***

In 1994, the cartoonist Yoshihiro Togashi put together a free giveaway book for a convention appearance, having just ended the tremendously popular boys' manga series Yū Yū Hakusho. The title had run for three and a half years in Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine, at the blazing zenith of its circulation: over 6 million copies, every week. The giveaway book (translation by medoroa.net) detailed Togashi's dissatisfaction with his life in the swelter of such success: sleepless, his chest aching, Togashi had found himself in a position where any effort he made to relieve his stress would sabotage the breakneck pace of his title's production - 175 chapters would fly out the door in less than 44 months. At times, Togashi confessed, he would send all of his studio assistants away so he could draw sequences entirely on his own, as a means of recovering the satisfaction of being a cartoonist; on a few occasions, he drew everything in only half a day, which pleased him, but brought complaints from readers who could tell such work was not up to the formidable standard of top-tier commercial manga. "I knew that Jump dropped a manga after 10 weeks if the readers surveys proved it to be unpopular," Togashi mused, concluding that nothing he actually wanted to draw for himself would be commercially viable under this system. So, he just stopped - condemning himself for 'selfishness'. His present series, Hunter x Hunter, has released at the more relaxed rate of 390 chapters from 1998 through the present; it has been on hiatus -- not for the first time -- since November of 2018.

In 1994, the cartoonist Yoshihiro Togashi put together a free giveaway book for a convention appearance, having just ended the tremendously popular boys' manga series Yū Yū Hakusho. The title had run for three and a half years in Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine, at the blazing zenith of its circulation: over 6 million copies, every week. The giveaway book (translation by medoroa.net) detailed Togashi's dissatisfaction with his life in the swelter of such success: sleepless, his chest aching, Togashi had found himself in a position where any effort he made to relieve his stress would sabotage the breakneck pace of his title's production - 175 chapters would fly out the door in less than 44 months. At times, Togashi confessed, he would send all of his studio assistants away so he could draw sequences entirely on his own, as a means of recovering the satisfaction of being a cartoonist; on a few occasions, he drew everything in only half a day, which pleased him, but brought complaints from readers who could tell such work was not up to the formidable standard of top-tier commercial manga. "I knew that Jump dropped a manga after 10 weeks if the readers surveys proved it to be unpopular," Togashi mused, concluding that nothing he actually wanted to draw for himself would be commercially viable under this system. So, he just stopped - condemning himself for 'selfishness'. His present series, Hunter x Hunter, has released at the more relaxed rate of 390 chapters from 1998 through the present; it has been on hiatus -- not for the first time -- since November of 2018.

Togashi and the precarious visibility of his work is referenced early on in Downfall ("Reiraku"), a relentless firehose blast of misery from Inio Asano, who has the type of readership which may hail this as a return to form, given that Asano has otherwise been filtering himself lately through the cute SF artifice of the ongoing Dead Dead Demon's Dededede Destruction. A self-contained book, Downfall was serialized throughout the first half of 2017 in Big Comic Superior, an older-targeted sister to Big Comic Spirits, the seinen magazine which has been running Dededede since 2014; it is tempting, therefore, to view Downfall as a deliberate counterpoint to that work - to be sure, the scenario does very little to discourage such reading.

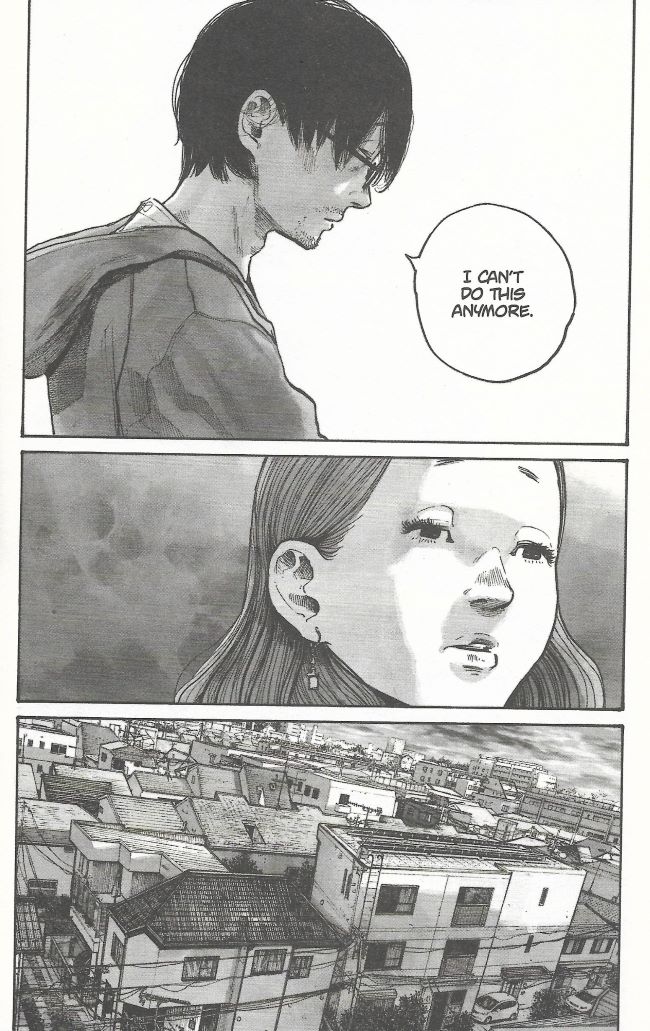

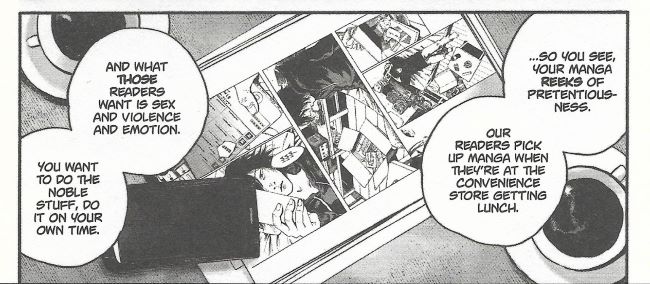

Manga artist Kaoru Fukazawa has recently completed work on the fifteenth and final volume of "Goodbye Sunset" - a "powerful, emotional tale of youth and resilience," per its publisher, which continually slashed its print run as readers fled. Supercilious journalists praise the work's artistic power while snickering about its 30th-place reader poll finish. Fukazawa suspects he's on the outs with his publisher - not yet at the place where they wouldn't work with him anymore, but his editor has advised him to visit only during office hours, like a student. In contrast, Fukazawa's wife, also an editor, is on call at all times to assist a certain artist of popular comics for women, stoking her husband's resentment; Fukazawa is an abusive spouse, deriding his wife's assent to creative mediocrity, then blaming her for not spending time with him. He has been accused of sexual harassment in a professional setting, but has suffered no consequences. Lately, he has taken to visiting sex workers, and has become fixated on a very young woman who reminds him of his university girlfriend, who hated the world as much as him. When told that an author of sentimental comics views him as a great influence, he replies: "So then... my manga's stupid too, I guess." He wants to sell out, badly, so that he might at least profit from the moronic tastes of readers; a SF project, maybe - something starring a cute girl with pigtails.

It will not take any great effort for even casual observers to sense parallels between Fukazawa and Inio Asano, author of Goodnight Punpun -- which alienated not a few Japanese readers and saw its sales accordingly drop -- and the aforementioned Dededede, which in part concerns a twintailed teen romping across an SF background. The book's translator, Jocelyne Allen, further notes that Asano has publicly stated that the story is informed by circumstances from his life, including his divorce from his first wife. The Fukazawa character actually first appeared in chapter 91 of Punpun (vol. 5 of the VIZ edition) as an Asano-like artist whose face was not shown; here, he is drawn in Asano's familiar blonde image in university flashbacks, while in the present-day story he is closer to the dark-haired, stubbly Asano of occasional stray photos. Given that Asano has stated in the past that he makes manga, to some extent, to resolve his own personal doubts and fears, it is extremely easy to see Fukazawa as an autobiographical figure. However, the character also seems simplified. In relating his despair that Japanese readers have lost interest in difficult or complicated stories, Asano nonetheless gives an optimistic view of his own young readership: "I don't mind if they don't understand the story in its entirety. Years will pass, and then those readers will be older and more mature. Maybe then they will read the manga again and understand it in a totally different way."

Nothing so complex comes out of Fukazawa. He derides his young readership as fickle and easily bored, in the same way he derides everything: his comics; his peers; his loved ones; himself. He understands that to consider himself better than others isn't to say that he is any good, but what is left after that? Asano suggests that there is then only work.

There isn't really any 'plot' in Downfall - it's very questions existentielles. We follow Fukazawa down a linear path, with new chapters sometimes jumping forward several months. Nothing disrupts this simple passage of time; expect none of the deliberately clashing visual elements of Asano's art in Punpun, or the pudding-sculpted cartoon bodies of Dededede, its whimsical alien technologies molded digitally from household objects. Not since A Girl on the Shore has Asano pared himself down to such realist fundamentals: well-defined characters standing against drawn-over digital photos. At times there are small deviations; the wallpaper in a certain love hotel becomes very fuzzy and obviously 'digital', creating a slightly unreal zone. Or, all of the sex workers are caricatured to a greater degree than the other characters - sometimes for the purposes of cruel humor, but also to emphasize the enormous cat-like eyes of the woman who's captivated Fukazawa: eyes like those of his actual cat, ailing and beloved, who represents the decaying domesticity between Fukazawa and his wife.

Perhaps we are seeing the sex workers through Fukazawa's eyes - but, really that's how we're seeing everything, isn't it? Unlike any other Asano book in translation, this is firmly the story of an isolated male character, with every supporting character acting as a referendum on him. And he is a fucking asshole! Asano does not apparently want there to be any mistakes in that regard, because he has characters occasionally tell Fukazawa that he is an asshole, and furthermore has a character come out at the end of the book to summarize this point of view, but -- but! -- Asano also does not allow our attention to deviate from him; he does not undercut Fukazawa's primacy in this, the story of his life. He is allowed every justification. At times, Asano seems to be poking at the illiberal tendencies of seinen magazine readers who might sympathize with a male character, or Inio Asano readers who will sympathize with a character so similar to this artist who, if you are my age, you have followed for most of your adult life - following a particularly harrowing scene of domestic violence, Fukazawa remarks: "It's fine. I'm a manga artist, after all. Readers don't care what kind of person I am."

It's a type of spectacle - very 'constructed'. It's not really nuanced; more throwing the contradictions of life against each other, hard. At times, the book reminded me of a greentext post on 4chan, where the writer details a cringeworthy vignette from their life so that readers can enter their headspace - of being approached, say, by somebody who really likes and admires you, and watching them become nervous and embarrassing as they pour out how much you mean to them, and feeling nothing, absolutely fucking nothing, because your mind has dictated to you the absolute artificiality of everything upon which that praise balances, and you cannot, cannot, cannot respond. At other times, I was reminded of Asano's Nijigahara Holograph, in that Asano ramps up the density of baleful events as the story progresses. In that earlier book, a bomb eventually exploded under Asano's style, causing time itself to come unstuck from the glowing hot memory of awful transgressions; now, Asano is content to find new ways to tighten the vice as scenes progress. At one point, Fukazawa meets with a studio assistant, with whom he has had difficulties; at first she seems friendly and contrite, but it gradually becomes obvious that she is only acting this way because Fukazawa, as a senior (and a man), could have her labeled difficult as a talent (and a woman), ruining her future job prospects in this tidy industry.

Through such variations, Asano demonstrates a careful understanding of professional and social pitfalls, and verily sends his damned avatar tumbling down every one. Fukazawa may resent the popularity of his wife’s josei artist charge -- who seems somewhat closely modeled off a real, published-in-English mangaka -- but the small hints Asano drops of her ability to balance work and family while retaining some degree of passion for her art stand in sharp contrast to his gloomy, deadened avatar, who most often seems to focus his ire on women; book sales are his measure as a man.

North American readers may be tempted to compare all of this to a certain lineage of 'alternative' comics, and its long history of revelatory and uneasy personal narratives. Or, if you are the type of person to read the essays in the back of vintage manga translations, you might be thinking this is a shishōsetsu comic, in the manner of recent fictionalized confessional translations like Shinichi Abe's That Miyoko Asagaya Feeling (Black Hook Press, 2019) or Yoshiharu Tsuge's The Man Without Talent (New York Review Comics, 2019). However, I think there is a specific context here to keep in mind. In a discussion from a few years ago with the cartoonist Remy Boydell, Asano was asked about his interest in comics from Garo, the magazine most readily associated with artists like Abe and Tsuge. Asano has cited Tsuge in the past as a great influence on his visual style, but to Boydell he drew a sharp distinction between his work and those of Garo contributors: "that kind of thing didn’t sell well at all." Asano means this as proof of those works' inaccessibility, and, in understanding this correlation between sales and access, we must realize that Asano works his trade in the contemporary commercial sphere, and -- contra the works of Abe and Tsuge -- the story of Downfall is set amidst the angst of an urban professional in that setting.

In his 1997 book Manga Zombie (revised for online, 2007-08, as translated by John Gallagher), the critic Takeo Udagawa characterized the explosive success of Weekly Shōnen Jump in the 1980s as a sea change in Japanese comics - the codification of manga as a commercial product, its financial reliability premised on artists locked into agreements to produce for one publisher and then put into direct and furious market competition with each other via reader surveys. Fukazawa is a seinen artist, addressing a not-as-young-as-shōnen crowd, but this is nonetheless the world in which he exists. It is certainly possible to make a living in this world - in 2009, the seinen artist Shūhō Satō, then under contract with Kodansha, reported earnings of 16 million yen on 450 new pages of comics, with an additional 5.7 million yen coming in on 10% royalties from just under 100,000 copies sold of his newest collected book, against 18 million yen in expenses to staff his six-person studio (needed to produce 450 pages in a year); presumably, he also had royalties coming in on older in-print books as well, so he would be earning a bit more than the approximately $34k USD that would otherwise suggest per annum, but it is a little telling that Fukazawa feels such an intense desire to figure out his next big series. "And in exchange for ten years of servitude," the character groans, "I'd managed to get just a couple years of freedom." Which is to say, a couple years where he needn't work, before the money is gone.

Incidentally, going by Satō's figures, his studio assistants were making less than $30k USD per year from him. Asano too hints at this state of affairs through one of Fukazawa's assistants, who delights in attending publisher functions because that means she doesn't have to spend any money on food that night. Some manga may tint scenes like this in the nostalgic glow of days of youthful struggle, chuckled at from the position of later success; the virtue of Asano's unsparing approach is that characterizing this (and everything) as awful is to emphasize that this is bad - that to lose the competition of commercial art is to be consigned to such a standard of living. But Fukazawa cannot imagine another state - and, this is the state in which Asano works too.

There is an idyll of sorts at the center of Downfall, which finds Fukazawa on a trip out to the sticks with Chifuyu, the young sex worker who fascinates him. Fukazawa comes to imagine that they have started a family - his various sexual frustrations are literarily premised on the notion that working on comics has left him too busy to have a family with his wife, which is very pat, and uninteresting in isolation. But, gradually, Asano draws a parallel between these two workers: they both sought freedom through their work, but Chifuyu is rapidly becoming used to the money from sex work, just as Fukazawa is now struggling to put together a longform work for which he feels no passion, which he will be lashed to for the better part of a decade, all to survive, to work hard hours to beat the other guy with no time for children. Later, in one of his myriad doubled-over fits of melodramatic despair, Fukazawa admits: "I should've told Chifuyu that freedom is a means and shouldn't be the goal."

In a flashback to years before, we see the young, blonde Fukazawa raging against the artistic conservatism of his school peers, spilling out his ambitions. Yet this ambition is his failure as a human being: the rage that devours everything to fuel its core of dissatisfaction. Asano is too observant to suggest that Fukazawa was made into a monster by the work of commercial manga. Rather, his is a personality that is utterly compatible with the corporate demands of this populist fare; it is the battery to his solipsism. What are the classic values of Shōnen Jump? Yūjō, Doryoku, Shōri - Friendship, Effort, Victory. How many manga have you read where the the heroes give it their all to become the best, and even if they don't succeed they learn what's really precious in life? As within, so without: this ideology is the means to attract the ambitious, and encourage them to blow themselves apart. Downfall insists, yes, that Fukazawa is a monster, but be encouraged not to look so closely in his eyes. You'll miss the house of pain around him.