1.

Reading a comic book once made me sick. Like other Baby Boomer kids, I fell in love with Silver Age Marvel Comics, especially the Kirby/Lee/Sinnott Fantastic Four. I was imprinted by Lee’s narrative voice (simultaneously melodramatic and folksy) and Kirby’s visual imagination: the Marvel aesthetic became my be-all-and-end-all, my standard for quality comics. One day, though, a friend left some comics at my house, and the next morning I casually picked a non-Marvel from his stack to read at breakfast. I started eating and reading: the comic was a weird pre-Code horror anthology, and the first story featured inky, crosshatched illustrations (a lesser artist channeling Creepy-era Reed Crandall, maybe) for a disturbing story about a woman who turns herself into a leopard. I hated it because it wasn’t a Marvel comic. I glanced at panels where the woman, with a human head and leopard’s body, prowled over her unconscious lover. I felt nauseous. I threw the comic and my cereal away.

Why did I get sick? Why was I so invested in Marvel, and why and how did this leopard-woman horror comic upset my tastes so traumatically? What does it mean to read a new comic?

2.

I’ve been thinking about these and other questions, mulling over how my personal responses to comics (nausea or otherwise) inform the criticism and research I write. I’ve realized that the idea of newness is important to me. I read for those moments where I have my preconceptions upended, my notions of what comics do irrevocably altered. The leopard woman jerked me out of Marvel complacency; Crumb’s Homegrown Funnies (1971) introduced me to the Id-fueled underground; Kramers Ergot #4 (2003) uncoupled me from narrative, leading me to attend to the formal qualities (the colors, shapes and forms) of comic art. It sometimes takes a while for my paradigms to shift—it took several re-reads before I saw that Kramers #4 was something more than a collection of self-indulgent doodles—but shift they eventually do, and that shift is, for me, the most exciting result of following an art form closely.

One of the aesthetic theories that best captures that sense of expanding perceptions is Hans Robert Jauss’ idea of the horizon of expectations. Jauss (1921-1997) was a German literary scholar who argued that both readers/spectators and works of art are influenced by material, aesthetic and political contexts. These contexts create a “horizon of expectations,” a baseline against which the art in question stands as conventional, amateurish or innovative. (Kramers #4 was a paradigm-shifter because eight years ago, almost all comics, mainstream and alternative, prioritized narrative.) This emphasis on context may seem obvious, especially in our Po-mo, theoretically savvy culture, but it still informs the criticism I write, especially my belief that critics should go beyond simple “bad/good” evaluations (“This issue of Batman sucks!”) and position the comic against the broader backgrounds of aesthetic and ideological norms.

3.

In his seminal essay “Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory” (1967), Jauss develops his arguments about the horizon of expectations by talking about time. He points out that changes in society and the zeitgeist create ever-shifting horizons of reception and analysis. Readers of Kramers #4 in 2003 interpreted the anthology differently than those who read it today, because Kramers #4 was followed by other significant books (later issues of Kramers, as well as Abstract Comics [2009], and Yuichi Yokoyama’s Color Engineering [2011]) that cultivated a wider acceptance of comics that emphasize the qualities of the picture plane. For Jauss, the meaning(s) of a text are in large measure determined by colliding discourses and forces from both the past and present:

The quality and rank of a literary work result neither from the biographic conditions of its origin, nor from its place in the sequence of the development of a genre alone, but rather from the criteria of influence, reception, and posthumous fame.

When studying an older text, the critic should consider both the environment of initial reception (I bought Kramers #4 at the 2003 San Diego Comicon, oddly enough) and how discourses of “influence, reception, and posthumous fame”—including coverage and commentary from the Journal—have molded our reception of the text since. And then our hypothetical critic writes a review or article that becomes part of the cloud of interpretations swirling around the text, influencing future readers and critics.

All this happens on a personal level, especially in our 21st-century saturated media landscape. Back when I was reading those Kirby/Lee Fantastic Fours, I felt like I was keeping up with most comics, and with the broader currents of comics culture, but I’ve since been humbled. I’m unable to keep pace with the flood of comics and graphic novels currently being published, and I understand that though I’ve been reading comics for over 40 years, I’ve inadvertently ignored hundreds of key creators, genres and companies. The history of comics is deep and vast, and I’m a haphazard disciple, which is why Jauss’ theory of the horizon of expectations, his stress on how past and present discursive contexts create the meaning of a text, is useful for my dives into comics’ oceanic past.

4.

Early in February 2011, I met my friend Toney Frazier for our weekly lunch. Generous about sharing his enthusiasms (offbeat ‘70s music, the horror genre, underground comix), Toney often loans me books and brings me gifts, and this time he gave me a copy of Stephen Sennitt’s Ghastly Terror: The Horrible Story of the Horror Comics (Headpress, 1999) that he’d found at a used bookstore. Ghastly Terror is a lively, opinionated survey of the history of American horror comics, from ACG’s Adventures into the Unknown (1948) to the nine-issue run of Stephen Bissette’s Taboo (1988-1995). Sennitt’s approach isn’t academic: he doesn’t interview writers and artists, or research the business practices of publishers like Warren and Eerie. Rather, his focus is almost exclusively on gut-level aesthetic evaluation, on whether or not particular titles and individual comics deserve to be read. In my opinion, Ghastly Terror is most fun when Sennitt delivers judgments that run contrary to fanboy canons—as in his denunciation of the ECs as “too repetitive and unadventurous” (57)—and when he offers up consumer-guide checklists with titles like “Top Ten Warren Mags” and “The Ten Best Horror-Mood Magazines.”

The title of that last list, about the “Horror-Mood Magazines,” refers to the comics (Nightmare, Psycho, Scream) written and edited by Alan Hewetson and produced by Skywald Publishing between 1971 and 1975. Skywald, founded by Marvel Comics production manager Sol Brodsky and investor Israel Waldman in 1970, began by churning out black-and-white horror magazine in imitation of the Warren titles Creepy and Eerie. Sennitt argues, however, that black magic bubbled forth when Hewetson was hired as associate editor of Skywald in 1971: “Under Hewetson’s editorship the Skywalds would develop into the most unique and disturbing horror comics of all time, generating their own particular, coherent world-view which would at least put them on a ‘philosophical’ par with the ECs and the early Warrens” (151). Hewetson himself called his approach the Horror-Mood, described by Sennitt as “a miasmic evil” (151), a “kind of decaying atmosphere” (153) created by the heady mix of Hewetson’s ornate, pseudo-Lovecraftian prose style, and the unsettling images conjured up by Skywald’s stable of artists, many of whom were foreign artists willing to work cheap.

When I first read Sennitt’s description of Skywald’s Horror-Mood, I was intrigued, because I’d never seen or read a Skywald magazine in my life. I’d only read brief mentions of Skywald in the fan press, though somehow I was familiar with the title of one of the most notorious Horror-Mood stories—Hewetson and Ramon Torrents’ “The Filthy Little House of Voodoo” (Psycho #8, September 1972)—even though I hadn’t read the story itself yet. (I suspect that I saw the title in some Comic Reader or Comics Journal article, and then tucked it into my permanent memory because “Filthy Little House of Voodoo” is a great name for a blues band.) But Sennitt’s high praise (“The most unique and disturbing horror comics of all time”!) made shopping for some Skywald magazines a priority for me.

5.

Cut to June 2011. Armed with various Sennitt checklists from Ghastly Terror--“The Ten Best Horror-Mood Magazines,” sure, but also “Ten Essential Tales by Archaic Al [Hewetson],” and a catalog of the stories in Skywald’s “Saga of the Human Gargoyles”—I walked the aisles of the dealers’ auditorium of Charlotte’s Heroes Con with Toney, sniffing at every magazine longbox for hidden caches of Nightmare and Psycho. There were only a few booths that had any Skywalds, however, and most were, by my tightwad standards, outrageously overpriced. I didn’t buy any, although Toney lucked into a dealer who sold him a small stack at a volume discount. I’m tempted to describe the dealer in comically exaggerated terms, as an eldritch presence resembling EC’s Crypt-Keeper, but that would be false and unkind. The guy had long gray hair, but no hood or cloak.

At our next lunch, Toney had another surprise for me: his stack had included two copies of Scream #5 (April 1974), and he gave me one. I was immediately struck by the lurid vibrancy of its cover:

Even before I opened that cover, though, I thought: This is a comic I know very little about. Could I meta-blog my first experience of reading a Skywald, and chronicle both my immediate responses to the comic and the horizons—of expectations, of interpretations— that I brought to Scream #5?

6.

Scream #5 is approximately 8 ½ x 11 in dimensions and is 68 pages long, counting the front and back covers. The cover pages are in color, and the interior is in black-and-white. On the inside front cover, there’s an ad for “Horror-Mood Characters, ” such as the Human Gargoyles, Frankenstein and the Heap, who appear in stories serialized in Nightmare, Psycho and Scream. The ad promises a “blockbuster character being created expressly for our upcoming fourth magazine…Tomb of Horror…you gotta SEE ‘it’ to BELIEVE ‘it.” But this strikes a poignant note: very few saw “it” because Skywald collapsed before Tomb of Horror was published. Facing this ad, on the first interior page, are panels borrowed from each of Scream #5’s stories, alongside the titles of the stories (including “The Conqueror Worm and the Haunted Palace” and “Shift: Vampire”) in handwritten lettering, and typeset text that lists contributors’ names. The kerning of the typeset words is a bit askew.

On pages 14-15, Hewetson includes “A Corrupt Collection of Lunatic Letters from the Macabre Scream Mailbag,” featuring readers feedback, an ad for a future story (“Coming Up Next in the Monster, Monster Saga”), and a bizarre column by Skywald writer Augustine Funnell, who denounces fanzines and the writers contributing to them. Specifically, Funnell is bothered that fans talk more about other fans than the work of comics professionals:

Now before anyone accuses me of hating fandom (which I don’t!), I’ll make my single point. Any professional, whether his name is Hewetson, O’Neil, Smith, Ditko, or Archie Bunker is more important than any fan! Why? Because it’s the pro who’s doing the entertaining! It’s the pro who deserves the credit—not the fan who only reads what the pro does. If the fan was worthy of the professional’s praise, he’d damn well be a pro!

Fans have forgotten their roots. They’ve forgotten who the true heroes are. In a word, fans have become arrogant. (14)

There’s a curious tension among these texts from Scream #5. In Ghastly Terror, Sennitt mentions that Alan Hewetson began his career as an assistant to Stan Lee at Marvel, so it’s no surprise that Hewetson’s bonhomie in the ads and letters pages mimics Lee’s 1960s hype, right down to the nicknames (Archaic Al Hewetson, Awkward Augustine Funnell, etc.) given to every Skywald staffer and freelancer. With his swingin’ prose style, Lee (deceptively) defined the Marvel Bullpen as a rollicking clubhouse that readers could join simply by buying more Marvel comics, and Hewetson sought to build the same playful (and commercial) rapport with fans. Funnell’s screed against fanzines and fans, however, builds a curiously elitist wall between “arrogant” fans and “important” professionals. Why didn’t Funnell realize that most fan publications, especially Amateur Press Associations, were as much about creating a community as they were about reviews of professional comics? Further, history hasn’t upheld Funnell’s implicit comparison of Hewetson with creators like O’Neil, Smith and Ditko; did Funnell believe that Psycho and Scream should be praised as much as key 1970s comics like O’Neil and Adams’ Green Lantern/Green Arrow and Thomas and Smith’s Conan? Whatever the motivation, I can’t imagine Funnell’s jeremiad sat well with either hard-core fans or casual readers looking for a fun horror mag.

7.

I’m also not convinced that any demographic slice of readers would find the comics in Scream #5 worth their money either. The biggest problem is that Hewetson is incapable of dreaming up an original plot. “Get Up and Die Again” is a riff on The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)—where a mad scientist named “Ingles” (wink, wink) bluntly exclaims “This is part of a Frankenstein movie plot…I will engage in so [sic] such melodramatics”—while two of the other stories are Edgar Allen Poe adaptations, another is a version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, and “Shift: Vampire” combines horror and science fiction in a way reminiscent of (but inferior to) the Archie Goodwin-Gray Morrow tale “Blood of Krylon!” in Creepy #7 (February 1966). Based on Scream #5, Hewetson doesn’t so much write and edit stories as he set-arranges swipes and familiar horror tropes into simulacra that almost pass as stories—until you realize that the catharsis and sense of aesthetic form traditionally associated with storytelling is utterly absent from Hewetson’s “scripting.” (As horror fans know, vampires and zombies lack that essential spark of life that defines the truly alive.)

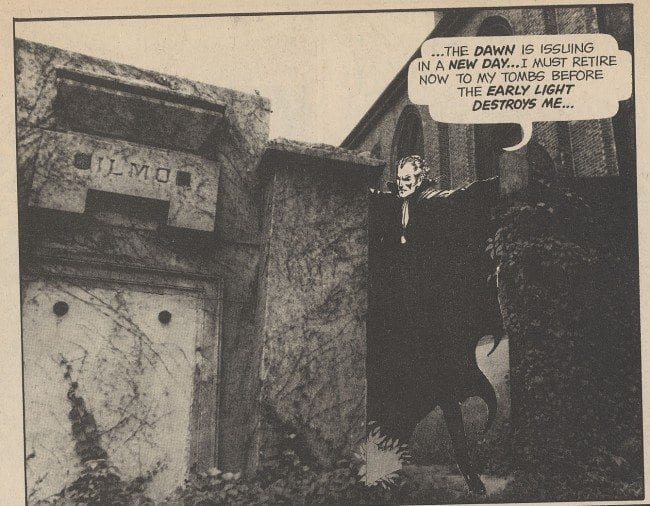

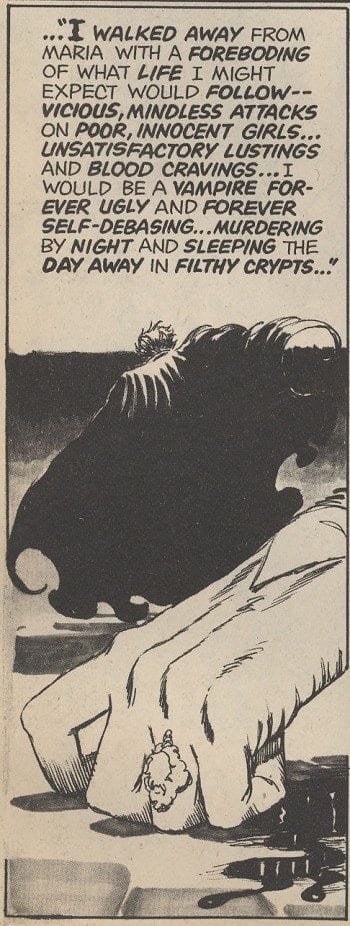

Hewetson’s work is lousy on the panel-by-panel, caption-by-word-balloon micro level too. He labors under the Lovecraftian misbelief that scary writing should be a pile-up of adjectives, as in this panel from Scream #5’s first story, “The Autobiography of a Vampire (Chapter Two)”:

The vampire has just murdered the woman he loved, but we don’t see his face, and Hewetson and artist Ricardo Villamonte never visually illustrate the character preying “on poor, innocent girls” and sleeping “in filthy crypts.” Everything is described rather than shown. Contrary to Sennitt’s feeling that the Skywalds carry “a decaying atmosphere,” I found Hewetson’s storytelling dull and distant rather than lurid and loathsome.

8.

The art in Scream #5 is all OK, although several of the artists exhibit strange stylistic tics. In his work on the adaptation of Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” Maro Nava cuts his spot blacks with filigreed white lines, and draws faces with googly Marty Feldman eyes.

Artist Ricardo Villamonte begins and ends “The Autobiography of a Vampire” with panels that place the drawn central character against photographic foregrounds and backgrounds.

And in “Get Up and Die Again,” Alphonso Font uses manic crosshatching and sculptured negative space to create a convincing, moody gothic atmosphere:

There’s an illustrative density to this art that reminds me of the Filipino cartoonists (Alex Niño, Alfredo Alcala, Rudy Nebres, Tony DeZuniga, etc.) who drew for DC anthology titles and Marvel magazines at roughly the same time that Skywald was in business. Many of the foreign artists who worked for Skywald and Warren, however, were Spanish, and often associated with the Selecciones Illustradas studio in Barcelona. At the conclusion of his essay on “The Spanish Invasion” in Comic Book Artist 1.4 (Spring 1999), David A. Roach argues that although much of this work was accomplished (“the highest expression of a nation’s artistic tradition”), the “invasion” itself was short-lived and influenced few—if any—contemporary comics artists. Scream #5 is a tomb for the ornate Spanish style, for a forgotten visual approach.

9.

Let’s go back in time again, back to the mid-1970s: what is the state of horror in American popular culture at the time of Scream #5’s release? In film, this was an unstable period, as leering vampires and haunted houses were replaced by a “New Horror” (to use Ron Rosenbaum’s term) of greater psychological and visual verisimilitude. The movies of England’s Hammer Studios, especially the entries in their Dracula and Frankenstein series, were widely distributed in the U.S. and represented the most successful example of old-style horror in 1960s cinema. But by the early 1970s, Hammer bottomed out, turning to unregulated sex and gore, and bizarre genre combinations to juice up box office. Personally, I like the Hammer films of this period—I’m still infatuated with Ingrid Pitt in The Vampire Lovers (1970), and inexplicably fond of the Hammer-Golden Harvest co-production The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974), a woebegone attempt to cash in on the Kung-Fu craze—but the Hammer movie monsters were quickly displaced by rawer, more viscerally unsettling movies like Night of the Living Dead (1968) and The Last House on the Left (1972).

In Shock Value (2011), his recent history of “New Horror,” Jason Zinoman characterizes the emerging post-Hammer aesthetic thusly:

In the late sixties, the film industry was changing. Rules about obscenity and violence were in flux. The “Midnight Movie” was reaching a young audience that embraced underground and cult films. Starting in the second half of 1968, the flesh-eating zombie and the remote serial killer emerged as the new dominant movie monsters, the vampire and werewolf of their day. A new emphasis on realism took hold, vying for attention with the fantastical wing of the genre. Just as important was how the writers of these movies shifted the focus away from narrative and towards a deceptively simpler storytelling with a constantly shifting point of view. Movies were more graphic. The relationship with the audience became increasingly confrontational, and that was a result largely of the new class of directors who were making low-budget monies for drive-in theaters and exploitation houses across the country. (6)

Zinoman then offers up a litany of auteurs who reinvented horror both outside and inside Hollywood: Roman Polanski, George Romero, William Friedkin, David Cronenberg, Brian De Palma, John Carpenter, Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper, and others.

10.

Did the “New Horror” infiltrate comics? The color mainstream comics of the era were too constrained by the Comics Code to emulate The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), and the Marvel black-and-white magazines always seemed to me a slightly naughtier version of the mainstream stuff, complete with the same continuing characters (Conan, Dracula, the Hulk) and creators (Roy Thomas, Steve Gerber, John Buscema). And I don’t see any traces of New Horror in Scream #5, just Poe adaptations and Frankenstein monsters.

The only publisher that dips into New Horror during the 1970s is Warren. Although Warren was the best of the black-and-white publishers, its quality is maddeningly inconsistent; Archie Goodwin’s terrific tenure as editor-in-chief and primary writer of the Warren line (1964-67), for instance, was followed by a lackluster, financially unstable period when Creepy and Eerie were rife with reprints from the Goodwin era. Luckily, the emergence of the filmic New Horror coincided with a renaissance at Warren, as Louise Jones Simonson edited the comics (1974-79) and with art director Kim McQuaite modernized the look of the magazines.

Simonson’s skill as an editor, along with Warren’s status as the premiere horror publisher, kept major talents at Creepy and Eerie, talents more in sync with the innovations of New Horror than Hewetson and the Skywald stable. Bruce Jones and Bernie Wrightson’s classic “Jenifer” (Creepy #63, July 1974) isn’t about vampires and werewolves; Jenifer is a new breed of monster that unsettlingly combines hideousness, cannibalism and overwhelming sex appeal, and the story unfolds in naturalistic locales (day-lit woods, a suburban house, a run-down motel) rather than in gothic castles and haunted houses. Another New Horror Warren tale is Jim Stenstrum and Neal Adams’ “Thrillkill” (Creepy #75, November 1975), which emulates Peter Bogdanovich’s film Targets (1968) in taking inspiration from Charles Whitman’s real-life sniper rampage at the University of Texas at Austin in 1966. It’s stories like these that we remember from the 1970s black-and-white magazines—because they represent peak work by important creators, and because they bring the violent, transgressive, experimental vibe of New Horror into comics—while virtually all the Skywald material is forgotten.

(Continued)