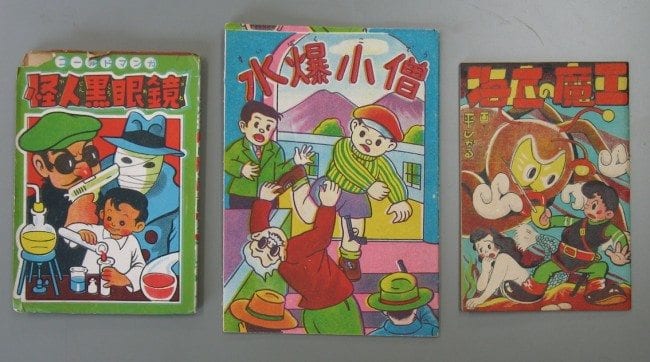

It is not often that I find something and immediately want to share it with the readers of The Comics Journal. But it is also not often that I find something like I did one recent afternoon in Tokyo: a small stash of three akahon manga from a nameless publisher that I will call, affectionately, the Shitgrin Mask.

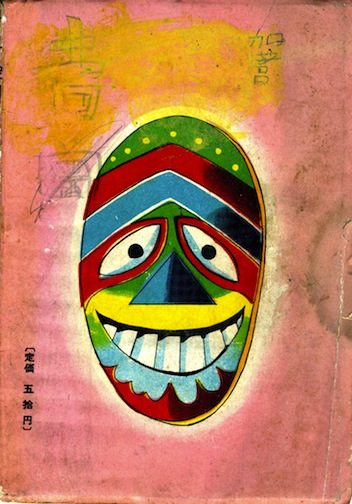

The reason I have had to manufacture a name is because the books in question provide no commercial data other than their price (5 yen). Such information is typically sparse on akahon – forget finding a date – but at least there is usually a publisher name (even if phony) and sometimes even an address (if you’re lucky, but even then you are probably being lied to). Admittedly, no Japanese would have used such a name. Benign things like Osaka Manga Company, The Art Company, Araki Publishing, or Enomoto Books were typical. The name I have not pulled out of thin air, however. The back cover shows a Polynesian-looking mask with dopey eyes and a big shiteating grin. Some boy named Kago Kazuhiko has penciled his name in hiragana on two of the volumes. On the third, it looks like he has botched his name in kanji. As you will soon learn, little Kazuhiko had very bad taste, or at least his parents did when they bought these comics for him in the early 1950s.

The reason I have had to manufacture a name is because the books in question provide no commercial data other than their price (5 yen). Such information is typically sparse on akahon – forget finding a date – but at least there is usually a publisher name (even if phony) and sometimes even an address (if you’re lucky, but even then you are probably being lied to). Admittedly, no Japanese would have used such a name. Benign things like Osaka Manga Company, The Art Company, Araki Publishing, or Enomoto Books were typical. The name I have not pulled out of thin air, however. The back cover shows a Polynesian-looking mask with dopey eyes and a big shiteating grin. Some boy named Kago Kazuhiko has penciled his name in hiragana on two of the volumes. On the third, it looks like he has botched his name in kanji. As you will soon learn, little Kazuhiko had very bad taste, or at least his parents did when they bought these comics for him in the early 1950s.

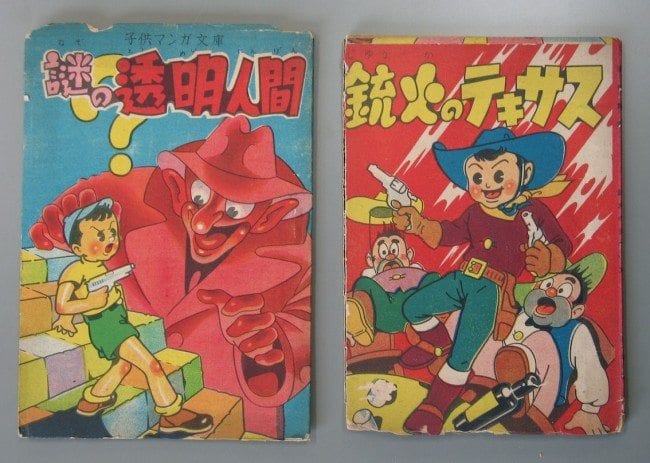

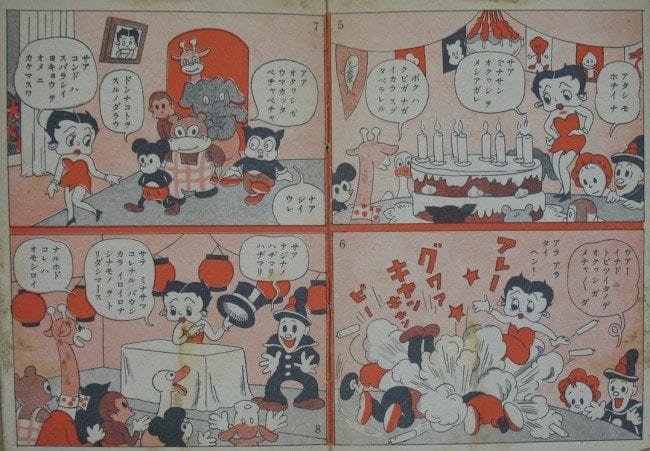

What is an akahon? The name literally translates “red book,” an Edo-period name for children’s books distinguished by their red covers, revived in the Meiji period for various sorts of adventure and comic fiction aimed at youth, and then associated most strongly with certain types of manga after the 1930s. The hardbound, sometimes slip-cased editions of Norakuro and Tank Tankurō issued by big publishing houses like Kōdansha were not akahon. The typical akahon was a stapled booklet with a card-stock cover, sixteen to thirty-six pages in length, and with lots of reds and oranges printed over black or purple line art. The art is usually larger. The selling price much cheaper. Generally the jokes also cheaper and more slapstick oriented, but things like Tank Tankurō indicate that, between pre-1945 akahon and their more expensive peers, differences in drawing and sense of humor can be slight. One last thing is typical of akahon: laxness regarding copyright. Cover art was recycled without permission. Characters were freely swiped from popular manga and animation. And foreign stars were just as subject to cameo.

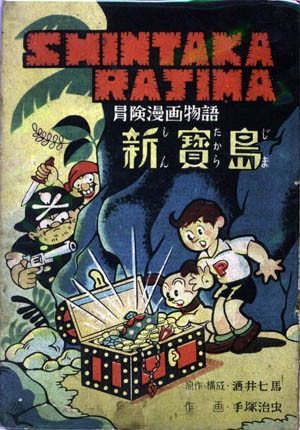

In the postwar period, the center of akahon publishing shifted, for a short time, from Tokyo to Osaka. Postwar akahon coincides more or less with the Occupation, peaking in 1948 or 1949. While varied, they are all quite different from their prewar namesakes. Physically and stylistically, they are clearly products of an age of want. They are flimsier, sometimes due to lack of high-grade paper and printing facilities after the war, sometimes from simple cost-cutting. The anything-goes energy of the age fueled many artistic innovations, some lost to history, others becoming the foundation stones of story-telling in postwar manga. That same energy also supported a black market mentality of only-wrong-if-you-get-caught, especially when it came to pirate editions and degraded copies of the field’s most popular titles.

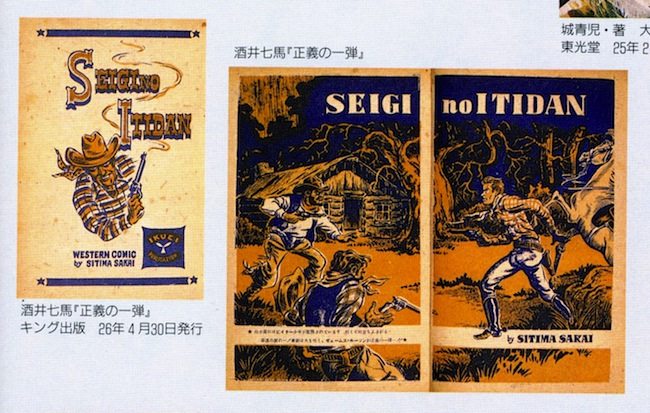

While it is not always possible to separate one from the other, generally speaking akahon were made and sold in two ways. There were a number of legitimate publishers, some even with prewar roots. Their products were mainly sold through bookstalls and train station vendors, and are generally printed better, bound better, and drawn by artists invested in their work. Tezuka Osamu, Sakai Shichima, Tanaka Masao, and Kuroda Masami belong in this camp, as do their publishers Ikuei Shuppan, Toyota Bunko, and Mishima Shobō. Content ran the gamut, from Westerns and samurai swashbucklers to schoolyard slapstick and boy detective comedies. Drawing styles are just as varied. There are some done in a Disney-derived style, most famously Tezuka’s work, which sold in the tens of thousands. Some, particularly emonogatari, in a simplified naturalism with roots in prewar illustration. Sakai, best-known for writing and laying out the legendary Tezuka-drawn New Treasure Island, drew in a mixture of both, with the added influence of American comics received from Osaka area G.I.’s.

It is on the basis of those parties’ hard work and talent that akahon manga can justifiably be described as the fountainhead of postwar manga. Not all akahon artists or publishers deserve that honor. It is useful to keep in mind that these were boom times for publishing. During the early Occupation period, it was said that anything printed sold, and it was such that in the late 40s, when shortages of paper led to government controls, a fairly large-scale and big-money black market trade developed to keep presses rolling. The hunger for books extended also to manga. Seeing the success of Tezuka and his colleagues, people with no prior experience in making or publishing comics raced to get a slice of the pie. Candy and toy sellers, main vendors for akahon, began themselves to publish. Printers and paper brokers took advantage of their position and likewise started to put out their own books. While there are some gems, most such akahon were not meant for posterity, physically or artistically. These akahon are recognizable by their size, typically B6, and are printed with heavy cardstock covers and rough newsprint pages. They rarely exceed thirty-six pages.

There were smaller varieties known as “pocket” akahon and even “baby book” akahon. This might make them sound like Cracker Jack comics, but they're larger and the art is often as good as what one finds in top Tokyo magazines. Such akahon seem to have been sold mainly through candy and toyshops, and some were intended as prizes at festival-day game stalls. It is for this reason that they are often called “omocha manga,” “toy comics.”

Akahon meant no one thing, as you can see just from an array of formats. The name is hardly more than a catch-all, excluding really only things printed magazine-sized or as hard-bound books. “Cheap children’s books, mainly comics, printed during the Occupation” is probably as restrictive a definition one should give. It’s not even wise to add “mainly in Osaka.” Akahon might have been Osaka-centric just after the war. But according to an article in the Asahi Weekly, by 1949 akahon publishers in Tokyo outnumbered those in Osaka three to one, at least when it came to those with more than a couple books to their name. In the postwar period, even “red” was not all that dominant.

The high-grade exceptions notwithstanding, akahon have long had a reputation for begin the junk food of manga history. Even in their day, Tokyo professionals were casting aspersions. The above-mentioned Asahi Weekly article canvassed top Tokyo cartoonists for their thoughts on the akahon boom. Yokoyama Ryūichi says, “Akahon manga are all made from copying. They are copies of foreign comics, and Japanese comics in popular magazines.” He continues, “The people who draw akahon manga are no more talented than elementary school children. Anyone could draw them.” Kondō Hidezō upped the ante: “The base of vulgar children’s comics is Osaka. People from that city are generally like that. The most important thing to them is money. They have no shame. That shamelessness created akahon manga. They look at this stuff and are delighted.” And then referring to the seventh-century Buddhist temple in Nara that was partially torched three months earlier in January when a workman forgot to turn off his electric heated zabuton at the end of a day restoring the temple’s murals, “Akahon sell, Hōryūji burns. Thus is Japanese culture today.” Obviously much prejudice was behind the reception of akahon. And some ignorance: after all, akahon manga had first thrived in Tokyo in the 30s, and the center of publishing had shifted back to the capital by the time Kondō was talking shit. But still these views were not entirely without foundation. There was limited respect for copyright, as you will see below. Pseudo-Tezukas proliferated madly. Not only talentless adults, but even children seem to have been involved in production. From their price and printing, many are clearly designed to have been thrown-away. Some were trash to begin with.

It is the bottom of that barrel that this essay is concerned with. Please keep in mind that what you are about to see is not even representative of bad akahon, let alone the field in general. The comics of the Shitgrin Mask are simply the worst. They are misleading examples of akahon in the sense that they exaggerate all the negative stereotypes. Also keep in mind that these comics were not made in the spirit of art brut or some more recent edition of ironic deskilling, even if such underwrites appreciation of them in the present. These manga are not, in that sense, “art” – at least that is my understanding. I think it more useful to see them as expressions of a “seller’s market,” certainly the purest such that I know of in the history of manga. These comics may seem to you hardly worth the paper on which they were printed. But know that they circulated in the many thousands. A smaller run would not have been worth the investment. These comics only existed to sell, and since they no doubt did, their existence is probably also a sign that when they were made – judging from their printing and content, and I would guess just after 1950 – at that moment the akahon market was quavering from over-inflation. The manga bubble never did burst, as you know from subsequent Japanese cultural history. But if there is a visual expression to the flatulent sound of air escaping from the akahon market, this is it. By 1950, most akahon talent had moved to the new flush of children’s magazines, hardbound books for rental libraries or retail, and kamishibai. Akahon was left a litter pit, and the scavengers swarmed.

(Continued)