From The Comics Journal #190 (September 1996).

This is my second interview with Barry Windsor-Smith. My first was conducted in (approximately) 1970, which would’ve made me a starry-eyed 16-year-old and (the pre-Windsor) Barry Smith a comparatively awesome 23-year-old grown-up drawing for Marvel Comics (and with an exotic accent yet!). I remember absolutely nothing of that first interview except for the atmospherics: Barry sitting on the floor of a dimly lit, rather plush Manhattan apartment, stereotypical New York street noise wafting in through the window, and me hanging on his every word. In retrospect, it must’ve seemed to me like the quintessential (not to mention, in retrospect, the oxymoronically) bourgeois/bohemian artist’s garret. (Barry told me recently that it was a friend’s apartment and that he never could’ve afforded such a place then.) Barry was gracious enough to give me a few drawings for a fanzine I published then, and we kept in touch for a couple of years, but eventually lost touch and hadn’t talked to each other until, literally, I contacted him about this interview last year.

Throughout those 25 intervening years we both apparently kept an eye on what the other was doing. Unbeknownst to me, Barry was reading the Journal through the ’80s (and tells a pretty amusing anecdote about the time he expressed approbation of the magazine to Jim Shooter). My own interests and aesthetic preoccupations moved me in a very different direction from what Barry was doing. I followed his Fine Art period when he manufactured prints and posters through his own Gorblimey Press, noted with insouciant horror his return to Marvel, was further mystified by his alliance with Valiant and had casually written him off as an unfortunate example of a superlative craftsman who was too smart not to know that he had made Faustian pacts with not one but several devils in a row. This saddened me because I remembered his kindness to me as a kid, remembered enjoying his growth as a stylist on Conan in the ’70s, and remembered respecting his move from Marvel to his serious pre-Raphaelite inspired painting. “Ah well,” I thought, “another artist who could’ve been a contender.”

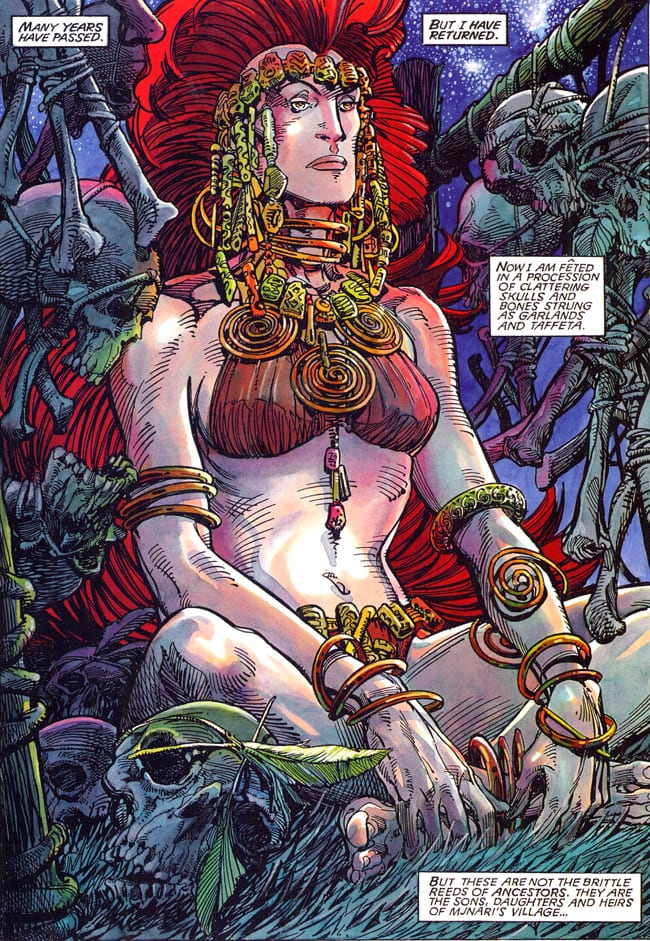

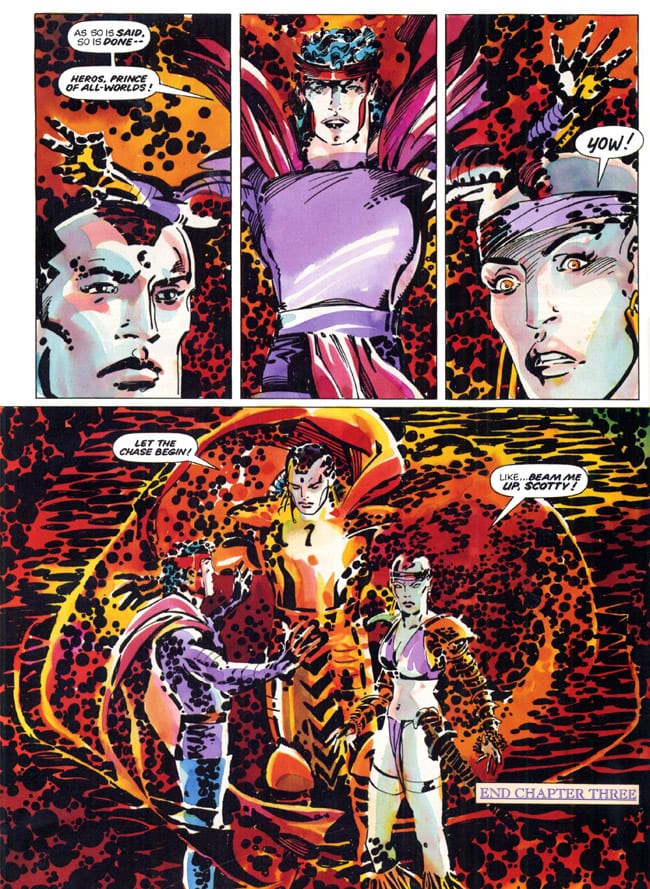

Well, the good news is that he is indeed still a contender. His new book Storyteller is not just the best work of his career but, in my opinion, a major step beyond anything he’s done before, making his journey from corporate work-for-hire artisan to more idiosyncratically expressive artist one of the most circuitous in the history of comics. Admittedly, the look of Storyteller is off-putting to someone like me who has had it up to here with the infantile formalistic trappings of mainstream comics, but once I was able to set aside my prejudices (entirely justified 99 percent of the time, mind you) I recognized that Storyteller is a) his most personal work to date and b) essentially a comedy, which makes all the difference in the world. It is funny, charming, ribald, parodic, great fun, and beautifully drawn.

Originally I had intended to do a standard Journal career retrospective, but Barry preferred to have a freeform conversation about comics in general and his comic and career in particular and to let the conversation take us where it would, and that’s just what we did. The resulting discussion should prove unique because Windsor-Smith’s point of view is, uniquely enough, that of a second-generation comic book artist whose career was spent mostly in mainstream comics but who’s too self-aware and talented to continue working in that “tradition.” He’s now in the process of finding his own voice and that’s all to the best. I’ll try to get back to him in 2020 to find out how he’s done for himself. — Gary Groth

TOGETHER OR NOT

GARY GROTH: Just before I turned on the tape recorder, you said you didn’t feel real “together,” and it seemed to me that this would be the point in your career, doing what seems to be the best as well as the most personal work of your life, on the verge of a critical and commercial success, that you would feel most “together.”

BARRY WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, the commercial bit we’ll have to see about, but yes, I think I’m definitely doing the best work I’ve ever done. I think why I feel I’m untogether is ... If this stuff works out there in the field, if it’s a commercial or critical success, hopefully both, then I think I’ll feel perfectly together and I’ll be happy about it. But I’m drawing and writing and inking and coloring the fifth book right now, and I’m kind of in a vacuum.

Somebody’s always going to find something nice to say about my work, I guess, but I’ve received nothing but compliments from friends and associates: I need to hear what my critics have to say. I’ve got this hope, it’s like a really idealistic dream that this is going to work, but there’s no proof of it yet. Sometimes during the day if l get a good idea or I get something down just the way I want it to be and it makes me laugh maybe, I think, “That’s a good piece of stuff I just pulled off there,” then I feel good about it. But I tell you, there are times at 3 o’clock in the morning and I’m sitting around, because I’m a pretty bad sleeper, and I’m thinking, “Christ, what have I let myself in here for? This is really on the edge.”

So that’s what I mean by being untogether. I have faith in myself to a degree, I have so little faith in the public nowadays I have to say [Groth laughs], because I see what sells, what’s been selling for the past decade. Of course everything I’m going to say is obviously my personal opinion, but just so much of the craft of this industry has just gone down the tube, and somehow, by wicked circumstance, the sales have gone up — even though it’s been going in the dump for the last year or so. But the stuff I’m producing is the antithesis of what would be a grand commercial gambit by the standards applied today. I think it’s well written, I think it’s well drawn, it has a literary edge to it — it’s all that shit that don’t sell, you know [laughs]?

GROTH: Yeah, you re definitely not appealing to the quintessential fanboy who wants The X-Men.

WINDSOR-SMITH: The X-Men, yeah, or the other stuff. I guess it’s all the same thing — all the X stuff, whether it’s from Marvel or Image.

GROTH: Basically sex and violence for kids.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right, on a very immature level. I’ve got violence in my books, but —

GROTH: [Sarcastically]: Unfortunately you’ve got humor, too [laughs].

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, see, that’s a big drag. There’s a drawback right there — it’s funny! So I’m really asking for trouble here.

GROTH: As an artist I’m sure you believe this, which also makes it a little bit more puzzling why you’re concerned about what the reaction is going to be, but as an artist don’t you think that ultimately you have to please yourself and that anyone else’s opinion is really beside the point?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, for one thing, “art” is such a massive term. I guess it’s just a personal thing with me that I feel if l can’t please other people, it doesn’t please me. Now, that’s not to say that my goal is to please other people. But I don’t do this for myself, you know? I certainly like to bathe in the glow of the title “Artist,” but I also consider myself an entertainer — not that that is my sole interest, either. I’m not here just to entertain; I’m here to do all sorts of things. But if I don’t capture my audience — and if I fail at either making somebody laugh or making somebody think about something, or just having somebody enjoy a drawing for its own sake or the color combination — if it doesn’t work for them, then we can call the product a failure; it doesn’t necessarily mean that I failed as an artist but simply that I did not succeed as an entertainer.

So no, I’m not out just to please myself. Not in the least. I think that’s one of the reasons why [I’ve had] such a hard work ethic over these years. If it was just for me, then gee, my work would be a whole different animal. I think there are people in this field who do it for themselves, and fuck the rest. But I’m referring people in the commercial side of the field. But somebody like Chester Brown is doing his work for himself. He’s in a whole different field — he’s not writing The X-Men. And one can’t say his attitude is, “Well, if you don’t like it, fuck you.” I really think that he genuinely 1) wants to explain himself, and 2) hopes that somebody, if not being entertained by it, at least can grok what he’s saying. There’s a value to that. It’s all about communication. There’s a good word. If my stuff fails to communicate, then it has failed, no matter what I did or how I did it.

GROTH: But of course that could be less your failure than the public’s failure.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Absolutely. The way I’m looking at it now, because I really do have a bit of some unsurety about the public, if I can’t make somebody laugh with this stuff, well then, they’ve got no fucking sense of humor, you know what I mean?

GROTH: [Laughs.] Right.

WINDSOR-SMITH: [Laughs.] Fuck ’em all!

GROTH: I think that’s a healthy attitude.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah.

COMICS AND ART

GROTH: One thing you said in an interview that you gave which was not to my knowledge published was, “I can’t draw comics, or I can’t make comics, and be a serious artist at the same time because they’re such wholly different processes.”

WINDSOR-SMITH: I think that was published. I forget who I said it to. But it’s something I certainly believe right now also.

GROTH: Can you explain what you mean by that dichotomy between making comics and being a serious artist? Why do you feel that they’re mutually exclusive?

WINDSOR-SMITH: I think that probably either you have mis-remembered it, or I mis-said it at the time. But what I really should have said, which is a slight difference with one single word, is a “painter.” Because at that time — that probably came from the Gorblimey Press years — and in order for me to be able to transform myself from a fairly good comic book artist into a person who can create large easel works, as I call them, the difference in thinking, the whole difference in process, is absolutely phenomenal. There is simply no comparison. But just because a guy can drive a car 200 miles per hour at the Indianapolis raceway doesn’t mean that he can fly a plane at 200 miles an hour. You’re doing essentially the same thing, going from A to B very fast, but it’s a whole different process of thinking, action and reaction.

When I first wanted to get back into comic books after 10 or 11 years of Gorblimey Press it was simply because I wanted to tell stories again. But I couldn’t do it. I foundered totally. I had put comics totally out of my mind. The only connection I had with comic books for about 10 years was reading The Comics Journal.

GROTH: [Laughs.] No wonder you couldn’t draw comics!

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, actually I found it very depressing. I don’t know if it was so much shit going down all the time, or you were just raking it up all the time. [Groth laughs.] But I was thinking, “Christ, what is this bleeding industry coming to?!” But, at any rate, I simply couldn’t locate the skills I once had. I couldn’t cartoon any more. That was an absolute nightmare for me. Over 10 years I had to learn how to really draw, and the whole process about cartooning had gone utterly out of my head. Nowadays, I’ve been drawing three different titles continuously since October or November of last year, every day, that’s all I do. All I think about is continuity, pacing, staging, all the elements that make a comic book for better or worse. And you have to keep them in your head all the time. Eventually it becomes second nature, thank God, and now I can think that again.

But way back in the mid-’80s when I grabbed some old yellowed Marvel comics paper and tried to think sequentially and draw dynamically I found I couldn’t. I just couldn’t make it happen. So my good friend Herb Trimpe bailed me out on that by letting me work over his layouts for Machine Man. Then I picked it up again really bloody fast, a little bit too fast for Herbie because by the second or third issue I’d be erasing his layouts and putting in my own work. [Laughs.] But it was really like a whole re-learning process because I had become a civilian for a decade or more — I became one of those people who can’t understand comics. Do you know people like that? Who simply don’t understand the, process, the left to right, you read the balloons in sequence...

GROTH: I don’t know if I know people like that. I know people who don’t read them, but I don’t know if I know people who can’t read them.

WINDSOR-SMITH: There are many people who don’t read them. But I’m talking about people who actually can’t fathom the process; I have civilian friends who’ll give it a try because they know me, but they have no understanding of the process of reading a comic book. A girlfriend of mine who was a fine artist, a sculptor and a painter, hip to the arts, tried to read my Weapon X... [Laughs.] I’ve just put myself open to massive criticism: “Nobody could read your bloody Weapon X, Barry!”

GROTH: [Laughter.] I wasn’t going to say anything.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But she tried to read it because she wanted to know what I was up to. And she kind of looked at the page as a whole rather than starting top left. She looked at all the pictures at once, and gazed at all the balloons, probably from the middle outward or something. It’s a bizarre thing! But for some time around just 10 years ago I found myself in a similar situation of being unable to identify the graphic cues used in narrative storytelling. Nowadays, I’m glad to say, it’s as natural as breathing.

GROTH: I don’t understand the difficulty someone would have reading a comic. Do you have a theory as to why a literate person would have such difficulty?

WINDSOR-SMITH: I don’t have a theory; it’s just an alien process to some people. But the reason why I brought it up was my renewed efforts to create a sequence of drawings left me baffled, even though I had literally drawn scores and scores of comic books in the years beforehand. But I just went through this 10-year process of exorcising it, getting it all out of my system, out of my mind. So from that experience I learned a little bit about the straight civilian perception of comic books. And that gave me some perspective to realize why our field of endeavor is so often misunderstood. Along with many other things, like that guy [Greg] Cwiklik brought up in his “Inherent Limitations” piece, which I think was really well done — yes, there are lots of reasons why comics aren’t acknowledged in America...

One very essential re-perception I had at that time was just how chaotic comic-book images were, how literally ugly most of the pages and characters and colors were. By the mid-’80s, as I began looking over the current work published by Marvel I was appalled by the lack of harmony and synchronicity in the art itself. I had become highly sensitized to the aesthetics and poetry of the visual arts and all other forms for that matter, and, I tell ya, to pick up the latest Incredible Hulk, Spider-Man or what-have-you and to try to make sense of the cacophony of it all, the hopelessly bad drawing, the garish, misapplied colors and the ineptitude of the words just cluttered everywhere and anywhere — most comics just looked like colorful garbage dumps to me. No wonder the average adult cannot understand their appeal — comic books can be truly ugly and, of late, ugly appeals to children more than beauty and harmony does. Thrash metal and lukewarm punk has replaced the three-part harmony of the Beatles or even the Stones for that matter. All I could see in these publications was a riot of immature ramblings! And it’s just a bleeding American comic book I know but, quite frankly, I find such products, aimed at children, to be grossly disturbing on a level far more sensitive than the moral majority could ever comprehend.

GROTH: I have the same reaction not just to comics but to much of contemporary pop culture, but what you’re describing practically defines postmodernity, I think: fractured and incoherent displacement of traditional modes. Not that structural experiments cant prove artistically fruitful, but when they’re not applied appropriately and become a standardized approach by tenth-rate hacks, they prove the worst of each world: avant-gardism in the service of the same old shit. Art Spiegelman eschewed his more experimental mode when he did Maus, for instance, because he thought it wouldn’t be appropriate.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Now, Maus was so easily read. It was that box format of panels, and three pages into it, the formula was there for you, you didn’t have to think about it any more, so the narrative was so simplified, and of course the imagery, as Cwiklik pointed out and everybody knows, was brought down to a minimum of understandable images. But it was a very raw minimum. And I think that allowed certain civilians to be able to wade through it. The subject matter is something that everyone knows about, but if it was a science fiction book equally as well written, equally as simplified in its drawings, but involved space monsters, would the civilians have looked at it? Would it have won a Pulitzer Prize?

GROTH: The content was there; when people opened the book up they knew what to expect, I think, and that must have helped them get into the medium.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah. But ask yourself, if Spiegelman had done it on something that wasn’t so appealing to the public...

GROTH: Yeah, I don’t think there’s any way it would have achieved either the acclaim or the readership.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I doubt it very, very much. So it’s like a false victory for all of us working in an unrecognized field, a comic book was awarded a bloody Pulitzer. Yes and no but, not really.

GROTH: Right.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Have you seen Joe Kubert’s Fax from Sarajevo?

GROTH: I’ve seen some pages from it, I haven’t seen the whole thing yet.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, I haven’t either; I just saw the pages in CBG. I didn’t read the article or the interview about Kubert, but an immediate comparison has to be made, you can’t help yourself, with this serious subject matter of Sarajevo, and Maus. I ask myself, “Would Joe have done this if not for the success of Maus?” And Joe Kubert’s style was one of the things that disturbed me awfully about looking at those pages. Spiegelman’s style with Maus was Spiegelman’s style; he didn’t have to re-tool and re-fit himself. He didn’t have to downgrade, didn’t have to upgrade. That’s the way he does things, and it’s certainly the way he saw it and it came up with a plum. In the case of Kubert’s Sarajevo as I say, I don’t want to criticize the work because I haven’t read it, but I’m looking at the pages and I’m thinking, “Blimey, this looks like Our Army at War.” Right?

GROTH: [Laughs.] Right.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Because Kubert is such a stylist. And also he’s going for the same kind of panel things that he’s done over the years, which is his own style, and it’s very commendable — it’s not Jack Kirby window-type panels. It’s insets and stuff like this. So I’m looking at that and I’m thinking back to my girlfriend who couldn’t make any sense of the Weapon X stuff: “Why is that panel laid over that one?” “It’s just a style, that’s all.” “Oh, OK then. I’ll try and read it.” I actually had somebody look at one of my pages once, a Conan page from “Red Nails” when I was still drawing it in the ’70s, and she absolutely adored my work — she was the sister of another girlfriend of mine, she was about 18, in college or whatever, a smart kid — and she was looking at one of my original pages, a big drawing of Conan, and she asked, “Why does he got all those lines all over him?” And I said, “What?!” I was across the table so I wasn’t really looking at what she was looking at. But she said, “Well, there are lines all over his face. What are they?” I leaned over and I said, “That’s the way I draw it.” She didn’t get it. What she thought they were, were tattoos. You know that funny queer inking I used to do in those days? She thought that those lines on his face were not part of the construction of pen lines I used, but tattoos or something. She couldn’t get it; she couldn’t figure it out. I was in no mood to explain it, so the whole thing kind of shoved off. [Groth laughs.] But that was another example of how even the smartest or the most commonplace of people will look at some form of stylism and not be able to recognize it. Now, this was a stylized visualization of a man — you knew that because he had eyes, a nose, there was hair on top of his head — but what she saw were tattoos on his face, and on his arms and legs. He was tattooed all over the place! No he wasn’t— he was drawn by me! [Groth laughs.]

Now, as I say, there was nothing wrong with this girl’s understanding; she just was faced with an alien art form.

GROTH: That would tend to prove that people have not assimilated the conventions of comics.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yes.

GROTH: There’s a certain suspension of disbelief in any artform — if you’re watching theater, you don’t sit there constantly thinking, “These are actors on a stage.”

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right — then you’ve blown it.

GROTH: Right. And that just tends to prove to me that people have not assimilated the vocabulary of comics and allowed themselves the distance that the necessary artifice of any artform requires.

WINDSOR-SMITH: The entire bleeding industry hasn’t put anything out over these 50 or 60 years that is going to attract the civilian to want to understand, to care enough about it to say, “My goodness, look at this: this is a whole language here that I have never even known about. And it’s an American artform — let us embrace this.” Because, as Cwiklik said — and it’s not as if he’s the first one to say it by any means — “Who the hell would give a shit?!” [Groth laughs.] The content of American comic books is by and large just low-grade garbage. Who would want to get themselves soiled with this kind of thing?

Big digression. So back to the Fax From Sarajevo. I’m looking at these pictures and I’m assuming that Joe’s sincerity is deep and profound. But did Joe ask himself, “Should I draw this in my Sgt. Rock style? What is my style for Sgt. Rock? How understandable is it, except for kids who grew up with it?” This stuff is supposed to be pathetic, it’s supposed to be horrifying: the little girl getting blown up by a Joe Kubert explosion. I think that’s what I’m trying to say: It’s a Joe Kubert little girl, and it’s a Joe Kubert explosion. And there’s a sound there that’s a Joe Kubert sound effect: Ka-boom!, or some such. It just left me confused.

GROTH: I had the same exact reaction.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Good! Well, not good for Joe, but good for the point.

GROTH: Yeah, and I respect Joe very much, and I respect his drawing. And I certainly respect the kind of seriousness he wants to bring to the project. But you know, Spiegelman is somewhat of a stylistic chameleon. He tailors his approach to every individual project.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I did not know that. I’m not really that familiar with Spiegelman’s work.

GROTH: He tried to do Maus earlier in an entirely different style, a much more detailed and labored approach, which he later deemed inappropriate and he really worked hard to get that simpler style.

WINDSOR-SMITH: This is actually documented, is it?

GROTH: Yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH: That’s very interesting. See, I thought that was just serendipity — of a natural style that fell into place at the right time. So he actually worked on that.

GROTH: Yeah, I think it was a very calculated choice on Spiegelman's part — and of course it worked perfectly, I thought.

GROTH: Yeah, I think it was a very calculated choice on Spiegelman's part — and of course it worked perfectly, I thought.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Then I congratulate him for that.

GROTH: But the difference I think is, Joe's drawing is subordinate to his idiom, and I’m not sure the idiom he’s engaged in for 50 years is appropriate to a story about Sarajevo.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, if he’s done that in Our Army At War, then how sincere can it be? You know? I think Joe wrote this too, right?

GROTH: I think he wrote it in the sense that he sculpted it from faxes from his friend in Sarajevo.

WINDSOR-SMITH: That’s right, I just read that, of course — the guy with the outrageous name, Magic something…

GROTH: Right. But I think you could say that Joe was the author in the sense that he shaped it.

WINDSOR-SMITH: All right, then I would like to presume — and again, I didn’t read any of the balloons in those reproductions — but I would like to presume that Joe scripted this thing without the outrageous hyperbole that “Our Army at War fighting dinosaurs” had. Now, say it’s pure assumption on my part, but you’re going to be hip enough to say, “I can’t write this with lots of exclamation marks after everything. I’ve got to adapt for the sake of the content of the story.” And yet here I am looking at the drawings and I see a Joe Kubert explosion. And there is no sense of horror in it whatsoever. Because frankly I saw Sgt. Rock get blown up a load of bleeding times, and he hasn’t died, you know? [Groth laughs].

GROTH: Yeah, I remember a drawing of the family with a little girl, the mother and father, and there’s a romanticization to his depictions.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Absolutely. There was that one shot — the group of the family huddled together — and the guy looks exactly like Rock except he’s going bald, and of course Joe draws the most luxurious women.

GROTH: Beautiful women.

WINDSOR-SMITH: And he tries not to, but he can’t help himself. So here is a man who is absolutely burdened by his own style. So if he can’t step outside of what he does, perhaps he cannot be recognized as a serious storyteller, because he has a style that will not enable it. Now, just in this tiny topic of Joe’s latest work, we’ve got a whole area there that opens up so much criticism about the value of comics and what they can and cannot do.

An interesting possibility is that perhaps the serious content of Sarajevo might attract favor from critics unfamiliar with mainstream comics as a whole and, because such art or literary critics have not enjoyed Joe’s Our Army At War etc. from all these years he’s labored in our field they won’t have the same reaction we do: they won’t say I’ve seen this all before,” so perhaps an overused graphic stylism of Joe’s may be perceived as inventive and intelligent by a fresh pair of critical eyes. Could happen.

GROTH: Yeah, I sometimes wonder if knowing as much as we do about comics — too much, perhaps —could prejudice our eye. But, on the other hand, it almost seems to me that the difference between what we’re seeing in Joe’s work on Sarajevo and what we’d like to see is the difference between Hollywood and European films.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah.

GROTH: And if you look at Andre Wajda films from the ’50s, the people in there are ordinary-looking, they’re not Burt Lancaster and they’re not Kirk Douglas, they’re just the most ordinary human beings you’ve ever seen dealing with obstacles, exercising a degree of courage and so forth, and one of the problems with Joe’s work is that the characters and context look like they came out of Hollywood.

WINDSOR-SMITH: They look like Hollywood heroes and heroines. This is what was required of Joe when he started at DC. Surely Joe’s first scribbles when he was 4 years old didn’t look like the Joe Kubert we know today. So at some point he developed that style, it got stronger and stronger... I think it was actually Viking Prince which was just glorious, and very much Kubert — you can see it’s Joe Kubert even today, even though that was 30 years ago — and that was the beginning of this fluency that he has with the brush, something you can’t get around. But when talking about visuals here, what if Joe said, “Oh, fuck this brush stuff. I’ll ink it with a crow quill. Let’s see if something more telling comes out; let’s see if I can draw something — no pun intended — out of my art that I can’t do because I’m capable of drawing and inking three pages a day of high stylism.” I would have been thrilled if Joe had stretched himself. If he thinks that stretching himself is putting down Sgt. Rock or whatever the hell it is that he’s drawing nowadays, and picking up Sarajevo, then he’s missed a point.

HOOK, LINE AND SINKER

GROTH: This brings us to a very interesting point about the whole history of comics. It seems to me that artists of Joe’s generation —people like Alex Toth and Gil Kane, the whole pantheon of superior artists — were cranking work out on such an industrial schedule, that they couldn’t really tailor their work to their own personal vision or personal expression so much as they simply had to draw as well and as quickly as they could; and since they were told what to draw and what they were told to draw was basically adolescent in nature, their styles either conformed to that adolescent context or never coalesced with it. And I think that has had a deleterious effect on them as cartoonists and on the artform.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Absolutely, I agree. That’s what you were saying to Gil [Kane]. And Gil of course agreed with you. To be perfectly honest, I didn’t finish [the interview you did with Gil], the last four or five pages. I just couldn’t go on — it was like reading one of the most depressing novels. I was thinking, “All right, I know how it’s going to end, I don’t have to slog through the last few pages.” [Groth laughs.] Gil, to me, is absolutely the prime example of what you just said. And here is Gil bemoaning that he hadn’t done anything, or that he still, at his age, in his twilight, wants to do something of weight, something grand, something that’s going to be remembered. And by Christ I understand his needs. I mean, my thoughts and feelings are with him for that, you know? But here is a guy who succumbed to every bloody cliché about the publishing industry — let alone the clichés in the comic book drawing side of it. And there’s all these reproductions of the books that he read, which I thought was so… Frankly I found it pitiful. Did he ask you to reproduce those covers?

GROTH: No, no, in fact that was my idea. We were trying to figure out how to illustrate parts of the interview that were almost un-illustratable.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I got you, OK.

GROTH: And I pulled those out of my own library [laughs].

WINDSOR-SMITH: OK, that’s all right then. That’s actually better because I was thinking: what if Gil said to Gary, “Gary, Gary, you’ve got to publish the covers so that people know what I’m talking about.”

GROTH: No, Gil didn’t even know I was doing that.

WINDSOR-SMITH: OK. That makes it a lot less painful then [laughs]. But, here is this guy who’s describing all the work he did on himself and reading modern philosophy and then reading ancient philosophy, reading the two combined, reading great novels... And yet he’s turning out bleeding Captain Action.

GROTH: Yeah not being able to apply that learning to his work.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right, it’s simply like the ’twain never met. God, that is depressing. That is so... [sighs].

GROTH: Well you know, Gil is one of the few artists, I think, of that generation who has the self-awareness to know that.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah. Actually one of the lights that came on throughout the dark of that interview was that he knew the content of what he was saying. I think he could see the darkness and the irony of it. If he was saying this, and the interview was 25 years before, so rather than being in the industry for 50 years, he would be in the industry for 25 years, and he’s saying, “For the last 25 years I’ve done crap, no matter how much craft I brought to it, being able to draw a nice picture —I’ve done crap, it has no value, it’s not going to be remembered, it has no historical value whatsoever, just to my grandchildren...” If he said that 25 years ago and still had the energy to pull himself out and go on, then that interview would have been a reason for celebration. There would have been this guy saying out loud, “I’ve been wasting my bloody time, but I’ve got plenty of energy left and I’m going to turn everything around, you watch me.” So that was part of what made it depressing.

I wish... I don’t know what sort of circulation The Comics Journal has — I’m sure it’s not up there with Wizard —

GROTH: [Laughs.] You re right, there!

WINDSOR-SMITH: But I wish that some of the stuff, quite a lot of the damn stuff — this is going to sound like outright flattery and you know it’s not because I’ve got no ulterior motive to flatter you, Gary — but I just wish that you had some kind of a syndicate thing where you could publish ads for Wizard in exchange for them to do almost a public service to their readers by publishing some of the material that you put out. The Gil Kane interview comes readily to mind because there are so many people in this industry who are not going to know about that interview. Maybe they should. The young artists coming up who just have no idea about the potential of their medium because they aren’t using their humanism as a part of the medium. I forget where this was published, it might have been in your magazine, I don’t know, but Jean Giraud was talking about American comics and he said — and I’m probably going to slightly misquote him here, but in essence it’s correct — that American comic artists — and he was talking about the new breed, he wasn’t talking about Kirby or anybody like that — “American comic book artists don’t have any politics.” I think that’s exactly what he said. If you take that literally — and probably everybody did — it doesn’t make a lot of sense; it doesn’t mean anything. Like: ‘What, we don’t vote? Who’s to vote for? I don’t understand. I’m not 18 yet.” [Groth laughs.] But what he meant was, your Jim Lees and all this lot, their product hasn’t got anything to do with them, you know? There is no emotional investment.

GROTH: Well, more’s the pity, Barry: maybe it does.

WINDSOR-SMITH: [Pause.] ...Oh shit! [Laughter.] Scathing, scathing, you bastard!

GROTH: Well, I really wonder if consciousness hasn’t been reduced to that level, where Liefeld and Lee and the lot of them really have invested a certain amount of conviction into the pap they draw — which at least Gil’s generation didn’t because they had a degree of perspective.

WINDSOR-SMITH: We all make the same mistake — I do, you just did, everybody else does, so we can’t blame anybody for this — but we always say, “the Liefelds and the Lees.”

GROTH: Yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH… Rob Liefeld has nothing to offer. It’s as plain as bacon on your plate. He has nothing to offer. He cannot draw. He can’t write. He is a young boy almost, I would expect, whose culture is bubble gum wrappers, Saturday morning cartoons, Marvel comics; that’s his culture. Somebody was at his house and came back with a report: There is not a single book in his house — only comic books. I see nothing in his work that allows me to even guess that there’s any depth involved in that person that might come to the fore given time. I look at Jim Lee’s work, and the guy’s learning how to draw. He has some craft to what he does.

GROTH: Yes, right.

WINDSOR-SMITH: He is married; he has a child I believe: being married and having a child — facing life. Making a commitment to another human being. Creating. Co-creating another human being. This has got to put some profound thoughts in your head… Or does it? I don’t know.

GROTH: Well, in theory I would agree with you, but on the other hand, if you look at their work. Lee’s work is obviously more technically accomplished than Liefeld’s, but otherwise it’s conceptually comparable.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I can’t disagree. But what I’m trying to do is allow that... People who don’t have artistic inclination — and there are a lot more out there than there are people who do have artistic inclinations — they can get married at 19 and have three children before 25, you know? They can go through a hell of a life; they could be born in an interior of an urban slum. They see more of life before they’re 10 years old than a lot of people see before they die. They see fights across the street; they see the needle and the damage done; they see everything. If they don’t have an artistic bent, they could possibly grow up being really twisted by this — I’m not saying turn into monsters or anything — but have a real deep dissatisfaction with life, have no way to express themselves, express the hurt, or express outrage. The way of expressing outrage of course if you’re in that situation is to go out and hit somebody or rob a bank, or any number of goddamn negative things. But if you’ve got an artistic inclination, even if it’s on Liefeld’s level, there’s a way of expressing yourself. Here I’m going to go and put them both in the same bag again — but I don’t think the Liefelds and the Lees, I don’t think it has even crossed their minds that comic books can be a medium for intimate self-expression. They’re sort of like fourth generation from the Kirby type of comic, from the Marvel Comics entertainment shit thing that, it wouldn’t occur to them that this could be a medium for self-expression. And that to me is the biggest drag of all.

And that is what I think Moebius meant. Whether Moebius is drawing that bloke who flies on the pterodactyl or doing something more obviously personal, he has a personal investment in that, and you can tell he writes from the heart and the head, you know? Of course there are some people — me for instance [laughs] — I haven’t a bleeding due what he’s goin’on about! [Groth laughs] I get lost with Jean Giraud. But same old story: if you can’t figure out the bloody story, then just enjoy the pretty drawings.

GROTH: Getting back to what you said about Lee and Liefeld not knowing that this is a medium that is capable of personal expression: by “personal expression” you’re talking about something that can objectively be determined as meaningful, that has some determinant human relevance. But, I think we’ve reached a point, certainly in the comics culture, where people like McFarlane or Lee or whoever think that they are expressing themselves. I constantly read interviews with people who talk in grandiose terms about what they do, and then I look at what they do, and it’s just absolute pap.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I … didn’t ... know ... that. [Pause.]

GROTH: [Laughs.] See, things are worse than you thought, Barry!

WINDSOR-SMITH: Goddamn. I’m just reading the wrong magazines, Gary. Are you actually referring to the Lees and the Liefelds?

GROTH: Yeah, sure. If you read interviews with them, they really think that they’re committing themselves body and soul to this sub-literate drivel…

WINDSOR-SMITH: [They’re claiming] it’s personally valid?

GROTH: Well, in a specious kind of way. I think you and I would see it as essentially spurious. But, from their point of view and based on their educational level, they think that they are exercising personal expression. [Pause.] It would be interesting to call them up and ask them [laughs].

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah. Send ’em a fax.

GROTH: I think they’re obviously also thinking they’re entertaining, that they’re providing entertainment, but I also certainly think there’s a dimension there where they’re expressing whatever they’ve got to express; that they’re being artists.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Now I know from whence came your quick-witted put-down a few minutes ago. Maybe they are actually expressing themselves!

GROTH: Yeah. I mean, when they left Marvel, there were a lot of moral reasons bandied about, quasi high-minded reasons about creator autonomy and creator rights.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, I fell for that hook, line, and sinker. I really felt they meant it. And maybe they thought they meant it, I don’t know. I don’t know why they would deliberately lie, come to think of it, because taking the moral high ground like that isn’t going to assure more sales. It’s not as if the kids are going to say, “Oh! These guys are more moral than Marvel! They’re the Moral Comics group!” [Laughter.] So there’s obviously no value in lying about it; maybe they thought they were being moral. I thought they were. And I applauded them, because I wished I had the financial wherewithal — when I quit Marvel in 1973, I walked out with maybe $150. And I spent that on my first Gorblimey print, and if it didn’t work, I would have been working at the diner. But when they left, a lot of them had a lot of money, and I thought they were saying, “Now’s the time to strike out. Now’s the time to sever the chain and throw the iron ball away. Let’s go out and do it, guys!” I mean, I was so idealistic about them doing that shit — and then this whole bleeding thing happened earlier this year with Liefeld and Lee going back to Marvel … Goddamn, I wrote the most scathing letter that was supposed to be a public announcement sort of thing just putting down everything about this. I never had it published, I never sent it out— I think [my attorney] Harris Miller talked me out of it: “Barry, don’t send that thing! You’re gonna get sued! Then you’re going to make my life more difficult!” [Groth laughs.] I faxed it to Frank Miller. Frank felt exactly the same way, of course, and had already made his attitude public. I guess Harris didn’t get to him fast enough … But it seems to me that they said, “Hey look, all those publishers are making all that money — let’s make it ourselves, guys!” Which is a good enough reason I suppose, just as long as you’re up front about it.

DECLINE OF CRAFT

GROTH: Could you elaborate on your lament over what you perceived as the decline of craft standards? I assume you were referring to the Marvel-DC kind of material, and their devolution over the last 30 years.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, I think we all know there are declining standards. It’s probably true of a lot of different media, you know? But then again, we have pockets of the good stuff. Thirty years ago we didn’t have anybody in the field who could write as well as Neil Gaiman. But by the same token, it was... Jeez, I can’t even imagine myself saying that there was a higher standard 30 years ago, because there certainly wasn’t — in drawing, or in academic stuff like that. I don’t know. I’ll probably really put my foot in it by getting detailed.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, I think we all know there are declining standards. It’s probably true of a lot of different media, you know? But then again, we have pockets of the good stuff. Thirty years ago we didn’t have anybody in the field who could write as well as Neil Gaiman. But by the same token, it was... Jeez, I can’t even imagine myself saying that there was a higher standard 30 years ago, because there certainly wasn’t — in drawing, or in academic stuff like that. I don’t know. I’ll probably really put my foot in it by getting detailed.

GROTH: There is certainly a sense where even the middling artists — I don’t know what you want to call them, “journeymen” artists, if you want to be charitable, or “hacks” if you want to be uncharitable — but people like Dick Ayers and Don Heck, that sort of middle-level artist is no longer around, and what you’ve got instead are inept kids.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well there you are. You answered the question for me. [Groth laughs.] I don’t know if you know this, I mean, I know you made a goof once in public about Don Heck —

GROTH: Yeah, right.

WINDSOR-SMITH: But I can dig it, I can understand how you would have done that; I’d have done exactly the same as you — I’d have probably said that, and then I would have been very quick to apologize.

GROTH: Now he’s starting to look like a great craftsman! [Laughs.]

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, really! But Don Heck, once upon a time used to be a good illustrator. He’s got some comics work in print — well, of course they’re out of print, but the stuff has been published, I don’t know when, I can’t think of the dates, but it was certainly pre-superhero Marvel; I think it was Marvel comics, before they hit the big time with Jack Kirby and all that — and he had a wonderfully illustrative style: closer to top-quality fashion drawings.

GROTH: Yeah, he did romance work.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yes, right. I’ve only ever seen one of his stories, and I was utterly intrigued by the beautiful drawing, the use of blacks, wonderful feathering with the brush. He used to draw the most gorgeous women! I mean, highly stylistic of course, but in that 1950s fashion sense. There was this tiny signature on the splash panel: D. Heck. I saw this long after Heck had become a hack. But I thought, “This guy really used to sing,” you know? What happened to him? Now, it wasn’t as if he was turning out six books a month for Marvel, so his average quality hadn’t gone into decline. He was only doing Iron Man or something like that. So what the hell happened to Don Heck? Well, it could be anything. I don’t know his personal history, nor do you. But could it be that it’s the same old story — that he was told to draw like Jack Kirby? Same old bleedin’thing that you’ve heard me rattle on about endlessly in different conversations. Obviously he was trying to be dynamic, he was trying to do big figures and the dynamic Kirby poses, but it just wasn’t working, because it wasn’t him. So there you have another poor wretch who fell to the demands of the early Marvel.

Now, I don’t know if I’m correct about that, this is just a guess on my part. But in regard to the new foundlings in the field: when I came in in ’68, I was pretty awful. I didn’t have a hang on anything, really. But I had gone through art school; I did learn how to draw properly. I had lots of accumulated knowledge, even for just an 18-year-old. But my comics drawing really didn’t display that, of course. But at least I was coming from the right angle … Oh, that’s so damn qualifying, isn’t it? [Groth laughs.] At least I was coming from an angle that did, in its essence, have genuine knowledge behind it. It’s been said a thousand times and it’s absolutely true: You’ve got to know the rules before you can break them. That goes from Picasso as the greatest example, to Jack Kirby. Jack knew the human figure. He knew dimension and perspective. Jack had drawn in many different styles over his career. But during his heyday in the ’60s when he would draw a leg or an arm, you only knew it was a leg or an arm because it was either coming off of the shoulder, or coming out of the pelvis. If you separated one of his Captain America legs and put it all on its own, just one single leg, no foot, no pelvis, and put it on a blank piece of paper, you’d be hard pressed to figure out what the damn thing was! It would look like a sausage from Mars! [Groth laughs.] So there’s Jack breaking all the damn rules for his own vision. But as I say, the man had the bedrock of knowledge to do that.

It seems to me what we have today is people who have not learned but have adapted. They are adapting, they are using a style of some nature that is twice or thrice removed from “pencilers” who didn’t have much knowledge about drawing in the first place. It’s just so far removed from any sort of classical knowledge. I can’t remember any of these people’s names, all the young kids: they all go into one blender for me.

GROTH: Yeah, me too.

WINDSOR-SMITH: But if you imagine any one of them reading these words, if they should even think of reading The Comics Journal which is unlikely, and imagine, them saying, “Oh what a fuckin’ old fart that Smith bloke is! He thinks we should go to art school! What an asshole!” [Groth laughs.] So be it. But as I say, there are these little pockets of some very good talent. You’ve heard me mention Travis Charts, who does something in Jim Lee’s set-up. The guy is just fine! He has a real understanding. That doesn’t mean he’s a good storyteller however. He’s OK, but he throws so many literary red herrings into the stories without even realizing it, I suspect. So, where as he can draw, I applaud him, I pat him on the back — but now go and learn the other half of the craft, which is telling the story. I really think the storytelling and the characterization is the thing that has really gone south [mimics an old guy] with modern comics, I don’t bleedin’ know!

GROTH: [Laughs.] OK, C. C. [Beck].

WINDSOR-SMITH: [Laughs.] Yeah. It is characterization that I think has gone right out the bloody window. We can’t just pin it down to lousy drawing — however, if you can’t draw well, how can you create a good character on the page, how can you create a believable character from one panel to the next? So you can blame poor drawing to some extent. But if you can’t write well, how can you create a believable character with your words on the page? So we can also blame disinterest in writing. But really it’s the two combined, and even more so. Making comics today, it seems to me, isn’t about creating; characters or about involving the reader in a personality, and what that personality or groups of personalities are doing and how they feel about what they’re doing and what other people think about them. Instead, it’s about how cool the inanely overworked pin-up shot is. How many bleedin’ details can you stick up in the top left-hand corner before a caption goes over it. That to me seems like the very essence of what it’s about in commercial superhero comics. I would really like to read something that is - going to engage me, you know? But that’s not the criteria from Image and Marvel.

When I was doing that Wildstorm Rising thing about a year and a half ago — my one and only foray into Image — I... Well, for a start, I should never have bloody done it, and I wish I hadn’t. But I was talked into it and got kind of caught up in it, and it had to do with — oh man, it’s almost like a nightmare, only far remembered at this point — I was going through this hapless story where I couldn’t understand what anybody’s motives were. I was looking for motive. It wouldn’t come to me, I tried to read some of the preceding books and I still couldn’t find anybody’s particular characteristics — except for one guy was really big, or something like that. And then I had to draw these characters, these supposed characters.

GROTH: I assume you didn’t write this.

WINDSOR-SMITH: No, no. I mucked with the plot awfully, and the writer probably loathed me for it because I mucked around with the plot.

GROTH: [Chuckles.] He probably didn’t even notice.

WINDSOR-SMITH: No, no, he noticed. He was kind of miffed, so I heard from a third party. But I thought, “I’m just trying to improve the bleedin’ product, for crying out loud.” [Groth laughs.] But anyway, I did a real false start on it. I got three pages into it or something, trying every trick in the book to psyche myself into doing something like this. And it just wasn’t working. I was in a great depression over the story and I thought, “Oh God, this is the first time in my life I’m going to make an utter failure out of something.” After intense thinking, I realized what I was doing wrong: I was looking for characters! I know this sounds really glib as if I’m trying to build up to a funny line. But I’m really not. That was my problem: I was looking for characterization, and there was none. “There is no characterization! That’s what you’re doing wrong here, Barry!” They’re all ciphers!

GROTH: And you’re talking about characterization on the level of ’60s Marvel, right?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, absolutely. We’re talking minimalism here: but at least something that we know as part of the comic book process. I mean, I wasn’t looking for Harold Pinter here. [Groth laughs.] Maybe a little bit of diluted Stan Lee. But when I realized there was nothing to look for, that’s when I thought, “OK, all right, now it makes sense!” So then I proceeded to draw the damn story.

GROTH: How did you ever get sucked into something like that?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, you don’t want to know. Harris [Miller] talked me into it, you know?

GROTH: [Laughs.] OK. He is evil.

WINDSOR-SMITH: He really is. I mean, I love the guy and all that, but he gets me into trouble sometimes. He said, “This could be great for your career, Barry.” Yeah, right.

GROTH: Gil [Kane] tells me the same thing. He’s always calling him up saying, “You should do this new Image comic.” [Laughter.] Harris is always looking out for your careers.

WINDSOR-SMITH: That’s his job, he often reminds me. But yeah, I really think it is characterization that has sadly departed, whatever there was of it in comics gone by. For whatever we want to say about Stan Lee he did that thing with Spider-Man, where he actually had a point of view of the world and all that sort of stuff. So we can give him a short applause for that. And there really isn’t much of that any more.

GROTH: I don’t read mainstream comics much but we get piles of them in the office and I look at them once in a while. And because I read them as a kid and I can go back to that Kirby and Ditko and Stan Lee stuff and so on, I have this morbid curiosity about why they look like such unadulterated shit these days. I read interviews with contemporary creators who write and draw them and they seem to be very excited about what they’re doing. And I wonder about why the stuff is so wretched. I wonder if it’s just the Zeitgeist or if it’s just the creators themselves or if it’s me.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I know exactly what you’re saying. I have the very same wonders myself. You and I can just sit around and scratch our heads over the phone, because I don’t have any answer either. Yeah: is it the Zeitgeist? Are we missing something? Is it the same now as it was then but we just didn’t know because we were in a different position then? This sort of questioning comes to us all. It has been the standard cliché for decades now, from the ’60s with rock ’n’ roll, or at least the British invasion style rock ’n’ roll, where people would say, ‘They can’t play, they’re only playing banjo chords. Whatever happened to Ella Fitzgerald and Satchmo and hey, Frank Sinatra — now there’s a voice!” And all this sort of shit that I went through when I was a teenager, absolutely adoring everything I was hearing, from the Beatles to the Stones... Well, actually I was extremely judgmental even then: I fuckin’ hated the Dave Clark Five because I could see them for the no-talent copyists that they were! But I loved anything that I thought was quality, and I certainly thought Lennon and McCartney were.

I actually have this strong memory of an uncle of mine whom I greatly admired. He was a musician, played jazz. I was over at his house one day, I was only about 15 or 16, the Beatles had been around for about a year or so — at least in Britain; they hadn’t hit America yet — and he was sitting there just trashing them. Saying, “They can’t play any notes. You call that singing?” And I really disliked my uncle from that moment onward. I’ve never liked him since. Because he seemed to totally sell out himself as a musician. In other words, he wasn’t broad-minded enough to see that there is always new music. And he insulted one of my favorite things. So I’m dreadfully afraid that I’m doing exactly the same thing now!

GROTH: [Laughs.] You’re turning into your uncle.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, I’m turning into an old complaining fart. There are so many people, I hear it all the time: “Oh my God, I’m beginning to sound like my dad!” It’s a standard routine for stand-up comedians nowadays.

GROTH: But seriously, there is a maturing process, and some people go through it and some people don’t. And I think in some ways you do start sounding if not like your dad, at least like people you remember as having antiquated attitudes.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Somebody you don’t like. I can remember a long time ago, you did a major interview with Jim Steranko.

GROTH: Whew—you’re talking 25 years ago.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah. And you seemed absolutely in awe of Jim at the time.

GROTH: I was.

WINDSOR-SMITH: And you were young. And Jim was lapping it up because we know what an egoist he is. But in recent times, or at least within the last eight or five years, I can remember when you totally trashed him in print for some reason. It wasn’t out of hand, there was some purpose behind it; I forget what it was. I was thinking, “Gee, what happened to Gary in the meantime?” Yeah, we’ve all changed our taste — I guess. And now, Steranko was pretty damn good at what he did. We know it was derivative to a degree, but some of it wasn’t. So for the people who were working at that time in that heyday of Marvel comics, Steranko certainly gave far more energy to his books than your average guy. Certainly he was no genius on the level of Jack Kirby, but who the hell was? So Jim’s material was innovative to a degree, exciting to a degree, good for what it was. So why do you not see Jim’s work in that perspective? Or do you?

GROTH: Looking at his Marvel work, I can’t help but see it as thin and anemic. Whereas Kirby was genuinely original, and Ditko was too, Steranko was a compendium of graphic tricks and gimmicks picked up from various sources inside and outside of comics. So I don’t think he’s... If you look at it closely it tends to fall apart. It doesn’t hold up to very close scrutiny.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I agree with you. I was thinking that way back when.

GROTH: Yeah. Well you were probably ahead of me because as you say, I was in —

WINDSOR-SMITH: I was right in the thick of it and I was functioning in the same capacity as a storyteller. So I could certainly see through Steranko.

GROTH: Right. And l was just at the right stage to be in awe of that mystique that he carries around with him like baggage. But since then I managed to educate myself. Also I lived with him for about three months when I worked for him, and I guess I learned a lot more about him than I wanted to.

WINDSOR-SMITH: That sort of thing’s happened to me too, that which you thought once was so cool or whatever, and after a mental re-tooling due to any number of insights you realize that which once delighted you is just some sort of pap and you simply can’t understand what it was you were into at the time. And this is almost like a circular action. It comes back to your question about what’s happening to comics today.

GROTH: Exactly.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It doesn’t hold up; after you’ve gained through experience, through school, through self-teaching and analysis, what stays solidly honest to you? Even though I’ve traveled so many paths since 1968 when I first drew X-Men #53, right after Steranko’s short run as it happens, so many things have happened to me — obviously personal things happen if you stay alive long enough, but I’m talking about my perceptions of art, my needs, the things that gratify me, in fact even what art is. I’ve siphoned it through myself and I think I’ve come out a better person and an artist who is capable of realization in word and picture. Of all the perspective I presume that I have today I can’t seem to deploy it to read those old comics from the ’60s any more, I can’t read Stan Lee’s writing, it’s like getting hot pokers in the eye trying to read those balloons — see, that to me is still a bafflement. How could I ... So many things come into my head when I think of stuff like this. But Stan Lee’s writing, which used to flow through me and I thought was exciting, invigorating, stylish, any number of things... But today I cannot read a single balloon of it. And yet, the staging, the drawing, the drama, the natural intellect of Jack Kirby really hasn’t diminished, in my perception. And in fact I sometimes enjoy it all the more! Even though these are impossible heroes in blue tights. You look past that nonsense as you do when you look at a Picasso. We know people don’t have three eyes all on the left side of their head. There’s a reason that Picasso is doing this. There’s a reason for the extraction and the abstraction and the process of thought. Kirby still holds up! That fucking wonderful guy still holds up.

GROTH: Your bringing up Steranko made me think of something vis-a-vis Kirby. People like you and I can see the virtues of Kirby I think whereas a lot of people can’t. If you only look at the surface, I suppose it’s obvious why his virtues are difficult to see, because there’s something so adolescent about it. But it seems to me that as soon as you get into a kind of attenuated Kirby, like Steranko, Buscema and others the displaced virtues of Kirby just crumble. It has to be real Kirby or nothing.

GROTH: Your bringing up Steranko made me think of something vis-a-vis Kirby. People like you and I can see the virtues of Kirby I think whereas a lot of people can’t. If you only look at the surface, I suppose it’s obvious why his virtues are difficult to see, because there’s something so adolescent about it. But it seems to me that as soon as you get into a kind of attenuated Kirby, like Steranko, Buscema and others the displaced virtues of Kirby just crumble. It has to be real Kirby or nothing.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yes, I agree. Perhaps if Steranko had continued to create comics instead of becoming a soft-porn distributor, perhaps he’d’ve pulled away from the early influences and become a great in the field for real instead of just in his own head. But at least Jim offered something to us in the’60s, whereas Buscema’s applications of Kirbyism was utterly vapid and empty.

GROTH: Well if Steranko’s work displayed more ingenuity than Buscema’s even then, but the way I see it is, everything we find admirable about Steranko’s work came from outside Steranko whereas everything we love about Kirby came from inside Kirby, and that’s a significant difference.

WINDSOR-SMITH: True. I’m walking a bit of a thin line here because one of my new titles for Storyteller is a direct homage to Kirby, you can tell by the title Young Gods if nothing else. I’m not drawing like Kirby, you know — the way I did in the ’60s — but my pacing and acting technique is derived from Jack. I started Young Gods about two years ago from an entirely different storytelling point of view but after I completed nearly two stories I realized that the only way I wanted to do the material was as a tribute to Jack Kirby, the characterization is not Kirby — the characters are very much my own types — but the pacing, the panel layouts, and the backgrounds are very much synthesized from Jack. I think I’m doing him justice with this because I believe I understand Jack Kirby’s work deeply. Each episode is dedicated to his memory.

GROTH: That’s an important point, though: you’re not using Kirby as a source of content so much as the scaffolding for your own content. Earlier we were asking ourselves how to account for this miserable state of affairs in mainstream comics, and quite possibly it’s because comics are being written and drawn by people who haven’t learned to distinguish between using an artist as inspiration and using him as the single source of your expression.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Most of ’em are perhaps too young to have learned the process of discriminating the valuable from the crap. You and I after all are talking from some perspective of the years under our belts, as it were. Within my parameters, my overview, say, when I was in my mid-20s, I honestly believed the comic books I was creating had value to them … not all of ’em mind you, Avengers #100 didn’t really rise above street level, y’know, but I had pride in something about those books like Conan, Doc Strange, and stuff I forget now. My drawing wasn’t always the greatest but I believe my storytelling had integrity because I had a background in books and plays and other literary endeavors that wasn’t just comic-books: Hell, I read Steinbeck when I was 14.1 don’t see intensity in modern Marvel and Image and what have you, no matter how abstracted it might be for the sake of the superhero genre, I can’t see it.

But when I read the entirety of Alan Moore’s Miracleman I was thrilled by his diverse experience and knowledge — you don’t find that depth in Youngblood.

GROTH: [Laughs.] But I wonder if maybe they just didn’t grow up reading comics … Good God, I guess it’s possible they grew up reading comics in the ’80s, isn’t it?

WINDSOR-SMITH: It is, and I know nothing about comics from the ’80s. Weren’t comics in the ’80s dominated by the John Buscema clones, art-wise I mean?

GROTH: I’m not sure, but I think it was just real garbage.

WINDSOR-SMITH: You really don’t see any evidence of John Buscema cloning in them any more. Now, John, who was a very good draughtsman, was the most feted penciler that comics had seen at that time. But for a man to have that kind of talent, that capacity to draw, or to cartoon, and yet have no intellectual basis and seemingly put nothing into those stories that you can come away with smiling … That to me was always the most bizarre anomaly, you know? He was a naturally talented man. I always compared him to Paul McCartney where Paul McCartney was obviously the best musician in the Beatles, there was nothing he couldn’t do, you know? He could play most all instruments, had a fantastic voice as regards quality and range, he was a terrific writer … He was all-round top-notch. And yet Paul McCartney’s work is vapid. He wrote some really terrific tunes every now and then I have to admit, like “Hey Jude,” I mean, God was sitting on his shoulder when he wrote “Hey Jude.” But in general, Paul McCartney gives you nothing…

GROTH. Just fluff.

WINDSOR-SMITH: He’s like the sweet tooth of music. And yet his partner, John Lennon, who could not play as well, could not sing as well, wrote some very good songs but really wasn’t as prolific as McCartney. But John [Lennon], just like Kirby, still stands up. Because there is an almost inexplicable value to what he was doing. I say “inexplicable,” but you could always try to point out what it all was, but to a degree it is inexplicable. If you’re touched with something, a vision, a hard-edge vision perhaps, even a soft vision, as long as you’ve got vision! As long as you’ve got vision and you can send it out, you can project it ... That’s what Kirby could do with aplomb, it’s what John Lennon did, it’s what a lot of people did, I’m just using two popular icons right now.

So in the case of John Buscema, he could certainly draw the human figure finer than Jack Kirby but there was just no valid intensity to what he was doing. It was just pap. And now, just recently I heard that Buscema has retired. It took me a few seconds to understand that ... How does an “artist” retire? One turns sixty-five years of age and one says to the wife ‘Well, dear, time to hang up the ol’ pencil sharpener. My time is done.” How can a real artist retire from being an artist? I understand John Romita retiring because he was the art director at Marvel: It’s a job you do and you get to a certain age and you leave that job and go fishing or something. But Buscema is an alleged artist and you can’t retire from art. So maybe John is retiring from drawing comics, is that it? Then, if that’s the case, John’s comics weren’t art. Is John now going to pursue “real art” in his latter life? Does John confuse painting at an easel with brushes and oils with the act of creating art? Buscema has been turning out comic books for 30 or more years ... Why didn’t he make them art? Look at his work, even the Silver Surfer books that were among his most facile and pretty, and you won’t find art; you’ll find a journeyman talent wasted on a field that prefers his kind to my kind.

GROTH: I actually attended a chalk talk that Buscema gave the Marvel staff in the ’80s. It must have been around ’82 or ’83.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It was at Marvel?

GROTH: At Marvel’s offices in New York and the room was full of inkers and pencilers...

WINDSOR-SMITH: What the heck were you doing there?

GROTH: I’m not sure how I got in there. Well, first of all it was obviously before Marvel barred me from the offices [BWS laughs], but somehow I wheedled my way in and I taped it.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Is that so?

GROTH: And it was the most appalling thing I had ever seen. It could have been subtitled, “How to Become a Hack.’’ He was giving lessons on how to take shortcuts and how to do work quickly.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh fuck, really?

GROTH: And the most appalling thing about it was that it was done in all sincerity. He really thought he was teaching these people valuable job skills.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Sort of like the live version of How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way.

GROTH: Yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Which is a book that should be burned. [Groth laughs.] I would never, ever agree to burning books, you know? But by fucking hell, if there’s ever a book that deserves it, it’s How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way.

GROTH: Exactly.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I only saw it by browsing through bookstores at the time. But we now have it in the studio as an icon. [Laughs.] So I had a chance to sit down and look at it properly one day. I was fuming! Absolutely fuming.

GROTH: I think we’ve probably said this before, but it’s tragic that someone with so much craft skill can apply it to something so vacuous.

WINDSOR-SMITH: You just said the word: he has so much craft. If ever anybody was confused — and I know a lot of people are — about the difference between art and craft, and that they do not go together like strawberries and cream, if anybody can really grasp what we’re saying here, that is, the difference between Kirby and Buscema, there’s your bloody fat dividing line. I mean, it’s a seven-lane highway, right between the two! The difference between art and craft. We said it here first.

GROTH: One thing that occurs to me is that what is explicable about art is the craft and what is inexplicable about art is that mysterious dimension that you cant put your finger on.

WINDSOR-SMITH: The spirit of it.

GROTH: Yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I never saw Jimi Hendrix play, I never saw Jack Kirby draw, and these are two great losses — but I would have loved to have been near Jack Kirby physically. Not if he was doing a convention drawing, as in “Oh Jack, do me a drawing!,” but at the real times when he was really creating I’d love to have been present when he invented the Silver Surfer and when he created Galactus. He’s saying, “OK, I’m going to have this big guy who goes around eating planets.”

GROTH: Yeah, just watch him compose pages.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, and feel... I’d literally be a fly on the wall because I know he was supposed to be a very outgoing man, but I doubt very much that when he was on that level of creativity, that people were around him, or could watch him. It had to happen in private. It’s too fucking energetic. It’s too... It’s close to genius is what it is. Inside our field, it’s as close as we’re going to get for a bloody long time it seems. And I would love to have just been able to suck in, feel the energy, the spirit coming out of him. God, talk about being bathed by God’s light or something. This is back to what you were saying about the palpable and the non-palpable when it comes to art — I as a person wouldn’t have been able to understand and translate his power, because it’s entirely his own meta-energy. But it’s like you don’t have to understand what the sun is and how it works in order to get suntanned. I would have liked to have gotten a slight brush, metaphorically, of the heat that must have come out of Jack Kirby when his mind was really, really roaring. And to think he could translate it onto paper, with a stubby bleedin’ pencil to me is just one of the all-time gases of this world. And we are very lucky that we were around and at an impressionable age when that stuff was coming out.