah, I remember you, man.’ He was like, ‘I’m still working on this thing, and as soon as it’s ready to go I’ll get these strips to you.’

So it was this long build-up and then I did a four-page strip for American Splendor: Our Movie Year. And that was it. I was like, ‘ok, well, I did that. Cool.’ And that was going to be it until the book was wrapping up. Apparently he was contractually obligated to make it a certain number of pages and they were like 25 pages shy. So, it’s like a week before my birthday and Harv calls me up and he’s like, ‘hey, do you want to do a bunch of pages in a really short amount of time?’ I’m like, ‘alright, yeah. Sure, man.’ He needed this 24 or 25 page story in like that many days, maybe even fewer, like 20 days. So I’m like, ‘OK. Cool,’ and I put my birthday on hiatus. I was just like, ‘I’ll celebrate after I’m finished with the strip.’

That turned out to be a real cartooning boot camp for me because of the tight deadline. I really didn’t want to disappoint him, so I worked my ass off to get the work done. But after some time, it became apparent that he was testing me a little bit. I mean, I’m sure we did have a tight deadline, but right after delivering, he was like, ‘Ok, man. Do you want to work on this 150 page book with me?’ Obviously I was delighted.

MARC SOBEL: This was Macedonia?

ED PISKOR: Right. And when he called it “Macedonia,” I was like, ‘this is fucking awesome. Harvey is turning a new leaf. We’re going to do a comic about Alexander of Macedon, and shit like that. We’re going to do a story about this guy taking over the world.’ I was already thinking about referencing Pythagoras and Diogenes and all these old philosophers. But then he was like ‘no man, it’s about the geopolitical de-stabilization of the Balkan region through the story of this young college girl.’ <laughter> I was just like, ‘Fuck! ...Alright I’ll do it.’ <laughter> But then I got the script and I’m like, ‘holy shit!’ He had told me that it was derivative of this girl’s thesis and I’m like, ‘yeah, it reads like a fucking thesis, man.’ <laughter>

MARC SOBEL: There’s very little visual narrative there. Was it tough to work on a story like that?

ED PISKOR: It was SO tough, and I absolutely wasn’t ready. I wasn’t good enough to translate that in any way. Also, it should have been maybe a 300 page comic, so there are pages that have maybe fifteen panels on them, and each one is just loaded down with copious amounts of dialogue. It’s like an EC Comics amount of dialogue hanging above all the characters’ heads.

That is the reason I describe Wizzywig as ‘my first book.’ All the Harvey Pekar stuff really was my version of art school. I’m embarrassed by those books because they’re some of Harvey’s last work and I didn’t show up properly. I’m not saying that I hacked that stuff out. I did my absolute best for my skill level at the time, but my skill level was just not there, you know? It just absolutely was not there and the result is that that’s some of Harvey’s last work and it’s seen through the lens of a fucking 23-year-old jerk-off.

MARC SOBEL: What would you do differently with those books if given the opportunity now?

ED PISKOR: Well, it’s been a while since I really looked at that stuff, but I would definitely try to just gussy it up with some visuals. I would try to give it room to breathe, and the overall aesthetic of the art would obviously be way better. But, to be honest, Macedonia was a hard book. I still really have never read it. I sort of read it as I went along. I read it initially in script form and was just like, ‘Fuck!’ I can’t say no, but I don’t think I’m the guy for this job.’ But I just had to do it. I wanted to draw comics so bad. I don’t know. It was so long ago. It honestly caused me a lot of pain because we don’t have Harvey around anymore and I look at some of that work I did with him as a blemish on his career. I was just so inexperienced and stupid.

MARC SOBEL: What about The Beats? How do you feel about that work? It looks to me like your art came a long way in terms of improving and tightening and developing into the style you’re working in now from where you were on Macedonia. Would you agree with that?

ED PISKOR: I would, but I still hate that artwork a lot, too. It definitely got better from Macedonia but it’s still pretty hard for me to look at. I can see all this Dan Clowes wannabe stuff, and I was using rulers on every line so it looks kind of dead or maybe constipated or something like that. That shit is tough for me to talk about. I don’t know what I was trying to do.

MARC SOBEL: Beyond just checking in periodically, did you have much of a personal relationship with Harvey? Did you guys ever meet in person or anything like that?

ED PISKOR: Yeah. In that first year waiting period, I travelled out to Cleveland and we hung out. And then he was a guest of honor at SPX one year, so we hung out there, and we gave a talk at a few colleges, too. So maybe like five times we hung out physically, but for two and a half years, I spoke to him almost every day on the phone. And that was really cool. That guy was really, really funny.

MARC SOBEL: Yeah?

ED PISKOR: Oh yeah. Every now and again, you would catch him when he was in the doldrums or whatever, but I never once got that sense of… You know how people use that word ‘curmudgeon’ whenever you bring up Harvey? I really think that’s the power of television because that’s the character he portrayed on Letterman, and therefore that’s what people remember, but he absolutely was not that guy. He was super magnanimous and cool. I never once got that ‘bah humbug’ vibe from him. If anything, there would be times when he was just kind of sad or something, but never a big grump.