Adam Buttrick was born and raised in the Midwest, but you wouldn’t know it from his comics. They feel universal, otherworldly, or more precisely, untraceable. Buttrick’s line-work and pacing evoke Eurocomics and manga. His character design would fit in snugly with mid-century American newspaper strips by Mort Walker, Johnny Hart, and Mell Lazarus. The narratives that fill his comics are occupied with duality; contentment and contention run rampant on the pages, both familiar and alien. All of this makes the reader feel like they are watching some kind of existential-anxiety-inspired Saturday morning cartoon.

Buttrick is a 31-year-old Michigan native who for the past three years has made his home in Columbus, Ohio. He is married and studied Japanese and history in college. He has been drawing comics “in one form or another since childhood,” but says that he didn’t become serious about it until 2009, when he first attended, and was inspired by, the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. In just a few short years, he has garnered tremendous praise and appreciation: a “Notable Comics” recognition in The Best American Comics 2014, an Igantz Award nomination, a 17-page spread in The Best American Comics 2015, and an invitation to contribute in the next installment of Kramers Ergot.

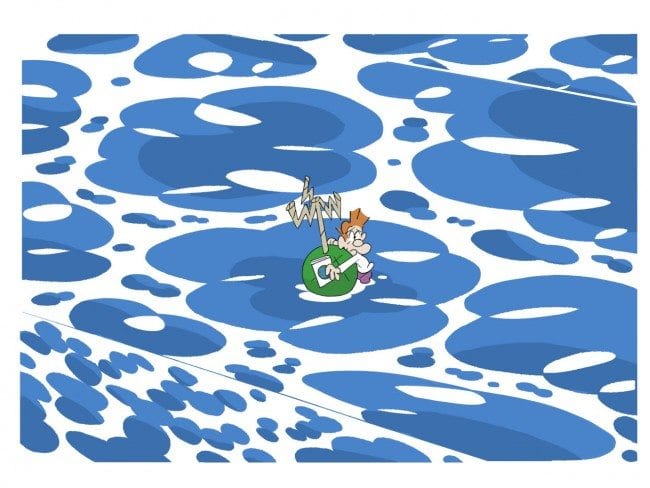

Buttrick’s body of work consists of a handful of short comics on the edges of abstract and lyrical. Buttrick doesn’t go into creating new work with those qualities in mind. “If my comics are referred to as either of those things," he says, "I would guess it’s because of tension between the way I draw and the way the stories are structured.” These are wide-open narratives without a set beginning, middle, or end. His unnamed, big-nosed, and flop-sweat-filled characters are frantically searching for something. Entering and exiting in media res, there is always an inefficient pursuit that results in an examination of identity that goes way past the last flip of a page — nothing is ever solved and no one is ever found, metaphorically or otherwise. Buttrick adds that his worlds and characters “can react against the narratives imposed on them, and possibly should if we value autonomy.”

If Buttrick’s characters are determined to do anything as they anxiously forage around foreign lands and creatures, it’s to find some piece of mind and meaning in the abstract. Relationships and insecurity, perceptions and judgments of others, and goals and occupations, like the conflict seen in Turnip’s Lost Work, are all hang-ups the characters struggle with or, in some cases, run away from. “Nothing closed is worth our time,” Buttrick writes in The Best American Comics 2015, and this ought to be his artist's statement. That means, as readers, we’re never exactly sure if his individuals triumph or succumb to their broad spectrum of obstacles. Sometimes, both frustratingly and true to life, we’re not even given clues. Sammy Harkham, the editor of Kramers Ergot, says one of the narrative strengths of Buttrick’s comics is that “you don’t have all the puzzle pieces, there is no clear theme he wants to impart didactically.”

The vast narratives in Buttrick’s comics also coincide with his incalculable world building. The places he plops his characters, in Buttrick’s words, are “usually the contortions of a character’s perceptions, just like places are in everyday life.” This spatial insecurity leads the reader to believe that everyone is one step away from spiraling into an infinite abyss, especially as they become more unhinged. Stray islands are roped up to prevent them from floating off into the gutters, wooden planks serve as rickety bridges, and walls are unreliable borders. Everything feels as if it will fall apart as soon as the character leaves the scene.

Many comic creators today look to film for inspiration and direction, but, with the ad hoc temporariness of Buttrick’s settings, it appears his surroundings are more fit for a stage. Buttrick agrees, saying “the implicit abstractions of theater are closer to that of comics for me than any other medium.” Some of the locations, like those in Love Understood, feel like they might be found during a back-lot tour of an unstable set. The fact that characters routinely walk, float, and hover give you the sense that rules of physics don’t apply. Risograph printing is used to its full effect in Buttrick’s comics by creating hazy backgrounds of blues and blacks that give each story the shared feeling of treading through an immense empty space. Buttrick claims that he is striving for “an almost impossible openness around the edges [of the page].” Due to the volatile theater-like sets, the characters never get their footing and, in turn, neither do we.

The dichotomy between confusion and comfort are also employed in the way Buttrick sets up and paces his comics. He says that people often “mistake verisimilitude or specificity for honestly, never allowing the reader to imagine something more true about a work.” These are stories without a sense of completion — no prequels, sequels, and certainly no happily-ever-afters. The fluidity of Buttrick’s line and economy of language can make for breezy reads, but the true reward comes from returning to each page or panel and embracing Buttrick’s prodigious duality. Misliving Amended features two characters switching places, but we’re never sure if they are reflections of each other on separate planes or even if they are aware of each other at all. When recalling the moment Buttrick turned in his pages for Kramers Ergot, Sammy Harkham says, “I would be lying if I didn’t initially think the pages were out of order. But it’s intriguing enough to the reader that they will go back and re-read it, and re-read it again.” These clashes of conclusiveness and bewildering destruction of time make Buttrick’s work so fascinating and challenging.

The ability to create comics that are both aspacial and atemporal leads to Buttrick’s greatest strength: subversion. This is not the Johnny Ryan/S. Clay Wilson in-your-face agitation that is the commonplace, albeit lazy, classification of comics rebellion. No, Buttrick’s work is true mind- and medium-altering transgression. In a recent TCJ interview, Jonathan Lethem, the editor of The Best American Comics 2015, remarked, “I’m so excited that something like Adam Buttrick’s work exists. It’s so familiar and so dislocating at the same time. It builds on everything I understand comics to be, but it just seems to be so free in its relation to the definition.” Adam Buttrick’s comics are free in the sense that they force the reader to reconsider the stability of setting and instincts of closure. So free is his sense of style and design, you must reassemble your own preconceived notions of alt comics as Buttrick combines Peyo with poetry, disquiet with Doraemon. So free are his metaphysical plot lines and unique take on the quest for individuality that it requires an almost immediate revisit. By manipulating narrative, time, and space, Buttrick is manipulating the medium itself.