This edition of GRID features ten thoughts about Daniel Clowes’s just-released graphic novel The Death-Ray, covering areas such as genre, politics, form, Freud, narration, and color. These observations are followed by three excerpts from recent interviews with the cartoonist. I encourage readers to respond to any of these comments and/or post on a topic of their choice. Perhaps we could generate something that, on the web, isn’t always too easy to get started or keep going: a sustained conversation about a comic book.

1. Grim and Gritty v. Deadpan.

Some readers have argued that The Death-Ray is the only “purely [whatever that means] revisionist superhero comic.” Other comic books may claim to fully re-imagine the superhero, but they really don’t. Like Watchmen etc. they work implicitly within, and therefore endorse, the grandiosity and power-fantasy modes of “The Superhero Story as Modern Myth.” Or they simply go “extreme” in the opposite direction, by making superheroes into super creepy villains, which isn’t really much of a revision, given that most superheroes are law-breaking, self-serving vigilanties. Clowes’s deadpan comic is perhaps the lone “realistic” [whatever that means] superhero comic.

2. What The Death-Ray Is Not About.

The Death-Ray really has nothing to do with superhero comics—it’s a character study disguised as a superhero story:

It's really the story of two boys and their complex friendship, which slowy turns into a deadly rivalry. Like Clowes's Wilson, it's about the need for companionship.

To focus on genre is to miss the point. An interviewer once asked Clowes the following:

Q: Did you think of The Death-Ray as a kind of critique, in this case of problems you saw with superhero comics or their readers, who might respond to these stories primarily as violent revenge fantasies and not as ennobling tales of justice? Like Andy, the average teenager who gets a superpower would go around killing people who were mean to them or their friends or who spit on pigeons.

A:[Laughs.] I didn’t do it to make anyone feel bad for reading superhero comics or to make them reexamine their choices if that’s what they like to do. It wasn’tabout that, necessarily. . . . You know, it’s not about anything; it’s just about this particular character having super powers, a guy I understand completely inside and out, and about what that would mean, and really following that up and not thinking at all about other superhero comics as I did it. [source]

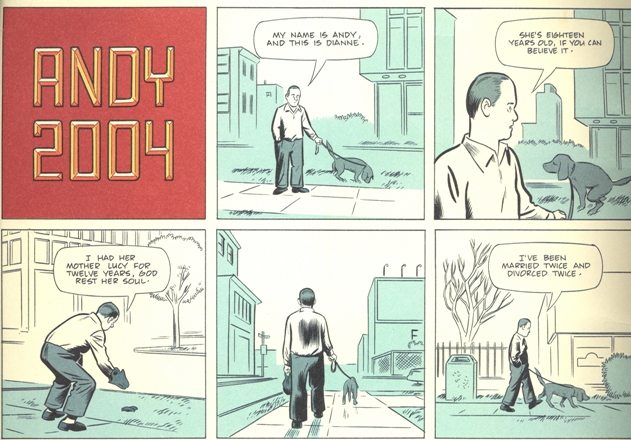

Note the reference to Livermore, Ca. Andy's father was a scientist, and gave his son superpowers via an injection of a special hormone. Perhaps when in Livermore, he worked at The Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, which played a key role in WW II and post-war US military weapons development. Maybe Andy's origin is tied to this place and US government experiments . . . They also lived in Tennessee, where Andy's father "worked at a lab": an important atomic research facility for The Manhattan Project was located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Andy's deep origin seems to be connected to origins of many '60s superheroes, whose stories involve atomic power and experiments.

3. Occupy Comics.

Has Clowes finally gone all political on us? Forget Frank Miller’s crazed anti-Islam comic Holy Terror, The Death-Ray takes on the unholy War on Terror and an American Mind that's in thrall to a foreign policy based on aggro forms of acting-out against flamboyant international super villains/dictators: The US government as global mass-murder who justifies its crime with the rhetoric of 'god-sanctioned American exceptionalism.' By the comic’s end, has Andy has morphed into a pudgy Rush Limbaugh-esque commentator on American values, a man who who wishes he could project his personal death-wish on the world?

Can we take this socially-invested comic as an invitation to reread Clowes’s earlier stories in political terms? Is Wilson, for example, an exploration of the plight of a marginalized 99%-er? Is his lack of ambition and complete rejection of conventional modes of success (i.e., $$$) an explicit indictment of cherished Tea Party principles as promulgated by Fox News? (hmm; perhaps that analysis goes too far).

4. Ditko in The Death-Ray.

This comic displays Steve Ditko’s crucial influence on the young Clowes, who was fascinated by Ditko-drawn and plotted Spider-Man issues. This influence has been at work throughout Clowes’s career, though often buried in his current ‘aesthetic unconscious’ in ways not always instantly recognizable. Both artists share an obsession with heroic and un-heroic action, frailty and ugliness, revenge and violence. According to Clowes, he has even turned into a Ditko character!: “Now I resemble The Vulture from the early Steve Ditko Spider-Man comics” (source: Ghost World: Special Edition).

Every time Clowes draws a water tower,

In recent interviews and features, Clowes talks about the seminal cartoonist:

a. When I was about Andy’s age, about 16 years old, I was obsessed with the Steve Ditko Spider-Man comics, and I was so moved by them that I tried to create… Well, I didn’t think of it at the time as my own version of that, I thought of it as something totally unique, but it really involved the same emotions. It was about a kid who lived with his grandfather, and his grandfather was killed, and the kid was bent on vengeance. The kid had these superpowers, and I didn’t bother to figure out how he got them, but he also had this ray-gun. I think I’ve had the fantasy of a ray-gun that could erase the world from the time I was a very little kid. [source]

b. When [Clowes] was 18 years old . . . he tracked down the reclusive cartoonist Steve Ditko, co-creator of Spider-Man, who happened to be living above a hardcore pornography theatre in New York. “This was before 42nd Street was like a Disney store,” said Clowes. “This was a really sleazy area; it was right out of Taxi Driver.” When he finally made it up to Ditko’s front door, though, all he got was a fleeting glimpse of the apartment and a door slammed in his face. “That was probably the greatest moment of my life.” [source]

5. Freud and Feces.

The Death-Ray takes up where the short story “Black Nylon” (1997) and graphic novel David Boring (2000) left off, furthering Clowes’s exploration of (parody of?) Freudian ideas within an action/adventure context.

The Death-Ray opens with a covert allusion to Freud’s concept of the “anal stage.”

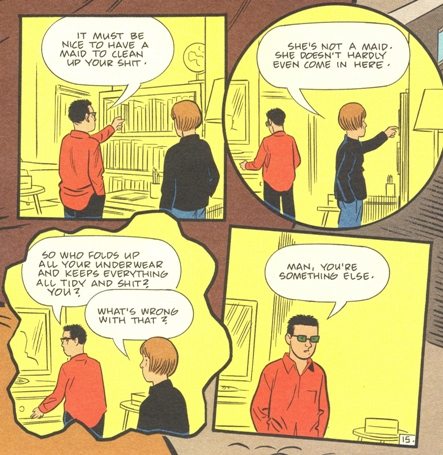

During this stage of development, children are invested in controlling the release of their urine and fecal matter. If parents practice improper toilet training (punishing rather than praising or being overly strict), children develop an anal retentive personality, becoming inflexible and obsessed with order and cleanliness, just as our hero is:

The incident that bookends the narrative is a scene in which Andy gets very angry because he sees someone littering . . .

Is Clowes saying that the superhero’s origin story is traceable back to his toilet training!? Ha! Is the superhero sometimes/always a “case study” in stunted psycho-sexual development?

6. Colors: The Pink Spine and The Yellow Streak.

In Clowes’s David Boring, the title character’s father created a superhero named The Yellow Streak, an name synonymous with cowardice. Clowes once said all “superhero comics are, on some level, autobiographical”— by choosing this name, is David’s father unintentionally revealing something about himself? (after all, he later abandoned his family, surely a coward’s move).

How are we to interpret the pink spine of The Death-Ray. To what aspect of the superhero story does it refer? Why such a prominent place on both spine and front cover? Color has narrative, symbolic, and emotional meanings in the comic, so why not here?

7. The Great Easily-Overlooked Moment.

The story is full of them. One of my favorites is Clowes’s use of the “non-character reaction shot.” After Andy reveals his tragic family history, Louie has no response, failing to sympathize with Andy’s plight. (This failure condemns Louie, the story’s true villain—a sidekick motivated by jealousy of the hero’s power.) The media image—George Jetson’s pained face on the TV—provides the appropriate “reaction shot” to Andy’s revelation. Why is it that we let the media and cartoons do our feeling for us?

8. Color, Lines, and Visual Narrative Unreliability.

The muted color scheme (even Andy’s words are “colored”) may suggest that the story’s visual narrative (which is often distinct from Andy’s narration) is unreliable.

When we begin reading, we leave the full color of our reality and enter “Andy’s World” (a chapter title). Clowes’s muted visual choices here become narrative choices; they signal that something’s not right with our narrator—things are missing, lines don’t come together. What at first looks like objective third-person visual narration is in fact subjective. Similarly, in the next chapter Clowes doesn’t complete the living room blinds next to Andy: they just stop. The visual POV here is also third-person, but its objectivity, too, is compromised. Maybe Andy’s unreliability has infected the visual narration.

9. New Graphic Forms of Narration.

The slightly pointed corners of the first two balloons indicate its unusual function, so calling them a “word balloon” doesn’t seem right. Let’s call these a “past-tense narration balloon” (many of Clowes’s narration balloons are present-tense). This sequence and those that follow feature a narration balloon fully situated in two panels: the first has no border (signaling its connection to Andy’s interiority) andthe second does (signaling its connection to exteriority). The white gutter between panels typically represents un-narrated time. But here this function is erased—the voice-over narration binds both panels into a single unit of “trans-chronological narration,” another Clowes innovation. Andy 2004 speaks from the future through Andy 1978 as he lights up for a fight. This cross-temporal split occurs at a psychologically and physically traumatic moment: Andy soon goes ballistic on the school’s macho jerk Stoob, who’s pummeling Andy’s friend Louie. Though it’s an odd and unwieldy name, I might call this mode something like first-person past-tense textual narration (delivered from the future) with third-person past-tense visual narration. Regardless of the term we use, Clowes’s narrative approach makes for a compelling and haunting scene. (Look at the strange intensity in Andy’s eyes.)

10. Fantasy and Form.

The Death-Rayis a fantasy in the sci-fi, superhero sense: impossible things happen. As the above scenes show, it’s also a fantasy in its approach to form, mixing realistic and artificial narrative elements—the possible and impossible—throughout the story, and even in the same panel. Who is the visual narrator in scenes where the teenagers’ dialogue is superimposed on superhero imagery?

If the entire comic portrays Andy’s memories, as many readers (wrongly, I think) claim, then the answer’s clear. But perhaps Louie makes occasional cameos as visual narrator. More so than Andy, he’s obsessed with superheroics. It infects his thinking; he talks about the Hulk and yells catchphrase-worthy dialogue like “It’s Justice” as they beat someone up (perhaps unjustly). Or is the visual narrator (a disembodied ‘character’) mocking both characters’ power fantasies, showing how silly they look when visualized: two scrawny boys in long underwear playing Spiderman and Batman?

Clowes Interview Excerpts.

An Artistic Creation/Destruction Allegory:

A: I'd say that someone who draws comics for a living is very likely a guy or gal who's in search of some form of control over something. I draw comics, it often seems, to relieve my anxiety over living in a world that seems dangerously chaotic and random, so it would only make sense that the characters that seem the most interesting to me are those with the same sort of issues. Having the power to erase human beings from your comics (or perhaps to cover them with Wite-Out) is not so dissimilar to wiping them out with a ray gun. [source]

Cutting Off Dialogue in Comics and Film:

Q: . . . many word balloons and narration boxes overlap each other in varying ways. Is coming up with a new approach like that a challenge you set for yourself, or did it grow out of the story?

A: Yeah, it just grew out of necessity. I think I began doing that in The Death-Ray, and I think I learned it a little bit from writing screenplays. I’veoften found that dialogue works much better if you cut off a line before it’s finished: a guy starts to say something andanothercharacter cuts him off, so you don’t really get the whole picture of what he’s going to say. Sometimes it’s much more powerful that way, so I was trying to figure out a way to make that work, trying to capture that sensation of not quite being able to make out what people are saying beyond a few little snippets.

On Frank Miller and The Motivations Behind Criticism:

A: I said something mean about that guy Frank Miller one time because I don’t like his comics. I was just goofing around. But then of course I met him and he was like, “I love your comics,” and oh God, I felt like such an asshole. [laughs] It’s usually all just based on jealousy or some misconception about what they’re doing or something. It’s rarely that you really think their work is destructive. Though in Frank Miller’s case I would say that’s possibly true. [source]