LEW SAYRE SCHWARTZ: You were the first to do the adventure continuity.

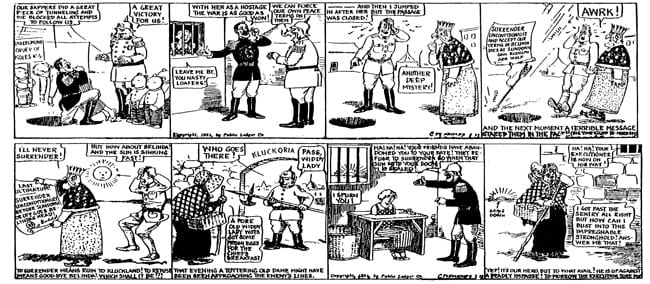

ROY CRANE: Well, I think so. It largely depends on what you call “adventure.” C.W. Kahles, who did Hairbreadth Harry — she [his wife] has been very eager to establish her husband as being one of the very greats, and with reason. He had the misfortune to be about the second or third along who would do certain things. Well, I always thought of it as being a satire on the old, melodramatic plays of the earlier 1900s. And I read an article in which he was quoted as saying it was satire.

And in 1924, soon after I went to NEA, there were also all the people there, who were trying to figure out what the hell it [Wash Tubbs] should be. And Landon’s first thought was, let’s give him a background: He works in a grocery store. Well, that made George Swanson mad because Swan had a strip, Salesman Sam. What were the gags to be like? Were they going to be joke things or would it be stuff sort of like DeBeck had. They had little twists on the end, but they weren’t exactly jokes. Or there was The Gumps, that was going very big. He had a bunch of wisecracks all through the thing. And everybody had a different idea. And I didn’t pretend to know anything about comic strips, and for a while I went along with this, and then the president of the syndicate had a brainstorm. I guess he would have called it that. He figured out that everybody liked the movies. Why not make a strip about the movies? There was no other strip about the movies. So they sent me to New York, and I think I spent about two, at the most three, days at the movie studio. Watching them make a picture. And that was supposedly to give me enough background so that I could do a strip about the movies. Well, I didn’t like that worth a damn. I was being pushed around and so forth, and I wasn’t good at getting jokes. This was the day of the jokes. He-She jokes kinda thing. Or the Mutt and Jeff He-plus-He jokes. And the cartoonists were stealing them right and left. A joke would come out — hell, they’d change it very slightly and use it. And it was so bad that on The Cleveland Press, one day the same joke appeared in two strips and the next day it appeared in a third strip. That’s how bad it was.

And I tried to do more or less original stuff, but I would sit there and listen to the old New York Central trains go by and, out in the distance, it’d be the ships coming in, [makes sound of ship foghorn] whistling and, oh boy, I wished that I was out of there. I did not like that at all, being muscled around by everybody in the place, telling me what to do. And I thought, I wanted to do a story, an adventuresome story, take Wash to the South Seas. That’s where I wished that I could be at that time, and well, I told him about it, and he said, “Well, OK, provided you bring in these movie people at the end and they save the day.” I think Wash was with a bunch of cannibals or something, so I had to bring those damn movie people in. Fortunately, by the time that I finished the story, which was a very, very poor adventure story, it was mainly continuity. There was a villain named Tomalio, I think his name was. He used to sharpen his knife and glare at Wash. Then he threw him overboard. And I pulled my first really big boo-boo: I had Wash thrown overboard in shirtsleeves; the next day he was floating out at sea and he had his coat on. I don’t know how that happened. [Schwartz laughs.] Well anyway, it’s about time I finish this little story. The head of the company was no longer there, so we dropped it after the movie people came in, we dropped it very shortly after that. And I didn’t do a good job on that adventure story thing.

After the crash in ’29, within a couple of years the papers were feeling the pinch, and they were wanting to drop comics, and they were wondering which ones were the ones to drop. And when they dropped the adventure strips, people squawked like heck, because they wanted to know what was going to happen next. And it was a great surprise to most everybody, including the editors and publishers of papers. And they would take polls, and heck, I’d be right there on the top almost. The good panel things would generally come in first, because there wasn’t much reading and the person would get it in just a flash, but we were running ahead of the joke strips and the like. And of course the joke strips were being dropped right and left, and syndicates then wanted nothing but adventure stuff. Well, it didn’t have to be an adventure story, a knock-down drag-out fight sort of a thing. There are other kinds of stories. “Well, we want adventure!”

So much so that... Merrill Blosser who does Freckles, Freckles and [His] Friends; it was a cute little kids’ strip at that time. And we went out to California and saw him, quite a bit of him. We went out there two different years; I think it happened in between the two years. He was told by Ferguson to age him 10 years, overnight, and send him out on an adventure. And Blosser did. He’s a very methodical worker — I used to envy him for that — and he would pick up a strip a week, so that at the end of the year, he could take a nice vacation. And this was about the summertime and he was all ready for a plan to vacation up in Oregon for a month and he said, “Well, now, I would like to get in a vacation first.”

And Ferguson: “Start the thing now! Now! Tomorrow!” And by God, he had to start it tomorrow, and he aged him 10 years overnight and he sent Freckles on a safari in the darkest Africa. And that’s the way things were going. Some of the joke strips tried to convert.

SCHWARTZ: Let me ask you a question, because it’s gone full cycle again, as you know.

CRANE: Yeah, yeah.

SCHWARTZ: And I was curious; I was going to ask you what you thought was the reason that the circle has been completed, 360 degrees, and we’re back to the joke strip. I would assume, and you can comment on it for me, size and the television too, obviously the squeezing down of the comic, the dimensions of the television screen, are given as reasons for this decline in the adventure strip. And it’s probably quite true. But what are your feelings about this?

CRANE: Well, I feel that continuity strips, at least my strip, Buz Sawyer, which I started during the war, that adventure strips were never stronger than they were during the war. And that certainly goes for [Milton] Caniff, who had his stories tied together and he got quite a lot of impact out of it. But now, the jokes that came after the war, the types of gags that were used in The New Yorker, changed the type of humor.

SCHWARTZ: It became more sophisticated.

CRANE: Yes. And, Chic Young certainly came out with a different way of telling a story, then. He would have his maybe four pictures and the third one would be his gag thing, and then in the fourth picture, he would give the reaction of the people, which is in [John] Gallishaw’s book on how to write a short story. Now that was picked up by a lot of people. I did it in Sunday pages and the like, where you maybe had humor and everybody else did.

SCHWARTZ: That’s interesting.

CRANE: So he told jokes that were completely different there. Much fresher-sounding, and they’re built around character, too. More strongly on character than ever before. So it may have been that this cycle would have snaked around anyway, but in this wartime period, the price of newsprint went to hell and gone. And a long time, we were turning out five-and six-column comics, I guess. Anyway, it wasn’t long after that that they cut the comics down to four columns, that was about eight inches wide, and when they did that, you just couldn’t put in four pictures very well. And well, I saw that immediately we would have to go to three. And it wasn’t long before everybody, I don’t know that they did it because of my doing it, but they probably found out for themselves that they couldn’t put all that in four pictures. Now that made this difference in a story that would run 12 weeks. You had, I think, it’s 72 fewer pictures in which to tell a story. That meant that you left out something in there. Either you had to leave out the character-building or you had to leave out the blood-and-thunder adventure stuff. And at the same time, a reader wasn’t getting as much as he did before. The readers began to squawk. Well, the stories dragged. So the editors, the publishers, they would jump on the cartoonist to liven them up, shorter stories. Shorter stories wasn’t the complete answer. You just didn’t make the impact on a reader with three pictures in a strip as you would with four.