Reprinted from The Comics Journal #139 (December 1990).

In some respects, Aline Kominsky-Crumb epitomizes the underground spirit. You want cruddy-looking, scrawled drawings? You want painfully honest self-revelations? Well, by God, from her very first strip onward (1972’s “Goldie, a Neurotic Woman”), Aline’s got it all. And while her art has gained in maturity and complexity since then, it has never renounced its essential cruddiness — or its scathing honesty.

This approach has proven to be a bit of a double-edged sword. Aline’s work enrages her many detractors partly because its rough surface is so effective at masking her wit, skill, and intelligence. If you let down your guard, it’s easy to confuse Aline the artist with her often buffoonish and overbearing cartoon alter-ego “The Bunch.” Aline dares people to think the worst of her — and because her execution appears so guileless, they often do. Small wonder even her most avid fans often admit that their initial reaction to her work was one of revulsion. But the fact remains: any cartoonist who has ever sat down and deliberately scrawled out an artfully ugly drawing, who has dared to be stingingly, nakedly candid in an autobiographical story, owes her a tremendous debt.

Aline has just ended a three-year tenure as editor of Weirdo (founded by her husband You-Know-Who), which will, if there is any justice in this world, eventually be acknowledged as one of the crucial comics of the '80s. Her paintings — which display her considerable skill and draftsmanship to their full advantage — have been exhibited in many galleries (most recently at the Michael Himovitz Gallery in Sacramento, California), and she’s currently editing an anthology of women cartoonists, Twisted Sisters, to be published by Penguin. Meanwhile, Love That Bunch, Fantagraphics’ collection of her strips, is being released after a world-wide search for a printer who wouldn’t quall at its explicit depictions of blowjobs, masturbation, ass-picking, and self-doubt. All in all, it’s been a good two decades for a neurotic Jewish girl from New York who still draws cruddy.

This interview was conducted in early 1989 by Peter Bagge at R. Crumb’s studio in Winters, California. Bagge’s wife Joanne was also present, as were Aline’s husband Robert and their 9-year-old daughter Sophie.

— The Editor

All images from Love That Bunch ©1990 Aline Kominsky-Crumb

FRENCH KNOCKOFF

PETER BAGGE: Ay-LEEN is the correct way to pronounce your name? There seems to be a lot of confusion.

ALINE KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. In France it’s a real common name.

BAGGE: And what’s “Ricky”? Where did Ricky come from?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: My real name. There was a clothing store in Far Rockaway called Aline Ricky. They had French knockoffs. Knockoffs are copies of French fashions.

BAGGE: So you were named after a clothing store?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: A fake French clothes store. No wonder I’m a Francophile and I have pretensions. [Laughter.] I love pâté and shoes.

BAGGE: Was “Goldie” another nickname that you had?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. My maiden name was Goldsmith.

BAGGE: So you were born Aline Ricky Goldsmith and your first husband’s name was Kominsky?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah.

BAGGE: So when you were divorced, why did you keep the name Kominsky?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I liked it better. Kominsky’s more ethnic-sounding.

PSYCHOTIC CHILDHOOD

BAGGE: First I figured I’d just ask you about when you were born and where and all of that.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I was born August 1, 1948 in Long Beach, Long Island. I lived in Far Rockaway [in Queens] for my first four years, and then we moved to Woodmere where I spent the rest of my childhood growing up. Robert calls it “Yidmere.” It’s right next to Cedarhurst where my mother still lives.

BAGGE: That’s what you refer to as “Hebrewhurst” in your comics. How old were you when they brought you there?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: To “Yidmere”? Four, because that was right before kindergarten. They wanted me to go to a good school. They wanted to get me out of Far Rockaway. Puerto Ricans and blacks were starting to move in there.

BAGGE: Would you explain what your early family life was like as briefly as possible? You don’t have to go into detail because once you start talking about your comics, you’ll be sort of going over it again.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: When I was 4, my brother was born. He was definitely a weird kid. He was born with this big birthmark which they had to remove with painful treatments. He became real withdrawn. My parents’ life started really deteriorating by the time we moved to Woodmere because my father was running these different businesses into the ground and losing my grandfather’s money. They bought this real expensive house, and they were living really above their means. They started fighting a lot about money and everything.

BAGGE: Would his finances tend to go up and down, or ...

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Oh, completely up and down. It’s like one day there would be a new yacht, and the next day there would be no food in the fridge.

My mother was spoiled and used to living high — her parents had a lot of money — and my father was irresponsible. They were really young; they got married when they were 19 or something. My mother was 19 when she had me, and my father was 23. They were real immature, reckless and crazy. Horrible psychotics to grow up with.

BAGGE: Was the pace kind of stable when you were little and just got crazier?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: The first four years were pretty stable because we lived right near my [maternal] grandparents’, and I spent almost all my time at my grandparents’ house which was ideal. It was really secure. I remained close to them, but once we moved we weren’t as close. Their house was 45 minutes away instead of being really close by.

We lived in this horrible fancy, ’50s suburban tract that was built on an old golf course. It was bleak. Sterile and cold and unfriendly.

BAGGE: Did you have an artistic inclination when you were a kid?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, but my parents didn’t try to encourage it. I had every lesson available to children, but only to make me into a refined product so that I would marry some rich Jewish dentist and get a house in Great Neck.

Except when I was 8, I really wanted to paint and they let me take painting lessons. This real sincere, idealistic Pratt student turned me on to painting, real painting. I actually did some oil paintings that were good.

From around age 8 to 14 I was real creative and serious about painting and ceramics and pastels. Then I got into boys and totally gave it up.

BAGGE: Were you into technique?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I was into trying to make good painting. I like cubist paintings a lot. I really liked Picasso and Matisse and Cezanne when I was a little kid.

BAGGE: So you went all through grade school in Long Island?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I went to the same school, same friends, everything. All in Woodmere. Very upward-striving, competitive little Jewish monsters.

Then I went to Lawrence High School where five towns came together for junior high. That was the first time I went to school with black kids and Italians, and I was really scared of them. I’d only seen black people as servants before. My first day of junior high school I got stabbed by this black girl with a safety pin. It was my worst nightmare. I was a total little racist.

BAGGE: Was it like that all through the rest of high school? The mixed races?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It was mixed, but I was in an academic, college-bound track. By the time I got to high school, the black kids were in the vocational, business end of the school, like beauty culture. We were in the other wing of the school, and we had different lunch periods.

BAGGE: So the school became segregated within itself.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Completely. In my high school yearbook there were all these pictures of people I didn’t know.

BAGGE: All the white kids must’ve been Jewish?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I would say above 75 percent were Jewish. When I graduated and after I moved out West, I couldn’t believe there were so many blond-haired, blue-eyed people in the world. I had such a warped view of reality. I was brought up so ethnocentrically.

BAGGE: Except for Peggy Lipton. [Mod Squad and Twin Peaks actress Peggy Lipton was a classmate of Aline’s.]

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. Peggy Lipton. The one token goddess Jew. She was like a genetic quirk.

BAGGE: A freak of nature … Your father died when you were in high school?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Out of high school. I was 19 when he died. I was already living on the Lower East Side.

BAGGE: Did that change your family situation? Was your mother working before then?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: My mother started working when I was about 10. She started her own career. She went to Weight Watchers; she got thin. She became an emancipated woman. I don’t think my parents had that much to do with each other from that point on. My mother probably would have divorced him if he hadn’t died.

When he died, she refused ever to go back into the house where I grew up. She made me go back in there and sell up all the stuff and sell the house. She bought a condo and never went back there. We were never allowed to talk about my father or anything that happened in my childhood. She remarried a year later. If you try to bring up something from my childhood, even now, she changes the subject.

BAGGE: So she doesn’t have fond memories of that era.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I think she’s happy now. She was 38 when that happened. She’s had the second half of her life with no kids and a nice husband and great job, a nice condo. That’s really what she wanted.

She doesn’t realize that we had this psychotic childhood. She denies that she put us through hell. We have no point of reference. There’s no use saying anything. My brother’s too crazy to talk to about it. I think that’s why I’ve done so much writing about it. It’s my only outlet.

BAGGE: So you talked about it with strangers, all your readers.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, I had to get it out. I never went through therapy. I foist it on the world whether they like it or not [laughing].

BAGGE: They don’t have to buy it.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: They don’t buy it!

BAGGE: So you went to an upstate college?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: First I went to the state university at New Paltz where I got pregnant the first week. I ran away a few months later. I climbed out the dorm window.

BAGGE: So you didn’t even make it through a whole semester there?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It was on a quarter system. I made it for one quarter. I made it to Thanksgiving vacation.

BAGGE: Does your mother know all about this?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No, she never knew — and still does not know — that I had a baby. I ran away and found this apartment on the Lower East Side on 3rd Street.

BAGGE: Did she think you were still in New Paltz?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: She just thought I’d become a hippie like everybody else. She was worried, but there was nothing she could do about it.

My father was obsessed with finding out what I was really doing at the time, so he tracked me down to the Lower East Side. Right before I was about to have the baby, he came to my apartment. I looked through the peephole, and he was there. I flipped out. I didn’t answer the door.

I went to this Jewish adoption agency early in the pregnancy and they found a family for it. They were giving me money, and they made me see a psychiatrist every week so that they could ascertain if I was sane when I signed the adoption papers.

I called my psychiatrist up and I said, “My father just came and I don’t know what to do.” She said she would call him and have us meet in her office. He came and saw me pregnant. He was upset, crying and everything. Then the psychiatrist said, “Well, don’t you think you should tell your wife now so she could go home?” He said, “No! Don’t tell her. She’d go nuts. She’d never let you forget that you gave up her grandchild.” I never told her. Two months after I had the baby he died, so the secret died with him.

BAGGE: Were you close to your dad at all?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. He was a fucked-up person with all kinds of mixed emotions and wasn’t really in touch with what was going on. He was erratic. Sometimes he was nice to me; sometimes he was horrible.

In the last six months of his life, he was really different toward me. I think he respected me for [giving up the baby] in some weird way. He didn’t try to control me or tell me what to do after that.

BAGGE: So after you had the baby, you were living in the Lower East Side, and then you started going to Cooper Union [an old, established art school in NYC]?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I was going to school there and working on Wall Street.

BAGGE: Oh, really? Doing what?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Some clerical stuff. I tried to work at nights and crazy hours. Wall Street was booming then; they hired anybody. You could go to work wearing any outfit you wanted. I had a whole bunch of friends at Merrill Lynch. We’d just go at night, get stoned, and do some ridiculous job.

BAGGE: Were you doing comics at all then?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. I was painting and drawing. I always kept these notebooks of humorous drawings of people on the bus. I used to draw mean drawings of people in my high school classes all the time, passing them to other people to get them in trouble. I always drew caricatures of people. I always kept notebooks of funny-looking people.

BAGGE: Did they have captions and word balloons in them?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Sounds, like fart sounds. Really stupid stuff, low-brow humor.

BAGGE: So you went to Cooper Union just for a couple of semesters?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, I went there for a year until I totally hated art. All the people there were driven. They were really mean and competitive.

BAGGE: Everybody I know that went to Cooper Union didn’t have a talented bone in their body. That’s a free school, isn’t it, if you get accepted? I always wondered how they got into this free school.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I don’t know. They give you this long, grueling entrance exam, and if you do well on it, you get in, I guess.

BAGGE: So when you left college, you stayed in New York City for a while?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I stayed there, and then I met my first husband [Carl Kominsky]. He wanted to go out west to Arizona, but he’d got busted for selling dope and had a year’s probation. When the year was up, he wanted to go back. He really talked up Tucson; he said it was really nice.

BAGGE: Was he a native New Yorker?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: He was from Long Island, too.

BAGGE: Oh, yeah? Just another New York Jew boy?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: A nice Jewish boy. So right after my father died Carl was going to leave. I didn’t want to get stuck in New York because my mother wanted me to move in with her; she wanted me to get an apartment in the city or something so we could be swingers together [Uproarious laughter.] My worst nightmare. She wanted to force me to be her best friend. So I married this guy instead.

BAGGE: You married the guy to get away from your mom?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah.

BAGGE: Was your brother still living with her then?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No, he was in a bad boys prep school in upstate New York. Peekskill, I think. [Bagge’s hometown.]

BAGGE: Was it like a pseudo-military academy? I remember that place. Poor guy!

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: [Laughs.] That’s where he got into heavy narcotics. All the kids were into drugs up there really heavy. He went from stealing my mother’s downers to taking heroin and stuff. He was stoned all the time.

I went up there to get him when my father died. No one had even told him my father was sick. I just went up there and said, “Oh, our father’s dead.” He was completely out of it. He was just so stoned.

Later when he was kicking heroin, trying to get therapy and get better, he was so angry. He didn’t even know his father — he was stoned all through high school — and then Dad died. It was so troubling to him that he’d never dealt with any of it. He has a lot of anger and resentment in him over this.

HIPPIE HEAVEN

BAGGE: So you moved to Arizona with your husband?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven, even though he was sort of a shmucky Jewish guy. He used to leave his dirty underwear on the living room floor for me to pick up. If I broke the yolk on his eggs over easy, he used to fling them at the wall and things like that.

Tucson was a pretty small town then. It was the late ’60s. It was beautiful. I loved it there. I took a lot of peyote and other drugs.

BAGGE: Hippie heaven.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Hippie heaven. I went to art school there, and it was really fun. I had these nice, cute art teachers that were real encouraging. I got to paint watercolors in the desert. I had a little motorcycle. It was beautiful weather. Cheap rent, I lived in a really great adobe house for 50 bucks a month. It was just heaven.

BAGGE: Did you stay together with your husband for very long?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Three years. I graduated school there, and then after that I left him and ran off with a cowboy for six months. [Bagge laughs.] I lived with this guy and his two brothers and their father in this small town in Arizona out in the middle of nowhere.

BAGGE: You’re kidding. For six months you lived with these cowboys? It was like you moved in with Bonanza.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: More like The Last Picture Show. These guys were crazy. They took a lot of psychedelic drugs. The guy that I lived with was killed in a gunfight after I left, a love triangle. Then his brother killed the guy who killed him, and he went to prison for life. And then the father died of a heart attack. This all happened within a two-month period.

BAGGE: So you were a real-life Jewish cowgirl, just like in that old strip Crumb did.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: That’s right. I was amazed when I saw that comic.

BAGGE: You would actually ride around on horseback, shooting lizards and stuff like that?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Uh-huh. While on drugs.

BAGGE: Were you enjoying yourself?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I loved it! But it wasn’t leading anywhere. I had to get out of that life at a certain point. The guy that I was involved with moved to San Francisco a short while after I did. He was hanging out with my brother, dealing drugs and getting into all sorts of trouble.

BAGGE: Did he go there because of you?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I didn’t think so—as far as I was concerned there was nothing between us anymore — until one night when he walked into my room while Crumb was with me and pointed a gun at Robert’s head [laughs].

BAGGE: So why didn’t he kill Crumb? If it was true love he would have!

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well gee, he wasn’t that evil a guy! The guy was really trying to transcend that crazy, violent lifestyle that he grew up in but he just couldn’t do it. He just couldn’t stay out of trouble for very long.

BAGGE: And then he wound up getting wasted, right?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Right. Just one more thing for me to feel guilty about. I felt like I toyed with this primitive person for my own pleasure and then threw him back to die. I tried to help him, but it was beyond me, obviously. Anyhow, my brother told me later that the gun wasn’t loaded.

BAGGE: Crumb says it was. He also doesn’t think this story is very funny.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, well … heh heh. [Bagge laughs his head off.]

BAGGE: So you moved to San Francisco partly to get away from this guy?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Mainly because of the underground comix scene. It was around this time that I had discovered underground comix. I had met Kim Deitch and Spain Rodriguez who were visiting Arizona around that time, and they influenced the move, too.

BAGGE: So you started reading undergrounds in Arizona?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, I started buying them. I saw Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary by Justin Green. That was a comic that really moved me to draw.

When I saw what he had done with this autobiographical, straightforward, crazy story about everything that happened to him, I started approaching it in this straight-forward way and it was really satisfying to me. I had this revelation. I thought, “I could do that. That’s what I should do.” The light bulb went off.

BAGGE: Were a lot of other comix inspiring to you?

KOMlNSKY-CRUMB: They were less accessible to me. People could really draw good, and they were more traditional. Robert’s comix were obviously influenced by some older style, and he was so accomplished. They were something I could never aspire to, and I still feel that way. It’s like some other realm.

BAGGE: Were you familiar with Deitch’s and Spain’s work at the time you met them?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, and I liked their work, too.

BAGGE: Did they talk you into moving to San Francisco?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. They really gave me a sales pitch to move there, and get into the comix world. It was probably sort of patronizing, but they liked me and wanted me to move there.

BAGGE: You didn’t mind moving away from Arizona?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I did. It was like cutting my umbilical cord. It was really hard for me to leave. That’s partially why I left.

BAGGE: I got the impression from your comics that you burnt all your bridges in Arizona. That you sort of went wild there and wanted to make a clean start of it again.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: There was that aspect to it, but that’s an exaggeration. I was accepted to graduate school, and I got a teacher assistantship, at University of Arizona.

BAGGE: It was almost strictly the cartooning that made you want to try San Francisco?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No, it was the fact that I had slept with every art teacher that I had.

BAGGE: And that made things a little awkward?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I mean who wants to sleep with the same stupid art teachers for the rest of their life?

This is the more idealistic side, but I felt that it was a situation where I probably wouldn’t grow much as a person. It was very womblike and a very incestuous art scene there. I would probably have found some niche for myself, but I wouldn’t necessarily have found anything really fulfilling. It would have been stultifying in a certain way which has proved true when I see what people are doing there now. It was a good decision to leave. It was a very seductive place because it was cheap and easy to live there, and I had my whole little thing worked out. Moving to San Francisco was almost like moving back to New York to me. It was much more high pressure and big city. You needed money and a job and all that.

BAGGE: Was that the first thing you had to do when you got to San Francisco, find a job?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I found a job at Glide Memorial Church Publication Company. They published goody-goody left-wing books, like lesbian and gay literature and Dan O’Neill’s Odd Bodkins books. I was just the bookkeeper.

BAGGE: That’s how you met Dan O’Neill?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, he used to come in there and always wanted advances. He used to hang out in my office for hours and hours hitting them up for lunch or beer money. I’d give him a dollar out of my own purse. I’d feel so sorry for him. He was also coming on to me at the time.

BAGGE: Was he the first cartoonist you got to know once you got to San Francisco?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, no. I hung around with Spain and Simon Deitch. By the time I moved to San Francisco Kim [Deitch] had already moved up to Oregon with Sally Cruikshank.

BAGGE: You met all the cartoonists pretty fast, didn’t you?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, because I knew Spain and Kim and Simon [Deitch]. It was a pretty tight scene. Then I went to the Wimmen’s Comix meetings where I ended up meeting Trina [Robbins] and Sharon Rudahl (I think), and Pat Moodian and Larry Todd, who was going out with her. Then I met Dan O’Neill and all the Air Pirates. I went out with a lot of different guys.

BAGGE: You went out with a lot of cartoonists?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I went out with Gary Hallgren and Willie Murphy, Dan O’Neill, Kim Deitch, Spain. Everybody. Too many.

BAGGE: An embarrassing amount? [Laughter] Is that why you’re rolling your eyes?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I could brag about it or be embarrassed about it. Take your pick. I won’t tell you about the more despicable ones. I was a wild 23-year-old. But when I met Robert, it was true love.

BAGGE: Up until that point, were you like a cartoonist groupie?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I can see how it might seem that way, but it was such an open scene at that time, and everybody was running around. Everything was very loose. Besides, I don’t think I was that adoring or awestruck by these guys.

BAGGE: So you didn’t make plaster moldings of cartoonists’ erections? Do you remember that ad in the Whole Earth Catalog? [The ad showed a plaster cast of Jimi Hendrix’ penis alongside the much smaller phalluses of his white band members.]

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I suppose I could always go back and do ’em.

BAGGE: You should! Then you could sell them at comic conventions.

KOMINSKY-CUMB: Some of them are dead ...

BAGGE: Those are the ones that would really be worth money. You missed a golden opportunity.

KOMINISKY-CRUMB: So it wouldn’t be worth pursuing at this point … Besides, Crumb’s would be the biggest [giggles].

BAGGE: Oh yeah? Crumb’s the Jimi Hendrix of underground comix, huh?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: That’s right. Why do you think I married him [laughs].

BAGGE: I figured there had to be some secret reason. Now the truth is out.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Seriously though, Crumb was the best. He’s a very passionate lover.

BAGGE: So you drew cartoons in earnest at this point? Were you really concentrating on it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I was doing this job and then drawing comics, and I really became driven to publish my work. I started reading undergrounds seriously and looking at people’s work, the closest I ever came to studying the art form.

BAGGE: So this was around 1972, right?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Late ’71.

LADIES FIRST

BAGGE: There was sort of a women’s comix collective or something. Is that how you described it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. By ’71 it was just getting together. I came in pretty much at the beginning. They were having meetings to try and publish. They had done It Ain’t Me, Babe before that, I think.

BAGGE: Was Trina in charge of this women’s collective?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Absolutely. Nothing’s changed in that regard.

BAGGE: Was there subject matter that you wanted to deal with because you were women or did the collective exist because you felt women were still a little on the outs in this cartooning field?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: The comic had some women’s issues in it, but it was pretty psychedelic and real crazy stuff. For me personally, I just wanted to get my own work published. I wasn’t very skilled, and this was a beginning group of artists. I didn’t care if it was men or women. They accepted me. I felt like nobody was skilled so I didn’t feel stupid. I certainly wasn’t going to get in Zap Comix. For me, it was less intimidating that it was women.

I guess Trina had experienced exclusion from the men, so she felt very strongly about creating a separate vehicle for women. I hadn’t experienced that. The men I knew were real nice to me, like Dan O’Neill, Willy Murphy, and the Air Pirates. They were very encouraging and supportive.

BAGGE: Did you submit your work anywhere previous to Wimmen’s Comix?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It wasn’t developed enough to submit to anything.

BAGGE: So this was the first time you were ever published. I hadn’t read this first issue of Wimmen’s Comix until recently. I was pretty impressed with it because, even in a legal sense, it seems like women were more of an oppressed minority, with abortion being illegal, so the subject matter dealt with grimmer issues like illegal abortions.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I was a victim of that myself. I had a baby. I couldn’t get an abortion.

BAGGE: So there’s this real grimness to it, but at the same time it seemed like they dealt with these issue in the way that you still do with your comics. It didn’t have the sanctimonious tone that it seemed to develop later on. It’s horrible, but they dealt with issues like illegal abortion in a sort of detached, joking manner.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: A bit more forthright. Yeah. It hadn’t gotten convoluted and twisted yet.

BAGGE: Was it fun? Was it inspiring for you to work together?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It was really fun because it was the first time in my life I’d ever been involved with a group of women artists. In art school I had all these male teachers who were very domineering, handsome, chauvinistic. That was fun in its own way because it was all sex and perversion and power games, but it wasn’t very good for my artwork. This was the main reason that I left there. This was like a group of absolutely equal people, and it was really exuberant. There was a lot of energy. It was a good period for me. I was happy to meet those women and be in that book. I was so excited to get my story published. It wasn’t that long after I came here that it came out.

BAGGE: This first story that you had in print — this “Goldie” story — seems like it’s a little capsule of everything that you’re going to deal with in your comics from then on. Did the other women recognize and appreciate the blatant honesty that you showed in this strip?

KOMIMSKY-CRUMB: No. Right from the beginning I got a lot of flak from everyone for being so primitive and self-deprecating. Women like Trina were influenced by traditional comics. They had images of women being glamorous and heroic. I didn’t have that background.

I didn’t have any control over it. My cartooning was unconscious and still is. I didn’t contrive or plot to do something in a certain way. It was the only way I was capable of doing it. I couldn’t even make up a character. I didn’t know how. I wasn’t trying to be subversive or do something different or make some statement.

BAGGE: When it came out, once it was sort of seen by people outside of the women you were working with, did you get a strange reaction? Did you get more flak from the people who read it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Some people thought I had a good sense of humor and was a good writer. Dan O’Neill liked my work. Those guys thought I really had something to say, but they tried to get me to develop one of those old-fashioned drawing styles.

BAGGE: So most of the people thought the style you were working in was a big detriment. Was there anybody that thought that your style worked?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: [Laughs.] Not that I’m aware of. Diane Noomin liked it.

BAGGE: Eventually I suppose there were others who felt that the way you drew sort of suited the purpose.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, but that was slow in coming. The thing is, I could have made my comics more appealing or attractive looking, but I just didn’t want to.

BAGGE: Yeah, sure!

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I’m serious!

BAGGE: I was being sarcastic.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I’m being honest. I could make it more arty — cute line drawings with lots of patterns and less tortured hatching — if I worked on it.

BAGGE: I was going to ask you a bunch of mean questions about your drawing style later.

You still contribute to Wimmen’s Comix off and on, but was it awkward staying on with that comic book? Did it stay as a cohesive group?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. There was fighting right from the beginning.

BAGGE: So you started creating a distance after the first issue.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, I was rejected. I can’t remember what issue it was. They rejected my work, telling me that I hadn’t had a significant raise in consciousness from my story in the previous issue.

It was actually the fact that I was involved with Robert Crumb that was the issue. He was the enemy. I was an Uncle Tom.

BAGGE: Are women still held back professionally in this business? For example, there is still something called Wimmen’s Comix.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I think Wimmen’s Comix is an anachronism at this point. I first got involved when the Zap thing was happening. I think it was a bit too macho and exclusive. It was like a boy’s club: “No Girls Allowed.” That’s why I think Wimmen’s Comix was important then. Those guys were very slick, skillful artists and very macho about it. It was intimidating.

Some women would not have tried drawing comics if a women’s comic didn’t exist. Now I don’t see that kind of prejudice against women. If you’re a good cartoonist, you’ll get your work published. I can’t see that Krystine Kryttre and Carol Tyler have been held back at all by being women. Or Lynda Barry.

BAGGE: Do you see much of a difference between women’s and men’s comics?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: There’s so many crazy, off-the-wall people doing artwork that I don’t see that as being a major distinction anymore.

BAGGE: I saw a book called El Perfecto. What is the story about that?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I edited that. My roommate, Betsy, had become involved with Timothy Leary, getting him out of jail. His girlfriend Joanna Harper had a whole foundation trying to get him out and this whole big “Free Tim Leary” thing. I hated Leary, but my roommate was really into it. I hated Leary’s girlfriend, too, but they talked me into raising money for him. So I decided to do this benefit comic; I got everyone to donate the artwork. I gave Leary’s girlfriend the money, and that bitch bought a stereo system with it.

BAGGE: So you did all this free work for Tim Leary who you hated?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I hate him now. At the time, I was sort of convinced that it was worth it. I was peripherally involved, sort of sucked into this. I really liked my roommate a lot, and I respected her. She was older than me.

BAGGE: Even though she was a sucker for Tim Leary?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I really looked up to her. But I hated Leary so much after that. He put down underground comix in a real snotty way later when he was Mr. Yuppie. He said they were utterly negative. He only liked beautiful people.

BAGGE: Oh, I see. He was speaking almost directly to you and Robert. So you did a benefit and it all went for somebody’s stereo. [Laughter.] It’s not a bad comic book. You had some pretty good artists contributing.

What I liked about the magazine is that it dealt with psychedelic drugs, but instead of the artwork being a result of drugs, it dealt with taking them. Usually when you think of LSD in the comics, you wind up with this “What’s it all mean?” Rick Griffin-inspired work.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, I asked the artists to do true-life stories. I tried to guide people away from that, like that story Robert did about throwing up on his wife’s face.

BAGGE: Yeah, that was pretty good.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: That original art was almost destroyed as I was bringing my book down to the publisher. The car caught on fire. We just escaped with our lives and the artwork. The whole car went up in flames one minute after we got out of it.

HONEYBUNCH

BAGGE: Were you interested in meeting Crumb before you knew him.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah.

BAGGE: Was it because you felt that he was writing about you in his comics?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, I thought he was a good artist. His female characters did resemble me and one even had my name [Honey Bunch Kaminski].

BAGGE: Was it a short while from the time that you moved to San Francisco that you got involved with Crumb?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I was so fucked up that whole time. I can’t even remember accurately the secret liaisons. He was still involved with his wife, Dana, but he was also involved with Kathy Goodell. Then he met me. I tried not to get to involved with him, because obviously his life was a mess, but I was really attracted to him.

BAGGE: So in spite of yourself, you pursued him?

KOMIMSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, but I was involved with other guys also. What happened was that Ken Weaver [founding member of The Fugs, writer, and would-be CIA agent] came to live with me and Dana started getting involved with him. Then Ken Weaver and I moved up to the property in the country where Dana lived and Robert sometimes lived.

BAGGE: This was the property in Mendocino that Robert owned?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. There was a house and a cabin. I had a trailer and Ken had a trailer. We all became this little commune at that point.

BAGGE: So you and Robert and Dana and Ken Weaver were all living…

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Up there.

BAGGE: Were other people living up there too?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: People came and went. There were also two kids. Dana had lived with Paul Seidman and had another kid with him [the “Little Adam” from Dirty Laundry #1]. [Seidman] was getting the bum’s rush and Weaver was moving in. Everything was vague and crazy then. No one just broke up and said, “Beat it.” Everybody’s older lovers were still around along with the new ones.

BAGGE: Was that awkward for you, living with Crumb’s wife?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I liked Dana and she liked me. When Robert really started to get involved with me, she started to torture me. It was OK.

She was going out with two other guys. It wasn’t like I was with Robert and they were together. They had already split up. That’s how it seemed to me at the time.

Crumb was still seeing Kathy [Goodell] and he had other girlfriends. I had other boyfriends. That was the time. It was all a mess.

BAGGE: It sounds like a little Peyton Place up in them there hills.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It was hell. Total hell.

BAGGE: Was it miserable truly, or was it interesting?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Both. It was beautiful up there. We took a lot of LSD. We drew. It was both idyllic and hell at the same time.

BAGGE: Did Robert like your comics the first time he saw them?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, he did. I was really nervous. I wouldn’t show it to him. If he’d said something bad, I would’ve been devastated. He seemed to genuinely like it, but I can’t tell. He wanted to sleep with me, so ...

BAGGE: So do you still think he’s just telling you that your stuff is good so he can sleep with you?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. [Laughs.] He’s brainwashed. I think one of the reasons why I was able to keep drawing comics, even though he was so much more accomplished than me, was that he really seemed to like my work and that really gave me a lot of support.

BAGGE: I always get the impression from Crumb that he thinks that the way your artwork looks is just perfect for the content. Did he encourage you the way that these other cartoonists did to adopt an old-fashioned style?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: He just said, “Your work is really funny and unique. You should just do that.” He always thought it was really funny and made it on some level.

He said, “I don’t know why it’s this good, but it is.” That was really an important thing to me. Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman also liked my work a lot, and they were real supportive to me.

BAGGE: Were any of them able to articulate why they liked it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: They responded to this crazy primitive stuff. They really thought the writing was strong and the drawing was expressive.

BAGGE: Even though Crumb’s life was so crazy, he still gave you emotional support.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: He was really an amazingly giving, loving, affectionate person. I was always deprived of that kind of attention before.

BAGGE: How did he get a reputation in those days of being such a self-centered bastard?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: He was real immoral in the sense that he’d go from one to the other. When he was with you, he could really focus completely on you. You seemed like the only important thing in the universe, but he did that with a lot of people. He made me feel really good, but then of course I was jealous because he’d do that with other people, too.

BAGGE: Once you got involved with him personally did you start catching a lot of flak, with him being branded such a racist and a sexist?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. Plus I was dressing to suit his tastes. I was wearing boots and short skirts and catering to his sex fantasies and competing for his attention. I’m sure it was very disgusting for a lot of people to view.

BAGGE: Did you mind? Was dressing for him repulsive to you?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No, it was fun. I liked his attention. I was in love with him.

BAGGE: So you never felt like you were dressing like a clown, like, “Is this worth it?”

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I was under his spell. I wanted to please him. It was really satisfying for me to get approval from him. [Bagge is beside himself.] Isn’t everyone that way with a person that you’re really in love with? Don’t you try to attract the person that you want to attract?

BAGGE: I’m not aware of when a woman’s doing that, but if a guy friend of mine starts going out with a woman and all of a sudden he starts combing his hair like Elvis Presley or something like that, I find that pretty repulsive.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s embarrassing and hard to admit, but I assume that everybody does that. In my case it was so obvious, since his taste in women is well-known. It’s this stereotype that was really absurd.

BAGGE: But he never dressed for the lady according to what he told me. He told me that Janis Joplin used to always tell him, “Why don’t you grow long hair and wear a velvet shirt. Don’t you want to get laid?” He wanted to get laid, but he didn’t modify his appearance at all.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: His appeal to me was his being a goofy absent-minded professor on the outside and a sex-crazed demon within ... and his total focus on me!! Most people can’t devote that much attention to the person they’re with. Very seductive.

BAGGE: But how can you stand being married to the world’s worst sexist, racist, anti-Semite?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: He once asked me if I thought he was an anti-Semite and I said I couldn’t tell because nobody is more appalled by the Jews than I am. [Laughter.] He can’t help but make fun of us since he’s had two Jewish wives, Jewish in-laws, Jewish doctors, lawyers, accountants, his best friend Terry [Zwigoff] is a Jew ... but then, how could you call him an anti-Semite if he’s always surrounded by them?

BAGGE: Nobody can hate a Jew more than another Jew. They seem to give each other very little slack, from what I’ve seen...

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s a disgusting race. [Laughs.] It’s just that Jews are so high-profile, so driven to succeed, so competitive, that’s where all that animosity comes from.

But then there’s the other side of it where we have to stick together and to support Israel no matter what, which is just as crazy … but oy, I’d better not get into that or I’ll get in trouble.

BAGGE: Overall, have you enjoyed the vicarious fame that comes from being Mrs. R. Crumb, or do you sometimes resent it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: At this point neither. At first it was exciting, since it gave me access to certain things, like free trips to Europe, but knowing that it’s all meant for him and not for me definitely took the shine off of it after a while. I’ve since learned to keep it in perspective, not to let it get to me in either way. But I’ll still take advantage of the perks when they come along.

BAGGE: Generally speaking, do you feel overlooked as an artist, at least in comparison to Robert?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: How could I? He’s produced such an amazing body of work, he’s accomplished so much, that I’d never expect to get the same kind of treatment that he receives. I’ll admit that when I see an article on underground cartoonists or women cartoonists and I’m not even mentioned, I’ll feel slighted. In that Ron Mann movie [the 1988 documentary Comic Book Confidential] Weirdo wasn’t even mentioned; that bugs me. Basically the amount of attention I’ve received so far is enough to make me happy. I have no major complaints in that regard.

Also, I think my work is great and I’ll eventually be recognized as the genius that I am!

DIRTY LAUNDRY

BAGGE: Was it while you were living in Mendocino that you guys started doing Dirty Laundry?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: What happened was one of Crumb’s other girlfriends, Frankie Politi, arrived with all of her possessions to move in with him, and I had a total shit fit. She’s just a monster. She was hiding in his cabin with him, and I was fuming in my trailer next door. I was wearing these giant platform shoes. I ran out the door and I fell and broke my foot in six places.

So he threw her out, and I had a big cast on for the rest of the winter. It was raining, and I was going crazy. So just to keep me out of his hair, he said, “Let’s do these two-man comics. I used to do this with my brother when we were kids.” We did that whole first Dirty Laundry, and then I think Keith Green saw it and wanted to publish it. He was Justin’s brother and he was this real sleazy publisher.

BAGGE: When you started doing Dirty Laundry, did you begin to make a long story, or did you doodle it first?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: We just piddled at first, we were just doing it for ourselves. We moved out of Potter Valley to Dixon, where we finished it that summer, and it got published sometime later.

BAGGE: Was it published in another edition first? Because I seem to remember seeing this for the first time around ’77.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I don’t remember. That’s the kind of stuff that I couldn’t care less about. That’s the kind of stuff that doesn’t stay in my head.

BAGGE: When you began to do this story, did you have any idea what you were going to talk about between the two of you, because by the third page you already have Robert climbing all over you, and it shows the two of you having sex?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s real spontaneous. This is not work. This is just having fun. Just feeding off each other. One person does one thing, and the other another thing.

BAGGE: Did you have any reservations about it being in print?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I never think about anything like that.

BAGGE: In the introduction you made a point about being self-conscious of the fact that Crumb’s fans will have a fit.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I thought that, but I liked the idea of being obnoxious and bratty that way because his fans are so repulsively fixated on him. I kind of enjoyed being a slut-brat, an irritant. I generated great hate mail.

BAGGE: That was my next question: how does it feel to be the Yoko Ono of comics?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I like it. I like being the devil girl. Sometimes your enemies define you as well as your friends...

I consider those Dirty Laundry stories to be satirical. I know my life is much more full and whole than that, and I know that my place in Robert’s life isn’t quite like it’s portrayed in those stories.

It’s like this pushy, obnoxious, desperate creature trying to push her way onto the page. I can see that aspect of myself and I like to play it up. It’s important to me to reveal the real repulsive side of me. It’s what people like to think, so I like to feed it to them. It’s funny and it frees people to be themselves.

BAGGE: Was this something that you did as soon as you started doing comics? Even in your own comics you would betray all the worst aspects of yourself.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, but I didn’t think that out. It’s just what came out. It’s what I have to do … like shitting!

BAGGE: And when people did react negatively were you shocked and upset that people were so hostile toward you, or did you find it an inspiration?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It was stimulating to me and shocking at once. I got off on it. Feedback is artistically inspiring. I never expected too much adoration for my work because it’s so uncivilized.

BAGGE: You never had any notion of making a living off your comics?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Not really. To me, art was part of a continuing need to express myself from the time I was a kid. It was just this compulsive need that I think always existed in my life.

TWISTED SISTER

BAGGE: Your next project was Twisted Sisters, a shared title with Diane Noomin.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: That was really fun. We decided to do it together as a project. We were pals. We liked and still like each other’s work. We felt our work was complementary. Neither one of us liked what was going into Wimmen’s Comix that much, at that point. We really didn’t like the Trina influence. I don’t know what you want to call that, this idealized feminism.

BAGGE: You mostly wanted to be more satirical and self-deprecating?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Not wanted to. I just had no choice. This is the way I was and am. This is my world view. I don’t romanticize life, and I don’t think that romanticizing women makes other women feel better. It makes most people feel worse.

BAGGE: Diane Noomin always uses a fictional character, Didi Glitz. It’s like an alter ego for her. On the surface Didi’s a glamour girl, but a glamour girl that’s pretty miserable, that’s not too aware of what’s going on in her life.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, it definitely captures some real truth about herself and a certain type of woman in general.

BAGGE: Did you have a hard time convincing anybody to publish it when you came up with it? By the late ’70s very few underground titles were coming out.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I don’t know why Ron [Turner of Last Gasp] put that out. Maybe he wanted to get in with Bill [Griffith] and Robert. Who knows? That’s what most people would probably say.

BAGGE: So Diane was involved with Bill Griffith by then. Was that something that the two of you would be conscious of, as to whether...

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. Around the time we did Twisted Sisters, Trina had Sally Harms wrote an article about us in The Berkeley Barb where we were called camp followers.

BAGGE: The gist of the article was simply to badmouth you and Diane? You mean The Barb thought this was worth printing?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, there was a lot of other stuff in it, but anyone who would know the situation could read between the lines and see that it was a vehicle for Trina to completely put us down. If you read it, you’ll see. Judge for yourself.

BAGGE: It seems like all through the late ’70s you were producing a lot. You did this Twisted Sisters, and then around the same time the Dirty Laundrys came out.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: In the late ’70s I did a lot of work because we moved out here to write, and we hardly knew anybody. I was real isolated. He went on the road with the band, The Cheap Suit Serenaders, for a couple of months. I had several months when I didn’t see anybody.

I had a whole lot of time and I just started working. That was a productive period, but it was because everything else was taken away. I need to be in jail to work a lot because I’m too much of a social gadabout. I get involved too much in life to isolate myself in a studio. I always work sporadically. I’m a real work avoider. That’s why I like the Weirdo deadline because I’m real project oriented. I can work really hard for a period of time, and then I just want to do something else.

POWER PAK

BAGGE: So when you started doing Power Pak #1 did you have an idea in mind for a theme for a whole book? Did you look for a publisher?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I had all these stories. I always keep a notebook of my ideas. I can’t remember if I talked to Denis Kitchen about printing it or not. I think I just did it and then took it around. I don’t remember.

BAGGE: You don’t remember why you took it to Denis Kitchen?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I think because he was nice about it. Denis just came out and visited and saw it and he said that he’d publish it.

BAGGE: I think the anthology [Love That Bunch, released by Fantagraphics in 1990] is a great idea because you’re recounting your whole life’s story in there. The sequence of events tend to jump around in your comic books. The anthology makes a strong story all together.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I think the way I put the book together is pretty good because I try to make it fairly cohesive.

BAGGE: This second one, Power Pak #2, came out around 1981?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I was working on that when I was pregnant. I was determined to finish it before I had Sophie because I figured I wouldn’t be able to get anything done.

BAGGE: This second issue of Power Pak was also published by Denis Kitchen. If the first one didn’t sell well, is there any reason why he agreed to do the second one?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I think he liked the books. He didn’t seem to make any money on it, but he liked the work.

BAGGE: When I read this second issue of Power Pak I was really worried about you. I just thought you were going crazy. It seemed like your negative self-image was reaching crisis proportions. In all your comics, you would swing from being self-deprecating to being a bit of a braggart. You’d praise yourself or show off (the cover of Power Pak #1 shows you doing 18 things at once) and then at other times you’d count all the mistakes you made in your life and show yourself in really embarrassing situations (on the cover of Twisted Sisters, you had yourself on a toilet). In the second Power Pak, those swings that you were taking were sharper than ever. Did this have anything to do with your being pregnant?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I had intense hormonal emotions about everything. Also, a lot of the stories I did up to that time about my family were in the distant past. The one I wrote about my grandfather dying had just happened, so this stuff was much closer. I had much more raw emotions about it. I just came back from the funeral and I was compelled to write this story [“Grief on Long Island”]. It’s like self-therapy.

BAGGE: I thought this had to be the most neurotic comic book I ever saw. It was so intense. A Jewish woman I know said she thought it was “too Jewish.” This woman liked your work but she just thought this was too much. I saw what she meant. You’re reading it and you’re enthralled by these stories — and this is generally true of everything that you do — but you can’t really say that you’re liking or enjoying what you’re reading, but you keep reading it anyway. In fact, sometimes it’s almost like you’ll get irritated and pissed when you’re reading it. With this particular one, you’re wondering, “What is she doing to herself, and what does she want me to feel?” The story I’m trying to find that’s really ...

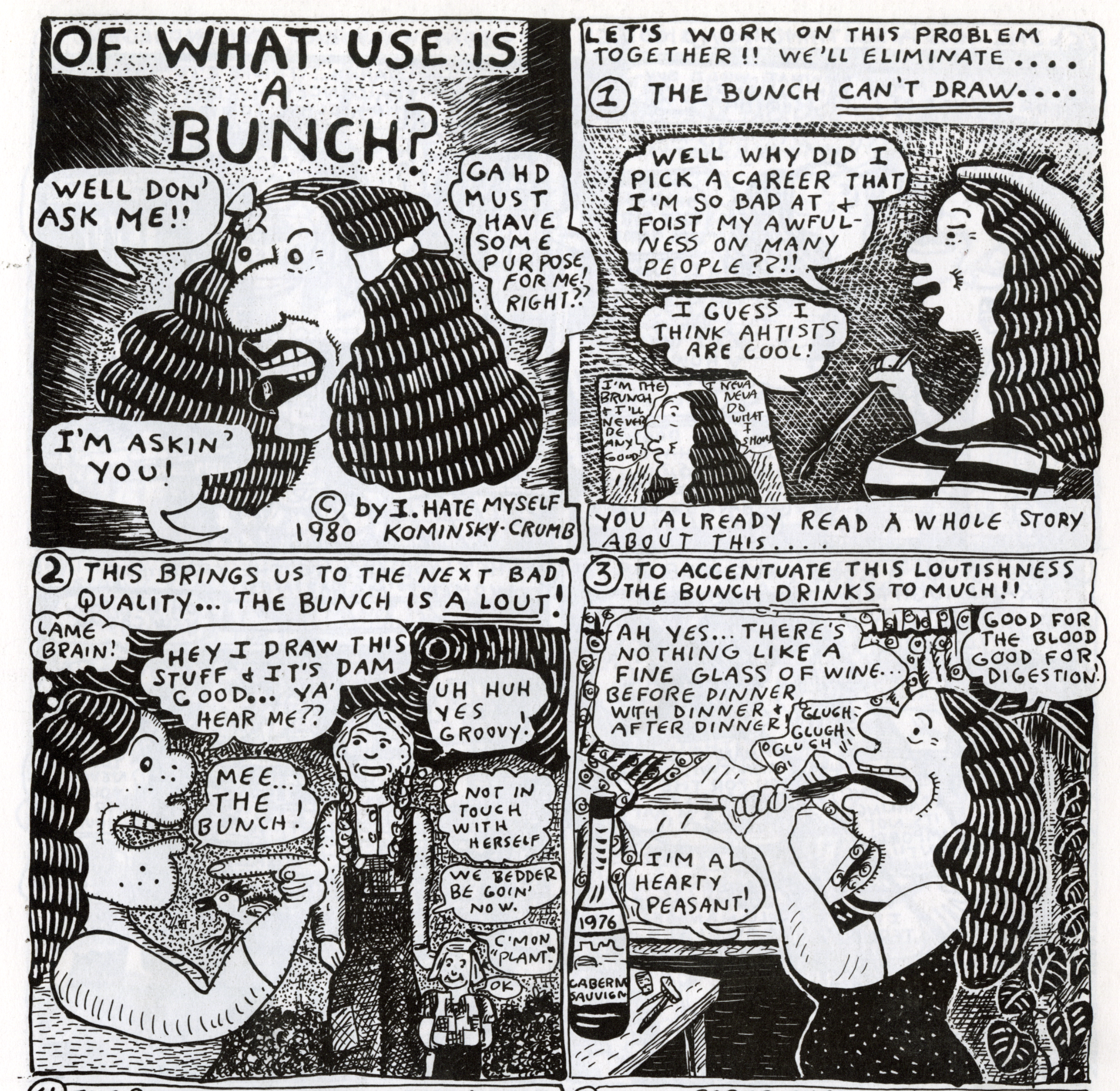

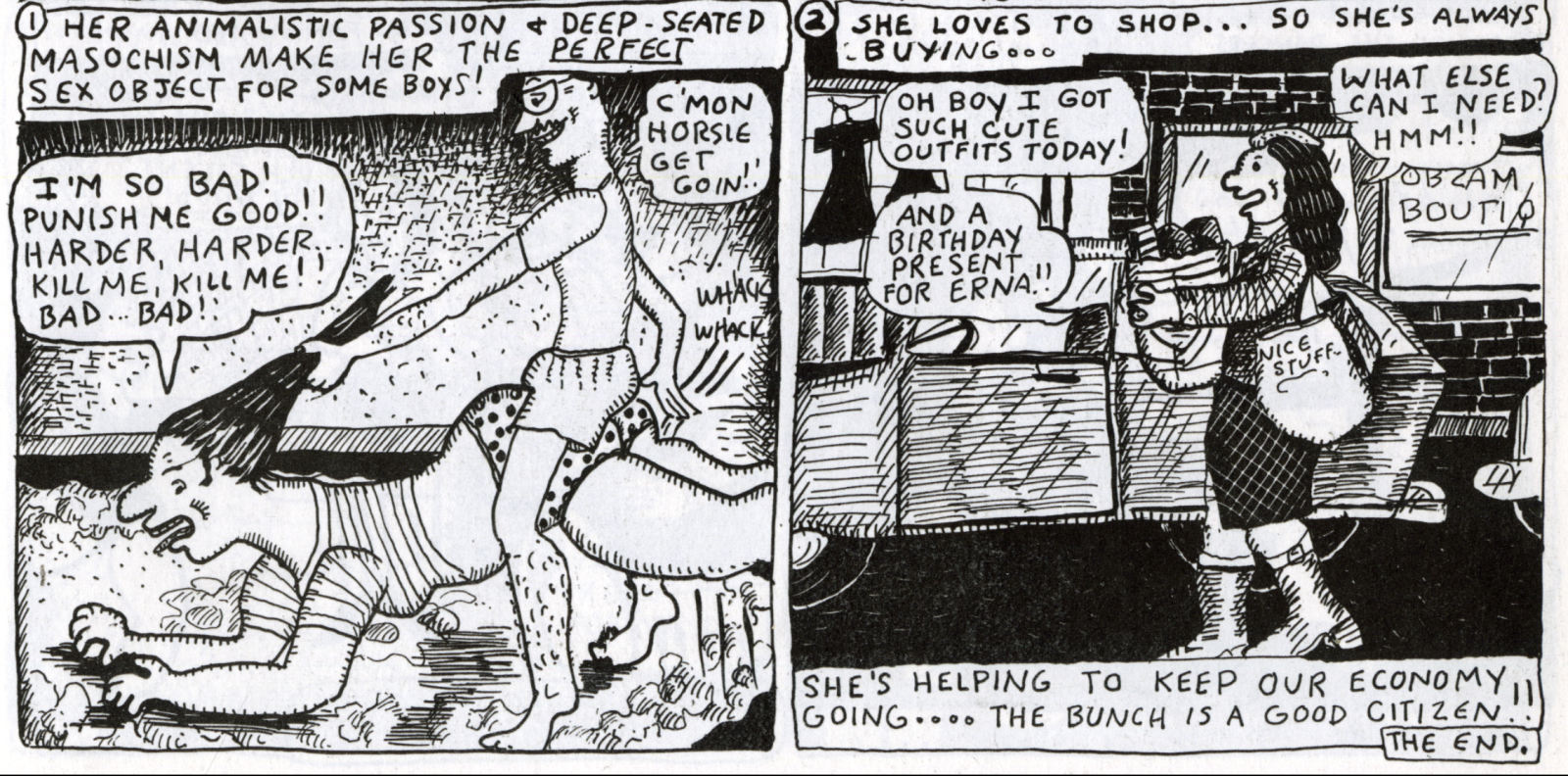

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: “Of What Use Is A Bunch?” That’s my favorite story. That’s a pivotal story.

BAGGE: Yeah. Exactly. “Of What Use Is A Bunch,” Power Pak #2. This is like the epitome of all the comics that you were doing up to that point. In what sense is it one of your favorites? For the same reasons I’m talking about?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. It’s really dense, and it captures what I was trying to do in all those stories, but heavily satirical too. It’s really black, as black as I can get. That’s what really makes it for me.

Somehow it synthesized. All this stuff just came together in this story. It’s a real cohesive story. A lot of my stories meander, but that story’s real tight.

BAGGE: I love your drawing in it. It’s extremely focused. You list 13 reasons why you’re just this horrible, horrible person [Laughter.] Were you in a black mood when you did it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: When I was doing it, I was in a good mood. I was laughing when I was doing it.

BAGGE: Then at the end, you say you didn’t want this to be relentlessly negative, so you come up with two reasons why you’re OK and they’re both self-deprecating. One reason why you’re OK is because you’re a perfect sex slave for Crumb, and the other reason is because you’re such a shopaholic that you keep the economy afloat. It was like two more reasons for somebody to hate you.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. It’s really great. I love it. But it disturbed you when you first read it?

BAGGE: I think people who read underground comix would be really sympathetic because it has a lot to do with being a reject and having a crazy neurotic family. Just about everybody who would have some kind of attachment to a magazine like Weirdo went through the same thing. Probably the only thing they can’t relate to is the mere fact that you would tell it so honestly. In all of those early stories, it usually wasn’t until the third or fourth time I read it that I would think, “My gosh, she’s drawing her parents having sex here.”

You approach walking down the street in the same way that you’d show your parents having sex and beating the hell out of each other. There’s no buildup. You just show it. For years of having this comic book, Twisted Sisters, it wasn’t until preparing for this interview that I said, “She drew herself sitting on a toilet bowl right on the cover!”

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: [Laughs.] Pare it down to the basics. That’s what you’re in for if you buy this. You had better be prepared.

SEX-CRAZED HOUSEWIFE

BAGGE: Since Power Pak #2 (which seems like a culmination of everything you were doing up until then) everything you’ve been doing for Weirdo and other publications — it seems like you’re keeping a diary, you’re usually recounting something that happened the last time you went to Paris and things like that.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Ostensibly I’m recounting, but I’m really not. I use a recent incident to illustrate a point. I have the seed of an idea, and then I’ll focus around some recent event and sort of tell that. It’s hard to explain ...

BAGGE: Another thing, I think people might have a harder time accepting your more recent work — even though the subject matter might be less intense or grim — because your life’s been fairly happy or stable lately. Like Robert, you’ve started manufacturing your own misery. Now people feel less sympathy whereas they could sympathize with the hell you went through when you were younger. A lot of people might be going through some more real kind of hell, like if they’re a junky, or broke, or both, and here you are in Paris manufacturing misery.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: But I’m just totally making fun of myself. Here I am middle-aged; I’ve got everything I want, and I’m still miserable. You get those first things taken care of — like in your 20s you’re just worried about eating and paying rent and “What am I going to do with my life?” — and by age 40 you usually get that somewhat together. Then you’re on some kind of quest for personal truth or whatever you want to call it. You think that when you get some degree of material security your problems will go away, but they just take on a more esoteric aspect. You refine the problems. They don’t become any less painful. You just end up peeling away some of the more obvious things.

To me, the more I’m in an ideal situation ... Like my 40th birthday, I was in the most beautiful place in the world and I was having the most intense anxiety. It seemed so out of place and I had so much guilt. It’s like, “What am I doing with my life? I should be working. Why am I here? Why are these people being nice to me? Why did I have this child and bring her into this fucked-up world? What if terrorists come here?” Everything! It gets more absurd and great to write about. I still don’t care if people like me or hate me. I never did.

BAGGE: Does this also make you feel like you’re real suspicious of happiness? You don’t trust it if everything’s OK? You expect disaster around the corner?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Right. Of course. All Jews feel this as a collective paranoia. I worry about Robert dying or me or the Sof...

BAGGE: Or the house burning down.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I don’t care about the house burning down. I don’t care that much about stuff. I just worry about Sophie and Robert. If I die she won’t have a mother. I worry about my health. That’s why I gave up swilling and puffing.

Last year our house almost burned down, so I put Bob’s sketchbooks in a vault.

BAGGE: And the year before that was the flood?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, I got all the sketchbooks and artwork and personal photos out of the place, and I didn’t worry about it. I didn’t know how little I cared until then. I knew that everyone would be OK, we could get the animals out, and I could get all my personal stuff out. I figured we’ll just have some adventure in life. That’s all right.

BAGGE: Robert says you always feel compelled to move all the time anyway.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I used to like go just pick up — as soon as everything got together, I always wanted to tear it up — but we’re pretty attached to our little parched hell plot here in this gawgeous valley!

BAGGE: Before you started doing comics did you feel as compelled to say something in your paintings? Were you trying to get something out in the way that you do in your comics?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I tried to be expressive in them, but I couldn’t tell my stories. Comics was more finely honed to what I wanted to do.

BAGGE: Do you still feel just as strong a compulsion to tell all as you did when you first started?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s more esoteric than that. Not to tell all but to tell something.

BAGGE: Do you feel as much an urge these days to do comics as you did when you first started?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It builds up. That’s the way I work. The pressure builds up — ideas — and then I have to tell them. I feel that way right now. I have a couple of ideas stewing that I write down: one idea will take prominence.

BAGGE: I’m sure you’re aware that you show things and tell things about yourself in your comics that hardly anybody else will.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I don’t understand why. [Laughter.] I don’t feel anything about it.

BAGGE: So instead of thinking, “What’s wrong with me,” you just wonder what’s wrong with everybody else?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: [Laughs.] The entire world to me is in a state of denial.

BAGGE: They might admit these things to their best friends, but they don’t commit it to print and show it to 7,000 people.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Well, the thing is, in my stories I choose what I reveal, and those are things I must feel fairly secure about. There are other things that I don’t reveal that I probably couldn’t stand to have anybody know about. You’re assuming that you’re seeing everything, but you’re not. What I show is stuff that I can handle. That’s stuff that I have worked out. There are things that I couldn’t possibly write about.

BAGGE: Did you ever think that you were able to do comics because you were in San Francisco in 1972, where pretty much the attitude was to do whatever you wanted? I imagine that otherwise it would have been impossible.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I would have had a different career completely. I would have gone to medical school. It’s what I’m really good at.

BAGGE: If you were young, college-aged now, you might be taking that track?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. The times are so different. The pressure’s on. It’s about survival. Starting right now, you can’t even buy a house unless you have $500,000. That would be so scary. Also, I’m real drawn to medical stuff.

JOANNE BAGGE: You like blood and guts?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah. I like science. Everything about the body’s fascinating to me. I discuss diagnosis with my doctor friend. He calls me up from the hospital all the time and we talk about the latest trendy conditions and everything.

BAGGE: Do you feel like you’re constantly forced to justify and explain the comics that you do?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: More than I’d like to. I don’t know if it’s a litmus test for people who I can be friends with, but I find that most of my close women friends really like my work. Occasionally other women who I think will like it are really horrified by it. Sometimes I’m taken aback by their reaction. They’ll say, “Gee, Aline, I really feel bad that you’re obsessed with a negative self-image. I think you’re really beautiful.” [Bagge laughs.] I don’t know what to say. Then I realize that I shouldn’t have showed them this work.

BAGGE: Have you ever completely flipped anybody out? Or somebody might have gotten to know you, and they see your strips and they’re like, “Holy Mackerel!”

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Um-hmm. I’m living in a small town. I get to know people and I think they’re more sophisticated than they are. I’ll show them something, and they will flip out. I give people Power Pak, and they just don’t get it.

JOANNE BAGGE: It didn’t exactly change their life forever, huh?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: [Laughs.] Or they won’t have anything to do with me or they won’t let their kids come over. A couple of people have said that it’s changed their life. One therapist from Palo Alto wrote me and said he was using my comics in therapy. He made couples read Dirty Laundry out loud. Someone else did a play of my work somewhere for some school theater group.

BAGGE: [Laughing] Elementary school?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: College, wiseass.

BAGGE: One story that came out recently that had a very strange effect on people that I knew, especially women, were the “Sex Crazed Housewife” stories that you did in one of the recent Weirdos.

Robert’s always recounting and bragging about his sexual escapades and people seem to accept it, but when you did those stories, for some reason they had a harder time dealing with it.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Fuck them.

BAGGE: That’s all you have to say about that, huh? Did people make any strange comments to you about those stories?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Oh, yeah. People found them objectionable. Some women really liked them, though. Most middle-aged women I know have strong sexual fantasies, especially women who are stuck home with kids and aren’t getting out in the world. You have to be goody-goody so much of the time that you don’t get to be that wild wanton slut that I think everybody has in them. [Laughter.] I think in order to be sexually fulfilled, you have to have a little extra-curricular sex play — at least flirtation ... sheesh … or good filthy fantasies! What do you think, that part of you dies? You start having extreme sexual fantasies about everybody.

BAGGE: Do you think that some women react negatively to it because they’re trying to deny that they have those same kind of thoughts?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s presumptuous to say that about other people. I don’t know why they would react that way. I assume that most healthy women have those thoughts, and if some women are angry that someone’s expressing that, they must not be in touch with something. Maybe some people aren’t very sexual.

I like to be a catalyst sometimes. I’ll be with a group of women, and we’ll be drinking (not me, of course), and I’ll talk about stuff like that. I’m always interested and amazed that everyone else had equally bizarre thoughts.

JOANNE BAGGE: You brought up some taboo subjects when we were at your friend’s house, and a lot of the women were pretty shocked by the way you were talking, but after a while they were all telling their stories. Did you pick up on that?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, I picked up on that.

BAGGE: You didn’t shock us at all, but I was surprised by the things you’d bring up with people that you’d just met.

You were recounting the story in that comic you did with Robert from Weirdo #16 about how after you had Sophie you got an abortion and then you thought you were pregnant again and all of a sudden you had this huge period. Their jaws were hitting the floor. It wasn’t like they were outraged that you had an abortion. They were surprised that you were talking about it so casually for the very first time that they met you.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: That’s the way I am. Everything comes out in my work and in my personality. I don’t have a real sense of boundaries between me and others (my therapist told me this). I don’t have that self-censorship. I can’t help it.

BAGGE: When you look at your early strips, do you still relate to them? Do you feel like they’ve changed a lot?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I’ve honed it down to where I feel like I make more of a point in the story. The early stuff rambled on. I think it had a cumulative effect, but I didn’t know what I was doing. Now I have a clearer idea in my mind when I start out writing the story. I think that I probably like the later work better.

BAGGE: Do you feel that you have changed from the person who was doing the earlier strips? You seemed almost repulsed when I brought out this “Goldie” story (from Wimmen’s Comix #1).

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: [She looks at the comic and points to a panel.] Larry Todd did the shading in her face.

I’m much less fucked up. I still feel like the same person, just older and wiser. There’s a definite continuity. I remember who I was, and when I look at this I remember how I felt then. I think it’s OK. It seems sophomoric to me and influenced by that whole hippie ethic. I think I’m more black and cynical now in a certain way.

THE BUNCH

BAGGE: Where did the “Mr. Bunch” character come from?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I’ve felt I had a strong male side. This very critical, analytical, nasty side that would counteract the romantic female side. It just took a while for me to actually draw it, but it was a presence that I always felt.

When I became pregnant he left. There’s an anima and animus in everybody I guess. I find that part of me is unusually developed for a woman. Sometimes I actually feel like I’m a man eavesdropping on other women. Sometimes I get that feeling, and other times I don’t. I’m conscious of those two sides real strongly. Sometimes they’re at odds.

People were calling me Honeybunch before I even met Robert because my last name was Kominsky. [Honey Bunch Kaminski is a Crumb comic character.] At first I was kind of flattered by it, but then it started getting on my nerves. I saw Honeybunch as a cute, cuddly little victim, dumb and passive and compliant. I wanted to make the thing the exact opposite, a strong, obnoxious, repulsive, offensive character, but with a name that related to Honeybunch, so I shortened it to the Bunch which sounded disgusting. I was only going to do it as a one time thing, but it sort of grew on me.

BAGGE: Do you actually enjoy and relish making your mother into this “Blabette” character?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Especially at first. I’ve sort of exorcised all of that, so I don’t think I’d do it quite as hatefully now—although in the last story I did, didn’t I?

Now I feel real guilty for having portrayed her so hideously. That makes me be nice to her. I think, “Oh, God, what if my daughter drew me that way?” I’m sure she will.

Even if she saw them, she wouldn’t notice that they were about her or care. Once she came to my house and there were paintings all over the room, and she said, “Oh, who painted these?” I said, “I did.” And she said, “I didn’t know you painted.” [Laughter.]

BAGGE: So your mother’s never read your comics then?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. She’s oblivious to me. She’s a really self-centered person. I think that ever since my childhood I’ve been telling her I want her to look at me and see me and know me. I think putting her in those comics is an extension of that need to be noticed by her, even if she doesn’t see them.

BAGGE: She must know you do cartoons.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: She never asks to see them. She doesn’t care what I do. [Mimicking her mother] “Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. How’s the cartooning business? Oh, terrific. Oh, good. All right. How’s Robert? Where’s that ‘Sopheeya’? Let me talk to that Sophia. Where is she? Is her hair still blonde?” [Laughter.] She loves the Sof.

BAGGE: But it seems like you portray your [maternal] grandmother in a real positive way.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: She’s really a sweet and compassionate woman. She has all those stereotypical bad taste traits, Jewish modern. She’s in Miami. That’s why I go to Miami. I got real strong support from her in my life, and I go back to her.

JOANNE BAGGE: Do they get along well?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. They fight.

BAGGE: You hardly ever draw your brother in your comics.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s painful to me. I drew a little bit of him, “Akkie.” I think that’s one of the most painful stories I’ve drawn. My brother was really horrifying and tragic — not funny.

I was really close to him, but he stole from me too many times. He put me through so much drama. If you’ve ever been involved with a junky, you know what it can be like. I can’t handle it anymore.

It’s tragic because he’s really smart, and he’s a talented writer. He’s got a really black sense of humor. It’s very painful to me because I don’t see much hope for him getting out of that. He’s been fucked up on drugs for so long that he’s never developed much in the way of coping skills.

BAGGE: How about other people you write about in your comics? Do they ever recognize themselves? How about the woman you called “Valerie Feldman” (from Power Pak #1)?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: She asked me not to print it and I did anyway and she never talked to me again.

BAGGE: Since you almost always do stories about yourself or based on yourself, that story’s kind of unique because it was about someone else.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It’s such a great story, and it’s true. I got involved with that husband of hers. He was an Hispanic black guy. He was into hypnotizing people, and was like a voodoo doctor. She was under his spell. It was such an unbelievable story to me; I had to do it.

BAGGE: In your stories you approach things in such a matter-of-fact manner that it’s hard to tell when you’re taking artistic license. That’s literally true, that he hypnotized her? It’s the same thing in your childhood stories. In one cartoon where you stayed out too late in the city, you showed your father beating your head against the wall. It looks like a cartoon effect, just an expression showing how mad your father was, but he really did bonk your head against the wall.

JOANNE BAGGE: He did!?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Oh, yeah.

BAGGE: When I read it I laughed when I got to that part, but it couldn’t be a very funny memory for you.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No, it isn’t. It’s painful.

BAGGE: But you make these painful things look vaguely amusing. Are you aware of that in your strips?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: No. That’s just the way it comes out.

BAGGE: And when you reread your stories?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Sometimes I recall the original emotion, but, at this point in life, I’ve told the story so many times that history becomes something of a myth aside from the real thing. By the time I write something, it already has that degree of detachment usually.

BAGGE: In your more recent strips, do your friends still object if they recognize themselves in it?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: They’re flattered usually. I’m really careful. Ever since I did the “Valerie Feldman” story, I only use people peripherally.

BAGGE: When Crumb writes about himself — he makes himself look like a nut. In his “My Trouble With Women” stories, he makes all these women he got involved with look like nuts, but you always come across as being this pillar of sanity. In “Bob’s Midlife Crisis” he’s going nuts, and you just keep reminding him of his duties, without being a shrew. In your stories, especially in this second issue of Power Pak where you’re going nuts, Robert always appears like the exact opposite of the way he appears in his own strips. He’s like this pillar of sanity for you.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Yeah, I guess we both lean on each other pretty much. Maybe it goes back and forth. I don’t know. Maybe we take turns. [General laughter.] Hopefully we’re not both flipping out at the same time.

BAGGE: Lots of times you make men you’ve gotten involved with look really jerky, but Robert never comes across looking jerky.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I still love him.

BAGGE: Huh! Well, there you go. I guess that’s his saving grace. So Lord help him if you ever fall out of love with him.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I cringe at the thought.

BAGGE: How about your first husband? Is it difficult to write about him? You pretty much only wrote about him once.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: That was ages ago … I don’t think much about him now. I still hate Jewish men though!!!

BAGGE: How does Sophie feel about being in your comics. Do you have any idea?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: She gets a laugh out of it. She got a kick out of seeing her own work published. She was in the Zippy strip a couple of times in the paper.

BAGGE: Ever since she’s been a baby she’s been appearing in strips so to her it’s completely normal. Do you ever think that when she’s an adolescent she might have some bizarre reaction to your comics?

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: I think she’ll be really embarrassed by us in general. Dorky, weird parents. I expect the worst. That strip you did recently about that teenaged girl, [Babs] Bradley and her mother, I can imagine those being me and Sophie. I can totally identify.

She’ll probably hate Robert too because he’s so eccentric. He doesn’t drive. He draws for a living. He’s weaker than his wife. What kind of twisted role-models are we? Obviously she’ll be really embarrassed.

BAGGE: When I was still editing Weirdo you guys did a “Dirty Laundry,” and you did one panel where you showed Sophie masturbating. I got a lot of letters from people who were really freaked out by that. Like one I got from a cartoonist who said he hoped Sophie sues you for character assassination when she gets older. Stuff like that.

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: It seems like a real normal thing. All kids do it. We’re normal and matter-of-fact about it. I’ve even masturbated and Sophie’s come in and I haven’t stopped. [Laughter.] I’ve masturbated in front of him. We don’t think anything of it. [An eavesdropping Crumb looks at Aline in amazement.]

BAGGE: [To Crumb] Get outta here! [Crumb leaves in a hurry.]

KOMINSKY-CRUMB: If you make a big deal out of it, you could drive the kid nuts. Putting it in the comics sort of demystifies all of that stuff. If you’re drawing your kid it would be one typical thing that your kid would be doing, so you would have to put it in.

Imagine how uptight that cartoonist guy must be sexually. That’s all I can say. If people react to something like that, I think, “Jeezis, poor fool.”

BAGGE: I shouldn’t have used him as a example because there were a lot of people. I just thought it was ironic of him because he does such strange comics himself. I was surprised that he’d be making these distinctions. Who knows what he really thinks?