From The Comics Journal #148 (February 1992)

In this 1992 interview, Charles Burns and Darcy Sullivan discuss teenagers, critics, his work in Europe and the art of psychological horror.

At the juncture of fiction and memory, of cheap thrills and horror, lies the dark world of Charles Burns’ art. His stories, appearing in alternative comics such as Raw since the early 1980s, take comic book clichés — wiseacre kids, sinister scientists and tough-as-nails detectives — and rearrange them into disturbing yet funny patterns. Beneath this interplay of familiar iconography lurks the real traumas of childhood, traumas of loss and alienation. Similarly, Burns’ ice-cold artwork polishes a “conventional” comics look to the nth degree, underlining the artificiality of what we take for normal. At times, Burns’ work suggests that our worst fears about mainstream comics are true: that they are stamped out by machines programmed by someone who is slowly going insane. Recently, Burns has branched out, becoming one of independent comics’ most notable writer/artists. He helped design a ballet based on The Nutcracker, did a cover for Time and produced a nightmarish cover for Iggy Pop’s album Brick By Brick. He has also steered his unusual weekly comic strip into new markets, exposing hordes of unsuspecting readers to the joys of demented deities, inadvertent sex-change operations and dead kids who won’t stay dead. Charles Burns lives in Philadelphia with his wife, painter Susan Moore, and their two young daughters. It’s a cliché, but Burns does seem jovial and down-to-earth, not at all the lost soul his stories might suggest. At the same time, he shies away from deconstructing his art; as he makes clear, he would prefer that readers delve beneath his work’s seductive surface alone. — DARCY SULLIVAN

THE IMPRESSIONABLE YOUTH

DARCY SULLIVAN: You were born in Washington, D.C. Wasn’t your dad a serviceman?

CHARLES BURNS: He was an oceanographer, working for the government. I can’t describe much about his job.

SULLIVAN: Did you move around much?

BURNS: Yeah … I spent a majority of time growing up in Seattle. Before that, I lived in Boulder, Colorado, Maryland and Missouri.

SULLIVAN: How old were you when you settled in Seattle?

BURNS: Fifth grade, I guess. Somewhere around 1965.

SULLIVAN: What kind of place was Seattle to grow up in?

BURNS: Well, I was lucky enough to have kind of a nice neighborhood with woods around. I wasn’t living downtown — suburbs isn’t the right word, but it was the nice part of town.

SULLIVAN: Did your Mom work, too?

BURNS: No, she didn’t.

SULLIVAN: Did you have brothers and sisters?

BURNS: I have one older sister, three years older than me.

SULLIVAN: When did you get interested in comics?

BURNS: As far back as I can remember. Before I could read; I just liked picking up stuff. My father also had an interest in them, and would bring back books from the library, anthologies of Pogo and Li’l Abner, that kind of stuff. I would look at them and somehow they struck a chord. He had the paperback anthologies of the early Kurtzman Mad, so that had an effect on me. Also, very early on, I had very early American editions of Herge’s Tintin. They must have been fairly obscure, because I don’t hear too many people talking about them.

SULLIVAN: Were your parents pretty encouraging of your reading that type of thing; did they mind at all?

BURNS: They weren’t encouraging, but they weren’t discouraging. I would be able to look at stuff that I wanted to, for the most part, and not have it thought of as trash that should be thrown out. I mean, I had friends who, if a comic book was in the house, it got thrown out. The backlash from the ’50s was still present. And I remember my father kind of checking out what I was bringing home. But there wasn’t really much that you could buy that was deviant.

SULLIVAN: Were there any kinds of comics they frowned on?

BURNS: Later on, in the early ’60s, I picked up the old monster magazines. They didn’t frown on them, but they were like, “Ecch, maybe you have too many of these.” It wasn’t any big deal. If they were concerned, they didn’t make it that clear to me. I could pretty much get what I wanted to.

SULLIVAN: What type of stuff were you buying?

BURNS: By the time I started buying stuff myself, it was just the normal fare. Mad magazine and superhero stuff like Batman and whatever was out there. I would look for anything that looked cool. And at the time, there wasn’t that much.

SULLIVAN: Did you read Creepy and Eerie?

BURNS: Yeah, later I read that stuff, too. I think I had one issue of Creepy or something like that torn up, but that was the extent of it. “I don’t want you reading this garbage!”

SULLIVAN: How about the schlocky reprint books that were often quite gory? Like Weird?

SULLIVAN: How about the schlocky reprint books that were often quite gory? Like Weird?

BURNS: I had friends who bought those, but I was kind of repelled by those. Now I find some occasionally and I can enjoy them for whatever they are, but back then I thought my friends didn’t have any taste. You know, “This isn’t the good stuff.”

SULLIVAN: Did you have an appreciation of artists at that time?

BURNS: Oh, yeah; absolutely. There was a look, a style of artwork that I liked. The things that affected me the most were the reprints in Mad. They really blew me away — looking at Bill Elder’s stuff and how everything was thrown in deep shadow, how it was put together. There was, for me, this very creepy atmosphere. You look at it now and it’s lighthearted and funny, but back then it seemed kind of creepy. I always liked the atmosphere of it. In a way, you get affected more by the atmosphere of [Elder’s] strips than by the way he drew a face or anything like that.

SULLIVAN: Were there superhero artists that you enjoyed?

BURNS: I wasn’t so aware of that. I always liked the kind of bad Bob Kane Batman — the shading and the shadowy characters. I always liked the cartoony stuff rather than the more serious, more realistic look.

SULLIVAN: How about artists in the newspaper strips?

BURNS: I don’t remember being affected that much. I really liked Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy. That was one of the few strips that really stood out.

SULLIVAN: Were you a big monster fan when you were growing up?

BURNS: Oh, yeah. In the early ’60s, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth was putting out models, and there was Famous Monsters of Filmland and stuff on television. That fad came at just the right time for me. I loved all that stuff.

SULLIVAN: Did you read Famous Monsters?

BURNS: Yeah; didn’t sit and read it. I looked at the pictures and got creeped out.

SULLIVAN: Did it scare you?

BURNS: Some of it really did. I was in second grade — just young enough to get really spooked by it. There was this one article on [Roger Corman’s 1961 film] The Pit and the Pendulum, and this torture device really freaked me out. It was the fact that it could cut somebody. I remember not being able to look at that particular photograph. I’m still like that; there are still things that freak me out.

SULLIVAN: Did you watch a lot of horror movies on TV?

BURNS: Yeah, yeah. I watched The Outer Limits, which was really good. And in Maryland there was a show that would have a bad horror movie each week; a Giant Gila Monster one night, and The Amazing Colossal Man the next.

SULLIVAN: Were you scared by one type of situation or thing more than another?

BURNS: Psychological horror got to me. There was one particular movie that made me leave the room. It was a bad William Castle movie called The Tingler [1959]. There was this one scene where this man injected his wife with something — he’s trying to scare her to death. She’s a mute, and she can’t scream; she’ll die, or something. There’s a scene where he runs into the room like a maniac with an axe, and she runs to the bathroom. She turns around and there’s a bathtub full of blood and a hand starts coming out of the bathtub. I had to leave the room. It was getting worse and worse. [Laughter.]

It was more what you didn’t see, more what you were imagining. If there was some monster, that was fun; no problem there. But if it was some sort of psychological situation …

SULLIVAN: Were you able to share your interests in horror and comics with other kids?

BURNS: To a certain extent. I remember later on kind of forcing friends to sit down and draw, to get involved in the stuff that I was interested in, forcing them to make their own comics, too. I was always much more obsessed with all that stuff than anybody I was around.

SULLIVAN: When did you start drawing?

BURNS: Day one. It was one of the things that I could do fairly well, so I pursued it. I wasn’t great at sports, I didn’t have a flamboyant personality, but I could draw.

SULLIVAN: All your stories seem to portray adolescence and being a teenager as rough years.

BURNS: I never got over it. [Laughter.]

SULLIVAN: Was that a rough time for you?

BURNS: High school was kind of deadly for me. I think it was deadly for a lot of kids. Going to school was like a trap.

SULLIVAN: Were you a good or bad kid in high school?

BURNS: I was kind of a good bad kid; I skipped out occasionally, but I was a very average student. I’d slide by.

SULLIVAN: Did you have art classes in high school?

BURNS: Yeah. There were always ways of getting through the day. Projects where I could get out of class, like painting murals.

SULLIVAN: Were you socially adept in high school?

BURNS: I wasn’t a total nerd, but I wasn’t a big, socially popular kid.

SULLIVAN: Were you dating?

BURNS: Oh, yeah.

SULLIVAN: It always looks so dangerous in your comics, the date during high school.

BURNS: Yeah, it’s hard to explain all that stuff. I don’t know where it comes from. I guess I’ve always liked real-life horror. I can’t help thinking about that kind of stuff.

COLLEGE DAYS

SULLIVAN: Tell me about how you ended up at Evergreen College.

BURNS: It was the same kind of a backlash [I felt in] high school: knowing that I was supposed to go to college, but not sure what I wanted to do. I was taking fine art classes at the University of Washington, at Central Washington State College, over in Ellensberg, WA. And then the last year I was in undergraduate school I finished everything up at Evergreen in 1977, because I had friends going there and I had taken a photo class there.

SULLIVAN: Was Evergreen a progressive school?

BURNS: It didn’t have a grading system. It was pass/fail. You took whatever classes you wanted and if you got enough credits, then you graduated. That’s one of the reasons I graduated.

SULLIVAN: Did you meet Matt Groening and Lynda Barry at Evergreen?

BURNS: Yeah. Groening was working at a paper there called the Cooper Point Journal, and my second semester there he was the editor. I’d bring in comic strips, and I think the second semester I did paste-up for ads and stuff like that. Lynda was a gallery director there, and I had a show there with a couple of friends.

SULLIVAN: What kind of comic strips were you doing then?

BURNS: There were a couple of short-lived, kind of science-fictiony … I don’t know how to explain them. Some girl gets kidnapped by these little mutants, or something stupid. They really didn’t get off the ground. The strips that I did after that tended to be a bit more conceptual. I had one called “Pornographic Computer Romances,” just pictures of computers moaning and groaning. Real stupid stuff.

SULLIVAN: Were you interested in the writing, too, or were you mainly approaching comics from a graphic standpoint?

BURNS: Initially it was from a graphic standpoint, but fairly early on, there were ideas that I wanted to get out, stories that I was interested in. I was always an artist first, and then I worked at being a writer. Writing is still hard. It’s always hard.

SULLIVAN: Were you still interested in comics in college?

BURNS: I wasn’t looking at too many comics then. I wasn’t reading superhero comics or buying stuff actively. Maybe the occasional underground that was still floating around. I was more interested in things like photography.

SULLIVAN: Whose work did you admire in photography?

BURNS: People like Les Krims. Diane Arbus, Gary Wino-grand. There were a lot of people I liked.

SULLIVAN: Were you taking a lot of photos yourself?

BURNS: Yeah. They had a great darkroom setup at Evergreen, so I was shooting and printing stuff pretty regularly. Even my photographs had some narrative concept. I did a series of photographs that in a way mimicked panels of comic strips. Even though they were obscure, they still had a feel reminiscent of grouping a whole bunch of images together on a page.

SULLIVAN: You mentioned the undergrounds. Were you reading them when they came out?

BURNS: Oh, yeah. As far as the sequence is concerned, I read all the superhero stuff in grade school, and it probably spilled over a bit into junior high. But somewhere in junior high, I started seeing all the underground stuff coming out of San Francisco, [my reaction was] “This is what I’ve been waiting for.” I wanted to like comics, but I was really pretty bored with them. Then suddenly it was like, “Ah, this is what comics should be.” It was really great stuff.

SULLIVAN: Which artists had an effect on you?

BURNS: The person who had the greatest effect, of course, would have to be Robert Crumb. His stuff is incredible. Kim Deitch’s work I liked a lot. The S. Clay Wilson stuff I wanted to like but it was too horrific. “Oh, God, what if my parents found this?” There wasn’t the concept of being politically correct back then, but that was how I felt; “What’s my girlfriend going to say if she thinks I like ‘Captain Pissgums’?”

SULLIVAN: Can you remember any of Crumb’s work that you particularly enjoyed, or that really stuck with you?

BURNS: Well, all of it. I would pick up everything he did. I remember a friend telling me, “Hey, there’s a new comic by Crumb called Big Ass!” I went, “Oh, God, I guess that means I have to buy a comic called Big Ass.” In retrospect I know that I was also very influenced by all the psychedelic stuff, like Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso. Now that they’re not doing comics, it seems like they had a lesser impact. But I know that I was doing fake psychedelic stuff and fake Crumb stuff, kind of merging it all together. For this literary magazine in high school I did this thing called “Handy Comics,” with psychedelic lettering inside of this little hand. Everything in it was ripped off of Robert Crumb or Rick Griffin or somebody.

SULLIVAN: Did you like Richard Corben?

BURNS: I was always a little hesitant about his stuff. It took itself a little too seriously. Robert Crumb had his obsessions, but I guess I can buy into them a little more than the big muscle guy and the woman with the big tits and that whole thing.

SULLIVAN: One comics group we haven’t talked about is ECs. Were you starting to discover those?

BURNS: Yeah. They did some reprints in underground comic form, but that was much later. I had seen a couple of paperbacks. They were a little too hardcore when I was younger. But much later I picked up on all that stuff.

SULLIVAN: Of the EC artists, the one that comes to mind when I think of your work is Al Feldstein.

BURNS: Yeah, Feldstein and Johnny Craig I liked. I also liked some of the drier artists like George Evans and Reed Crandall.

SULLIVAN: What else was having an influence on your art style at this time?

BURNS: I would pick up on one little bit of this and one little bit of that. I could say pop art had an influence on me, and it did. But it’s always hard for me to talk about influences in the sense that I can’t point to some specific thing. It’s whatever I bumped up against.

SULLIVAN: I read somewhere that Japanese woodblocks influenced you …

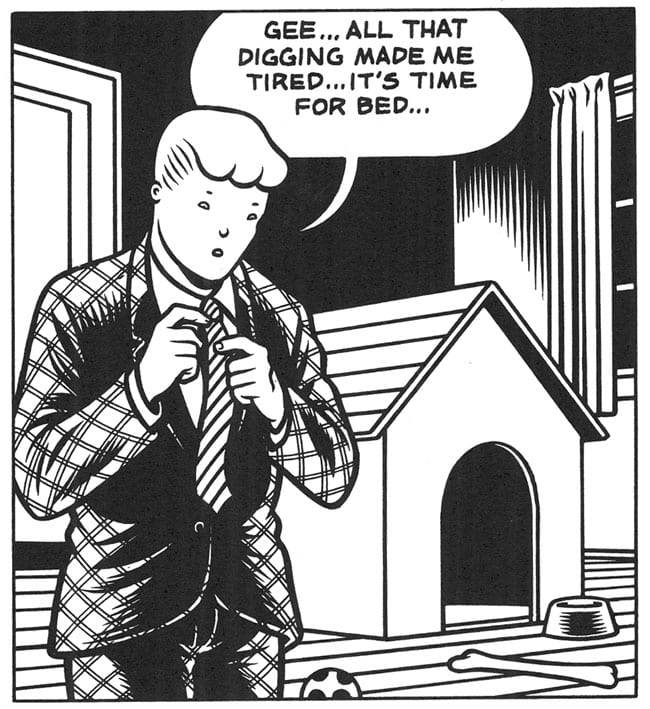

BURNS: I’d always liked the look of Japanese woodblocks, and in a college course in printmaking, I learned how to do the traditional method of woodblock printing. Some earlier comics of mine have that crude Japanese perspective with no vanishing points, and Japanese-type characters. Some of it has carried over into a few characters, like Big Baby, who has a big round white face and tiny little features. Recently, my characters have bigger features, but if you look back at earlier strips of mine, they almost always had teeny tiny little features, like Dog Boy.

SULLIVAN: When you graduated in ’77, did you have an idea of what you wanted to do?

BURNS: Not at all. I went to graduate school in Davis, California for two years and did painting and sculpture. I wasn’t really ready for the real world. I was given a studio, and did stuff that I knew I’d never have the chance to do again. I did bad conceptual videos, music, and photography. I did a photo comic that’s going to see print one of these days. It’s supposed to be in an upcoming issue of Taboo. It was the first longer story I’d done. I’d always done bits and pieces of things. This is 20 or 25 pages. That photo comic led me to believe that I could do longer stories, and the story after that was “Ill Bred,” which finally saw print in Kitchen Sink’s Death Rattle. I did it in ’79, and I don’t think it was published until ’85.

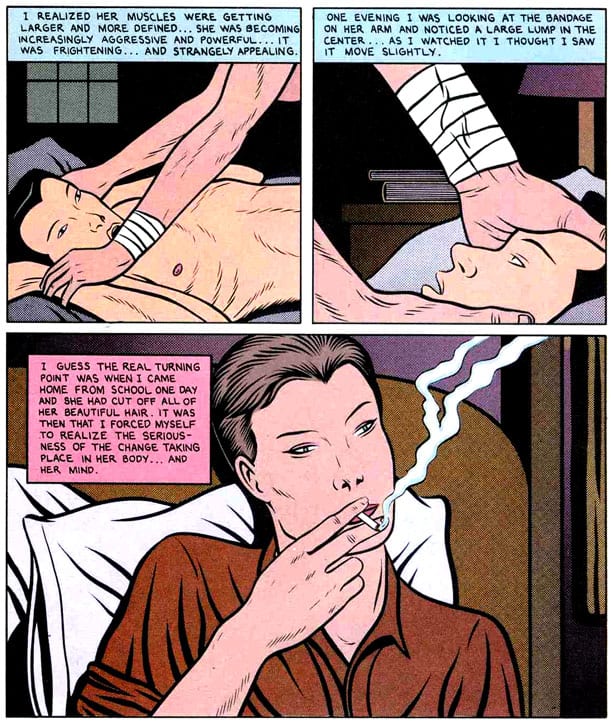

SULLIVAN: “Ill Bred” already displays a lot of the themes you’ve carried on through your work: transformation and invasion, with a sexual motif. After the woman in the story is infected by this insect she seems very masculine, and the man becomes more feminine …

BURNS: Yeah … wow! [Laughter.]

SULLIVAN: It seems to be the straightest horror story you’ve done. There’s not so much irony to it.

SULLIVAN: It seems to be the straightest horror story you’ve done. There’s not so much irony to it.

BURNS: Yeah, that was like getting a story out of my system. There are things that come back again and again until I tell myself, “Oh no, you can’t tell another story about severed heads.”

SULLIVAN: Were you working your way through grad school at the time?

BURNS: Sort of. Little bit of everything.

SULLIVAN: Were you getting art jobs?

BURNS: No, not really, just struggling through.

When I was in school I was doing things that would fit into the idea of fine art. You created an object, and that was supposed to be something you would sell through a gallery or sell yourself, and it would be put in a frame or on someone’s wall, and that was it. And by the time I graduated, I had decided that wasn’t for me. I wanted to do something that was more accessible, and I had always liked print media. I made a choice to pursue comics. I didn’t have a game plan, like “I’m going to submit this to this particular magazine.” I was trying to send stuff to Last Gasp and places like that, but it was the end of the success of underground comics. They were starting to have pretty rough times.

SULLIVAN: Did you shop your portfolio around to art directors?

BURNS: Eventually I did, yeah. I moved out here to Philadelphia — I’ve moved around since then a lot — and I was waiting tables, being a busboy, and then coming home and trying to do comics. I would take stuff around Philadelphia, take portfolios around New York City, but I was an unpublished illustrator. Occasionally, someone would say, “This stuff is pretty good but it’s really weird, uh, come back later.” It was that Catch-22, where to get published you have to have something published. And it’s really true, if you’re an art director you are very rarely going to take a chance on someone who hasn’t been tested.

SULLIVAN: So how did you get tested?

BURNS: I slowly had a few bites here, a few bites there. A big job was this nursing magazine — I did a cover and these little interior illustrations, like I was on my way to the big time. It was a rough go.

SULLIVAN: What was the turning point?

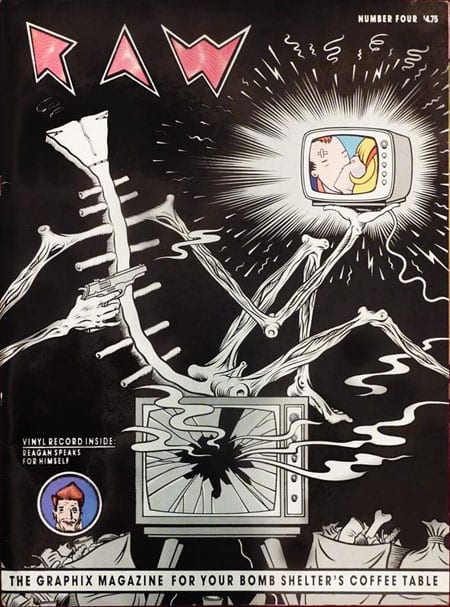

BURNS: Getting in Raw magazine. It was like my work was getting taken seriously by somebody.

SULLIVAN: Had you done other work for comics magazines at that point?

BURNS: I was sending a full-page strip to a place in Oakland, California. It was a punk thing, one of those free advertising papers, called Another Room. And I think I brought stuff into Heavy Metal, and they were encouraging, but it was mainly illustration pieces. I still didn’t have the idea that you bring in a finished comic and try to sell that. I was saying, “Do you like my work?” Which didn’t really work that well. I found that out.

SULLIVAN: So how did you make the connection with Raw?

BURNS: The first issue said, “We’re interested in submissions” and that’s what I did. One of the few cases where someone was “found” through submissions. I set up an interview, and Art Spiegelman looked through all my stuff and said, “This is pretty good.”

SULLIVAN: Did you like Raw when you saw it?

BURNS: Yeah. My initial reaction was that I really liked the size. I liked looking at comics that weren’t necessarily narrative, but that you could just enjoy looking at, like ink on paper, and I liked the large format. I didn’t like everything that was in there, but I liked what it was.

SULLIVAN: After you had the interview and he was encouraging, how did it proceed from there?

BURNS: I went ahead and made a piece specifically for the magazine, more non-narrative stuff. And one of the strips I was sending to this place in California was the first Dog Boy strip. I was about to send it out, and Art said, “I want this.” I said, “OK, you’ve got it.”

SULLIVAN: What kind of direction or encouragement did you get from Art?

BURNS: It was from both Art and Francoise Mouly. In those days Francoise was much more involved directly with the editing. It was just having someone who could critique your work well. Someone whose opinion I would trust. Not big editorial comments: “I don’t like this guy’s forehead” or “I don’t like the way this hand is drawn,” but more how the stories were structured. That was very beneficial for me, that very constructive criticism.

The best kind of criticism is stuff that you know subconsciously already, and then someone that you trust reconfirms your worst fears. Occasionally I’ll draw something and I’ll show it to my wife or somebody, and say, “This is OK, isn’t it?” “Nah, it’s not really OK.” “Aw shit.” I already knew it wasn’t working, but I had to have that confirmed by someone else.

SULLIVAN: Did you go into the Raw office and meet the other artists?

BURNS: At that point, it was just Art and Francoise’s living area — one sprawling room with a few dividers, a big cavelike structure. Somebody was always there working, it seemed like, or somebody was coming over. When I was going to go up to New York, maybe Gary Panter would be in town, and I’d meet him, and Mark Beyer, whoever was around. It seemed like there was always a flow of people, tempers flaring, on edge. There was always this flurry of activity.

SULLIVAN: Did you get involved in projects, like the tearing of the covers?

BURNS: Not very much. I was involved with the die-cut cover [#4], trying to figure out how to do it. No, I never bagged any bubble gum. I was not a New Yorker and wasn’t there on call.

SULLIVAN: What other markets were you breaking into at the same time? You did get into Heavy Metal. When did that take place?

SULLIVAN: What other markets were you breaking into at the same time? You did get into Heavy Metal. When did that take place?

BURNS: Around 1982 or ’83. It didn’t pay great, but it paid, so that was nice. The El Borbah strips were serialized in there, and at that point I was starting to take the strips that appeared in Raw and sell them in European markets. That was where my other income was coming from. But it was a trickle, it was very, very gradual. I was trying to get a strip in The Village Voice, and I had a little one-panel strip that appeared in the The Rocket [a Seattle-based rock tabloid] for awhile. A couple of them got reprinted in that “Raw Gagz” [#8]. They were dumb one-shot gag cartoons. I wasn’t very comfortable with that, to tell the truth. I had made up a bunch of samples, and I was supposed to get this space on the back of The Village Voice, because supposedly whoever was doing that was going to be booted out or something. There was something weird there. I was talking to the editor about it, and he was encouraging, but I was never very happy with what I had come up with.

At that point Art Spiegelman was working for Playboy, and that was really big bucks. I remember trying to create a one-page strip for Playboy. It was kind of a romance throwback. I just never could get it. Art was trying to help me: “You’ve just gotta think about what Hugh would like.” And I never could figure out what Hugh would like. My stuff was still much too weird for them. I had a strip called “I Married a Maniac,” about some woman who’s chained to the bedpost, and she’s washing dishes. Their response was, “Uh, Charles, you’re not quite getting it. The guys who’re reading Playboy don’t want to think of themselves as sexist pigs. They’re not going to think that’s too funny.”

SULLIVAN: You were critiquing the Playboy ideal.

BURNS: Yeah. Then I was trying to throw in this sexy humor, but I just could not get with it. It was really lame.

SULLIVAN: Lots of big, buxom gals, though?

BURNS: Well … I was too embarrassed. I ended up doing stupid stuff. A woman comes home and her husband’s in a giant bunny outfit, and he says, “Come on, honey, can’t you get in the mood?” Just real stupid.

SULLIVAN: How did Art feel about working for Playboy and trying to meet that Playboy ethic?

BURNS: He was doing it for the money. It was one of the games in town. He was smart enough to figure out how to play by their rules, and did it. I think it was fairly painless for him. But it was pretty painful for me.

SULLIVAN: Were you able to support yourself through the comics work?

BURNS: Like I said, I was struggling. I was taking the subway to work, as a waiter and busboy. And it just eventually got better. I started selling things in Europe, and it picked up slowly.

SULLIVAN: When Raw went to the digest size with Penguin a lot of people had the attitude that it had sold out. How did you feel about that backlash?

BURNS: I don’t know, there are pros and cons of the different formats. I tend to like the big graphic size myself. On the other hand, I also like reading a whole bunch of good stories, which you can’t do in the large format.

SULLIVAN: Did the pay change at all when it went to that size?

BURNS: Raw was never like a paying job. I never thought of it that way. When it was just starting out, Art and Francoise would sell their issues, and when everything was sold out, like a year later, they would get all the profits together and divide them up. But I never thought, “Oh, I’m going to be raking in the bucks now.”

SULLIVAN: How did Heavy Metal pay?

BURNS: I think it was $150 a page or something like that.

SULLIVAN: And did the Europeans pay OK?

BURNS: It depended on the magazine. Generally, they’d try to pay you as little as they can. But if they want your work enough, then you can negotiate.

DOING ITALY WITH VALVOLINE

SULLIVAN: How did you get hooked up with the European markets?

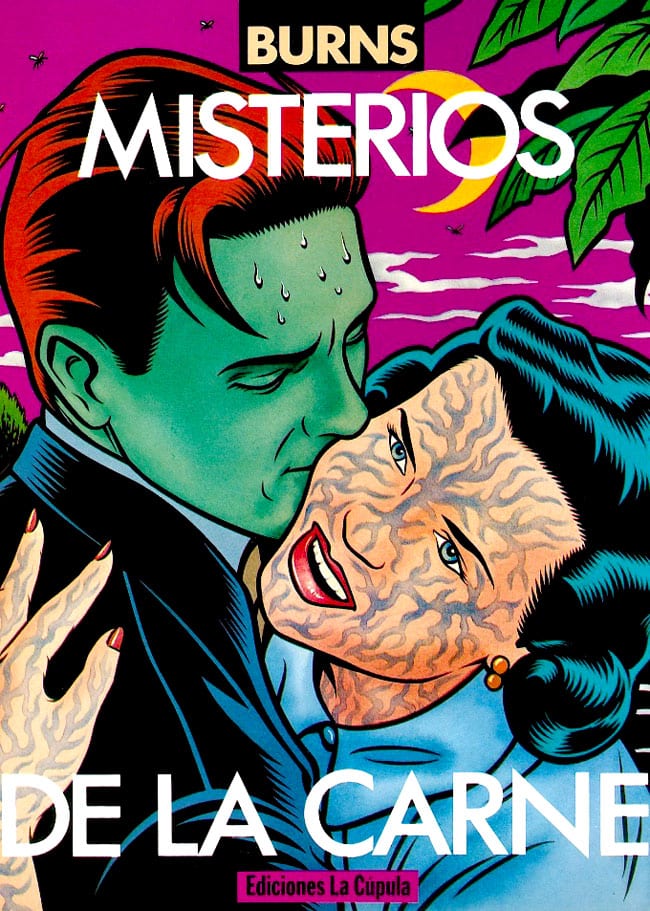

BURNS: A lot of people were in and out of New York, and they were seeing stuff in Raw magazine. The first person I got hooked up with was Josep Maria Berenguer, who started El Víbora in Spain. It was a pretty wild magazine. Lot of Spanish stuff, but they imported a lot of stuff, too. They’ve printed just about everything I’ve ever done. They put out a Spanish book of my work called Misterios de la Carne, “Mysteries of the Flesh.”

SULLIVAN: You lived in Rome for awhile. Was it because of the work you were getting out of the European market?

SULLIVAN: You lived in Rome for awhile. Was it because of the work you were getting out of the European market?

BURNS: Not exactly. My wife teaches painting, and a program over there invited her over. We had visited Italy before, and I had met some of the comic artists there. I was getting stuff published over there as well. So when this opportunity came up, we snagged it, and moved over there for two years, around 1984 or ’85, up until 1986. I’m not sure. I’m bad at dates and names.

I was doing some illustration and some comic art there. Right when I got there I was doing something for a German magazine. I got involved with a bunch of Italian artists and got invited into their comics group, Valvoline. They were a group of young cartoonists who were friends and associates, and they would put together sections in anthology-type comics. They would be given, say, 30 pages per issue, and they would edit that section, it would be the Valvoline section. If someone in the group would not normally have been published by that magazine, because the publisher or editor didn’t like their work, Valvoline would be able to dictate that it was good, and [they wanted it] published. And there were other things that came up; they did art shows, portfolio silkscreen prints, and I’d be involved with those. I don’t know if you’ve seen Mattotti’s fashion illustration stuff, but I was working for the same magazine doing some fashion illustration, believe it or not. It wasn’t totally straight, it was kind of cartoony. It was like what I do, except I guess the actual clothing was a little bit straighter. I’d have women on Mars and aliens and robots and flowers — you name it. They would send me photographs and slides of models modeling the clothes, and I’d work with those.

SULLIVAN: How many artists were in the Valvoline group?

BURNS: Probably six or seven. Mattotti was involved, and Massimo Mattioli, who did Squeak the Mouse. There was Igort — Catalan’s reprinted one of his books — Daniel Broli, Giorgio Carpenteri.

SULLIVAN: Did they see themselves as having shared ideals or goals, or artistic similarities?

BURNS: They had artistic similarities. They were fairly diverse, but they had wider interests than the typical comic creep attitude of, “I like comics; I know what I like.” They were interested in literature and film and music and art. A lot of them were interested in Italian futurist artwork.

SULLIVAN: Did they have any political bent at all?

BURNS: It was mainly artistic. It’s hard … you’re talking about a severe language barrier, as far as I’m concerned. I never really figured out Italian. I could sit there and grunt and groan enough and make myself understood, but I wasn’t conversational.

SULLIVAN: How would you compare Valvoline with, say, the Raw group?

BURNS: I don’t think there was that same kind of identity at Raw. Valvoline was a much more cohesive group; they were friends, they had been together quite awhile, and they all came up around the same time. They shared interests and were discovering working with different materials, like Mattotti was starting to work with oil pastels. I think the artists in Raw magazine have an identity, but it’s not the kind where you’re all sitting in a room and deciding something simultaneously. It’s like being unified by being in the same magazine.

SULLIVAN: This group sounds pretty different from anything we have here.

BURNS: I think it might be similar to the early underground cartoonists. There was a sense of community in San Francisco, people discovering each other, discovering they had similar interests, and trying something new.

SULLIVAN: Were there a lot of Italian groups like Valvoline?

BURNS: It sounds like a comics club. [Laughter.] No, not really, it was a novelty. They were unique in the sense that they were creating their own niche. Or trying to. Since then, they’ve kind of broken off and gone their separate ways. I’m sure they’re still friends to varying degrees, but back then they were all centered in Bologna and within a short walk of each other’s houses. By the time I was there, it was already starting to be not quite as intense as previously.

SULLIVAN: Was there a leader or guiding force behind it?

BURNS: Mattotti would probably be the person, because he was the most serious, in the sense that he worked like a dog. He was very focused and very, very serious, and you can really see that: out of all those people, he’s the one that’s most visible now. Well, Mattioli was doing Squeak the Mouse, but I haven’t seen anything by him for years now.

SULLIVAN: Did you enjoy that sense of community?

BURNS: It was really nice for me, because I wasn’t an American hanging around with American friends. It was like being included and immersed in Italian culture, so it was really fun that way. And they organized a Valvoline show in Switzerland, and we all took the train up. Painting a whole room, videotaping everything, some of them were playing in a group, so the music was going on … it was fun.

SULLIVAN: What type of publications did Valvoline work for?

BURNS: I think there were a few miscellaneous early publications that I can’t remember. The first one I recall was a magazine called Alter Alter. When I got to Italy I did one of their Valvoline sections. And later on we did a few things for Frigidaire magazine. That was the magazine that Liberatore, the guy who did Ranxerox, came out of. That was its claim to fame. It was a very hardcore, left-wing comic magazine based in Rome — real notorious, always getting busted. It was hell to get paid from them, but anyway … Right after I left, Valvoline essentially created their own magazine called Dolce Vita. That lasted for maybe two years. I had a bunch of stuff published in there. It was an oversized magazine like Interview. It wasn’t just comics, it was popular media, music, film, whatever. And then most recently, there’s some other magazine, I can’t even remember the name of it … but I haven’t heard from them recently, so it’s probably gone down the toilet, too.

SULLIVAN: Was there a different sense about comics there, or about Valvoline’s position as comic artists?

BURNS: It’s hard to say, because Valvoline’s image was “young comic artists with an attitude.” They weren’t the big fan artists. There were people that everyone loved, like Liberatore. He was really admired, but these guys were too experimental and too wacked out to be that popular. It’s somewhat similar to the way it is over here.

THE TERROR OF JACKSONVILLE

SULLIVAN: When did you start your newspaper strip?

BURNS: It was after I came back from Rome … ’87, maybe? I gave a lecture in Baltimore at a show of Raw artists. While I was there a couple of editor/publishers said to me, “Hey, do a weekly comic strip.” One was from a Baltimore paper, and he was going to move to New York City. The other had three papers and was based in Denver. They were very enthusiastic and it was something I hadn’t considered before, because of what a weekly strip is. I like doing stories that are longer and have more complex narratives, instead of a gag a week.

Eventually, I decided that I would just try it. I liked the idea of having something that was very accessible, that you could pick up on for free, that anyone could look at if they wanted to. The down thought is that I don’t know how many people keep up with my narrative. Hopefully, they can at least have some fun looking at it each week, and get some sense of the narrative, and look at the funny pictures.

SULLIVAN: Where was the strip first published?

BURNS: It started out in five or six papers in New York, the Bay area, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, maybe Denver and Phoenix. I can’t remember.

SULLIVAN: Did having to do an installment every week appeal to you, or was that a negative thing?

BURNS: Both. Up until very recently, I’ve liked the idea that no matter what, I’ve got to do x amount of installments every single month. That kind of deadline is helpful: it pushes you to produce regularly. But the down side is that if you want to take time off and reevaluate ideas and do something more experimental, that’s more difficult.

SULLIVAN: Is the format of the strip constricting?

BURNS: To a certain extent it is. But it’s also something I’ve chosen. I like having those restrictions sometimes. But there will be work in the future where I’ll at least make an attempt to step out and try other things, because I have been working in this grid for quite awhile.

SULLIVAN: The continuity in your strip is seamless; when you read it as a whole, it doesn’t back up and tell the story over again every week.

BURNS: Yeah, there’s no little recap. I don’t know if I’d be able to read it as a weekly strip. I conceived of it as full pages, so when I’m writing it, I’m writing full individual pages. But I’m aware of where it ends each week, too.

Each week in the continuing strip you’ve got two tiers of a strip, but I’m anticipating that they’ll be put into three-tier full pages. I’m writing on two levels: to have it function as a full page and as a weekly strip.

SULLIVAN: Is there a conflict there sometimes? How does that resolve itself?

BURNS: Surprisingly, there’s not really a conflict. Because I write it in a very rigid way. It’s almost like having sentences and paragraphs. Each tier kind of functions as a sentence, and a full page is like a paragraph. In the back of my mind I’m thinking about having them as full pages, but I don’t think it detracts from the weekly strip.

SULLIVAN: Is there a point of sale that you deliver to with an editor who says, “Can you make this clearer?” or anything like that?

BURNS: Nothing like that. It’s all just me. I even lick the stamps. I have a group of papers, and it’s not so large that I can’t take care of it myself. Once every four weeks I send out four strips. It’s in about 16 papers now; something like that. It hasn’t snowballed into this tremendous success, but when it all gets pieced together, it works out pretty well.

SULLIVAN: And the papers pay you individually?

BURNS: Yeah. If you look at it as a page rate, it’s a very good page rate. Some of the papers pay as little as 20 bucks, and others pay $75 an episode. I think they average about 40 bucks an episode.

SULLIVAN: Could you give the rough order of the stories that have run in the strip?

BURNS: First was “Teen Plague,” which ran in Raw [Vol. 2, #1], and then there was a Dog Boy story, and after that there was a very long story with a character called Bliss Blister. After that was “A Marriage Made in Hell,” which, in a different version, ran in Raw #6. That segued into the current Big Baby story. He goes to camp and meets a dead boy, a ghost boy.

SULLIVAN: How far in advance do you plot one of your stories?

SULLIVAN: How far in advance do you plot one of your stories?

BURNS: I’ll do an outline, so I know basically a beginning, middle and end, and I’ll have notes on that. I know what is going to happen, but I don’t know how it’s going to happen in some cases. So I’ll do a script for a month at a time, and I’ll keep revising notes and building on the story.

SULLIVAN: There is a dramatic tension in the Bliss Blister series; about two-thirds through the story, you switch to a different point of view and Blister sort of gets lost. Is that something you had planned to happen all along?

BURNS: Yeah, I was aware of that. I wanted to have a character that you sympathized with, and he suddenly turns into a nothing, a non-entity, a pawn in this larger story. As I was working, I decided I wanted to have a structure that was larger than just a personal voice.

SULLIVAN: Was that in part because of what was actually happening in the story — the fact that his plans were getting lost in all these other machinations?

BURNS: Yeah, exactly. He’s lost in everybody’s plans, so his voice gets lost, his brain gets lost. His hallucinations take over.

SULLIVAN: You said that story had been banned. How did that happen?

BURNS: It was a paper that had picked me up fairly recently in Jacksonville, FL. I got a call one afternoon, and this guy said, “Well, we’ve been getting calls, and we’re getting some pressure about the story.” I think the first two episodes of the Bliss Blister story had run, which is like the tip of the iceberg. They had some members of the religious community down there, saying, “Look, we can’t have this story. God does not have one eye.” Basically, the guy told me, “Look, I kind of respect what you’re doing, kind of … ” I could tell he was a little worried. “I mean, you don’t actually think that’s God, right? Right?” He was a little concerned about exactly what the story was, too. He was saying, “I don’t want to have a boycott. The religious community is going to drive us crazy by boycotting advertisers. What’s going to happen in the story?” And I said, “It only gets worse,” which is the case. So he skipped to the next story. He had started with the Dog Boy story and he said, “Yeah, we had some people call in. They didn’t like the idea of Dog Boy sniffing women’s butts. That’s OK, we can live with that, but when you start with the religious community, we can’t deal with that.” Sniffin’ butts is OK; God with one big eyeball is not OK.

SULLIVAN: And blisters shaped like Jesus on people’s chests.

SULLIVAN: And blisters shaped like Jesus on people’s chests.

BURNS: Exactly. Even after we had talked about the fact that he was going to drop it, he was asking, “Well, what happens, anyway?” “Uh, I can’t tell you. You dropped the story. I’m not going to tell you; it’s too difficult to explain.”

SULLIVAN: What kind of paper was this?

BURNS: All these papers are like free weeklies. They rely on advertising, primarily, for their bucks. And they usually have a couple of comic strips just for entertainment.

SULLIVAN: Were you mad about this? Did you discuss alternatives, like not running the strip in his paper anymore?

BURNS: To tell the truth, I don’t think that a strip I’m going to do is going to have much impact in that kind of paper … in that kind of community, anyway. The idea of my boycotting them … they could care less. If I said, “Oh, well, fuck you,” I know what his answer would be: “Thanks but no thanks.” He’s not going to stand up to the community. They’re a fairly small paper, and it’s just grief. They don’t need grief. They’ve got enough grief trying to put their paper out every week. It was a Baptist minister that had called up and was saying, “Get rid of that strip now.”

I think there was one other paper that got a letter to the editor about the Bliss Blister story. It wasn’t negative; it actually was kind of funny. Someone wrote in and said, “A very similar story to Bliss Blister appears in the Bible,” and described that particular story. So that was nice; he was saying, “this stuff exists in another realm, too.” I imagined there would be a stronger response to the story. I was surprised that there weren’t more letters to the editor, or people getting up in arms. In a way it was flattering that someone got upset enough to campaign against the editor and say, “We’re going to boycott your advertisers.”

SULLIVAN: I guess that’s a disadvantage of being in those free papers. You don’t have the rationale of “If you don’t like it, don’t buy it.”

BURNS: That was one of the things I really liked about being in these papers. Anyone could pick it up. You don’t have this comic community, this comic book store crowd. Not that I have any problem with that, it’s just that these papers get out to casual observers, people who just pick up something and see your work for the first time. People who would never go into a comic book store. I remember walking in New York City and seeing my comic strip rolling in the gutter. It’s not the kind of precious commodity that you’re faced with in a comics shop — not a collectible or a nice book. It’s a throwaway.

SULLIVAN: I was a bit amazed when I started seeing your strip in the L.A. Weekly, because of the sharp distinction between comic book and comic strip artists. In a sense, you ‘re breaking through that. Along with some other people.

BURNS: I tried to do that. When I think about weekly or daily strips, there are very few that I like. I mean, very, very few. I can’t think of any that are in a regular daily newspaper that I like. When I get a Sunday paper I don’t even look at the comics. They’re just too pathetic.

SULLIVAN: Why do you think that is?

BURNS: It hasn’t always been the case. I love old comic strips. I’m sure it has to do with the restrictions … there are so many restrictions. You’ve got to read a comic strip in three seconds. The exception would be something like Zippy. Bill Griffith is really getting back to what a daily strip should be. It’s amazing that an underground cartoonist is pulling something like that off. I have a lot of admiration for that. And there are a handful of very good cartoonists that appear in weekly newspapers. I like what Lynda Barry’s doing. I like Heather McAdams.

SULLIVAN: Do you get Michael Dougan’s strip out there?

BURNS: Yeah, he’s good. Sometimes he’s blasé, but when he’s good, he’s good.

SULLIVAN: How about Matt Groening? Do you read Life in Hell?

BURNS: I’ll look at it. You know, there’s nothing wrong with Life in Hell.

SULLIVAN: I think they’ll put that quote on the front of the next compilation.

BURNS: Ahhh. Put my foot in my mouth. No, it’s like a type of comic or humor that I’m not that attracted to. There are books that he’s put out and parts of his comic strip that I liked a lot. He did something that was like a grade-school diary. That was really good.

SULLIVAN: With your Dog Boy story, some of the panels are different between the newspaper version and the first version that appeared in Raw #7. Why did you change it?

BURNS: I wanted to expand on the story. At first, I always looked at Dog Boy as a one-liner. “OK, he’s got a dog’s heart, he acts like a dog and sniffs girls’ butts.” You could have an endless amount of dog jokes: burying a bone, chasing cars, sniffing, whatever. I was reluctant to expand on him as a character. I always liked him, and I found a way to flesh him out, even though he still remains fairly two-dimensional.

SULLIVAN: Have you seen Steve Lafler’s Dogboy?

SULLIVAN: Have you seen Steve Lafler’s Dogboy?

BURNS: I haven’t read it. I know what you’re talking about, though.

SULLIVAN: Have you guys ever had a conversation along the lines of, “There’s only room for one Dog Boy in this town?”

BURNS: No. I just know that mine was printed before his. And there are other Dog Boys that precede me. Justin Green had a Dog Boy. And maybe there’s another one. too.

THE HORROR, THE HORROR

SULLIVAN: A lot of your stories are related to the horror genre, but they’re not really horror stories. How do you make the distinction? How do you see your work as different from, say, Berni Wrightson’s?

BURNS: I don’t know. Maybe it’s a different intention, or not looking at the classic skeletal structure of what horror stories are supposed to be. I don’t want to do my version of an EC story, even though I’ve come close at times. I don’t have that admiration for trying to recreate some traditional story. Whatever horror imagery comes out in some way relates to my own personal vision of horror. I don’t know how to explain it.

SULLIVAN: You’ve done a lot of stories about transformations and invasions, like “Ill Bred,” “Contagious” and “Teen Plague.” What keeps drawing you back to this theme? What are you trying to express through that?

BURNS: I get asked this question all the time … I guess it’s this fascination I have with the separation of the mind and the body. And how the body can manifest a psychological state … The way Chester Gould would draw grotesque villains to show that they’re grotesque, I do stories like “Teen Plague,” where a devil rash starts coming out of a girl’s groin. There’s this very literal manifestation of this psychological state. Now, that’s clear, isn’t it? [Laughter.]

SULLIVAN: A lot of your work is very symbolic: The characters who are getting changed are often teenagers, they’re going through puberty, and they’re trying to make out, usually with disastrous results.

BURNS: Yeah, it’s like taking that kind of symbolism and twirling it in your face. For example, in “The Voice of Walking Flesh,” [Raw #4], this guy’s got a little thing that he attaches to his neck that’s literally like a little monkey on his back, and it grows as his addiction grows. It literally translates to “monkey on your back,” a physical manifestation of dependence and addiction. And in the same story, getting back to what I said before about severed heads, this guy’s wife has her head severed — I got the idea from a bad horror movie …

BURNS: The Brain That Wouldn’t Die [1963]. It’s very clear when you see it that it’s stolen right out of there. There’s one part that I lifted from the movie, where the husband revives his wife’s head, and he goes out shopping for a body. That just blew me away when I saw the movie. It’s perfect, he’s looking for some big sexed-up babe … even though it’s this dumb science fiction movie, a lot of guys do that. So that’s a story about how men can objectify the opposite sex.

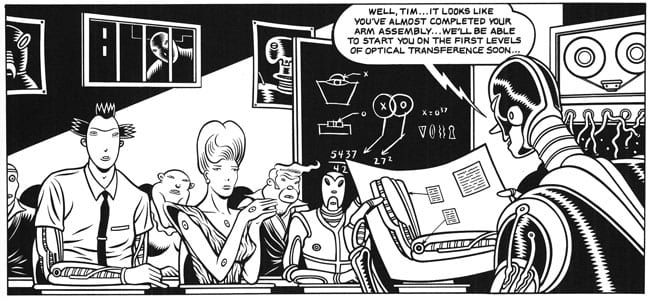

SULLIVAN: A lot of the characters in your stories seem to objectify themselves as well. In the El Borbah stories, people want to turn themselves into robots, or want to graft baby bodies onto their middle-aged heads.

BURNS: Yeah. Somebody doesn’t want to grow old, someone who has enough money to find out how to keep on being young forever. It’s just taking that to the extreme, where he’s actually turned into a baby again. But I don’t know if I can explain it all …

SULLIVAN: There does seem to be a strong theme of characters who are repelled by their own bodies, by aging, by all the sort of natural processes …

BURNS: Right.

SULLIVAN: … And by sex, of course.

BURNS: Yeah, it gets all lumped in there somehow.

SULLIVAN: It’s unclear whether you’re suggesting that these characters are wrong for being afraid of these natural processes as grotesque and frightening.

BURNS: I do that on purpose. I don’t like spelling something out. I like to present a series of images or ideas, and then piece them together, but not come up with an answer. Just to think about them.

SULLIVAN: The horror genre tries to strike a very direct emotional involvement with the reader — putting them in the position of somebody who is going to have something horrible done to them. You ‘re actually creating a greater distance between the reader and the story.

BURNS: Yeah, that’s fine. It’s just what I find effective. I know that I’m capable of throwing monkey blood on my audience. I’m capable of doing the kind of horror, like, here’s a severed jugular. But it’s never been my interest. I like the quiet, dry, psychological horror.

SULLIVAN: In a lot of your stories, men and women take on each other’s sexual attributes. There’s “III Bred,’’ and in “Teen Plague” the women have phallic tongues and inject men, who give birth to eyeballs that look like breasts. Are you working through something here?

BURNS: It’s not working through something so much. It’s being fascinated by those roles. Like, looking at an old movie and seeing how a woman is portrayed or how a man is portrayed, how plastic they are. There’s always something behind it; there’s a truth behind these roles. I’m examining all those things, and pushing them all together into extreme situations. “Marriage Made in Hell” is playing with all those stereotypes.

SULLIVAN: Are you being critical of those stereotypes?

BURNS: No; I’m just fascinated by them, I guess. In real life, I don’t want women to be bimbos, or men to be big lummoxes. Of course, it’s critical, in a certain sense, of roles and how women are portrayed through advertising, how men are supposed to be men, things like that.

SULLIVAN: At the same time you seem to be very critical about change.

BURNS: Yeah, no one gets off the hook.

SULLIVAN: In the El Borbah stories we’ve mentioned, you seem to be critical about ways in society in which people try to enact some radical change, either at a minute level, or at the level of trying to change society itself.

BURNS: OK. For example, in the El Borbah story where kids are turning themselves into robots, for me it’s fairly clear-cut that at a certain age all you want to do is conform. This is a situation, not of people wanting radical change, but wanting to conform, wanting to be with this group that has no emotions, that’s just zombie-like. That theme has been in a lot of my stories: the acceptance of some greater bland culture scheme, the need to accept what’s at the end of the spoon.

SULLIVAN: What about the story where men are exchanging their bodies for babies’ bodies? They’re not conforming, they’re trying some sort of radical self improvement.

SULLIVAN: What about the story where men are exchanging their bodies for babies’ bodies? They’re not conforming, they’re trying some sort of radical self improvement.

BURNS: No, it’s just greed. They’re able to do that because they’re rich businessmen. They’re taking scientific technology and using it for their own end. The improvement doesn’t strike me … all they want to do is continue with what they’ve got.

SULLIVAN: So it’s more a form of stasis rather than actually changing.

BURNS: In this particular case, yeah. It’s like buying youth. “Well … at least he has your hat.” The “Teen Plague” stories are more to do with sexual anxiety. Obviously, the direct AIDS metaphor is there — there have always been sexual diseases floating around, but now there’s a killer. I was just thinking about sex being this dangerous and frightening thing rather than what it’s supposed to be, which is just the opposite. I think when you’re an adolescent, that’s what’s affecting you the most, that kind of anxiety about who you are and what sex is. So that’s the reason it’s got that teen focus. I also like teenage movies, teens in general. They’re trying to find an identity, and being faced with the ultimate nightmare. The ultimate nightmare is that you’re at an assembly and someone says, “We’re checking everybody here for disease,” and you’re like, “Oh, shit. I’m going to infect my entire school.”

SULLIVAN: In the traditional stories you’re playing on, there’s a good pole and a bad pole. The good pole is being normal, not smoking, getting good grades. And the bad pole is being the evil teenager, who takes drugs or has sex or does whatever. In your stories, there are two bad poles. There’s the pole where you disintegrate into some skeletal creature, and there’s the pole where you’re this plastic, conforming, regular teenager.

BURNS: Right. That’s the anxiety I always had in that part of my life. I never wanted to fit in to that plastic conformity; I was always totally repelled. On the other hand, I felt like, “What’s wrong with me? I guess I should like to go to pep rallies. I should like to do all this other stuff that is just garbage.” You realize that you’re an alien in that kind of environment, and you question yourself because you don’t fit in. I’m fascinated by sexual roles, taking those roles and flipping them, examining what the consequences are.

SULLIVAN: They seem to be pretty horrific, usually.

SULLIVAN: They seem to be pretty horrific, usually.

BURNS: Yeah, I guess that’s so. I should lie down on my psychiatrist’s couch down here.

SULLIVAN: In “Ill Bred” there was less distance, less irony. There was a much greater horror, a more repulsive idea of what happens to this man in the story, but at the same time it was strangely attractive. It’s sort of a positive domination fantasy.

BURNS: I see what you’re saying. Somehow it gets resolved in the end, even though it is a horrific result. The problems are resolved in a very weird way.

Sometimes when I’m working through a story, I’m analyzing it and figuring out what effect things are going to have; occasionally I rely on a gut reaction to things. I don’t analyze why I’m coming back to this theme again and again. I mean, if I were Robert Crumb, I’d be coming back to big butts.

It’s difficult for me to analyze why I’m fascinated with these things. Do I want to be tied up and have eggs injected into me? Not really. I don’t think that’s the case at all. In one way [“Ill Bred” is] more personal because it’s told in a first-person narrative. So you’re a little bit closer to the character.

SULLIVAN: And he is more sympathetic as a character than some of your others. There’s always a distance between us and, say, Big Baby or Dog Boy.

BURNS: They don’t have a character, there’s no voice. They’re explaining the narrative or pushing the narrative forward. They don’t have this internal voice.

SULLIVAN: Aside from El Borbah, your protagonists always seem a little wimpy. When you were growing up, did you ever feel like you weren’t “one of the guys”?

BURNS: More in terms of what was in the media, not so much in my everyday life. I was a pretty average guy with friends who were pretty average.

SULLIVAN: But the media were presenting the “uber-males’’?

BURNS: Oh, yeah. I remember going to a James Bond movie and thinking, “Oh, God, I wish I could be more like that. He’s so cool. I mean, like my life is totally fucked.” It’s funny now, but I was dead serious. For one evening. The next day I was normal again.

SULLIVAN: Was there a point in your life when you became more directly critical, when you could say, “Yeah, I know what they were trying to push off on us … ?”

BURNS: I was always critical to a certain point. If you were reading Mad magazine, you were always aware of that edge: “Don’t take things too seriously.”

SULLIVAN: There are some similarities between your work and what David Cronenberg has done in his films. The critic Robin Wood has assaulted Cronenberg as a reactionary, saying he’s making horror films that portray sex and any kind of sexual deviation as absolutely negative, that this is homophobic and misogynist. What if somebody said that about your work?

BURNS: People already have. I’ve had people say, “You treat women like cardboard dolls.” I treat everybody like cardboard dolls. I can’t take it too seriously. I can only take it on a personal level; I can’t say, “I’m making a comment on sexuality.” I mean, I’m making comments about all sorts of stuff, but on this direct, personal gut level. I’m not trying to pass this big judgment that “Sex is evil.” I’m just having fun with those things, those ideas, those things that bump up against each other. Why am I fascinated with this? I’m not sure. I still don’t have the dead teenagers … the teenagers that come back from the dead … out of my system.

SULLIVAN: Do you think of alienation as a positive force? Do you think it propels people toward more creative endeavors?

BURNS: Oh, yeah, absolutely. It’s the nature of the work I do — there’s very little interaction. I sit in a studio and work for eight hours a day. I need to spend that amount of time alone, work all that stuff through. That’s just the nature of comics. I guess with the Marvel style, you’ve got a writer, inker, all that stuff. I don’t know if they all sit in the same room … I kind of envision everyone in an assembly line, where everything’s passed down to the next person.

SULLIVAN: Now they fax it to each other.

Do you consider yourself an ironic artist? Do you intentionally create irony or distance between the story and the reader, the story and the subject matter?

BURNS: I purposefully inject humor into stories so they don’t take themselves too seriously. Occasionally, I’ll find myself taking myself really seriously, and I’ll try to inject some humor into the material.

SULLIVAN: What’s wrong with getting serious?

BURNS: There’s nothing wrong with it, it’s just not the way I feel comfortable writing. It bothers me when I reach a certain point, it’s like going over an edge that doesn’t feel right. It’s not a fear of revealing myself, it’s just being too self-serious. I just need something to leaven that seriousness.

SULLIVAN: Do you think that affects the seriousness with which people perceive your work?

BURNS: I don’t know how people perceive my work. I’m sitting in a room and writing a story primarily for myself. I don’t know how people react to it.

SULLIVAN: You’ve taken as one of your artistic models these old comics which we now see as being very campy and stilted. The work is clearly not a reflection of something real. There’s a lot of that in your work. It’s almost like reading something you read naively as a child, and finding something grotesque in it as an adult, seeing what it was really about.

BURNS: Yeah, it’s also the other way around. There are things that I looked at when I was a kid that were actually very wild and amusing and entertaining, but I took them too seriously. I would build a whole story around a very simple image. It was meant to be fairly harmless, and would sit there and worry about it, trying to build this story.

I remember seeing anthologies of comics, and you’d see bits and pieces of all these different strips — a very small segment of a large body of work. Some fairly dull, pedestrian strip looked like it had endless possibilities by looking at one little tiny segment. What I was coming up with was a lot more interesting than the thing was in reality.

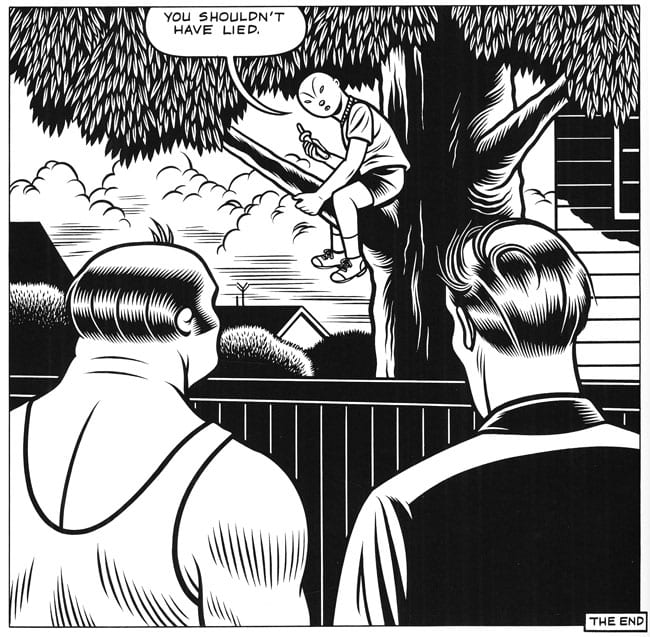

SULLIVAN: There’s a good example of that in Curse of the Molemen. We never learn what these creatures are that have this person apparently imprisoned in these tunnels underneath this suburban area. We just get this one image, and then bing, it’s all gone. The ending of that story is very odd. What were you trying to do there?

BURNS: It was like Big Baby had a certain larger understanding of the adult world. When you first see the men that are working on this pool, they’re playing around with him, going along with his fantasy about monsters under the ground. In the end, he’s accusing the adult world. He’s learning that it’s not what it seems.

SULLIVAN: It’s really chilling when Big Baby says, “You shouldn’t have lied.’’ The idea that this little unformed character has all the forbidden knowledge of the adult world …

BURNS: Yeah, in that one segment he’s starting to see the underbelly of adult reality, and he doesn’t like what he sees.

SULLIVAN: There’s also a sense that he can’t go back.

SULLIVAN: There’s also a sense that he can’t go back.

BURNS: Sure. I’m working on a Big Baby story right now that’s very similar, but pushing it even more. He sees too many things and slowly starts to close himself off to people around him.

SULLIVAN: That’s the scary thing about Big Baby — he seems incapable of normal psychological growth. So any sort of information he picks up gets added to some distortion.

BURNS: That’s how I use him as a character. It seems to be the theme that I keep going back to. He functions as a naive who learns about the adult world, the bad side.

Continued