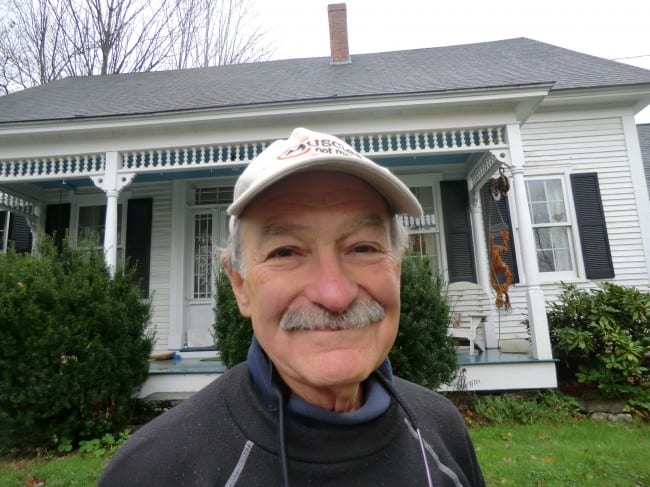

Shortly after I arrive at Edward Koren's home in the town of Brookfield, Vermont (pop. 1310), the squawk box he keeps close by comes to life and he gets called to a fire. A car is burning on the local interstate, and Koren is a volunteer fireman of some three decades. He dons his turnout gear – heavy heat-resistant jacket, pants, and helmet – and we hop into his gray Saab. Fortunately, the burning SUV is only smoking. Koren and the rest of the rather younger crew position safety cones, force open the car's hood, and spray it down. Mission accomplished.

It's just another day in the life of the transplanted New Yorker. Since selling his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1962, Koren has mined a deep, rich vein of humor centering mostly on the values and vanities of Manhattan's Upper West Side. He bought his Brookfield house in 1976 and "oozed" up there permanently in 1987. Since then, his cartoons have just as often zeroed in on the permanent and weekend inhabitants of what Koren calls "the Vermont profonde.

It's just another day in the life of the transplanted New Yorker. Since selling his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1962, Koren has mined a deep, rich vein of humor centering mostly on the values and vanities of Manhattan's Upper West Side. He bought his Brookfield house in 1976 and "oozed" up there permanently in 1987. Since then, his cartoons have just as often zeroed in on the permanent and weekend inhabitants of what Koren calls "the Vermont profonde.

The young trick-or-treat-er wearing a scowling mask, who replies "Can't you tell? I'm a depressed and angry white working-class male" as he waits for his candy on a pumpkin-decorated porch sure didn't grow up in the West Village. And Koren's most popular New Yorker cover in recent years (July 2, 2012) depicts an oblivious fellow riding a lawnmower and grooming an impeccably square patch of lawn as sad beasts peer at him balefully from the surrounding forest. Koren is a keen observer of our increasingly skewed relationship to nature, and "the issue of the giant lawn" and "this absurd desire to hurry home and organize nature" troubles him, frankly. And judging by the unusually large response he got to his work, he's not alone in his concern.

The New Yorker's finest social critic of his generation and milieu toils in the artistic tradition of both Honoré Daumier and Saul Steinberg. In addition to being a prolific New Yorker cartoonist and cover artist, Koren has also produced a substantial amount of "serious" art since graduating from Columbia University in 1957. Writer Calvin Trillin called it Koren's "Fine Art of Uptown Stuff," but, as Koren explained in the Artist's Note included in the catalog for his 2010 show "The Capricious Line," "I always thought that my comic work was fundamentally serious, and what might be called 'serious work' had its basis in my generally comic disposition."

GEHR: Do any particular artistic triumphs pop into your head when you consider your half-century career at The New Yorker?

GEHR: Do any particular artistic triumphs pop into your head when you consider your half-century career at The New Yorker?

KOREN: Any time something appears there, it feels like a triumph of sorts. It never becomes routine. I mean "triumph" in the sense that there’s some response. Because oftentimes, most of the time, there’s none. Zero.

GEHR: Do you ever feel like a Kremlinologist pondering the magazine's editorial decisions?

KOREN: I think of it as fishing rather than Kremlinology. You bait the hook with your wonderful drawing and throw it in, but you have no idea what’s going to happen to it. It might get nibbled away and you come up with an empty hook; but most of the time you just come back with the worm, the drawing, still on it. You have no idea what’s going on down there. It was never different. It’s a crapshoot. You have to accept it as part of the process, as best you can, because it’s not so easy.

GEHR: What was your first introduction with The New Yorker?

KOREN: I guess my work was introduced in a roundabout way to [former art editor] Jim Geraghty through a Connecticut neighbor of his whose son went to Columbia, where I also went. It might even have been one more person removed, but someone showed it to Geraghty. I was very actively involved in Columbia's humor magazine, The Jester. I started when I was a freshman and ended up being the editor as a junior or senior. A huge chunk of my life was spent either writing or drawing for the magazine.

GEHR: How many cartoons and covers have you published in The New Yorker?

KOREN: About a thousand fifty cartoons. Something in there, close to that. It’s inching up. And I think close to thirty covers. It’s been a while since I’ve kept track.

GEHR: Was the magazine around the house when you were growing up?

KOREN: I was much more devoted to the comics pages of the New York World-Telegram and Sun, which my father brought home every night from New York. I would make a beeline for it. Also our local paper, The Mount Vernon Daily Voice which had a cartoon page. I loved Fontaine Fox's "Toonerville Folks" and V. T. Hamlin's "Alley Oop."

GEHR: There were some pretty hairy people in "Alley Oop." Any connection to your own characters.

KOREN: Not specifically, but I remember the look, the characters, and the set-ups. And I remember the black-and-white contrast in those drawings. But thinking about it right now, somehow those fuzzy, hairy creatures got to me, in a subliminal way. I read comic books a lot, too. Captain Marvel was a favorite, and Superman and Batman – the superheroes. And Dick Tracy.

GEHR: What was working with Jim Geraghty like for you?

KOREN: He had a whole different editing mode than [his successor,] Lee [Lorenz] did. Geraghty wasn’t an artist, as Lee pointed out [in The Art of the New Yorker 1925-1993], which was both a problem and not. Because if it was a problem, he wouldn’t have gotten that array of extraordinary drawing, draftsmanship, and thinking into the magazine. He probably had the genius to put together the captions, gags, drawings, and artists. I didn’t know that all artists didn't think up their own jokes. I thought it was all from the fount of the brain and hand. I was horrified when I learned the truth – "What kind of artist is this?" – and I thought less of them, in truth. But now, of course, I’ve changed my mind quite a lot. Because I think the genius is still in the hand, the vision, and the whole world that’s characterized by one specific, particular artist such as George Price, who never thought up anything. Price only had one idea of his own: Santa Claus on the subway. That was his. Every other cartoon was not.

GEHR: How do you see The New Yorker fitting into the larger satirical tradition of visual art?

KOREN: I think it’s very much part of that frozen moment of time where a story’s told. That’s the tradition, which goes back to the eighteenth century with Hogarth, Rowlandson, and Gillray. There are more telling parallels, maybe, with the French nineteenth-century caricaturists like Daumier, Grandville, Gavarni, Sem, and Gustav Doré. They’re all storytellers. Some of it’s funny and some of it’s not so funny. Some of it’s political and a lot of it is social. Some use animals, some don't. We only understand a lot of Daumier's drawings theoretically, because the situations are so specific to the time. What’s most attractive to me is his social world: the lawyers and doctors and how he saw them and can make a story out of them with those drawings. He never really wrote anything, either. He just did the drawings, and the captions were written afterward by his editor, [Charles] Philipon, or other staff members of La Caricature and, later, Le Charivari.

GEHR: Daumier was jailed because of his caricature of Emperor Louis-Philippe. But the subjects of New Yorker cartoons probably don't even recognize themselves.

KOREN: The more critical, the more they love it. It seems that the East Side group William Hamilton satirizes so well loves seeing itself. It’s almost like publicity for them. There’s no such thing as bad publicity, and there’s no such thing as a bad satire. [Laughter.] You'd think they’d be offended.

It’s funny how some cartoonists have their venue and cast of characters, and Charles Saxon certainly had his, too. He had a terrifically sharp eye for the self-satisfied, well-off, upper-middle-class Fairfield County country club-ers. The commuters. That whole world he lived amongst. They were more hapless and less interesting, in a way, except when he dealt with them. And sometimes it was almost too gentle. You almost wanted to say, "Go at ‘em, Saxon!" I sometimes feel like I should be a little bit more of a sledgehammer than a feather. That’s me, though, and I can’t change it.

GEHR: Do you see anyone else like Hamilton or Saxon coming up in The New Yorker?

KOREN: Yeah, the one working today who has more of an edge than anybody is this interesting guy named William Haefeli. He’s in The New Yorker a fair amount, and he’s got these very quirky, stylized, descriptive drawings. He’s a very interesting artist, maybe even the most interesting one to come along in a long time. He can be so graphically and satirically economical and on the point. I like that. The other ones: sometimes yes, sometimes no.

GEHR: The New Yorker used to really depict the city through its cartoons. It taught people how to look at New York in a very specific way. It constructed a New York just as much as movies did.

KOREN: Well, it did that when New York figured more in the drawings, which it doesn’t now. There’s this great Ralph Barton drawing from the thirties, with garbage men throwing garbage cans around in a giant courtyard. It was a beautiful drawing. And that was New York. That was exactly what New York would be like. He had a way of characterizing the almost primal and demonic noise made by the garbagemen. It was fascinating. He got a lot the city's abrasiveness as well. There were so many drawing like that. Alan Dunn was a consummate draftsman of the city. Charles Addams got a lot of the city with that Halloween cover [October 31, 1983], with the wonderful contrast and great point of view looking down on the taxi and the doorman. There was a lot of that. Now, I’m not so sure.

GEHR: Are you conscious of doing social journalism as a cartoonist?

KOREN: In a way I'm always conscious of that, because that’s what I’m really interested in. I hearken back to those nineteenth-century French caricaturists and, in particular, my mentor Monsieur Daumier. I just love his feel for subjects, his sense of the moment of their lives, and how he reads character in relation to their social situations, what they’re doing, and where they are on the social ladder. I draw a lot of inspiration from that. I’m not a sort of person who mixes that easily. I always sit on the sidelines looking, taking it in. I've learned a lot from artists like John Sloan, Thomas Hart Benton, Reginald Marsh, and the Ashcan artists, who were really out there looking at New York in social terms. That fascinated me.

GEHR: When and where were you born in New York?

KOREN: December 13, 1935, on a Friday, in Woman’s Hospital, which is now a giant Con Ed substation on 110th and Amsterdam. I was born in a substation, so electricity was transferred to my hands like a comic-book superhero, and it’s been there ever since. [Laughter.]

GEHR: Happy to finally learn your secret origin. [Laughter.] Did your parents live in the city at the time?

KOREN: They lived in Bayonne, New Jersey, and moved to Yonkers after that. My mother was a schoolteacher and my father was initially an electrical engineer.

GEHR: Nearly every New Yorker cartoonist I've spoken to has had at least one parent who was a schoolteacher.

KOREN: I wonder if there’s some connection to that and what we do, which is, in some way, pedagogical. There's a lot of turf in-between, but you still feel like you’re instructing, in some round-about way and, one hopes, without the seriousness and reformist tendencies.

GEHR: Where was your mother from?

KOREN: Her name was Elizabeth Sorkin and she was born in Belorussia. She was an elementary school teacher, and she ended up visiting kids who were in the hospitals, or who were sick at home. It was called home and hospital teaching.

GEHR: How about your father?

KOREN: He was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1898. She was born in 1900. His name was Harry. I think there was some other last name, originally, but we think it was changed at Ellis Island. We’re not sure, because there were a whole lot of Poles named Koren who had worked as shipbuilders in Holland. It’s hard to unravel whether it’s Korenvitz or something else. At any rate, he came to this country when he was eleven or twelve. My mother was about the same age, or a little younger. Their families moved to Staten Island and then to Bayonne. They met as students. She went to a normal school somewhere in New Jersey and he went to Cooper Union. He worked his way through school. They both worked like one can hardly imagine now. Well, you can imagine it in terms of some of the other ethnic groups coming into New York. But they were the ones who worked sixteen-hour days, doing all kinds of things, just to get themselves going. He worked as a brick layer, taught brick laying at a trade school, and worked for an architect part time, all while going to school. He went to Cooper Union to study electrical engineering, got a degree in 1920 or '21, and couldn’t get a job. He was a Jew and they weren’t hiring Jews. How did they know? Because they always asked for the recommendation of your pastor or priest. So he got discouraged and just couldn’t find a job, though I’m sure he was tremendously competent judging from his subsequent profession, dentistry. He and my mother decided that the only way they could avoid this restrictive world was to become independent. So he went back to college, got the requisite liberal arts degree, and then went to Columbia Dental School. He got his DDS and practiced in New York City for close to thirty years.

GEHR: You must have spent a lot of time in his office.

KOREN: I did. It was a favorite place of mine. I would help him in the lab.

GEHR: Did he want you to become a dentist?

KOREN: Or even a doctor. [Laughs] I was pre-med as a Columbia freshman, joined the pre-medical society, and took physics, chemistry, and math. I was terrible at all of it. Horrible! During the first couple of weeks, I went to a film of a thyroid operation that the pre-medical society was showing, and I literally got sick. The next day I was no longer pre-med. [Laughter.] At that time you could really sample the great smorgasbord that Columbia had. And I think Columbia, even more than Horace Mann, where I went to high school, was crucial to my coming along. Now that I look back on it, I'm able to understand the value of education.

GEHR: When did you first start identifying as an artist?

KOREN: I was a great rival of one kid at Horace Mann who was a very fine painter. Michael Mazur was his name, and we became much more friendly after we graduated. We were on the same footing, but at that time he was much more advanced than I was. He was part of the New York art world. He was a very good draftsman, but in a classical way. And that’s when I first started drawing cartoons. They were my key to being accepted. I was the solitary, sort of marginal, shy kid from the ‘burbs, and not anywhere near as sophisticated as the kids from Manhattan. They were richer and more urbane. I was a bumpkin. [Laughter.]

GEHR: Did you work on the school paper and literary magazine at Horace Mann?

KOREN: I worked on the yearbook and literary magazine. I joined editorial boards and I contributed to all of the programs, particularly for the football games. All of that garnered a certain acceptance. You know, the funny guy, the jester. "Isn’t he cute! Isn’t he wonderful!" So for somebody without any confidence at all, about anything, it was pretty critical. And the same thing was true at Columbia.

GEHR: Working for The Jester .

KOREN: One of the great moments for me was when I did something somewhat political. I think it was my senior year. The administration had proposed something called "Citizenship Program," which was basically voluntary service to the community. Today I would say, "Gee, that’s a damn good idea." But back then, all of us being very uptight "scholars," and taking our student work seriously, I was against it, as were a lot of my friends. We thought it would be forced labor of sorts. So I lampooned it. I devoted an issue of Jester to it, and we just skewered it. Lionel Trilling congratulated me for a wonderful issue and said how appreciative he was.

GEHR: What did you do after graduating from Columbia in 1957?

KOREN: I thought I'd be an architect, but I couldn’t do the math. I had applied to Yale's graphic-design program because I figured, OK, I’ll be a graphic designer. I also was thinking that at some point I’d be a city planner, because I was interested in the urbanscape, the built environment. City planning and architecture were similar, but one didn’t require math. I was accepted into Yale for an MFA in graphic design, but I put it off for a year. I worked at a city-planning firm for about six months. It was an awful job. It put me right off city planning, at least as practiced then. It was all statistics, and it all had to do with razing perfectly good neighborhoods for Title I housing. So I said "screw this" and went to see Dustin Rice, an art-history professor of mine at Columbia, and said, "I don’t know what to do. I don’t want to go to graduate school yet." He said, "Why don’t you go work with my friend Bill [Stanley William] Hayter in Paris? You’re interested in graphic design, printmaking, and all that. I said, "Who’s he?" It turned out he was the twentieth century's premiere resuscitater of etching and engraving. Hayter said, "Sure, send him over!" So I quit the job and a girlfriend broke up with me, coincidentally, so it was a perfect time to go. I took the SS Flandre, a French Line boat, to England. My college roommate had gotten a wonderful fellowship to go to Cambridge for two years, so I hung out with him and his buddies and went to Paris from there. I showed up at Hayter’s studio and spent a year and half there.

GEHR: Was it all very Henry Miller-ish for you?

KOREN: I wish it was. [Laughter.] Again, I was very – I’m isolated. I’m a very solitary guy. I mean, I had a few friends here and there, but it was a lonely life. But I think I became a mensch when I was there. I finally grew up just by having to deal with a lot of things I'd never had to deal with, in an independent way.

GEHR: What else did you learn there?

KOREN: I learned how to etch. But a lot of it was just learning Paris and going to museums a lot. I really focused on that. I’d sketch and draw and walk and look.

GEHR: Were you in the military?

KOREN: In ’59, I came back to join the Army. I joined the Army Reserves because my number had come up and they wanted to draft me. The alternative was that we could either join the National Guard or the Reserve voluntarily, and have six months of active duty and six years of inactive duty. It meant you went to training either every week or every weekend, and spent two weeks every summer training. So that’s what I opted to do. It was a lot easier than two full years. At Fort Dix I just sat around, drew, and did what people did in the army: goldbrick a lot. Because there’s nothing to do. I wrote press releases for local papers.

GEHR: Did you work for Bottling Industry magazine after basic training?

KOREN: I’m stunned. Richard. You really dredge this stuff up. Yeah, I did.

All I did was rewrite press releases: "Pepsi to debut bottling plant in Winona, Wisconsin" and "So-and-so named VP of Carbonization." [Laughs.] It was dopey, but it was a job. I was living with my parents and driving into the city every morning. It was about a year before I got married in April ’61. In those days you could drive into the city, park on 60th Street and Madison Avenue, and leave the car all day. [Laughter.] I worked there for about three months. Then I went to Associated American Artists and put together their catalog. It was a gallery on 57th Street which specialized in prints, and so my expertise came to the fore. Then I got a job at the Abelard-Schuman publishing company. And then I was offered a job at Columbia University Press as the assistant advertising manager, which I took because it paid more and was more interesting than Abelard-Schuman. So I did a lot of direct mail print advertising for the Press for more than a year. My ex-wife was working for Commentary magazine and then got a job at American Heritage. And then I decided that I wanted to be a cartoonist; I wanted to be an artist. I didn’t want to go nine-to-five; it was not fulfilling. I'd joined a studio on 17th Street, run by {Robert] Blackburn, called the Printmaking Workshop. I did a lot of printing down there. And then I would draw cartoons and start to make the rounds. After trying in a very desultory way for a long time, submitting and then not submitting for a while, The New Yorker finally took a cartoon in 1962.

GEHR: Who else were you selling to?

KOREN: Dude, Gent, True, Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, Look, Male Testosterone, whatever they were called. [Laughter.]

GEHR: You also returned to Pratt for an MFA, right?

KOREN: Two years. part time. I got an MFA in art education, although I did a lot of work in printmaking, drawing, and painting.

GEHR: Did you have a mentor there?

KOREN: Yes and no. I took a few courses with Dore Ashton and got really friendly with her, so I would say she was my closest mentor. I got friendly with the painter Robert Richenburg, who taught me interesting things. And I learned a lot about drawing from Mercedes Matter. After I graduated, I immediately got a job at Brown. I felt that at least I had something under me and could do anything creatively without having to scrabble around. I’m a child of the prosperous middle class, and I was uncomfortable. I could drive a taxi just as well as anybody, or I could be a bartender, but I didn’t want to. It would have been the same problem as working full time for the Columbia Press. There’s nothing left in your brain at the end of the day.

GEHR: So you like teaching?

KOREN: I love teaching. I left it with great trepidation and sadness. I was there from 1964 to ’77. After I resigned in ’77, I was an adjunct until quite recently.

GEHR: Did you ever teach cartooning?

KOREN: No. I didn’t want to. I have this sense that you can’t teach it. I mean, you can teach the nuts and bolts of it, sure. And you can teach setting up a situation and telling a story that way. That’s all teachable. But what’s underneath it all, that bedrock of humor, alienation, and whatever is the engine of humor, satire, resistance, and subversion, you can’t teach that. If somebody doesn’t have it, there’s nothing you can teach them. It’ll be like an empty shell.

GEHR: Do you favor any particular theory of humor?

KOREN: They all have a little something to them, like a sense of displaced anger or schadenfreude. I sort of know how things work, and I can see how to make an idea better. But if that idea really comes from some magical, wonderfully unexpected place, how do you explain that?

GEHR: What made you decide to quit Brown?

KOREN: Divorce. My ex-wife moved to New York and the kids went down with her. I was living in Providence and was commuting back and forth to see them, sometimes twice a week, from Providence, along with teaching and trying to be a cartoonist. The agent Ted Reilly took me on, and he was getting me all kinds of illustration work, mainly advertising and other commercial stuff. I just couldn’t keep up with it all. At that time, The New Yorker was buying a lot. I was selling forty or fifty drawings a year. I found that I was giving the teaching short shrift, and something had to give. I was killing myself with all this commuting, and I had no place in New York. So I said OK, this is nuts. I’ll move to New York and just commute up there once a week and teach two or three days and maybe that’ll be better. But it really wasn’t. If anything, my work life got more intense, so I was stressed out a lot again.

GEHR: When did you move to Vermont?

KOREN: I bought this place in 1978, partially because some good friends whose kids were the same age as my kids had a place nearby. I bought it almost on a whim, because I just wanted a house. It seemed nice, and the village was quite appealing and, at that time, there was no construction around it. It was like an English or French village. It was very insular and isolated. It’s become a bit more of a suburb than I would like it to be, but here I am.

GEHR: Do you feel like a local or an infiltrator at this point?

KOREN: Oh, I think I'll always feel like an outsider. There’s no way I’ll become a Vermonter. They’re very insular, very proprietary, especially in this part of Vermont, which is exceptionally rural and somewhat isolated from the rest of the trends going on in the state, like around Burlington, where there is massive suburbanization and development. Curtis [Koren's wife] and I oozed up here full-time in ’87. It wasn’t even a decision. We backed into it.

GEHR: A lot of your work seems to explore the interactions between locals and outsiders.

KOREN: A lot of my work is about the interface between these two parts of the world that I’m sort of half in and half out of.

GEHR: There’s a real tension there.

KOREN: There is, but less and less so as more and more people like me move into Vermont. But this is the real Vermont. The Vermont profonde, as the French would say.

GEHR: I noticed Floyd's General Store, which has popped up in many of your cartoons, right down the road.

KOREN: Every morning his cronies all show up and sit around that stove and bloviate. He’s a bloviator, a real interesting guy. Al Floyd, fire chief at Randolph Center. So I get to know these guys, get in their brains, and kind of get to like them. Or not, as the case may be.

GEHR: You've called Saul Steinberg your mentor. Did you know him well?

KOREN: He wasn't so much a personal mentor as a model of how to work. His literary and visual meldings are an extraordinary achievement, a feat of artistry. He was unusual, unique, and a genius. And he was nice to me.

GEHR: How so?

KOREN: Just kind of friendly. He invited me to his studio a couple of times just to schmooze. He was open and encouraging. [Steinberg Voice] "I like what you are doing. You have a very interesting notion of America. America’s a strange place. The problem with the country is there are no girls." Of course, I knew exactly what he meant. The rural woman tends to be not terribly attractive, charming, worldly, or anything. Of course there are some, but look around. There are these large, overweight, helmet-haired creatures who do everything they can to make themselves unattractive.

GEHR: It's still difficult to conceive that Steinberg was doing "high" art in the cartooning format.

KOREN: Well, therein is the problem to kind of mull over: the notion of high and low art; of humor, satire, and the gag cartoon. And/or the other side of it: telling a story in the simplest means possible. How is this different, in a structural way, than [Paolo] Veronese unfolding a narrative in a single-panel format? As in The Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto, where he tells you what went on, but it’s all frozen in time. It’s like that great Arno cartoon, "Back to the old drawing board." This plane just crashed and the ambulance is rushing to it and people are [panicking] –and there’s a guy with his plans, his notes. But the way it’s constructed – I won’t compare him to Veronese, but I will – some of the elements depicting what was happening are exactly the same, and the drawing is equally as refined and individual and inspired. You can tell a Veronese because of the brushwork, line work, and structuring of the pallete. It's the same thing with an Arno. So where is the value system of high and low? Is it in the ambition that this is a religious painting and this is just a – well, that’s old hat by now. That’s the French Academy. The first time that caricature and satire in this kind of drawing was ever considered – as it should be, of course, because I’d like to be important – was by [Charles] Baudelaire, who wrote about Daumier in the same way he was writing about other painters.

GEHR: Your own cartoons tend to include more rather than less. How do you edit yourself?

KOREN: I love to elaborate, because that’s part of the story being told. There are little nuances, things in the background that kind of relate to, or illuminate, the actual action I want to focus on. It adds to it. But it’s a fine point, because if it’s too fussy, too busy, then it gets too unfocused and you tend to lose certain aspects of what I want to say about the interaction of these two people. I think of the panel like a theater director, or a playwright, would, because I'm unfolding a drama. I cast these people to be who I want them to be, and then I have a costumer come in [laughs] and a scenic designer and a lighting director and I put it all together. I don’t think of it that way normally, but that’s sort of how I’m operating. I want the action, the emotion of the moment, to be profound, clear, and also funny. So how do you do all that? It’s like a juggling act, and I relish it. It’s problems I love solving.

GEHR: Was there ever a point where you decided to replace solid outlines with bristles and fur?

KOREN: A lot of them start out with outlines. The rough drawings are very quick and fresh, and I try to keep the dynamic part of it going. Lee [Lorenz] has this incredibly vivid, lively style, and I want to keep that in my own work, as well. Robert Blechman is another one who only uses two or three lines, all very spare, and each one considered as carefully as one would consider a major military move. According to a mutual friend, he looked at one of my drawings once, and kind of shuddered, and said, "All those lines." [Laughter.] And I keep thinking about that because, yeah, there are a lot of lines – and a lot of artists who have opted for one style or the other, or something in-between. And with [Gilbert] Shelton, I mean, my God, it’s everywhere. So I don’t – I never think of there being a contradiction between an outline that’s somewhat developed and one that’s a little tenuous and uncertain. I’m always uncertain. Part of it is almost a fear of commitment, in a way. I’m an artist who fears that.

GEHR: Do you have an alter ego in your drawings?

KOREN: Yeah, I often put cats in as the observer, and I think that’s who I am. I’m the narrator, an observer talking about what’s going on inside the main action. Oh, and when I have people around they'll be someone like myself sitting around in the back, just observing – like Hitchcock put himself in his films.

GEHR: The animals you often use are surrogates as well, probably.

KOREN: An animal is very much a surrogate. I was thinking about this today, actually. I did this cover with animals [October 22, 2012], and if I had done it with humans, it wouldn’t be funny to begin with – to me, at least. But somehow they can have the same emotions people who are about to start a race have, or the same expressions and intensity. If it were people, you’d look at it and say, "So what? That’s the way people are. What’s new?" But somehow this turns it on its edge, or upside down, and I’m not sure why. This is where I’m really against an understanding of it. I know I use it, and I know that I’m satisfied with it, in a kind of unclear, almost unconscious way.

GEHR: What other times do you use animals instead of humans?

KOREN: I enjoy drawing humans as well. In a way, it just comes down to intuition. If there are some ideas that wouldn’t be funny one way or the other, I just kind of know in my bones that this is the way it ought to be. Because I have tried them back and forth sometimes, just to see if it works. I just got an OK for one that uses birds. It has to do with political correctness and all this turmoil about where our food comes from. It makes perfect sense with birds. But if there were a mother and a husband, and he’s brought something home from the market, and she’s questioning whether it came from the food co-op or the supermarket, it wouldn’t work! It wouldn’t be as pointed, sharp, and driven as a bird with a giant worm being asked, "Wait – did you procure that worm humanely?"

GEHR: What’s your cartooning schedule like?

GEHR: What’s your cartooning schedule like?

KOREN: Well, first I go to a fire [laughs] and then I look at email. I’m a very unstructured fellow. It depends on whether there’s a deadline or something I really have to do. But usually I just go into the studio in the morning, futz and putter around, and get up to speed. Warming up. Doing a few laps around the studio: a lap to the email, a lap to some manual, physical things I’ve got to do like filing – the stuff a friend of mine calls "administrative caca." And then I start drawing. If I’m working on roughs, I’ll do that for two or three days at a time. It depends on whether or not I’m actually firing on all cylinders. Sometimes it requires just sitting there, and then it happens. And sometimes one sits there for hours and nothing happens, no good ideas. It’s a defibrillation of the brain, being funny. And sometimes one thing leads to another through a process of association and free association and mental disassociation. I don’t know. It’s often a funny netherworld of gauziness where these things just happen. What did Arno say to a woman? He said, "Madam, these ideas just don’t happen. They come from the long hard hours sitting and working." And there’s that, too. With OKs I’ll go right to work and not futz around too much. If I’m in it, I’ll just stay in it. I’ll work for a while, go out and do something, and come back. Basically, I’m there from morning until night, with interruptions along the way to take a bike ride or go for a run. In the winter, I’ll take my old cross-country skis and go off into the woods.

GEHR: What’s your batch like these days?

KOREN: Not much. I tend to edit myself more, than I did. So I end up refining it to maybe five or six roughs. Maybe seven, but not much more than that. And for me, it’s a great achievement to get six sharp, focused, viable, and funny ideas I hope will seem that way to [David] Remnick and [Bob] Mankoff. Then I sit back and wait to see what happens to them. Off you go! Have a nice trip! Come back safe!