At a gallery opening a few years back, I ran into Ben Katchor and asked him what he was working on. “A history of eating out” he responded. I didn’t take that claim completely literally, but it has indeed proven to be the case. The Dairy Restaurant is nothing less.

At a gallery opening a few years back, I ran into Ben Katchor and asked him what he was working on. “A history of eating out” he responded. I didn’t take that claim completely literally, but it has indeed proven to be the case. The Dairy Restaurant is nothing less.

I’ve known Ben since 1980, when as contributors to the first issue of Rawwe met on opposite sides of a long folding-table assembly line at the Collective for Living Cinema on White street in Soho, dutifully affixing colorful tip-ons to the magazine’s black and white cover with library paste. A decade later we both found ourselves supplying weekly comic strips to The New York Press, and more recently, teaching at the Parsons School of Design. You may know Ben Katchor as the McArthur Foundation “genius award” winning cartoonist, or as the opera librettist and production designer extraordinaire or as the creator of numerous books of comics and graphic novels, including Hand Drying In America, The Cardboard Valise and The Jew of New York.

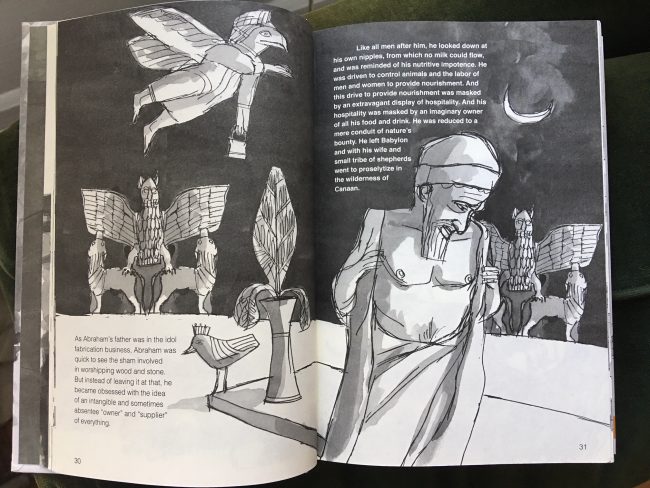

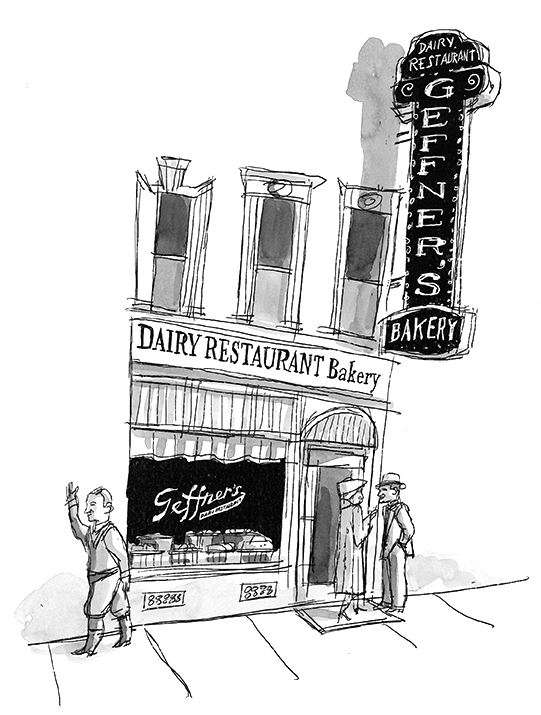

The Dairy Restaurant however is not another book of Ben Katchor’s comics. In fact I have never encountered another book quite like it. It starts off in Eden, with the fall of man and almost 500 pages later, seemingly by the process of elimination, arrives at some of the author’s mealtime experiences in a straggling handful of New York City dairy restaurants. It has the heft and flavor of a comprehensive grade school history textbook; however it is not didactic, often playful and at times laugh out loud funny. It is densely flavored with the author’s savory drawings (at least one per spread, often several) yet I would be hard-pressed to describe it as an “art book” either. In the end it remains something unique and elusive: a bountiful steam-table of history, myth, religion, biography, sociology, linguistics, hard data, speculation, obsession, digression, confession, eyewitness recollection and imagination.

Mark Newgarden: Let’s begin at the beginning. Can you briefly explain to a younger-than-us 21st century internet reader exactly what a “dairy restaurant” is (or was)?

Ben Katchor: Eating places catering to the pastoral impulse were a worldwide phenomenon. The German milchhalle and meierei, the pudding shops of Istanbul, the latteria of Italy, the French cremerie, etc. — these can all be seen as varieties of the dairy restaurant. They featured supposedly farm-fresh milk and milk products and a menu built around the rustic national cuisines of their country. Among the Jews of Eastern Europe, a certain kind of dairy restaurant developed that was based upon the observance of Jewish dietary laws that forbid the mixing of milk and meat. The Jewish dairy restaurants that I knew flourished in New York City through the 20th century. They featured a menu built solely around dairy products (cheese, sour cream, etc.), vegetables, fruits, grains and fish. Popular dishes were blintzes, vegetarian beet borscht with sour cream and a boiled potato, gefilte fish and smoked and cured fish of all kinds. This menu of Eastern European dishes was augmented with standard American luncheonette fare — sandwiches, salads, soups — but all made in accordance with Jewish dietary law, so no meat ingredients were used. They were far fewer dairy restaurants than meat restaurants or delicatessens.

This book has an astonishingly broad scope, although you acknowledge at the end that you may have only scratched at the surface of a complete dairy restaurant history. What was the impetus for a project of this scale and how long did it take to realize?

I was always interested in the remnants of working-class Eastern European Jewish culture as they existed in New York City. I began talking to people involved in the Jewish restaurant business back in the 1980s. As I recall, the The Dairy Restaurant was commissioned when Nextbook was formed in the early 2000s. They started a series called Jewish Encounters, long essay-length books about various aspects of Jewish history and culture. The editor, Jonathan Rosen, asked me if I wanted to write one and I suggested the subject of the dairy restaurant. Most of these books offered an author’s new view on a well documented topic: Rashi, Benjamin Disraeli, The Life of David, etc. — in the case of the dairy restaurant there was no established history to look at, and so it became a long term research project of compiling that history. I went through a few very patient editors.

What were some of the factors leading to the proliferation of these dairy restaurants?

What were some of the factors leading to the proliferation of these dairy restaurants?

If we’re talking about the Jewish dairy restaurant, there was a proliferation of dairy restaurants in the cities of Eastern Europe with large Jewish populations in the 19th century and that had to do with the rise a middle-class that ate out, vegetarianism and Jewish dietary law. The same factors, on a larger scale, came into play in 20th century New York with the addition of popular disgust and distrust of the meat industry.

This is as much a book about dairy restaurants as it is about the people that owned, operated and frequented dairy restaurants. In the book you actually differentiate between milkhik and fleyshik personalities. Can you outline these categories of humanity? (And is there a pareve personality?)

The milekhdiker personality was someone who chose not to fully participate in the world of action, a daydreamer, an obsessive ruminator, an intellectual paralyzed by thought. The fleyshik (or meat eater) was the opposite: an appetitive, rapacious individual pushing themselves through lives driven by appetites and unconcerned with the effects of their actions— basically, those who mindlessly go along with the profit-driven market economy. Maybe most of us are pareve personalities torn between those two extremes.

In The Dairy Restaurant many direct parallels between these kind of establishments and various brands of utopian thought are drawn. Can you share some of those connections — and can similar parallels be drawn between other political philosophies and any corridor of the food service industry?

In the early 20th century eating out was a political act. You’d choose to patronize the cafe or restaurant whose owner and clientele were in tune with your political beliefs: socialism, anarchism, vegetarianism, etc. The hearts of the owners of these ideologically driven places were not on business, many were small, marginal operations that didn’t last long. Even Communist party’s cooperative cafeteria on Union Square didn’t last long. Today, someone who thinks about the politics of where they choose to eat out will probably starve.

What were some of the factors leading to the (near) extinction of these kind of places? Why are they so hard to come by today?

A large portion of the potential clientele for Eastern European dairy dishes were murdered during the Second World War. Jews in American discovered world cuisine and many gave up on dietary observance, so they could have a blintz at a Polish restaurant that also served meat. In every Orthodox or Hasidic neighborhood there still are “kosher” pizzerias serving Italian and Middle-Eastern cuisine. These are technically dairy restaurants. It’s the dairy restaurant serving a full range of Eastern European dairy dishes that’s disappeared.

Tell us a little bit about your research methods and how they impacted the shape of the outcome.

I followed a milekhdike or aimlessly ruminative approach to my research. I would stumble upon information by chance, be introduced to people involved in the restaurant business and read widely on subjects obliquely connected to the subject.

What were some of the surprises or revelations you experienced in researching this project?

What were some of the surprises or revelations you experienced in researching this project?

I was surprised to discover the history of Jewish dairy and vegetarian restaurants in Europe. I discovered a dairy character in the works of Sholem Aleichem who is far less well known than Tevye the Milky One.

Milk toast? Mamaliga? Protose and Nuttose? Were you able to sample any of the more obscure dairy dishes cited here in oral histories and period menus?

Milk toast vanished from menus in my lifetime so I never sampled it. I thought a lot about it and realize that its preparation would depend on the type of bread used for the toast, whether the milk was hot, cold or tepid, etc. It falls into the category of invalid dishes such as sago pudding, soft-boiled eggs with bits of toast, etc. I’ve had various kinds of corn meal polentas and puddings but never in the baked form of Mamaliga with Kashkaval cheese. That dish also vanished from most dairy restaurant menus in my lifetime. It’s still being eaten by many Romanians, so it’s not hard to get. Protose and Nuttose (canned vegetable meats substitutes) were still being used as an ingredient in vegetarian chopped liver in the 1980s, so I must have eaten them without knowing — but never straight as a Protose steak or cutlet.

The drawings in The Dairy Restaurant are, to my eyes, among your finest. Each feels like a spontaneous glimpse into a scrupulously observed past, though I imagine many were necessarily channeled without direct reference. Can you tell us a little bit about your process for illustrating (and laying out) this book?

There wasn’t a lot of reference material as most of these restaurants fell below the notice of documentarians and newspapers, so I resorted to reconstructions based upon the little evidence I could find — in some cases just verbal descriptions. Only in the mythological sections and first hand memories did I use the invented spatial description of a comic-strip. If I approached the whole thing as a comic-strip it would have entailed lots of invention and then it would have read as historical fiction — something I wanted to avoid. I designed the book myself. My models were the illustrated Yellow Pages of the 1950s, tabloid newspapers and those complex pages of the Talmud with commentaries. Its the aesthetic of working-class printers that I like.

You wanted to avoid the book reading like historical fiction - and it does, however there is clearly a certain amount of creativity and invention co-existing along side some very hard data. Did you start with a plan on how you wanted it to read - or did the form develop in the process? I can’t recall another book that mingles so many approaches.

Some people see all historical writing as fictional recreation. For me the line is drawn when the author goes beyond the announced recreation of objects in space to clarify some historical fact — such as the informed reconstructions of an archeologist — and starts to play out an imagined drama in time and invent personalities that respond to those dramatic situations. The Jew of New York was complete historical fiction in comic-strip form. In putting together The Dairy Restaurant I was conscious of not crossing that line. The drawings are physical demonstrations of ideas raised in the text, but stop there. I also wanted to make a book that used many forms of text-image writing: comic-strip, illustrated text, annotated drawing, schematic drawing, etc. Also, I limited the reproduction of artifacts to typographic objects (matchbooks, menu, etc.) as opposed to photographs of places or people.

This is a tangent question but for me one of the funniest moments in the book was an extract from a 1902 New York Times rant about the unsavory sort of people who consume pie: “…The effects of pie are, like those of other injurious food, insidious. The hardened pie eater becomes art blind. Nothing makes him glow or warms him to any enthusiasms but his chosen food. No great man was ever fond of pie. No important work was ever consummated on a pie diet...” Did you follow this trail? Was it a commonly held view at the time?

That article was offering a humorous analysis of the type of person who patronized an American-style dairy-lunch counter with it’s bland American food, low prices and antiseptic environment and how their taste in food and choice of restaurant would inform all of their cultural taste. It’s not fair to have singled out pie from the large menu of boring American food — that realm of dishes now known as American comfort food — but pie was the common dessert and seems like an innocuous dish. It was the beginning of a critique of American middle-brow culture.

What’s next for Ben Katchor?

I’m writing and drawing a long comic-strip to expand the collected Hotel & Farm weekly comic-strip series into a book.

Mark Newgarden is a cartoonist and co-author (with Paul Karasik) of the Eisner-winning How To Read Nancy. He lives in Brooklyn and teaches at the Parsons School of Design in Manhattan.