Carlos Giménez has long been considered one of the great cartoonists, not just in Spain, but in the world. One of the first Spanish cartoonists to make autobiographical comics, he has made three very different series about his own life–Paracuellos, Barrio and Los Professionales. He has written and drawn many science fiction, historical and adventure series, adapted the work of Brian Aldiss, Jack London, Stanislaw Lem. He has made the historical series 36-39 and Spain United, Great and Free, and has been writing an adaptation of Arturo Perez-Reverte’s Captain Alastride series of historical adventures.

Carlos Giménez has long been considered one of the great cartoonists, not just in Spain, but in the world. One of the first Spanish cartoonists to make autobiographical comics, he has made three very different series about his own life–Paracuellos, Barrio and Los Professionales. He has written and drawn many science fiction, historical and adventure series, adapted the work of Brian Aldiss, Jack London, Stanislaw Lem. He has made the historical series 36-39 and Spain United, Great and Free, and has been writing an adaptation of Arturo Perez-Reverte’s Captain Alastride series of historical adventures.

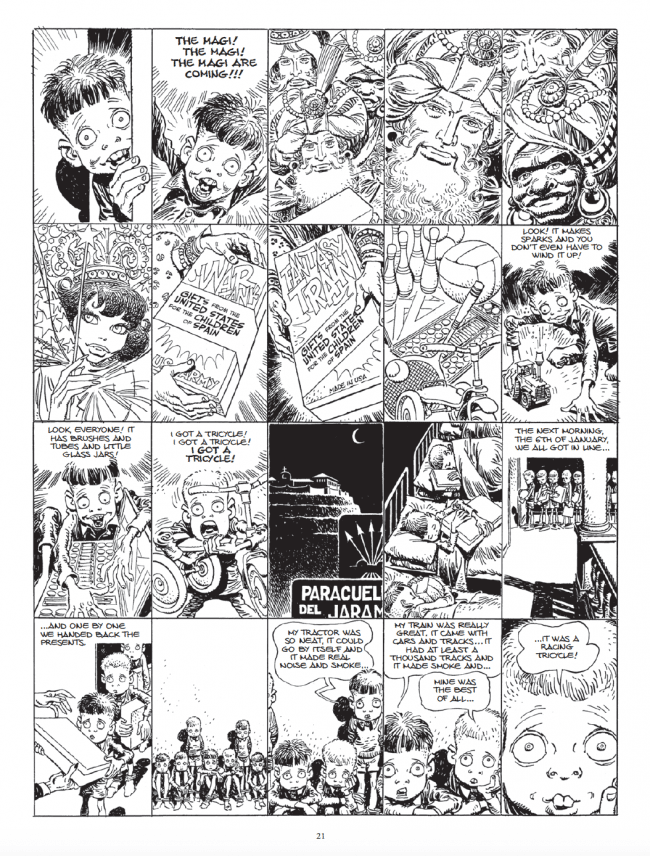

Perhaps his best known and most acclaimed work is Paracuellos, which Giménez began serializing in 1975. The comic began with Giménez telling stories of his own childhood growing up in a social aid home in Spain, and as he describes in our conversation, it became something bigger as the series continued. For those who don’t know, after the fascists led by General Franco, won the Spanish Civil War, they established a series of “homes” which were run by the state and the Catholic Church. Children who had either lost their parents–or were forcibly taken from their parents, because of their political views–were sent to these “homes” where they were brutally taught the lessons of the fascist state. Giménez does not shy away from the terror, hunger, and brutality that he and others endured and when the series was published, both he and the magazine received death threats for its criticism of the fascist state.

IDW’s EuroComics Imprint has just released Paracuellos: Children of the Defeated in Franco’s Fascist Spain, which collects the first two books of the series, translated by Sonya Jones. It includes a short forward by the late Will Eisner, essays by Spanish comics editor and historian Antonio Martin and editor Dean Mullaney, and afterwards by University of Kentucky Professor Carmen Moreno-Nuno and Giménez himself. The plan is to collect the entirety of Paracuellos and other books by Giminez in the future.

Thanks to translator Katie LaBarbera, who made this interview possible.

The first episode of Paracuellos was published in 1975 shortly after the death of General Franco. What was the response to the series?

The first episode of Paracuellos was published in 1975 shortly after the death of General Franco. What was the response to the series?

The first issue of Paracuellos–it wasn’t called that yet—surprised the editors of the magazine I was working for. At the time I was writing it for a humor magazine of the so-called “T&A” variety, but that strip had nothing to do with humor–much less T&A. The first episode caught them by surprise so they published it, but by the second or third they told me very politely, and with every reason, to get out. So I did. I tried some other magazines and was able to publish a few more issues. After forty years of fascist dictatorship and severe censorship the magazine editors wanted to publish funny stories about tits, but I was determined to publish stories about sad children in the “Homes” of postwar Spain.

Were you afraid to tell these stories initially and publish this?

No. I wasn’t afraid.

Your art style in Paracuellos is different from your earlier comics. Did you change your style because that's what you thought the story needed?

To draw the stories of the children of the Social Aid “Homes,” I chose the type of drawing that seemed right. Just as you wouldn’t draw a humor comic in the same style as you’d draw an adventure comic. In this case it wasn’t about drawing pretty children; what I had to draw was hunger, fear, and helplessness. At first, making the panels so small was for space reasons. With very small panels I could tell a larger part of the story. Later I kept this formula when I realized that the small panels left no room for backgrounds. And the only backgrounds I wanted were those that were essential to making the story easy to understand. Backgrounds embellish images, and I didn’t want pretty pictures, but rather sober and, if possible, claustrophobic panels.

In the first volume of Paracuellos you include dates, but in the second book, there are no dates. In addition to that, the later books shift from a first person perspective to a communal first person “we”. Was this an acknowledgement that it wasn’t just your story or about this one character?

When I started drawing these stories I wasn’t very clear on what I was going to be able to do, or how many pages I’d be able to publish. At the time I did the best that I could. Besides the title, on each story I put the name of the school where the incident occurred and the date that it occurred. I tried to make it look like a document.

I didn’t have any experience in writing scripts nor any aspiration that the stories would become a series. If some of the scripts were written in first person singular and others weren’t, it wasn’t premeditated. I tried to write sincerely, like someone who writes about things they’ve seen and tells them the best they can. They were the first scripts that I’d written.

By the second book I was treating it as a series, and I didn’t date the stories because the assumption was that they occurred in the same place and on the same dates. I even gave the characters concrete names and, since I had more paper, I abandoned the formula of two-page stories. More paper meant I could make the plots more nuanced, delving into the characters’ psychology and improving the dialogue. It was a relief. Paracuellos went from being a succession of disjointed anecdotes to becoming a story with characters that each had their own identity.

There were several years between the first and second–and then you wrote and drew four more books much later. Did you always plan to create more stories in the series, or were there other reasons you returned to Paracuellos?

Some time passed between the first and second books. The first book was published in France, in a humor magazine in fact, despite being “a story that instead of making you laugh makes you cry.” It was well received and won some awards, and that’s what motivated me to write the second book. I didn’t have any problems publishing the second volume of Paracuellos in Spain. All of the magazines that at one time rejected the stories now wanted to publish them. That’s life.

With the second book I finished what I wanted to say about the postwar “Homes” of Social Aid. Let’s say that by then I’d exorcised my demons. But without setting out to do it I began putting documents together. Old classmates from the “Homes” wrote me letters, sent me photographs, and told me about their experiences in interviews, which I recorded on piles of cassette tapes, until I had so much material that it seemed a waste not to use it. And that’s how I went back to the series.

Besides Paracuellos you’ve made a number of autobiographical works like Barrio and Los Professionales. Were there many other autobiographical comics in Spain when you first started?

No. Nobody that I knew of used their own life stories and personal experiences to write and draw their comics. Afterwards many people did. I don’t imagine that it’s any special achievement. Somebody has to be the first. What’s important is telling a good story and telling it well. It doesn’t matter if the story is autobiographical or not.

You've created all different kinds of comics—including adapting stories by Jack London, Brian Aldiss, and Stanislaw Lem. Do you take a different approach to adventure or science fiction than you do autobiography and non-fiction?

Yes. The stories that interest me as a writer are often tedious to draw, as they’re repetitious and monotonous, whereas the adventure and science fiction ones are pretty and fun and I thoroughly enjoy drawing them. I’d say that the writer in me is interested in real life and society, whereas from time to time the artist in me enjoys drawing figures in motion and imaginative scenes. In any event, whether I’m drawing something realistic or fantastic, I always try to include a social commentary or political opinion in the plot. Otherwise I’m not happy with it.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the start of the Spanish Civil War. Has the mood changed in Spain? Have people been trying to look at what happened during the Civil War and the Franco regime, or has this historical amnesia continued?

Unfortunately, despite the amount of time that’s passed since the war ended in Spain, there are still Fascists. I’d even say that lately they’re multiplying at an alarming rate. And not just in Spain but all over the world. Morality’s on the decline, racism is on the rise, there’s hatred towards immigrants and refugees. We forget that everyone, ourselves or our grandparents, at one time were immigrants or refugees.

This question of historical memory remains so important today–I know people all over, from Lebanon to Argentina to Ireland, who wrestle with this. What do you think that artists can do? How can art help?

I was also a pioneer in the question of historical memory. Paracuellos is a good example. A friend of mine told me, “This historical memory, Carlos, you invented it, what happened is that you didn’t know it was called that.” I think it’s good to not forget. I believe that it’s true about how people who forget their history are condemned to repeat their mistakes and suffer from them over and over again.

In regards to the role of the artist in society, who am I to tell anyone what they should do? In the first place I don’t consider myself an artist, or hardly even an intellectual. I’m a teller of tales, a storyteller, like those who traveled through villages with their hand-painted signs, telling the stories they knew and relating in one place the stories they’d heard in another. But I’m a man of my time and social class, who tries not to forget history, a man who can discern what’s just from what’s not, and who thinks that it’s cowardice to remain silent when we have this megaphone in our hands (courtesy of our profession), and when we see so much pain, inequality and injustice all around us.

Do you have a favorite project of yours? Is there something you hope will be translated soon?

I’d like my books to be published in the United States. American publishers have never appreciated my work because, they say, it’s a far cry from the tastes of American readers. I think that there could be a group of readers that my stories would be of interest to. I believe there are readers for all tastes. For me, it would be a very special achievement to see my stories published in the country where comics were born.

What are you working on now? What's your next project?

Right now I’m working on a story titled The Discriminator that talks about (in a funny but caustic tone) the mass media and the manipulation that they, publicists, panelists, and media magnates exert on the defenseless citizen that suffers, supports and pays them. There’s also a superhero in the story, and a cartoonist. My most immediate project is to see it finished and, if possible, published.