THANK GOD FOR COFFEE

GROTH: Speaking of craft, I just read the third and fourth issues of Storyteller and one thing I luxuriated in was the immaculate craft.

WINDSOR-SMITH: You think so?

GROTH: Yeah, and I’m referring not just to the drawing but the storytelling, — the writing, the timing, the pacing...

WINDSOR-SMITH: Thanks.

GROTH: It all comes together beautifully.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Thank you very much, Gary.

GROTH: I know where you got the drawing from: you studied academically and of course Kirby was a big influence. But the first writing that I’m aware of that you did was Archer and Armstrong, I think.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I wrote Weapon X before that.

GROTH: Oh yes, and you might have written some stories for Epic.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah.

GROTH: But nothing as complicated and as slick as Storyteller. I’m wondering where you learned the craft of writing — who your influences were, and how you actually sat down and learned it.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It wasn’t Stan Lee. [Groth laughs] I always should have been writing my own books. I didn’t get sucked into Marvel comics in too many ways. I didn’t fall for the hype... I mean, I did for a while, but after a couple of years I was out of there. I didn’t become a hack, thank God. One of the things I did fall for with Marvel Comics — and this is even before I joined the company, as a reader of them back in London —was the team effort. Stan and Jack. Roy and John. I accepted that as pretty much the rule of things.

GROTH: Collaboration.

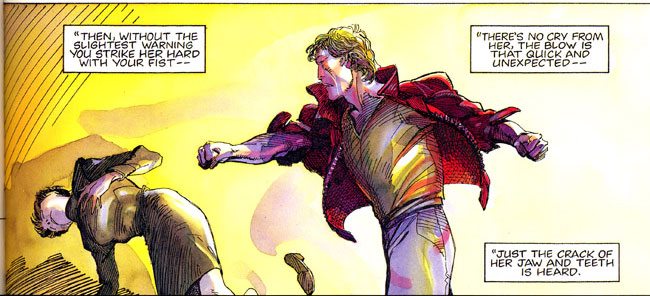

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, that’s how it worked. And I’ve always regretted my going along with that. Over the years with all these bleeding comics I’ve drawn, usually I was the storyteller, I was the director of the story. I don’t think there has ever been a case where I worked from somebody’s story where I didn’t change it in some fashion or another. This made some friends for me, and it made some enemies. I know Chris Claremont was always pissed when I would change his bloody stories. And I would write dialogue on the sides of the pages, often quite a lot of which got swiped by the scripter and he took the credit and the money was his. But I always just took a back seat in that regard, although I never really verbalized it that way to myself. I was always so bloody disappointed when things didn’t go … I would look at my pacing and my characterization, like body language or a certain turn of the head or raise of the eyebrow, which was always fairly subtle compared to something like Jack. And then I would read the words that had been written to it, and I said, “Fuck, that doesn’t say what my figure was implying!” The only other time it really worked was when the supposed writer, the scripter, would follow what I wrote in the margins. Then we would find this balance of acting and script, stage direction and everything. I’m not saying that was always the case, Gary, but it was enough of the case for it to really stick in my craw over the years. So I started scripting my own stuff around the late ‘80s, I did a couple of short stories, I did a funny story with Ben Grimm, an April Fool’s joke story which everybody still seems to covet in some way. That was the first comedic story I ever did. And I worked on that thing the way I’ve always worked on stuff: I never told anybody what I was doing. I never asked for permission from an editor, like, “Do you mind if I do this?” I’d just go ahead and do it. If they didn’t like it, then, “Fuck it. You don’t get it then.” Luckily this thing was a major Marvel character, and it was funny. What it was as a matter of fact was a tip of the hat to the old Kirby-Lee things where Kirby and Lee would do funny adventures of Johnny Storm and Ben Grimm. It was kind of like that. And I still like it today. The drawings are a little bit queer, but … It works. And I felt satisfied.

Many of my stories that I wrote and drew have never been published. Certainly during the '80s when I was hardly being published at all, I was turning out tons of bloody material, which I was writing and drawing. I’ve really learned the craft, the kind of storytelling craft that you see now in Storyteller from all that work that’s never been seen by the public. I allowed myself to fail miserably and to triumph with something all on the same page.

I learned, for instance, a very simple process that works perfectly for me, which is: Don’t draw. Write only. It is the words that are important. And it is. Frankly, in Storyteller, to be perfectly honest with you, the quality of my drawing has gone down a bit from the immaculately inked works of the ‘80s because I am turning out 32 pages a month here. Along with running a studio, I am drawing, inking, writing, coloring, and making all the business decisions that I can, etc., etc., all in 30 days! I mean, where the fuck do I get the energy for God sakes? Thank God someone invented coffee.

GROTH: [laughs] Are you actually doing 32 pages a month?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah.

GROTH: [Long pause.] Jesus.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It’s big stuff. The first book is 42 pages. But yeah, it’s 32 pages from there on. There are no ads in this book. It’s full right from the start to when you fall off the last page. It’s all story.

GROTH; I’m worried you're going to have a heart attack any day now.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah... Don’t say it! [Groth laughs.] It’s close to the truth. No, no, I’m in seemingly pretty good health, considering I never sleep. But the unpublished '80s is when I learned to put together all the bits of craft that I’d learned in the '70s and the '60s. I learned to draw better simply because I was under no pressure from anybody. I mean, I went broke doing this, you have to understand. I was very poor in the ‘80s. I did quite a stack of covers for Marvel, none of which I signed, mostly for the New Mutants book and I also produced the occasional comic that got published, but the crappy money from those X-Mens and stuff paid the rent and not much else. But what I was doing behind the scenes was writing. Learning to write my way. I’ve never written a play, but I shouldn’t be surprised if I’m capable of it because I’ve read enough plays that I understand the process and have a deep love for theater. I wrote a screenplay during the late '80s, it was never bought but it was an invigorating experience that I’m still quite proud of. In comics you have to think visually as you write, you have to think stage presence, and you have to think left and right camera work. These are part of the rules in theater and film. And yet, it’s very rare, if not perhaps unknown, that I can read a comic book, including my own that’ve been scripted by others, where I felt that there was an utter complete unison between image and word. The balance I’ve always dreamed of having is where you can make it flow so easily — and this really to me is the Grail for me — where I can make my reader forget they’re reading a comic book. That’s what I aim for all the time … y’know, like in the movies — if you notice the architecture of the theater during the film then the story didn’t take you away. If I do something too flash with my visuals, I will chuck it out and do something less flash, because I don’t want anybody to say, ‘Wow, look at that cool drawing, man!” I want it all to balance. There’s a word I’m looking for, I can’t bleedin’ think of it. It’s some word about perfect balance.

GROTH: Unity or harmony?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Harmony, yeah. Some Zen harmony thing. [Alex Bialy yells to Barry from another office.] What? “Synergy,” right, thanks! ...What? “Synchronicity.” Another bloody good word. I know it seems like I was a penciler and inker and colorist for the longest time, and suddenly I’m a writer, too. But the fact is, I took a whole decade off to learn how to balance the craft of storytelling. Because I just fucking hated that I could do such nifty drawings of characters who you really couldn’t believe in, because they’ve got all these ridiculous costumes on, and yet I could draw them so well, that you really had a sense that they could actually be flying or whatever. And then the bleeding words would be attached to it, and the whole thing would go out the window into the comics-language ghetto of impossibly long speech balloons where the character exposits on something that should’ve been plain as day by the visuals and where nobody stops to breathe in-between sentences or ever goofs up their words: In one of my first stories (that Ben Grimm thing I mentioned) Ben is so flabbergasted by a trick Johnny Storm played on him that Ben speaks (yells actually) a spoonerism. My editor on that job called me up and asked if I meant to do that! Can you imagine?! How on earth can one write a spoonerism unwittingly? A spoonerism is an oral gaff! Of course I meant it!

GROTH: It seems to me that one of the essential requirements of a good comic is the seamlessness of the writing and drawing, where the writing and drawing in fact become a single component, if you know what I mean.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, I think that’s the ultimate goal. I can draw as flashy as anybody. I can draw 10,000 little gadgets and lots of big guns and all this sort of shit just to say, “Look at my pictures!” Again, going back to the old whipping post of Image Comics, and their doing the group thing, the team thing, it seems to me like they’re all onstage — I know I keep mixing music with art and comics and all that, but it’s a continuing metaphor for me — that they are a group, like a rock band, onstage, and they’re all trying to be louder than everybody else. [Groth laughs.] Jim [Lee] goes up to nine, so Cherris goes up to 11. “Please notice me —I am louder! I can play faster!” “Listen to that guy, he’s actually shouting rather than singing!,” because he wants to be heard over the guitars which are all now being played at 11. That is not a concert. That’s the perfect word: “concert.” Nobody is in concert.

GROTH: That’s a perfect analogy.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah.

I want my characters to be alive to the audience, I want them to care about the people I draw. If one of the characters does something stupid, inane, or wonderful, I want them to feel stupid with the character, I want them to feel wonderful with the character. This to me, is the essence of storytelling. It’s Charles Dickens. He was just words on a page, sometimes his stuff was illustrated, but sometimes I think actually the illustrations were an intrusion, because the illustrator of a Dickens story wasn’t quite good enough. We’ve seen plenty of popular authors who’ve been illustrated — everybody, from Burroughs or whatever, to John Tenniel doing Alice In Wonderland. I never liked Tenniel’s drawings for Alice. She never looked like the Alice I imagined. So I found Tenniel’s illustrations an intrusion. When Rackam illustrated it, I thought, “Yeah, that feels nice.”

But I’ve always felt that illustrations in a prose story get in the way somehow. I’ve never seen the perfect balance. Maybe there is, I just haven’t seen it. But with comic books, we are obliged to find the perfect balance, because that’s what we’re doing! That is the very essence of what we’re doing. And if I may be so bold, I think that one of the many, bleedin’ reasons why we as an artform haven’t been recognized in America as something valid, is because of that lack of symbiotic balance. How can an ordinary person, a civilian out there, pick up a copy of fucking WildCATS or something like that, and say, “Oh yeah, this is engaging to my sensibilities as a human being?” Because the very essence of the thing implies that you’ve got to read it, it’s got word balloons on it after all, but who in the adult world wants to get tied into the doings of a bunch of vacuous superheroes firing giant guns at each other? Comics can be stories about real people no matter what colors they wear if only the essence of real people are injected into the stories. All I see of late is pageants of outrageous color and costume draped all over the place to thinly disguise the lack of depth or anything remotely similar to drama. There’s got to be a balance somewhere. And it’s very rare that I’ve seen that balance in comic books. At least on any sort of sophisticated level. And that’s why my book is called Storyteller. It’s not called Barry Windsor-Smith Illustrator or Bingbangboom. It’s Storyteller.

I like to believe that it’s those creators who can write and draw with equal passion that will give this field the recognition it needs; it’s those people whose intent it is to tell a story and not just make pictures. Frank Miller is an excellent example of this. I wish Neil Gaiman could draw! Mike Mignola is now the sole author of his work with Hellboy, David Lapham. Rude and Baron are an example of almost perfect teamwork, however — they must sit on the same stool at the same desk as they’re putting Nexus together.

HUMOR AND DEPTH

GROTH: One thought that crossed my mind when I was reading Storyteller is that it seems to me that the best artists in the history of comics either had the capacity for humor, or that their work was dominated by humor. I’m thinking early on of Kurtzman and Eisner.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh right, of course.

GROTH: And then Barks would qualify. Jack Cole.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh yeah.

GROTH: And of course later on in the alternative and underground field, people like Crumb and Shelton.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right. I think you’ve got a fairly good pattern going there.

GROTH: And I wonder why that is. To get back to our whipping post, one of the characteristics of Image Comics is their humorlessness.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Absolutely. Not only is it humorless, but it’s so arid, it goes beyond that. It emanates from the printed page just how seriously they take themselves. Which is so bloody ironic.

GROTH: So earnest.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yes, earnest. I don’t know if I could ever apply that word to our whipping post.

GROTH: And someone like Kurtzman was a great humorist, and he also did moving, serious stories in the war books.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Absolutely. If Kurtzman was only a comedian, let’s say, there would be no depth to him. Some of the best — oh shit, I’m going to quote myself from one of my stories, which I hate doing — the best, the funniest people, are the people with a hard edge. If you’re Soupy Sales, I mean frankly, I’ve never thought of Soupy Sales as funny. Admittedly I wasn’t around as a child when he was doing that stuff, and I know he really did do it for children, but he still does comedy for adults, and I never saw anything funny about it. But when someone like... Oh shit, I can’t even think of one bleedin’ comedian right now… [Alex yells to Barry again.] What was that? Dennis fucking Miller. You like Dennis Miller?

GROTH: Yeah, yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Hot shit, you know? He’s as funny as all fucking get-out. I very rarely laugh out loud, at anything for that matter, and I don’t laugh out loud at Dennis Miller. For one thing, he talks too fast and if you laugh you miss something. But the stuff is so fucking hard-edged. It’s bitter, it’s angry, it’s perceptive, it’s everything that bleedin’ Soupy Sales ain’t. I think Miller really stands out above the crowd — he’s got his own crowd, and he’s even higher than that. I think that if Kurtzman was a Soupy Sales, if he was a comic, comic artist, a funny guy, then he wouldn’t be very funny. And if he was only a serious bloke and he only did war stuff, only did the nit grit, then it wouldn’t be that memorable. It isn’t just two sides to the story. It’s multi-faceted — and I know that’s walking into cliché. But it’s like if you meet somebody on the street, or if you meet somebody at a cocktail party: are they funny? That’s good, that’s entertaining. Have they got something sad to tell you? Or are they funny once they have a sad look in their eyes? That’s always the best thing. But if he’s sitting there being funny and he’s got a down’s nose on, it’s not so damn funny any more, you know?

GROTH: Which brings us to the fact that there is an unde lying seriousness to your work in Storyteller.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh yeah, sure.

GROTH: And I just started to realize that with the third and fourth issues. It is starting to coalesce.

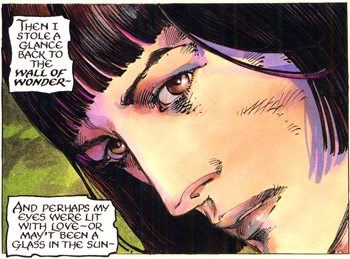

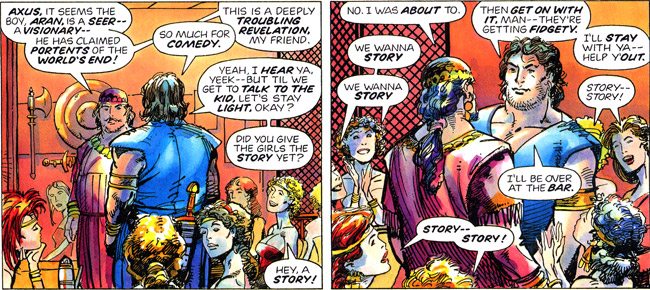

WINDSOR-SMITH: This is not intended as a comedy... It’s not slapstick by any means. Everything has ... Well there’s The Paradoxman, which is grotesquely serious. I’m only just beginning to get some minor humor into that one with the fifth story. But the other two, yes of course, the characters don’t take themselves too seriously, thank God, and they do do quite ridiculous things. But again, it’s looking for that Zen balance. I don’t know if you got the story where I reveal that Axus The Great [from The Freebooters] is going through a mid-life crisis. It’s the one where Strongbow, the young strapping guy comes into town.

GROTH: Sure, I remember it.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It’s Axus’ pet peeve. Not necessarily Strongbow, but all of these youngsters who’ve come up behind him since he retired from being a roustabout. And they’re all making more bleeding money than he is, and they’re all still handsome and have got 22-inch waists. There’s not a little bit of biography in this.

GROTH: [Laughs.] I was gonna say.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, sure! It’s also true of so many other things I’m doing. The Aran character from the same title, is me also, when I was younger. The stuffiness of Heros of Young Gods, where he’s slightly aloof to keep up an image bestowed upon him by others, that’s also me. It’s all biographical. Even the women — I have a very strong female side, as a person. I like to make people laugh, but I’m also a very serious sort of person. So that’s how come these characters come alive, because I’m tapping into my own experiences and my own energies.

GROTH: There were two panels in the fourth issue of the “Freebooters” storyline that I thought was strikingly auto-biographical, and that’s when an apparition appears before the young guy, and he says, “I understand you fully. I once was like you — so impassioned about so many articles of life.” [BWS is laughing.] And then he says, “But needless to say, that was before I discovered villainy. In these later years I realized that idealism and all its feckless trappings is but a path to delusionment and misery.” [BWS laughs.] And I thought, “Hey, that’s Barry!”

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, on the money.

GROTH: In fact it’s both sides of you.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I was speaking from experience. But you must understand that I spoke like that once upon a time: I no longer feel that I have lost myself. In case you didn’t get it, and I certainly wasn’t going to put it in explanatory captions, that guy, Uta Prime, is a split personality in the most literal sense. Which is why you find him arguing with himself suddenly. It’s going to come out much later. One of my pet-peeves about comic books is, one should try to tell the story as best as one can, and thus, one will not need “Meanwhile, back at the ranch”-type captions. As far as I know I’ve never written an explanatory caption.

Uta Prime, he’s been around in my canon of material for about 15 years by the way. I did a story that was never finished and thus never published with this very guy. He didn’t have that name then, but he looked exactly the same, and it was a suicide story. It was an eight-page story of him literally just arguing with himself. He would stand with his body weight on his left leg, and he’d be saying something or other, and then he’d flip his body weight on his right leg and he would argue with himself. What it was was, there were two personalities inside one body; one was a good sorcerer, and one was a truly evil sorcerer. The good sorcerer was trying to argue his way out of not wanting to be in this body any more: “I don’t want to be a part of your evil villainy any more.” And then of course the nasty guy is just calling him names and all sorts of stupid stuff. And the good side realized, by something that the bad side said, the way out, the way to be free. And that was to kill himself. So even as the good side was ripping himself to pieces — it’s the most ghastly piece of suicide you’ve ever seen, literally ripping his ribs out— the bad side was saying, “Stop this! Stop this! What are you doing? Ow!” [Laughter.]

So that’s where the Prime guy comes from. I knew when I wrote that little chapter there that I was going to confuse the piss out of people! The guy seems to have a split personality, but I’m not explaining anything.

GROTH: And you shouldn’t.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I’m hoping people get the drift, but if they don’t, I’ll follow up with another story at some point where they will get the point. But yes, that whole thing about the articles of life... Yeah, that came right out. That kind of stuff just falls off the pen.

OPENING CHANNELS

GROTH: I think I read somewhere that you said you actually write the story first and then you draw it. You don’t write page by page as you go along.

WINDSOR-SMITH: True. But I re-write as I draw.

GROTH: Now, I assume you have all three stories running in those 12 issues plotted out.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It was a necessary item really because when I was showing the stuff around, I mean, it was a bizarre concept: a big, fat book... There were a lot of things that publishers — including Harris [Miller], I have to say — just didn’t understand what I was going on about. I’ve never had to do a major sell on anything. But I realized, “Well, crumbs, if it’s going to be that bizarre sounding to publishers, I guess I’m going to have to do a hard sell.” So I sat down — literally, I sort of chained myself down to do it — and wrote out the complete stories: The Paradoxman, The Freebooters and Gods, knowing full well that what I was suggesting to any given publisher wasn’t going to be what the fuck it was going to be. I was just making the shit up as I went along, just so it seemed as if I had it all wrapped up. But I knew very well that once these characters started to come alive, that they’re going to tell their own story and how on earth can you sell a story, a book or a movie by telling the Man “Hey, gimme some money — the story’ll work out in the end.” We’ve got a situation now where the Young Gods have been sitting on this bloody planetoid looking for dragons for three bleedin’ issues!

GROTH: How far ahead do you actually script a story?

WINDSOR-SMITH: You mean as I’m working?

GROTH: Yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I write it day to day. On a good day I can write four pages. But I genuinely mean this: I really don’t know what’s going to happen from one morning to the next. I honestly don’t.

GROTH: What I actually meant was how far ahead of the drawing do you write the story?

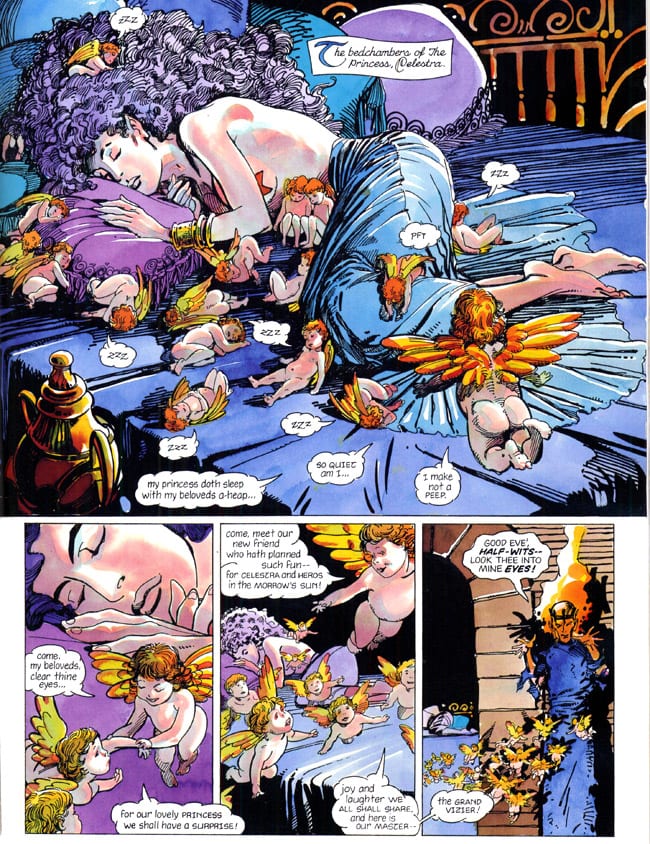

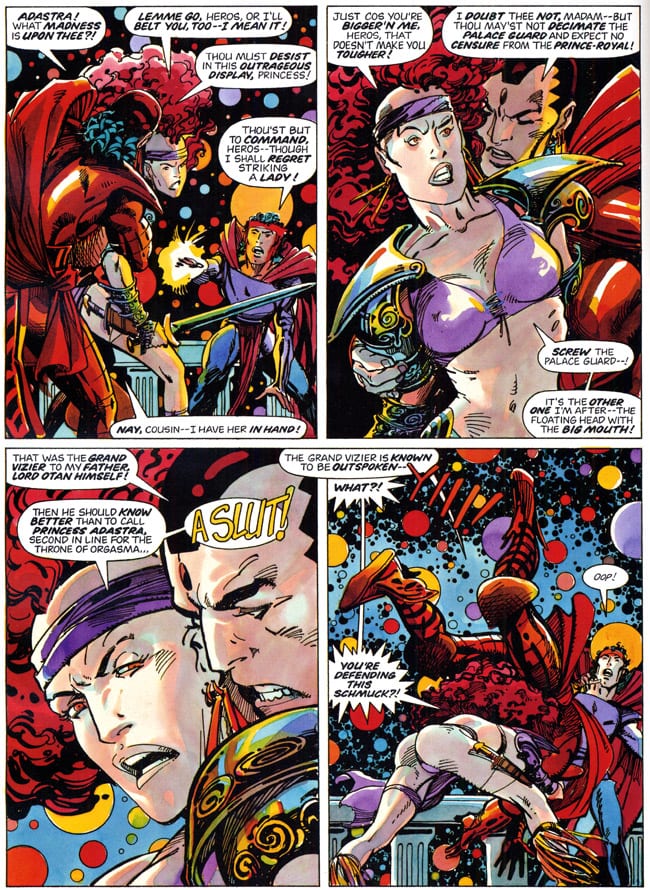

WINDSOR-SMITH: It just depends upon the flow. I know that if the characters are really on the ball — and I really do see them as separate creatures from myself— if they are really interacting with each other — I know you’ve heard this from other people, and I don’t know if it’s bull or not, but in my case it isn’t bull — I am hard-pressed to get everything on paper that they’re saying. I have to write so fast, I do all my scripts by hand. I’ve got computers and all sorts of bloody things but the essence of writing with a #2 yellow pencil on a yellow pad to me is so intimate. I can’t sit at my word processor and do it. I like to hear the scratch of the pencil on the paper. And sometimes I have to write so bloody fast just to keep up with what they’re all saying. Especially if they get into an argument or something where they’re all talking at once. I will go into certain shorthand which is personal to me, not proper shorthand. And if I’m open enough I’ll catch as much of it as I can and I’ll just keep going. If something slows down it might be a flaw in the character. It might be a red herring in the story. Or it might be any number of things. But as it slows down and I don’t have to write so fast, then I’ll grab a piece of pre-drawn up paper and start whacking in figures for their staging. This happens all day every day around here. Not to say there aren’t times when I draw a blank. I think when I go blank on these characters it’s because I have fallen into the trap of imagining that I know them well enough to think I can coast with them for a while. If I am missing something and I slow down, I think it’s me. I think I don’t have my channels open to them, you know? Because a certain number of these characters have become so strong, even just within five books, they really do dominate the stage a lot — especially like Adastra, the elder princess in “Gods,” she is such a strong personality.

In fact I’ll tell you this because, why not? She took over a story in Chapter 5 of Young Gods, I thought I had that pretty well worked out, it was one of the short chapters because it wasn’t the lead story for them, and it was about six pages, and she totally took over the fucking story and the staging and everything. I know it sounds like I’m loony toons here, Gary. Don’t think that I’m thinking, “This happens all the time to everybody!”

GROTH: No, no. I was going to ask you how spontaneous you can be as you write and draw these stories.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It’s how spontaneous they are, really. Again, I’m just here trying to catch as many of their words as possible. Anyway, she just bleedin’ walked in and took over the whole story. And the story did not go as I had planned. She really had a bee in her bonnet and started shouting at Strangehands, and I’m drawing this thing thinking, “Crumbs! This isn’t what I wanted to do! She’s really coming off like a bitch now! Shit, she is a bitch! She isn’t even being charming about it any more. She’s getting on Strangehand’s case because he’s smaller than she is.” So I had to stop the goddamn story. It was lettered and everything. And it took me days to figure out how I can let these characters take over the stage like that. I just slammed it down and for a couple of days I did something else, asking myself, “Should I really let this go? Aren’t my readers really going to dislike Adastra now because she was such a bloody bitch?” Sometimes it feel like I can’t control them. So I thought about the story for the longest time, and I started it all over again. But what I did was, I had an imaginary conversation in my mind, telling Adastra, “If you keep this up, I’m not going to give you your fan mail any more.” — like I’m a fuckin’ lunatic, right?

GROTH: [Laughs.] Right.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Arguing with my own characters. So what has happened now — and in fact I’m telling you, but nobody in this building knows about it yet; I guess Alex is going to overhear this, and my letterer is going to go fucking nuts when she finds out — we are actually going to publish the story of me walking into their stage to talk with Adastra about her overt personality [laughs wearily]. I don’t know how I’m going to fucking pull this off, I really don’t. But when I was trying to tell Adastra that she’s going way too far, she was fucking arguing with me too — and I’m the bloke who created her! God, anybody who reads this thing is going to think I’m out of my fucking mind. [Groth laughs.] [Note from BWS: as of August 15, Adastra and I worked it all out amicably as can be seen in Storyteller.]

But really, this is the act of creation. I mean, you’ve got to believe in these people. So she’s got this whole bleedin’ attitude towards me now. So I thought, ‘Well, this is what’s happening with the characters. If they can step outside of themselves, let’s see if I can pull it off, in print, without it seeming phony.” I mean, this is a real test. If it seems the least bit phony, or like one of those “Stan and Jack walk into the story” things, the “Aren’t we being cute?” thing, then it’s not going to work. So ... [laughs] I don’t know. Fuck. So we got two chapters here. They both start off with exactly the same themes. And yet one goes batting off in a different direction, when Adastra gets crazy; and the other one is now written and drawn, and I kept very tight control on it, and this was after I gave Adastra a bit of a dressing down. So now that I’ve gotten the one that I wanted out of the story, I’m going to go back and make the sixth chapter the one where Adastra charged on stage and started dissing poor old Strangehands. It’s a crazy loony toons sort of way to do things, Gary, but...

GROTH: But what you re describing seems to me to be a very important and vital part of the creative process, where the process itself creates new possibilities.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Hey. You just said it perfectly.

GROTH: That’s what I was curious about, because I assume you have some sort of an outline for the stories.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I’ve got an outline.

GROTH: And what I wanted to know was how much you deviate from that.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Continuously. I never really know. As I say, it’s up to the characters. From the very first moment that Strangehands said to Heros, “Let us go chase some dragons” — which is sort of like saying, “Let’s go to the gym.” Because the guys really uptight about getting married, he’s afraid of fatherhood, he’s still a virgin, as is his wife to be. And he’s freaking out on the evening of the wedding. So it’s sort of like saying, “Come on, let’s go toss some balls down at the gym,” and kind of get that male energy running. So he says, “Let’s go chase some dragons,” because they’re flicking gods after all. I thought they’d be chasing dragons by book #2. I’m not very good at drawing dragons — I don’t know why — but I was gathering reference for dragons. Who does the best dragons? I finally landed upon some fairy tale type dragons from Arthur Rackham, but I need them to be bigger and chunkier and more Kirby-esque, so I’ll make it a balance between the two. So, back in February, I’m preparing myself for book #2 because I’ve got to draw a bleedin’ dragon. Well here we are at book #5 in the middle of the summer, and we still haven’t seen any dragons! And this is why Adastra is so annoyed: she came along on this trip because Heros and Strangehands promised her dragons!

So really, it’s not as if I’ve got that much control. I will put my foot down when things go utterly wrong, but generally I’m letting these people tell their own story. Unless they get lazy. Then I’ll sort of prompt them a bit, like a stage director ... I can see it now: “Comics Journal interview with That Out Of His Fucking Mind Guy: Barry Windsor-Smith.” [Groth laughs.] You always imagined it over the years? Well guys, here’s the truth.

HOW HE GOT FROM THERE TO HERE

GROTH: You have a fascinating and anomalous career trajectory. You grew up in the assembly-line industrial system of mainstream comic, the tail end of it, before the enlightenment so to speak, before undergrounds really hit and established the concept of comic book artists exercising the rights of traditional authors, the concept of creators’ rights came to the fore, and so on. Then you self-published under the Gorblimey Press. So you’ve straddled both of those worlds. I’m interested in how you got out of the former. During the period you started Gorblimey Press, you and I weren’t talking much but I had the impression from my understanding of what you were doing and your public statements, that you really turned your back on comics and you were embracing what you felt was more serious art. And then you got back into comics by doing Machine Man, which sort of shocked me because I couldn’t reconcile that with my revised conception of you. And then you went on to do Weapon X, the Wolverine story, which I also thought was an artistic dead end for you. Now finally it seems to me that you’ve come out the other end — you’re doing the most personal work of your life. But it took you a while to get to that point.

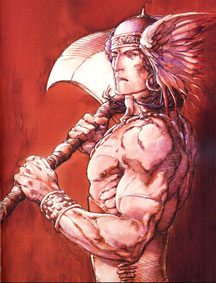

WINDSOR-SMITH: It really did. This might be a matter of naming the wrong party or something, but when I left Marvel, and essentially by that left comics, I wasn’t saying that comics stink; I was saying that the business stinks. I’ve always loved comic books and always will, obviously. But it was the business, it was the publishers that were so disgusting to me. And all of my idealism was crushed by those publishers. And I wouldn’t be surprised if they were pussycats compared to some of the people around now today. It was just the most unidealistic, non-romantic place to be, yet my entire outlook was through the eyes of a romantic artist. I was lucky to get Conan so I didn’t have to draw superheroes, with a guy who doesn’t wear a cape and spandex. I was able to put more humanism into those stories because he didn’t fly and he wasn’t omnipotent or fire bolts from his fingers. So that was good for me. In leaving the field, it was a wholly idealistic move toward my freedom. At Marvel I was restricted by editorial and commercially placed policies that I considered inane and hypocritical.

Here’s a little anecdote that might explain the absurdity of things I dealt with at Marvel — In one of my latter Conan books I devised a short sequence where, if I recall correctly, Conan is frustrated in his interest in a woman, and as a device to enhance his sense of frustration and annoyance I had a dog, a street mutt, following Conan and barking at him. Eventually Conan kicks the bloody thing and it runs off. I created that sequence directly from my own experience.

Roy Thomas called me when he received the pages and complained about the scene because, he said, Conan just wouldn’t do that. Conan wouldn’t kick a mutt that was pissing him off. It was OK for The World’s Most SAVAGE hero to hack men to meat but, in Roy’s overview, he’d never kick a dog out of sexual frustration!

The sequence stayed in but I hated being taken to task for being original and perceptive. I’m still the same way: I can’t stand anybody telling me what to do. I can’t stand anybody taking a moral stance against what I do, because I think of myself as very moral — even though I am the type who will bend any rule that has been made, sometimes just ‘cause I wanna, there’s no other reason.

When I was doing my own thing for 11 years even that had it’s negatives. I put out one picture I thought, upon reflection, so bad, and so lacking in everything that I had intended it to be (even though I have to say it was one of my more facile works, it wasn’t raw like a lot of the other stuff I did), that I would lose sleep questioning myself over and over how I came to the point that I couldn’t discern its faults. The problem was, it sold terrifically well. It sold just as well as the pictures I did that were truly heartfelt. Suddenly I was beginning to get confused about my muse. Even within the freedom of my own choice, I found that I was suddenly faced with another dilemma: I’d proved, unwittingly and without intention, that I can sell a lousy picture — or what I thought was a lousy picture. So then I thought, “Hey, this means I can publish all that shit that I didn’t want to publish before because I didn’t think it was good enough!” Because actually I painted far more pictures than I ever published because they didn’t rise to my critical standard, or whatever, so they would never be published. All these things started to happen, so the whole damned idealism started to unravel for me, you know? There’s this other bloody awful thing: I would sell the reproductions of my pictures as cheap as I could, and I genuinely mean this. We would make a profit but we didn’t get rich. And there were other people out there imitating me who were selling their stuff for more money, weren’t selling as many as me because they weren’t me, but they were making more bleeding money than I was! [laughs] So this was really getting on my tit, as they say.

So I was faced with this thing: the public really didn’t understand what was a good picture and what wasn’t. There was no way I was going to start trying to teach them. All I wanted to do was give them my best, and hope they could tell the difference between me and Frank Brunner or who-the-hell without having to search out the signature. And I lived in that idealistic lie for a long time. When I found I could sell a shit piece of work just as well as something that meant so much to me, then it seemed like everything started to fall apart. Now, it didn’t fall apart overnight; it was just something that started to gnaw at me over the years. And eventually the muse started to fade, she started to go away because I no longer had the faith that kept me driving along.

And this thing about Machine Man, yeah, it surprised the shit out of me too. It just happened to be there; I didn’t even know what Machine Man was. I didn’t know it was one of Jack Kirby’s lesser characters. And Herb Trimpe told me that it was going to be a really great series like Blade Runner, and I thought, “Fuck, that sounds good!” And of course it was nothing bleeding of the kind.

GROTH: So you were seriously naïve.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, absolutely. Sure. Fuck, still am.

GROTH: Even after 10 years of The Comics Journal, Barry? I feel like I haven’t done my job here.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I can remember there were years — this was two or three years after I had really given up painting. I wasn’t making any money at all and I was absolutely, bloody broke. The only way I was making money was by selling originals, both paintings and old comic book pages. That’s how I managed to live, and I didn’t live very well. There were times when I could barely afford my rent, and the days seemed to get longer and longer and murkier and murkier and I was getting really confused about what the hell it was I wanted to do. I worked with Oliver Stone on his first film and came back from Hollywood completely disillusioned with Hollywood.

GROTH: The Hand.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right. And I was lost. I was lost spiritually, mentally, financially ... And that went on for a couple of years. I was imagining that I could still draw comic books. But as I was saying, my only connection with comic books was reading The Comics Journal. And God, you depressed the shit out of me, you bastard! [Groth laughs.] Certainly there were times I wanted to write you and say, “Cut it out with that bad news shit! Isn’t there anything good happening?!” And my other connection with comics was that I was good friends with Herb Trimpe. But we didn’t see each other much, he lived about 40 miles down the road, he has a family and I didn’t. So when this Machine Man thing came along — he already knew that I had been trying to draw comics again, just for myself, I wasn’t talking to any companies or anything like that. I was just trying to see if I could do it again. And I was hopeless. I had no sense of rhythm. The whole damn thing was useless. So Herb said, “Look, why don’t you work over my layouts? That will help jump-start you.” And to this day I thank Herbie for being so gracious about it all. It was great of him to let me do it, and furthermore, when he saw me after the first issue just tossing his pages out wholesale and doing them all over, he got a bit upset, and I know he did, poor sod. 'Course it was kind of a blow to him. And eventually I just took over the whole series: I wrote the last story and I was never credited or paid for it. I pretty much took over all the characters and directed the stories from book #2 on. But that was the jump-start that helped me begin to understand the process of comic book storytelling again.

The reason why I wanted to get back into comics was in fact because of The Hand. Because, like so many comic book artists, I’ve always had this desire to be a moviemaker — because it’s a whole lot bleeding easier than writing and drawing comic books — and being out there in Hollywood with Oliver [Stone] and the whole damn thing, I was thinking, “Christ, this is even more bleeding cutthroat than Marvel Comics!” And I didn’t think that could happen! [laughter] So, total disillusionment for me.

In fact I had the option of staying on in Hollywood after the movie was over because I had a bit of money from doing that picture so there was certainly no shortage of cash floating around. But I thought, “Oh, screw this. At least there’s a devil I know in comic books, instead of a devil I don’t know.” Because I was fucking up all over the place in Hollywood — using the wrong terms, I was literally bumping into the walls, I was so naive to the moviemaking process, and the politics of it and the money involved and the kind of people you have to kowtow to. None of that was in my taste at all. It’s disgusting.

GROTH: What is the nature of your naiveté? I’m a bit puzzled by that because you’re an intelligent guy, you’ve got very forceful opinions, you’re strong willed ... I mean, you couldn’t have had illusions about Hollywood could you?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, sure. Certainly naiveté is the word, that’s perfectly correct, but I think something that makes it a little bit more on the money is my romanticism. I romanticize everything, everything in the world — except war or cancer or something. I mean I know dem’s bad things! I know dat! But I’m just such a bloody romantic about everything.

GROTH: Yeah, that could be dangerous.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It is but I’m always going to be that way. I’ve gotten enough scars on me that I know not to pickup that hot poker the wrong way ‘round again, you know? I’ve got caution nowadays. But I still romanticize to such a ... I’m a romantic fool, Gary.

GROTH: [Laughs.] That explains it!

WINDSOR-SMITH: That’s actually my strength as a creator — but it’s my downfall as a guy walking along the same avenue as everybody else.

GROTH: When you got back into comics, you proceeded to ally yourself with some of the biggest sleazebags in the business: Valiant and Malibu.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, blimey, yeah. Shit, talk about naive, yeah. [Groth laughs.] Valiant was... whew. Wow, did I ever fall for that one hook, line, and sinker. You may find this next statement preposterous but Valiant was a better company when Shooter was guiding it. I know how you feel about Shooter and I feel that much of your criticism is valid but, y’know, there are sharks in the water that get eaten by bigger sharks still. I was riding downtown with Jim and one of his loyal assistants and for some reason or other I brought the Journal into the conversation, I’d suggested TCJ might want to do an article on the new Valiant or something or other. The loyal assistant said “But Gary Groth’s such a sleazebag!” “No he’s not,” I replied he just calls a spade a spade.” Our conversation in the cab ride dropped to a menacing silence. Maybe that’s why Shooter didn’t trust me after that; I’d heard from grossly unreliable sources that he wanted me fired from Valiant: Me, the only real creator they had!

As you probably know, I called [Valiant President] Steve Masarsky “Saddam Masarsky.” Never better an epithet was overlaid on another human being! Saddam Masarsky … Boy, when that first rolled off my tongue by accident, and it was literally an associative thing — I thought it was a real hoot! I’ve never referred to him as anything else since then, and now other people call him Saddam too, which always gives me a giggle.

GROTH: So you had a real blind spot to the kind of cutthroat mentality that pervades business.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, yeah. Listen, I can be lied to just like everybody else. Even though at the time of this Valiant thing — I mean, I turned out good work for the company, that was one of the good things about it, and I learned that I can carry a story all on my own, I don’t need a second-rate writer to put in second-rate words for me, I can do it myself, thank you very much. [Groth laughs.] So that was a positive thing that came out of it. And the other positive thing really, trying to stretch the philosophy a bit, is that... [he pauses, then laughs.] Oh, I just got a laugh to myself. I was just thinking, “I’ll never be that stupid again.”

GROTH: [Laughs.] Words that will come back to haunt you.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Words that are going to come back to haunt me probably by this afternoon! But let’s be generous and call it a “learning experience.” So I came out of that with more scars ... But no less ideal, I tell you!

GROTH: Well, you had a lot of learning experiences.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, oh yeah.

GROTH: Twice at Marvel...

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yep. If I were smarter, I would just take one blow from one protagonist and then move on to the next protagonist. But sometimes I actually go back to get hit again. [Laughter.] Maybe I just don’t think I’m learning enough. But at this point in my career, I keep as much control over everything as I can. And I’m in relatively good hands with Dark Horse.

GROTH: Relatively good hands at Dark Horse? Why the qualification?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well... I can sort of nod and wink about that one over the phone, can’t we? I don’t want to say anything derogatory about my esteemed publisher, or his wonderful outfit.

GROTH: Could you talk about publishers in general?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh publishers, publishers, shit...

GROTH: A necessary — or even an unnecessary — evil?

WINDSOR-SMITH: They are a necessary evil. I certainly know — and I mean this truly and I’m honestly not vacillating here — but Mike [Richardson] absolutely adores my work and I’m very proud of that. He has always wanted to publish me … You know, Gary, this is probably something I’m going to write in.

GROTH: [Laughs.] OK.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Over 30 or so years I’ve known only varying degrees of villainy from publishers. But, although Mike Richardson has not fully lived up to his promises to me as yet, I have to say that he is the most authentically sincere publisher I have met at this time. Stan Lee was such a showman, a carnival barker as you depicted him on one of your covers, that there was no question that he had tricks up his sleeve and that you’d never get your monies worth if you believed his megaphone hyperbole. Saddam Massarsky: two parts Richard Nixon to one part Fagin. What a mix: everything about Massarsky’s body language said shyster/lawyer to me.

GROTH: At least you have an attorney to play hardball you now.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right, I have an attorney. It’s not as if I’ve not had legal representation before but they’ve never been comics-hip y’know? And Harris [Miller] is a gas, he knows far more about my work than I do, he’s got a memory like a computer and his favorite character of mine, out of the hundreds I’ve created, is Starr Saxon from some Daredevil story I concocted in 1968! Harris is terrific but he can be a little old lady, too — and you can print that because I don’t care and he’ll just chuckle anyway, I call him a little old lady all the time. “Stop whining, Harris, you ninny!” [laughter] But he always gets back at me somehow — usually by kindness, you know? [laughs]

GROTH: That seems a little underhanded of him!

WINDSOR-SMITH: He’s a devilish manipulator of Romantic fools, he really is. But anyway, Harris is helping lead me along here, and I’m learning a lot more because I’m keeping my eyes open, I’m keeping my ears a bit more open. And the thing about the stuff with Storyteller is, this is my big investment. It’s still entertainment — I’m not telling the story of my life here — well I am to some degree, almost every one of my characters, be they male or female, have something to do with me, one of my many complex sides, you know? So there’s a lot of self-expression going on and some of these characters have been with me for 10 years, or even longer. I’ve been developing them slowly over the years. So, I don’t want to sound too melodramatic about it, but if Storyteller doesn’t make it, I’ve got nothing else to do in this field; I’ll go somewhere else.

GROTH: Well, l can’t imagine that it’s not going to be pretty successful.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, look at the situation. Paper costs more, distribution — look at this whole fucking distribution situation, you know? If this thing holds even for a while, then it will carry on. But this couldn’t be a worse time in this field to bring out such personally-oriented book of a nature like this. I mean, I’m sitting here looking at three beautiful color posters of three of my characters, and they don’t look anything like the stuff that sells at Image, I’ll tell ya. Not even close. One guys overweight and the other girl barely has breasts. And there are no big guns anywhere!

GROTH: I would describe at least two of the three strips in Storyteller as screwball comedy masquerading as genre.

WINDSOR-SMITH: There you go, pretty good. Can I use that line? I’ll put a little “G.G.” under it so everybody knows.

GROTH: Yeah, “G.G.”

WINDSOR-SMITH: Right, got it.

GROTH: The only work of yours in the past that seemed to presage this was the Archer and Armstrong stuff.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Because I thought I would never get to the stage where I thought that the Freebooters, which had a different name in those days, called The Journals of Aran, or something, I never thought I would ever get to the stage in my career where I would be able to pull this sort of thing off all on my own. When I was doing Archer and Armstrong I just started to adapt from a 10-year-old set of characters — characters from what is now called The Freebooters. I thought this was the only way I could get that kind of material out in front of the public, this sort of humorous stuff, fairly sophisticated adult-oriented humor. So I’m actually sorry that I cannibalized myself on that. But one of the things it did prove to me, Gary, was — this is a very upbeat point — when I was writing and drawing Archer and Armstrong, regular people, regular folk started reading my comic books! This is kind of mitigated by the fact that the guy knew me anyway, but nevertheless, he’d never read comic books, and he had heard about Archer and Armstrong, he was the partner of my hairdresser, Sergio, a real sweet guy. And I was having Rita do my hair one day — what’s left of the bleeding stuff [Groth laughs] — and Sergio said, “I really love Archer and Armstrong.” I could have fucking jumped through the ceiling when he said that! He’d heard about Archer and Armstrong, and it turned out it was by me, of all bloody things. He always knew I was a comic book artist but he never knew what I did because he wasn’t into comics. So he started collecting them! And he was telling me, “That scene, so-and-so on page three had me cracked up!” And I just felt like a trillion dollars! I felt like I had made the biggest breakthrough ever. I’ve always wanted the common person to read one of my books and be able to understand it and even laugh at it or something, you know? It was an absolute fabulous thrill to me. In fact, to tell you the truth, I thought he was having me on for the first 10 minutes. [Groth laughs] I thought he was just being really wry with me. But no, it was true. He had heard about this thing from somewhere else, this comic called Archer and Armstrong that adults could read, so he goes ‘round, buys the comic, and says, “Christ Al-bloody-mighty! It’s by that customer of Rita’s!” He couldn’t believe it, what a coincidence.

GROTH: It does feel especially gratifying when someone who’s not a congenital comics fan reads a book...

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, yeah, it’s a gas! I still get a thrill every time I think about it, and this was probably five years ago. I visited the comics shop where Sergio had bought the book and I puttered about looking for anything interesting. Eventually I gave up and just bought a copy of my own work, Archer and Armstrong #5 or something, as I had no copies of it. The lady behind the counter said “You’re gonna love that, it’s the best comic on the market. It’s hilarious.” I autographed the cover and handed it to her, thanking her for her support. Before she had a chance to question me I left the store. I was grinning to myself, I tell ya. This is what I’m hoping for Storyteller. I used to get letters from Archer and Armstrong fans who just didn’t read comic books, but they adored Archer and Armstrong. Because they weren’t being written down to.

GROTH: The big obstacle is finding those people. Because they don’t go into comic book stores because they don’t read comics.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I’ve got all these fancy plans — whether they come to life, I don’t know, it’s all down to the bloody dollar as it always is — but I want to advertise ... We’re advertising in Wizard, you know? I mean, fuck, OK, do it. Advertise in Wizard, why not? Wizard is about comic books. But that’s preaching to the choir. Why not advertise in college newspapers? Advertising by itself really isn’t going to mean that much, but if I could put a really good joke in a college newspaper, something that doesn’t insult somebody’s intelligence, or a really pretty drawing that has that attractiveness that is somehow universal. Sometimes I come up with pictures that are universal — not all the bloody time. It’s kind of hit and miss with me, kind of like Neil Young songs, you know? He’ll come up with a song that will absolutely touch the whole world — and then he does something else that everybody thinks is a piece of dreck. So I had this ideal idea, which again, is on the shaky basis of money, of advertising Storyteller in entirely different mediums. And also if I could just keep going long enough. My first contract with Dark Horse is for 12 issues, and if I haven’t picked up some new and original readers inside of 12 32-page issues, that have more toilet jokes than you can shake a stick at — [laughs] I’m just joking. No actually, I keep doing toilet jokes and I wish I wouldn’t — that’s what comes from growing up in England with Benny Hill on the TV.

GROTH: Well, that’s the thing that’s going to sell it.

WINDSOR-SMITH: [Laughs.] It might. It certainly isn’t going to be the big guns. I try to elevate myself slightly above toilet jokes if I can, but I’ve got to admit there are a lot of them. I’m just hoping I’ll find whatever vacuum was left when Archer and Armstrong died. I’m hoping to find those people again. And I’m going to need even more than that to make this thing a winner. I mean, I need this thing to last for the rest of my career. This is all I want to do.

COMMERCIAL SUCCESS

GROTH: What kind of sales are you talking about in terms of it being a winner? What do you look forward to?

WINDSOR-SMITH: To break even?

GROTH: Yeah.

WINDSOR-SMITH: It’s very, very low. It was probably my naiveté, I don’t know, but I was looking at at least 100,000 for the first issue, and my publishers aren’t looking at anything like that, and they know more about this than me — they’re looking for half of that. And I’m thinking, “Crumbs, it’s 50,000 — that’s going to be considered a success?”

GROTH: That will be considered a raging success, Barry.

WINDSOR-SMITH: That will be a raging, bleeding success. So, what on earth has happened to this field?

GROTH: It collapsed.

WINDSOR-SMITH: My hope — it’s a thin one — but the hope is that it will build. I know that certain good commercial material, certainly stuff that’s coming out of Dark Horse, has built an audience. Like Mike Mignola’s Hellboy. The first three or four issues I don’t even think they broke [even], but it’s built, so I’ve been told, and now it’s in a healthy sales rate — all comparative, of course. And that thing has fairly high publishing costs, it’s full-color, blah, blah, blah. So that’s a good sign. Because I think Hellboy is a really neat little comic book. And Mignola is just transmogrified from it. He used to be this sort of Marvel done thing a long time ago, but he just got better and better and better. And even though his scripting is minimalistic, there actually is some depth to what he’s doing. Because it isn’t just out of his head; it seems like he’s pulling imagery and sensibility from somewhere very arcane ... Whereas Charles Vess is actually illustrating all the stories, all the scenes, fairytale, stuff like this, in a very mundane way, as if you’re supposed to understand everything about it. But it seems to me that Mignola is just acknowledging old folklore and going his own way with it. I admire it for that. I think it’s quite a strong book.

GROTH: I think you have one thing going for you and one thing going against you in the book. When l got the package of the first two issues, what put me off initially, and I’ll be entirely honest with you, was the genres. One was science fiction, one was sword and sorcery, and one was a meta-mythological context. I thought, “Well, this is going to be a very serious Conan-esque thing. “I was unenthused. But as soon as I recognized the book’s humor, I couldn’t stop reading!

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, fabulous. I’m glad to hear that.

GROTH: Now, I have a feeling that the public is going to feel exactly the opposite.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh. [Laughs.]

GROTH: They’re going to be real excited because it’s the genre material that’s sort of standard comic book genres —

WINDSOR-SMITH: But wait a minute, Gary. Why would the public be excited about standard stuff?

GROTH: Because public appetites are habituated, and they want to see the same thing over and over.

WINDSOR-SMITH: But [what is] standard stuff? For one, there is no sword and sorcery stuff out there, so that’s not standard, and the Kirby-esque book, Young Gods, there’s nothing like that out there because Kirby doesn’t exist any more. So what is standard nowadays? Of course it’s what we continually use as the perfect put-down: the tits, the guns ... Even the very fact that Image comics have such a high-end production look to them, you know? What I’m doing with Storyteller is going the absolutely bloody opposite way. All these things are hand-painted.

I could be very slick at times if I want to, but I have no interest in being slick whatsoever, so I let my brush show. I don’t know if you know all this crap about when hand coloring comics editors tell you you should never let the reader know that somebody actually did it that way, as if it should be magically colored somehow — to which I say, “Bullshit.” If I get splashes of paint on the shit, it fucking stays there! [laughs] It isn’t quite that bad; I’m not being sloppy for slopp’s sake. I’m just trying to make this thing as gritty and real, as opposed to admittedly these absolutely fine effects that I see in Wildcats or something like that. That has some absolutely fabulous production, but it has no soul to it. God, I sound old-fashioned when I say, “Shit like that has no soul!”

GROTH: [laughs] The old-fashioned humanist.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, humanism. That’s the thing.

GROTH: Completely out of fashion now.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Totally out of fashion. So that’s the risk here. So anyway, I don’t think people are going to be excited that this is like genre.

GROTH: I think they II be more open to it than if it weren’t. But on the other hand, I also think that fans are such cases of arrested development that they want these moronic contexts to be steeped in seriousness.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yes, I know. Getting back to what we were saying at the beginning of this: how can you sustain an entire industry when your audience is that ... I can’t think of an adjective! ... that imbecilic? People of good conscience are sitting around scratching their heads asking, “Why can’t we break through? Why haven’t we broken through yet?” But look at our bleeding audience! This is the audience that we have attracted! We created that audience, the comic book industry as a whole. If the audience is moronic, it’s because the fucking product is moronic!

GROTH: Yeah, but also we’ve seen maybe the most creatively mature comics ever published over the last 20 years. And we still can’t break the perception among the public that the comics are sub-literate kids’stuff. My son went to Children’s Hospital yesterday, (it wasn’t too serious), but one of the funny things I noticed as we were on our way to the pharmacy was a wing for kids who stay overnight, and each of the rooms are labeled outside the room with titles like “Respiratory,” and so on, and the labels are in word balloons. And why are they in word balloons? Because word balloons means comics, of course, and comics mean kids’stuff. [Laughs.] So this observation was going through my mind even as I was preoccupied by my son’s inability to breathe. But the prejudice against comics is so widespread, and it seems impossible to change. My biggest fear if I were you is based on the fact that the work you are doing now is clearly the most sophisticated work you’ve ever done, and it’s going to appeal to an older, more literate readership, which of course comics don’t have in huge numbers.

WINDSOR-SMITH: This is the big risk in trying to find an audience, rather than working for an existing audience. I’m doing it to hopefully create an audience.

GROTH: And that is a risk.

WINDSOR-SMITH: The biggest risk I’ve ever taken. But you know what? I haven’t got any choice either. I’m not saying I’m doing this because I have no choice. I’m saying that, once I realized that that’s all there is, because I can’t do Machine Man again, I can’t fall to that anymore. And I can’t be Gil Kane in 25 years’time saying, “Golly, I wish I’d have done something more valid. Look at all the books I read, too.” If that happens to me, I’d rather die before I get old. But then again, when you think about it, shit, I think about what Gil said — he was trying to reach another audience with Blackmark.

GROTH: In his time he was certainly, trying to reach a different audience and trying to break out of the commercial boundaries the comics industry created.

WINDSOR-SMITH: There was actually more of a chance in those days than there is today.

GROTH: Do you think so? Even with something like Maus out there?

WINDSOR-SMITH: It just seems like there’s so little choice today. Because it’s all been boiled down — once it was a soup, and now... You know what a “reduction” is? When you’re making a sauce you have to reduce, you have to keep reducing until you’ve got some formula, some consistency. And the potpourri of comic books, or the possible readers of comic books have been reduced to the gross cliché that is everything you see from Image Comics. No matter whether it’s competently drawn by Jim Lee or the most inept thing you’ve ever seen, which is a large portion of what they put out, and for that I loathe them -— I mean as a unit: I don’t dislike any of them personally. But what they’ve done is, they’ve turned the worst of Marvel and turned it into a very smooth paste indeed. It doesn’t help. It doesn’t help people like me who are in the commercial side of the field but want it to be better.

GROTH: When you say the “commercial side” of the field, are you making a distinction between a commercial side of comics and something else?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, oh sure. I’m not driven by money by any means. If I was I wouldn’t do what I do. But I am looking for success, I need success. That’s why I mean commercial. On the back of Storyteller you’re going to see one of those little bar codes, you know? I figure I could get away with that because obviously my intent is honest enough. But I don’t see being commercial as being the death knell of anything. As long as you just don’t fall for the bullshit. If you think about rock musicians — I mentioned Neil Young, but John Lennon, whomever, people of integrity — whose music is full of integrity for better or worse. It just depends upon one’s taste. But their music is conveyed through a commercial process which is CDs or records. That’s what I mean by me being on a commercial side of it. If I wasn’t commercial in anyway I’d be doing little black-and-white drawings and self-publishing probably, and probably at a loss. And telling the story of my life, of which there is much to tell. Explaining how unsympathetic I find the 20th century, or whatever. That would then be non-commercial.

MISUNDERSTOOD

GROTH: Toward the beginning of this interview you said something to the effect that “If the work I was doing was just for me, then gee, my work would be a whole different animal.” I’m curious as to what kind of animal that would be.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I honestly don’t quite really know. Sometimes I scare myself ... I’m capable of a lot of things, artistically. I write an awful lot of material that is never published, and it’s not intended to be. Admittedly, since the advent of Storyteller I haven’t really drawn a great deal for myself. Drawing for me, manipulating the pen on paper, is commonplace, it’s like breathing. I do it all the time and I really don’t think about it any more. Now that I’ve found this venue — or I created this venue I should say — where I can put together all of my things that I do graphically, I’m perfectly glad and happy, and fucking relieved, to be able to harness all of this material and make it palatable. Within my judgment, I’m not pandering to anybody. But there have been many, many times where, when I create simply for myself, I do not do the sort of things that you see published by me. I mean, I’ve seen people’s sketchbooks, and often what they’re drawing in their sketchbooks is what they’re drawing in their comic books for cryin’out loud. So why the hell do you have a sketchbook? You do those sketch things at the back of the Journal, and unless I’m mistaken, I don’t think you’ve really done sketchbooks by the big professional comics types. You usually go for the more...

GROTH: ... more obscure.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Obscure. So I’m not really surprised by what I see because I wasn’t expecting anything. I’ve often wondered what John Buscema’s sketchbook looks like — to go back to that thing for a while.

GROTH: Assuming he does drawing that does not generate cash.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I assume that he’s a professional artist right there and then and probably puts the pencil down at five o’clock. Picks it up at 8:45 precisely.

GROTH: That’s right. So what do your sketchbooks look like?

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, as I say, they’re certainly not like anything of mine you’ve seen. I haven’t done sketchbook work for quite some time...

GROTH: [Laughs.] I can’t imagine you have time to do sketchbook work!

WINDSOR-SMITH: Quite so. If you have a natural ability to create marks that mean something, a sketchbook for me was pretty much like scribbling in a diary, quite literally almost, page for page. I’ve got sketchbooks from the early-’70s right through to '88, '89. I really don’t like looking at them. Sure there are some nice drawings in there of projects, the original drawings for Pandora’s hand, a study or something like that. And I’ve got plenty of nice drawings like that. But it’s when I let my mind flow. We all have our dark side — and some of us darker than others. I definitely have a dark side. And I would give that dark side free rein. At this vantage point, 1996, looking back on certain pages of a sketchbook of say, ten years ago, I would look at this stuff and say, “My God! Was I depressed then?” I’m saying that it’s a graphic depiction of depression. Not somebody holding his head with tears coming out of his eyes, or anything so inane, but it could be just as much as a few scribbled lines on a page, or one line on a page. And it’s that spirit that comes out. There is a word for this kind of stuff, I’ve forgotten what it is, some multiple-ology sort of word, about how one can project one’s spiritual sense on an object or whatever. It may be pure idiocy for all I know, but I did hear a word once that described that. Because I was telling somebody about it, and they said, “Oh yes, that’s so- and-so-ology, isn’t it?” But*now I’ve forgotten what the word is. But I can literally open some of those sketchbooks and still get almost exactly the same thoughts crash back into my head — even though they were ten or more years gone. And if I hadn’t opened that page I’d have completely forgotten how I’d felt or what I was thinking at that precise moment that I scribbled something, that is indecipherable to anybody else but me. I’ve always found that to be fascinating. Have you ever picked up an antique and felt suddenly forlorn? And you don’t know why?

GROTH: Mmm-hmm.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Or you’ve walked past a house and realized that something happened in that house — and I’m not saying something like a B-movie, where everybody was slaughtered or something. But just get an ineffable sense of something...

GROTH: Sure.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I’m glad you understand that. I could say that to a half dozen people and they’d go, “What the fuck is he talking about?” I know that stuff happens. I can’t explain it ... But my sketchbooks — especially because the ‘80s was such a dark period for me — are filled with darkness.

GROTH: Why do you think that the subject matter or the context that you established in your sketchbooks wouldn’t be appropriate to be published?

WINDSOR-SMITH: I’ve thought of this often ... that I’m not really being true to myself. There is a validity to that material, I do strongly believe it. And because I’m not letting it out to the public, am I sort of being coy? Am I afraid? Am I afraid to let people know how I really feel? Or — and this is just as valid as anything else — am I saying to myself, ‘Well, that’s how I was. So why do I need now to bring it up again?” But I’ve thought of it often. Often, when I’m looking through things like RAW or more personable comics ventures, I think, “Gosh, I really understand how that guy feels.” Not by what he’s written, and not by the unison of what he’s drawn and written. But how the heck he did it. Something about how he did it. And I always find myself being moved — I’m not saying this in a good way or in a bad way — but it touches something. And that’s the spiritual thing that you really can’t deny. Well, you can and many people do. Most people deny this stuff continuously. They think it’s getting to vapors, or they think ... God knows what they think. But a lot of people — from my experience — will just get scared when they think of anything that’s outside of what you can see and smell and touch right in front of you. When I do this sort of thing, there is no academic quality to it at all. These are drawings, but they’re not what I normally do. These works are not my controlled self. Certain friends of mine have seen this stuff, certain intimates, and naturally they’re probably the same intimates who know the dark side of me. So there is a certain safety, because they already know me, as I know them.

GROTH: You re clearly investing yourself — or part of yourself — into the work you’re doing right now with Storyteller. But it also seems as if you require a certain commercial mash that you have to shape it into a commercial mode to be comfortable.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Possibly. But as I said to you, Gary, I’m not pandering in any way.

GROTH: I’m not suggesting you are. My point —

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, my sense of this is, Yes, I do want it to be commercially successful, but if you don’t like it, well, fuck you. [Groth laughs.] And I’ll go ahead and do something else, but I won’t do it for you; I’ll do it for me.” But what I think it is, is possibly a fear of losing control. That sounds right as I say it. To make yourself naked, to really show yourself, warts and all, to use that stupid cliché — that takes a lot of fucking guts. If that was the only outlet I had, if that was the only way I could do it — like Mike Diana. Now, here’s a guy...

GROTH: He has no inhibitions whatsoever.

WINDSOR-SMITH: No inhibitions, and he has a lot of natural talent, but he has little learning. He doesn’t have craft, except for what he’s sort of picked up here and there. But this sort of ruling, this edict, that he may not draw comics again that came down from the court — you can’t imagine how that makes my head spin. This is Orwellian. Or worse.

GROTH: Yeah, it’s ugly. And probably unconstitutional.

WINDSOR-SMITH: The thing is, with Diana, that is his method. That’s his method of exploring himself and of explaining himself, you know? Of course we can’t help but say, yes, it’s unfortunate to some degree that these images are so radically disturbing. But he’s a child of our culture. And he lives in fucking Florida for crying out loud! [Groth laughs.] So people should be looking to themselves; not toward Diana but at the culture that Diana was born into. And people who judge him should judge themselves first. I know this sounds absurdly Biblical, but there you go. The thing is that that’s Diana’s only outlet. Me, I have got many levels of outlet. And the controlled stuff, the Storyteller, the other gear that I’ve done over the years, is for me, more satisfying at this time. I would like to think that some time in the future I will have an audience understand me well enough — and I hope it comes through Storyteller, because I’m getting closer and closer to the real me all the time — that there will be an audience, and it probably will be just a small bunch, it won’t be everybody who likes the fun and laughter of “Freebooters,” who will accept the other side and gratefully look at it. They may not like it, and I’m not asking them to. I just don’t think I have the audience for it.

I don’t want to be misunderstood. Everybody is in danger of being misunderstood in this culture. I’d be very much in the same position as Mike Diana if I wasn’t so self-restricting, if I wasn’t born to the hypocritical, practically Victorian "ideals" that were foisted on me as a child: can I throw out another music/comics synonym? John Lennon spent half a dozen years trying to re-write the love ballads from the '50s and early '60s, y’know ... the pathetic Roy Orbison or Tin Pan Alley teen tunes thing and although he degraded his later Beatles stuff that was really inspired he claimed, and I agree with him, that he only really came alive when he produced the works that many people, Beatles fans and the like, just can’t understand, get behind or grok; stuff like Two Virgins (with Yoko Ono) and, really his best work ever was John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band: that was the real John Lennon with warts and all. He was only allowed to be really himself and, by that grace, learn to live and be in love and to be a parent and all that because the world had previously paid homage to him as a Beatle, be it mop-top shit or, as I say, his latter work before the Beatles split. For some court judgment to effectively pronounce that a young artist is not allowed by law to investigate himself and the world around him, is not allowed to create or re-create the god-awful modern world he was born into is the most disgraceful crime committed upon a free man in America. Mike Diana should not be facing jail or whatever the hell it is those malicious appointed bastards have threatened him with. Diana should be vindicated by everybody, every soul who suffers in this fucked-up society but who hasn’t got Diana’s talent for expression. The fucking judge should be sent to jail for being a posturing blind-eyed pissant posing as a man of integrity! This fucking planet is losing itself, I tell ya!

BACK ON THE ROAD

GROTH: This might be a good place for me to ask you what think of Crumb, because the classic example that comes to mind in this context of course, is Crumb’s sketchbook which are as unmediated an artistic expression as I can think of.

WINDSOR-SMITH: I’m not as culturally involved with Crumb as a lot of people are of my age, or maybe a little bit older than me. I wasn’t in the States when Crumb was doing his initial work, Zap, and all that sort of thing. Because I was a creature from the commercial comics, I viewed with suspicion the underground material. I was a wholly different person back in those days. I was pretty uptight. And a friend of mine brought back some black and white Zaps and stuff like that from the States, and he was thrilled to pieces by them. I couldn’t comprehend it. Because I was so caught up in what I was doing, my intention to be second only to Jack Kirby or some immature goal like that. I certainly understand Crumb nowadays and have for a long time. But at that time, I couldn’t comprehend the need to expose your every thought. I thought that things had to be controlled. Now obviously I still have quite a lot of that about me. But it’s with a knowledge, and it’s with an understanding of what I’m doing rather than just following some archetype. Today, I adore Crumb. He is a fantastically important artist. He is still working with energy. You know I’ve never seen that bloody film yet?

GROTH: Oh really. You should see it. [Laughs.] It’s amazing.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yeah, I know. We here at the studio kept trying to make a date to go see it because it was around here at one of the art theaters, but something would always come up to kill the plan.

In a nutshell, I don’t know if I appreciate Crumb as much as people who are more his contemporary and more his type of creator. But I certainly think I give him tons of respect.

GROTH: You recently made a distinction to me in casual conversation between yourself and what you referred to as the kinds of cartoonists I publish.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Yes.

GROTH: And I sort of understood what you meant, but on the other hand, you are expressing yourself, and you re moving closer to Crumb territory in the sense that I think you’re expressing the themes and ideas that are most important to your life.

WINDSOR-SMITH: Oh, sure.

GROTH: But I was wondering if you could elaborate on what you meant by making that distinction between yourself—

WINDSOR-SMITH: Well, I noticed that you noticed this at the time. I don’t think I’m being particularly kind to myself when I say that I’m a commercial artist but after all, I am the bloke who created Weapon X, I did do fucking Avengers #100 for crying out loud. [Groth laughs.] And if that isn’t bleedin’ commercial, I don’t know what is! But it was a mindlessness on my part. Even though I always put my little personal things into that kind of material — although with the Avengers there was nothing personal about that for me. But it was a young journeyman thing, so it was done with vigor. But it has no validity to me or my life or my career. Even though I said that, and I do mean it, it’s less true today than it has been in the past. Yes, I am moving toward something more personally sophisticated. I’m not there yet. With each book of Storyteller — and it’s not as if I’m doing this deliberately either— I’m trying to forge ahead in some sort of way of explaining myself to myself. It’s a theme that has come up many times between you and me as we talk: Which is, as you get older, you get wiser. As you get older, you need more substance to whatever it may be, whether it’s creative, whether it’s your marriage; it’s any number of goddamn things. The kind of people you enjoy talking to today are wholly different types than the people you enjoyed talking to 15 years ago.