If I was able to keep up a pretense for a moment, I would pretend this is not a confession at all, but is instead expert coverage of the 29th Salón Internacional del Cómic de Barcelona, which I attended, full of tapas and Voll-Damm, over four days in mid-April at the base of Montjuïc. But I’ve never won a game of poker in my life. This is a guilty admission with some stuff about a comic convention gracelessly wedged in the gappy bits. It is a coat hanger over which I will drape a heartfelt apology to Mr Busiek’s wife.

And so:

I’ve been to comic events all over the world. In fact, there was a time in my life when I thought the whole world was just a backdrop for comic conventions. The idea of attending one no longer fills me with joy, but instead stomach-churning memories of previous shows that smelled of unwashed dudes and Mylar bags, where tiny blue squares obscure cartoon nipples, and down the endless aisles of sci-fi merchandise waddles the requisite obese Slave Leia. Conventions in America, New Zealand, Australia and Britain tend to confirm what I already know, but it turns out European festivals show me everything I’m missing.

It started regularly enough, with a line of the undead circling the block, adjusting their dangling eyeballs. By entering the building through Press Room catflap on the side, the first floor you have to traverse is that of the Zombie Room, where a bloodied, torn version of the convention’s own logo hangs in tatters from the ceiling. Arriving this way “is definitely a metaphor – I don’t know for what, but it is,” said the as-yet-unharmed Kurt Busiek, as we sidled past the gaping wound on the cheek of the zombie security guard. Val Lewton films played on a constant loop, the mere flash of I Walked With A Zombie bringing back the guilt of summer afternoons wasted on my own horrific obsessions. Zombie bands yowled psychobilly songs into gore-spattered microphones, and a zombie stand-up got a standing ovation. The chained undead leapt at frightened children, squirting blood from a breastpocket flower, while beside them cosplay girls stitched bloodied rags onto their skintight costumes.

Miles of original zombie art made this the biggest exhibition in the convention’s 29-year history: There was Dylan Dog, Toe Tags by Romero and Tommy Castillo, a tie-in poster for Romero’s Diary of the Dead by Charlie Adlard (who won the Best Foreign Publication award for his work on Walking Dead, of which there were also several pages on show), Martin Mystere by Giancarlo Alessandrini, various pages of manga by Hidishi Hino, Marvel Zombies by Fernando Blanco, Victorian Undead by Ian Edginton and Davide Fabbri and countless other bits and pieces by the likes of Jordi Bernet – a hoard of the undead closing on Clara as she turns her pout and pert bottom to the camera. Qué asco!

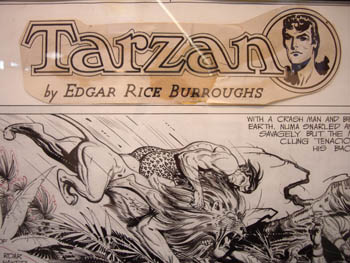

I became so used to zombies in everything that by the time I got round to the regular art galleries, I’d finish looking at a page and wonder what happened to the bit with the dead people. This was true of an exhibition of magazine covers and whatnot relating to 23-F, a failed Spanish military coup in February 1981, as well as the astounding collection of original Tarzan art by Hogarth, complete with yellow glue stains on the logo and the occasional red ink that Alex Toth was a fan of, too. For me the best part about seeing original art is the recognition that no one is actually as perfect as you think they are, and that perhaps by extension you’re not as hopeless as you believe yourself to be. I remember seeing a London exhibition by the great Quentin Blake -- a complete collection of his illustrations for Roald Dahl books. It was a rare face he got right on the first go, and he’d cultivated such a jagged mountain range of wite-out that some of the images only made sense front-on. But having now squinted furiously at the exquisitely, heartbreakingly, smooth lines of Burne Hogarth in person, I can tell you that if I had any dreams of being an artist that day I would have snapped all my pens and gone home.

By this point I had entirely forgotten about the zombies, except for when I had to wait for one to shuffle off so I could get a better look at whatever he’d just posed next to, which in this case was Krazy Kat originals. Fucking Krazy Kat originals! I couldn’t believe it. I’ve loved Krazy Kat forever (thank you, Bill Blackbeard) and to see them in person, on a wall surrounded by oblivious kids in cosplay, was an unexpected and savoured treat. There were two pages in a gallery of cat-themed art, alongside Bud Fisher’s Cicero’s Cat (1947); a Felix from 1915 and another from ’29; a rainbow feline by Moebius; Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts; Blacksad; aren’t-cats-cute stuff by Jeffrey Brown; and countless more. I was asked to pose next to a display of covers from Pumby – a 1950s Spanish strip with a design not dissimilar to early Mickey Mouse – for a newspaper photographer, so if any Spanish readers were greeted by my big white face staring at them over their morning cereal, I am sorry.

One Herriman page was an early black and white one from August 1914 in which Krazy is showing Ignatz how to use an “ole grikk yimilmint of war, dollin” called a “ketta pulp” (I met the poor guy whose current job is to translate Krazy Kat for Spanish editions. I wished him all the luck in the universe). The other was a full-color page I’d never seen before in which Krazy decides he must make use of the advantage “kats” have of looking at kings, and bounders off to look at one before they’re all assassinated, fired or decide to abdicate. It’s dedicated to Tom MacNamara “in whose prolific noodil this idea was conceived – and to whom I humbly apologize for having so miserably misinterpreted it”.

The sheer abundance of genius on the walls made it all too easy to overlook the fact that two actual living comic book geniuses were on the premises, namely Edmond Baudoin and Mariscal. I did miss the panel by Mariscal, a legendary Spanish cartoonist who appeared in Raw back in 1980, has done some cracking New Yorker covers and designs furniture, interiors and posters. He also designed the excellent bag you would get as a free bonus gift if you bought a certain amount of stuff at the FNAC bookshop in Barcelona’s ex-bullfighting ring, a bag you apparently could not buy on its own but they let me do it anyway after much miming and failure to communicate, during which I was heard to say, “BUT I CAN’T READ A SINGLE BOOK IN THIS WHOLE JOINT” because it was, in fairness, totally true and I can’t. Good bag, though. Mariscal is someone who goes beyond the field of comics, leaping over the fence to become the cartoon Picasso responsible for the enormous smiley-faced lobster atop a Barcelona restaurant that my cab sped past in the wee hours. But I heard it was excellent, the panel, and while I’m kicking myself for missing it I wouldn’t have understood a word of it anyway.

I was, however, lucky enough to be present for Baudoin’s publisher’s party, which – unlike the comparably stiff, hard-nosed English ones I know so well – was a totally lovable event, one of those magically perfect things I’ll remember forever. It was just nice, no pretention, totally joyous: a Labrador dog sat sleepily in the corner, there was a sense of something happening (and not just the Barcelona Vs. Madrid game), people were merrily drunk and kissing each others’ bald heads.

I had spent the day sitting in the Astiberri booth as my jet-lagged savaged Dad, Eddie Campbell, signed and sketched his way through the afternoon, occasionally turning to say things like, “Argh, my mind’s wandering – I accidentally gave Gull glasses,” or, later: “I’ve just done the worst drawing of my life in some guy’s From Hell. I feel awful,” to which I replied, “Well, look on the bright side. At least you’re not him.” I had ample time to flick through Astiberri’s collection – a small publisher who has somehow managed to bag a phenomenal number of top-notch creators for Spanish translation. Their booth was all the colours of a space-age candystore, featuring the likes of Jeff Smith, Jason, Jeff Lemire, Paul Hornschemeier, Raymond Briggs, Dylan Horrocks, Guy Delisle, Jessica Abel, Lewis Trondheim, Andi Watson, Chester Brown, Jason Lutes, Nick Bertozzi, Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Scott McCloud, Craig Thompson, Jason, Matt Groening, Scott Morse, Ben Katchor, Johnny Hart, Joann Sfar, and Jules Feiffer. Even Andy Riley’s suicidal bunnies put in an appearance. Those are just the names I recognized. Each book was a more handsome version than its UK or US edition, on paper of such creamy quality it doubled the thickness of the spine. It’s as if they were designed with no thought as to the cost of freightage, and probably they weren’t. Laureano, the enthusiastic mastermind behind the whole arrangement, doesn’t even mind if they fail to make a profit: “We do books that we love,” he said. “Sometimes they don’t sell,” he shrugged.

The most beautiful books on the table were by an artist I’d never heard of before because none of his stuff has ever been translated into English, a wrong I selfishly hope will soon be made right so I can read the damn things – Edmond Baudoin, a 69-year-old French artist who draws women in all their realistic sexiness, and whose party trick is to paint live, illustrating the mood of other performers. At a convention ten years ago he painted the abstract movements of a live dancer – at this, Astiberri’s 10th Anniversary party, he painted the music of a jazz band.

When the band put down their instruments and picked up booze instead, Baudoin (who speaks no English) motioned to Campbell (who speaks no French) that one of the six black inky paintings was for him. In his joyous haste to help Baudoin remove it from the easel a substantial chunk corner was left behind. Campbell held the painting aloft and shouted, “Magnifique!” while Baudoin grinned, all teeth and loveliness, and bowed humbly in lieu of English.

Campbell’s attempt to preserve the artwork by rolling it incrementally worsened the tear, until he was saved from inconsolable heartbreak: a nameless girl helped him, offered the elastic from her hair. After, at the hotel, ragged translators slumped like rumpled coats in the hotel bar, while Glenn Fabry – the ghost of the Plaza Espanya – drunkenly wandered the hallways at night trying to show someone his new book.

I caught one panel by virtue of following the elder Campbell around in case dinners happened. It was on graphic novels, biography and autobiography with Reinhard Kleist, Camille Jourdy, and the provider of dinners himself. Given that no panel members hailed from the same anthill – Germany, France, and Scotland, respectively – each sentence had to be translated for the benefit of somebody, be it audience members or other panelists. Some parts went through the human babelfish so many times I wondered how much of what I understood was actually what was said in the first place. It was a good panel though, and from the two-thirds I got it was agreed that fiction causes a disconnect: it puts an object between the author and the story they are trying to tell, while autobiography talks directly – it’s an intimate exchange between author and reader. “Writing about the life around you makes you more interested in it. You’re seeking out details instead of wandering around in a sleep,” said Campbell. “We live in a world where we’re interested in the minute details. Reality TV, Paris Hilton, etc. The whole world’s going that way. I think there’s still room to make art out of it instead of parading our banality for all to see.”

When asked about the differences between creating a full-length graphic novel versus a two-page story, Campbell said you have to think up tactics for holding the imagination. “It’s like writing a symphony when previously you’d only written a song.” Laureano of Astiberri later told me that in Spain the scene is such that even very young creators have to deliver a full graphic novel straight off. There are no magazines where works can appear in parts to be collected later. The market has changed completely. It’s harder, and there is no natural progression from novice to pro.

Reinhard Kleist talked about the huge autobiographical scene in Germany, almost none of which has been translated thus far. He himself has worked for the most part on biographies – winning several awards for his Johnny Cash book I See a Darkness. “I want the reader in the book, in the story, I want him to forget he’s in a chair, in his room, reading a book. I want to take him to a Johnny Cash concert. That’s what comics can do.” His new book Castro grew from a trip to Cuba he made in 2008 to make a travel book, after the success of stuff like Craig Thompson’s Carnet de Voyage. “The readers want to see the world through the eyes of an artist. Something personal they can connect with instead of cold hard facts.” In every book, he tries to impart a message: in I See A Darkness he was commenting on freedom and jail, and the bars we build around ourselves. In Castro it’s about ideals – how to fulfill them, and how to deal with it when it all goes tits up.

This idea of what a book is “about” rather than its actual plot was a recurring discussion ‘round the breakfast table, when everyone wasn’t on about Adobe Photoshop versus Corel Paint versus Google SketchUp (didn’t you guys used to talk about brushes?). Variations on the How Did I Get Here conversational tangent also filled the air above our chorizo and chocolate cake buffet: Busiek on Page One of how he got into comics, and the more immediate Dave Johnson by luck of Eduardo Risso’s expired passport. Busiek relayed some wisdom from Devin Grayson about breaking into the business. “Find a way in that doesn’t have any rules against it because as soon as you’re in they’ll make rules against it,” he said. “It’s like a top secret compound – the minute someone finds a hole in the fence they patch it up.” He began by writing back-ups and fillers, but “Knowing what I know now, I never would have tried it because I know it doesn’t work. Knowing what I know now, I’m stupider than I was then.”

They could have been his last words if it had all gone horribly wrong up that mountain. With a great big block of FREE TIME marked on all of our timetables, the elder Campbell and I decided to go and be tourists. It just so happened that Busiek wanted to be a tourist, too. Park Güell, a mountain covered by a massive Gaudi-designed garden complex full of gingerbread houses, mosaic dragons and thousands of children on school trips was to be our terrible choice of destination. Halfway up that rocky peak Kurt wheezed “If I kept up this level of exercise every day, in a year’s time I will have been dead for eleven months.” Had we spent another ten minutes walking directly vertical our unfit selves would have to have been helicoptered out and our mums phoned immediately. When I told David Macho what we’d done with one of his prized guests that afternoon he nearly finished the job the mountain started on me. “It’s fine!” I swore, mid-strangle, “And if it’s not then you can push Kurt around in a Hannibal Lecter trolley. At the very least it’ll give me something to write about for The Comics Journal.”