From The Comics Journal #118.

[Ed. Note]: This interview was given in response to a 1987 debate about Marvel and DC rating comics (fueled by a comic shop being closed due to community pressure/the obscenity charges facing Friendly Frank's, which eventually led to the formation of the CBLDF). DC announced new guidelines, with new ratings — "Universal, Mature Readers, and Adult" — and certain creators, including Frank Miller, Alan Moore, Marv Wolfman, and Howard Chaykin, among others, objected to not having been included in the decision-making process.

GARY GROTH: The first question I wanted to ask you is: Do you consider it a victory of sorts that DC has dropped the “Universal” label from their comics?

MOORE: Well, from my own personal point of view, it’s not something that I consider a victory because I never really considered that I was waging a war. I mean, obviously I’m not speaking for Frank [Miller] or Howard [Chaykin] or Marv [Wolfman] or any of the other creators that signed the various petitions during the furor about the ratings system. But, for my part, it was never intended … well, as a conflict. It was simply a case of DC announcing that they were basically bringing in a new system, which I strongly disagreed with.

I signed the petition to make them aware that I disagreed with it. DC reiterated their stance upon the rating system, which seemed to me to indicate that they had no intention of changing their position. And when that became clear, I simply quit. It was as simple as that. I certainly didn’t want at any point to indulge in any form of moral terrorism. I’ve stressed this very clearly to Karen Berger. When I was talking to Karen over the phone, she was asking me, basically, what sort of chance there was of me coming back to DC, and what DC would have to do for me to work at DC again. I explained to Karen at the time that there was very little chance of me returning to work at DC because, basically, that wasn’t what I’d been attempting to do. I hadn’t been quitting DC as a bargaining point, but simply been quitting DC. To me, that was the full stuff. It wasn’t an attempt to say, “Well, I’m going to quit DC unless you do this, this, and this,” because that, in my opinion, would have been bringing the same sort of pressure on DC as I was criticizing the various retailers of bringing to bear. So if I had been angling with DC to try and get them to cave in, I certainly wouldn’t have told Karen that there was no chance of getting me back because that would have been the only possible bargaining tool thrown straight out the window. But I was very adamant about that, that it wasn’t an act of moral terrorism. It was purely the only way that I thought that I had been left of registering my disapproval of DC’s new system.

I mean, this is all something that happened six months ago. It seems very much like a closed book to me now, and it was simply a matter of me quitting the company when I no longer felt that I could abide by their practices. It wasn’t an attempt to bend back that company to my particular way of thinking, and I think that if you re-read my editorial in the [Comics] Buyer’s Guide (printed in Journal #117), I think that somewhere in there I do stress very strongly that if DC wishes to bring in a rating system, then they have every right to do so. But, as a creator, I’m under no obligation to go along with that, and I have the right to take my work elsewhere. So, that was my basic position. So from my point of view, no, I wouldn’t say that I thought it was victory. I’m glad that DC has abandoned the rating system, obviously, because I didn’t agree with the rating system, I thought that was bad for the comics industry. But, I don’t feel any great sense of victory about it.

GROTH: Well, let me ask you this just to clarify this particular point. If you quit working for DC because you couldn’t abide by their newly instituted policies, and they abandoned those policies, on what basis would you still refuse to work for them?

MOORE: Well, this gets down to sort of personal things, because in the petition that we put in the Buyer’s Guide, we originally said that we didn’t like the new system that DC seems to bringing in. And, if at that point DC had said, “Oh, well, we hadn’t realized that we’d done anything wrong, but let’s all talk about it, [see] what we can come with,” then I should have mentioned that there would probably have been no problem at all. But instead DC decided to stand by their decision, which is of course their right, and as a result I left.

Now, since then there have been a number of other factors. One is that in the time since quitting DC, I’ve put DC completely out of my mind, more or less, and have been thinking about other things that I’d like to do. So, you know, just on a purely personal level there are other things that I’m interested in doing now, that don’t really involve DC. On another level, just the behavior of DC as a corporate entity during this time of troubles has, to my mind, left much to be desired. I was very upset about the firing of Marv Wolfman. And I remember that before Marv had been fired, when he was worried that he might be, I said to him that certainly anybody who fired somebody for standing up for a moral position, could not really count on my services in the future. And that’s something that I still feel. I don’t really want to work for a company that fires people over mailers like that. And there was various other things that I don’t want to go into too deeply, but certain other attempts at coercion and things like that, and perhaps things that would have been better left unsaid, things that I found a little bit unseemly in a major comics company. And, I have no desire to rake over these other things that to me are yesterday’s breakfast and six months dead. There were certain factors during the time since announcing my decision to quit working for DC and the present day, which have not really enhanced my opinion at DC Comics. So there’s a certain amount of disillusionment with DC. It’s nothing that I want to make a great noise about. Like I said, they’re perfectly free to carry on doing business the way they see fit. But, to a certain degree, I’m disillusioned with them, and really have no plans whatever they’re doing regarding the rating system, to work for them again. Although, I certainly applaud their common sense in abandoning the rating system.

GROTH: Your disillusionment with DC would indicate that you think they’ve abandoned certain principles that they previously adhered to. And what I’d like to ask is: What principles do you think they’ve espoused that they’ve abandoned?

MOORE: Well, I’d say that it does come down to specific incidents, sort of personal things. I mean, I’m not in a position to say what they’ve abandoned because I don’t really know for a fact what DC’s moral stance was in the first place. And I’m sure that you find this when talking to professionals, “Well, I’ve heard of a couple of instances when people are alleged to have been treated less than fairly by DC, but they have never attempted to mess around with me.” So, until they do so, I’ll keep an open mind on the subject. However, there were sort of veiled threats, and things like that; you know, not big, serious, major threats, but sort of little niggly attempts at coercion which I found a little bit distressing because I don’t really like to be treated in that way. There was some abrasive and personal comments, which, again, I found distressing, because I went out of my way not to bring personalities into it. And indeed in the Buyer’s Guide article I didn’t even mention DC Comics. I was talking about publishers in generic terms. But certainly, I never wished to isolate individual people at DC or indeed anybody as being the villains of the piece or castigating them in any way. And one of the things that upset me a lot about the entire ratings debate was that I did see an awful lot of personal malice flowing around through the air, which is something that I wanted to avoid — obviously still do wish to avoid. But, for all that this leaves its mark it makes me feel … well, I couldn’t actually pinpoint any one particular principle, which I feel DC has abandoned. I mean, as I say, I don’t really know what principles DC had to start with.

GROTH: Right! [Laughs.]

MOORE: It is just a sense of personal dissatisfaction, and if I don’t feel 100% happy with the people that I’m working for, then this makes the work itself less enjoyable, and I’d rather be working elsewhere. That’s basically it.

GROTH: Did you think that the way in which DC reacted to your protest was … well, did that surprise you?

MOORE: No. It didn’t surprise me. We were making the protest because it was a protest that needed making. Some things you do whether they have any hope of practical success or not, just because you consider them to be right. Which was why we made the protest.

Now, I would have hoped that DC, in the first place, would not have gone about the ratings or the labellings or whatever affair without consulting the creators. I would have hoped that in the first place, that we would have had a chance to discuss this before the whole thing ever reached the public eye, so that all of this could have been avoided. But that didn’t happen. I was a little surprised by that. We felt that the only way we could tell DC how we felt about it was in the form of the petition. Now, I suppose that DC had gotten a clear choice when they saw the petition, that they could always have said, “OK, it looks like we might have made a mistake here, let’s all sit down and talk about it, and see what’s going on.” Or they could have done what they chose to do, which was to take a tough, hard-line, no-nonsense stance — by simply buying the opposite page in the Buyer’s Guide to print their guidelines as a way basically of telling the petitioners on the opposite page that there was nothing going, and that petitions didn’t make any difference to DC’s position at all, and that they were going to go ahead and do it whatever [they] felt. That was the stance they took. I think that it was misguided. I think that if you ask the people at DC now they’d probably agree.

I couldn’t say that I was that surprised by it, Gary. I’ve dealt with big companies before, and sometimes a corporate entity makes grotesque mistakes that the individual people comprising it perhaps wouldn’t make if they thought about it on their own for a little while.

GROTH: Did DC at any time ever call you up after the protest and in essence say, “Perhaps we were undiplomatic about this, and let’s talk it over”? Anything to that effect?

MOORE: Well, I don’t actually recall anything specific along those lines. I mean, DC were anxious to reestablish contact once they realized that we were serious. You see, after the protest, I made it clear to DC that it would affect the chances of me working for them under those conditions. That there wasn’t much likelihood of me working for them under those conditions. And I think that the attitude at DC was that we were over-heated prima donnas who’d soon cool down. Well. I suppose that for all I know we may have been over-heated prima donnas, but we didn’t cool down. It was a thing which we did feel strongly about. So DC basically took the gamble of saying, “No, we’re not budging from our position.” Which, as far as I was concerned, left me no choice other than to quit. Since then, DC has made attempts at reconciliation. But, they’ve mainly been along … I mean, we’ve offered better financial deals which I found a little distressing because I wasn’t asking for a pay raise, and I would have hoped that no one thought that I was asking for a pay raise. So, there have been various attempts at reconciliation since that point. But nothing has moved me terribly. And, there’s nothing that’s been effective, as far as I’m concerned. Like I said, this is something of a dead issue. It’s a thing where I quit and that was a final decision. And nothing has happened between then and now to make me change my mind.

GROTH: When you protested … well, DC did two things, one is they instituted the guidelines, and the second is that they instituted a ratings system. And I assume you protested both. Were you protesting the motivations as you understood them, behind implementing these two policies? Or were you protesting the policies themselves? Or were you protesting both?

MOORE: Well, the policies … it was both, I’d say, Gary. The policies themselves are ones that I don’t agree with. If DC came to me before instituting the guidelines and the ratings and they asked we what I thought, then I would have debated it hotly with them. Because my personal feelings about it, as I’ve expressed probably at tedious length elsewhere, are that really it does children no service at all to restrict their access to information about the world. I think that adults have a very distorted view of what childhood is actually like which is clouded by huge pink billowing drifts of nostalgia, and I think, often misplaced nostalgia, and I think that, certainly where I live, the world in which the children find themselves is not by any means a pleasant one. There are intrusions into it by a lot of very grim facts. There is violence in everyday life, there is sexuality, often violent sexuality intruding into the child’s world, and in my opinion, the only way that we can possibly help our children is to give them the information that they need to deal with that.

So, from a personal point of view, as a parent and as a writer, my position was that I do not believe that a ratings system of that sort should be implemented. Now, beyond that, I was also very worried on a political way about the way in which this seemed to have come about. Because it seemed to me that because of pressure being brought to bear by people who, in my book, have brought an extreme moral and political stance, DC were basically caving in in a fashion which I found to be morally cowardly. And which I also associated very strongly with the current political blight upon the American landscape, at least as I perceive it from over here — the moral groups, the moral pressure groups suddenly being able to exert enormous power for themselves simply by the weakness and acquiescence of other people. I mean, it would seem to me that these groups don’t have any real moral or logical reason for assuming the sort of, the positions that they do. It’s certainly nothing which the rest of us should feel honor-bound to respect. I don’t really personally feel that these groups have any automatic right to be listened to. It seems to me that the only reason that they do have the alarming amount of power that they have is because everyone’s frightened of looking immoral when these moral pressure groups are basically making their political stance sound like the ultimate expression of good Christian morality. And it puts people in the position of saying, “We are against good Christian morality.” And many people are too frightened to actually put their case properly or to resist that sort of pressure and that is something which to me, perhaps it’s being melodramatic and overstating the case, but to me that links it very strongly with the concept of “the good German.” It’s people basically not being willing to make a stand against something, even though, in all probability, it’s something that they don’t necessarily agree with. I find that such an alarming prospect, it’s something which I felt, politically, bound to oppose. I didn’t want DC making my decisions for me. If DC wanted to bow to pressures from those sort of sources, then I can’t really argue against them doing that. But, I don’t want them to take me along with them as an employee. So it was a matter of abandoning ship at that point. It was basically a decision on two levels. Personally, I don’t like the idea of a ratings system, I don’t like the idea of guidelines. But, in that particular instance it was also more distress at the way it was being handled politically as well.

GROTH: Well, I have about 30 questions based on that answer. Let me confirm first of all, that a large part of this is due to your perception of DC’s cowardice in the face of outside pressure groups?

MOORE: Yeah.

GROTH: Well, let me tell you this. At the San Diego Con, there was a panel on ratings. And Dick Giordano was on it, and since Dick and nobody else at DC would answer questions about this for six months, I stood up and asked him a question. I’d like to read the question and answer to you and then ask for your reaction. What I said was: “I don’t think that Dick answered the moderator’s first question fully, which was ‘Why did DC initiate the guidelines and ratings when it did?’ Frank Miller and Alan Moore and other creators asserted that DC initiated the guidelines and the ratings system in direct response to outside pressure groups and right-wing organizations, adverse media publicity, and specifically from letters from Buddy Saunders and Steve Geppi. I’d like to find out if that’s true or not.” And Giordano replied, “Our standards were planned as far back as April of last year. We received Buddy’s letter in November of last year, A second or third draft of the standards was shown to Frank Miller before the letter from Buddy Saunders arrived, so I think that we’ve well established that this was the case.” So, in effect, he’s denying that there was any outside pressure. Now, do you think that’s —

MOORE: I have heard this line before. I mean, I’m not saying it’s a lie. I’m sure that Dick said it in all honesty and good faith. But, it was put to me that the DC guidelines had been something that they had been considering for a long time, and I’m prepared to believe that. At the same time, there was a letter, I believe in the Buyer’s Guide, you could check this out better than I could, Gary, that was from, I think it was from Buddy Saunders [owner of Lone Star Comics], it might have been from Steve Geppi [owner of Diamond Comics Distributors], I’m afraid this is a long time back for me, and I’m not even sure of the details of the thing. There was a letter from I think Buddy Saunders — if indeed it was Buddy Saunders, and please check this out before you print it — saying that he had a letter of support from Paul Levitz at DC Comics which he had received after sending his letter to the company. [Moore is actually referring to a letter written by Steve Geppi, not Buddy Saunders. The reader is asked to keep this in mind when reading the next four paragraphs.]

Now, I mean, I’m not sure how else to square those two bits of information together. Either Buddy Saunders is lying, in which case he has put DC into a very difficult position, and I wouldn’t have thought they’d have been terribly pleased about that. Or it’s true, in which case, I don’t really know what to think. I would say that looking at this, I’m not sure whether this happened or not. But what I believe probably happened is that it wasn’t a case of downright evil, but more a case of bad luck and ineptitude. I think that what probably happened was that DC had been considering the guidelines for a while, but that still didn’t stop them choosing that particular opportunity, upon receiving the letters, to try and make a small amount of political capital out of it by appearing to appease the retailers and distributors by saying, “Yes, we go along.” I mean, as far as I remember, the quoted substance of the letter from Paul Levitz to Buddy Saunders was that DC agreed on many of the points in his letter and he could count upon their support, basically. I mean, that’s paraphrasing, but I think that was the basic gist of it. So, it would seem to me that there’s at least the possibility that DC, and they may have been considering a rating system of some sort for a while, but that it was still the letters from the distributors and retailers concerned that actually made them choose that particular time to implement those policies. In my book, it doesn’t really make an awful lot of difference whether they’d been planning them for a while or not, if that was the case, because there was still, as it seems to me, an attempt to maybe make political capital out of the situation by appeasing the pressure from outside. In which case it’s simply morally immaterial whether the guidelines had been discussed previous to that. That’s my thinking on that, Gary, but, as with all these things, I’m living in Northampshire, and this is all happening in New York, in America. I’m relying upon second-hand information for all of this.

GROTH: Let me ask you something else about DC. Is there anything necessarily nefarious about Buddy Saunders sending DC a letter saying something to the effect that, “I would like your comics to be more moral according to my standards,” and Paul Levitz theoretically sending back a letter saying, “Yes, we would like to be moral and responsible publishers, too”?

MOORE: Well, let me just think about that for a second. Well, I don’t think that … well, it’s a free country, Gary.

GROTH: So they say.

MOORE: Buddy Saunders has got the right to send a letter to DC, as indeed has any reader. Anybody in the country has the right to send a letter to DC, and suggest certain changes that they might feel would enhance the company’s product. I mean, we get thousands of letters like every day.

GROTH: Right.

MOORE: Given Buddy Saunders’s position, it perhaps makes it slightly more disturbing, because he can bring a certain amount of financial pressure to bear upon DC, even though probably not a great deal, but there is that element to it. But still, for all that. I would be prepared to say that he’s got an absolute right to send stuff to DC. And to send a letter to DC and ask them to take a more moral position.

Now, that is Buddy Saunders’s definition of moral, and I believe that he explained it pretty clearly in his letters, and I’ve read stuff in the recent Journal where he modifies various statements, but from the initial letter, with the talk about boy-scout super-heroes and, well, he more or less suggested that the characters and the creators themselves were mental and moral wrecks. [Laughter.] Which maybe from Buddy Saunders’s point of view we are, which is fair enough. But it is, at least in my book, a moral opinion which does require a certain amount of debate. Certainly DC has got the right to send a letter back to Buddy Saunders, and to say, “Yes, we’ll go along with everything you say.” That’s fine.

The morality of that is so vague, nebulous, and subjective that I barely want to get into it. But the result of it is that, on a purely practical level, DC were allowing a rather extreme moral stance to go unquestioned, were accepting without consulting any of the other sort of interested parties. I’m not saying that it was actually immoral or the sort of the thing that they’re going to burn in hell for forever. But it wasn’t the way that I’d rather that they’d done business with me. It was something that I found personally upsetting. And, as I said earlier, it was something that I didn’t feel that I could go along with. It wasn’t a matter where I was thinking that Buddy Saunders was evil for sending the letter. Although obviously his morality is totally different from my own. It’s not a question of me thinking that DC are evil for sort of acquiescing to it. Although DC’s reaction lacks a certain amount of spine.

GROTH: Right.

MOORE: It’s mainly that I felt that DC had unfortunately created an untenable position as far my relationship with them went, because they were including me in a decision that they were making regarding the way that they responded to the distributor’s letters, which I really didn’t feel that I wanted to go along with. Did I answer your question, Gary? I’ve lost track of it; I’m quite through.

GROTH: You might even have answered three or four questions, Alan. It seems to me that one of the things you’re saying is that publishing companies can behave morally. And one of the reasons you’re leaving DC is because they breached what you consider to be some sort of moral contract, an implied moral contract between the corporation and its authors. Is that accurate?

MOORE: Ye — Well, it’s not inaccurate, Gary. The word “moral” is a very strong and loaded one. I mean, to some degree, I’m not naive enough to expect any big corporation to behave morally. They don’t. I don’t think I’ve ever come across one where I could say that this corporation has behaved in all instances in the way that I myself as an individual would have. So, yeah, to some degree, anybody who is working for any corporation is morally compromised to a point. And I suppose it just becomes a matter of where you draw the line. There had never been any situation when working with DC when I personally felt that I would be morally compromising myself. I suppose, yeah, you could argue that while working for a company like Warner Brothers, or while working for DC, if they’ve done anything wrong then you’re morally compromised. And, yeah, I suppose that there is a case for that. On the other hand, the first job I got working in the industry was for the music paper Sounds, which was owned by Spotlight Publications which was owned by a company which made missile guidance systems — you know, you’re up to your neck in shit the moment you step into the industry.

GROTH: Right.

MOORE: So that’s something that you do, and you adjust to it. There is a point where, well, it’s if you never bought vegetables from any country in the world that’s got something politically wrong with it, then you’d starve. Much human existence does involve a certain degree of compromise. As long as that’s at a tolerable level, then that’s fine. But, whereas before in my relationship with DC I had never felt morally compromised beyond that basic level of compromise which it seems we must always deal with, in this instance, I did feel that it had overstepped my personal mark. It seemed to me that DC were basically bowing to pressure, either directly or indirectly, from a group of people that I considered to be actually evil. People that I would use the term immoral about, and, so, although that’s a subjective thing in my mind now, I felt that DC had gone beyond the line that I’d drawn.

GROTH: OK, I want to skip back, because there was a period where you said about a dozen interesting things, and I want to follow up on a few of them. If 1 understand you correctly, you were talking about the criticism levied against comics by certain right-wing organizations, the kind of criticism levied by people like the Moral Majority and so forth. And, if I understand you correctly, you were saying that you thought that they were imposing a criticism that lacked an authentic moral authority and that DC was in essence acquiescing to this not because they searched their own conscience and found their conscience to be compatible with the people who were criticizing them, but out of a sense of cowardice.

MOORE: Yeah.

GROTH: Now, I’m wondering if you think that morally based criticism could be levied against DC (or other comics publishing companies) that was in fact legitimate enough for DC to honestly respond sympathetically, and respond to accordingly.

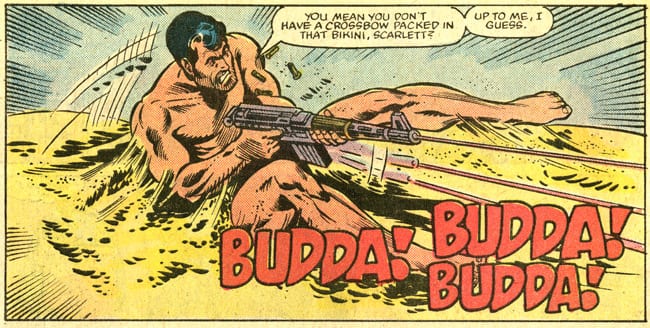

MOORE: I really don’t know. Morality is sort of a dodgy area once you try to extend it beyond the personal, Gary. I mean, certainly — this is not DC, this is all comics — there are certain places where I will pick them up and I will find expressions of sexism, I will find unconscious racism or tokenism, I will find expressions of things that to me do seem to be morally wrong. However, whereas I might write a letter of protest, or promise never to read those comics again, I would never extend it beyond that point. I would never write to DC, or get up a pressure group demanding that they eradicate sexism from their comics, because although it’s something that I feel very strongly about, I wouldn’t feel that it was my right to impose my moral perceptions of the world upon them. This is only my stance, but I really do believe in freedom of speech. This has certainly gotten me into trouble with some of my more radical friends, because I have, in the past, said that I believe that even the National Front, the British Nazi organization should not be denied freedom of speech, which I believe is almost a suicidally liberal stance, but is one that I feel totally compelled to stick to. You know, I’m free to object to any stuff that I hear and don’t like. I’m free to object in public to any stuff that I don’t like. That’s my right. I might level personal moral criticisms about a company that had actually done material that I found offensive, but I wouldn’t expect DC to heed them. It would be nice if they did, sure, but I wouldn’t expect them to necessarily take any notice of them. I mean, it depends whose morals you’re talking about. Please don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that Buddy Saunders doesn’t have morals, I’m sure he does. I’m sure that Steve Geppi has morals. But I’m equally certain that they’re not my morals. And I’m not certain that there is an objective morality. I’m not certain that that’s how the world works, in practice. So, to me, even though I might object to the war-mongering aspects of a book like G.I. Joe, for example.

But my response to that will not be to try and get a campaign to get G.I. Joe taken off the shelves, or put on a higher shelf, or put in a plastic bag, or given a rating on the cover. My response will be to contribute to something like Real War Stories, which will make me feel that I’m redressing the balance in a positive way, rather than trampling over the opposition through sheer brute force. So yes, there may be areas in DC Comics which I would find morally reprehensible...

GROTH: Well, now what is the reason —

MOORE: … Certainly not ones that I would try to eradicate by censorship.

GROTH: Well, would you try to eradicate them through persuasion?

MOORE: No. I mean, what I would try to do was to eradicate them by trying to do something better. I mean part of my attitude to comics regarding say, the work on Swamp Thing and Watchmen is that if I can state my case with greater lucidity, greater impact, then I have a chance to basically make people lose their tastes for those sort of things, hopefully. At least that’s my ambition. If people did start, say, for example, treating women more accurately and realistically in their comics, and if those comics were well enough crafted to be superior comics then I would hope that through a process of Darwinian natural selection that there would gradually be less and less sexist material appearing in comics because they would be perceived by the readers as being more and more dated, more and more offensive. That form of pressure I have no qualms against bringing upon people because it seems to me to be perfectly fair and equitable. And there’s no guarantee that I’ll succeed in it. Any other sort of pressure, I really don’t go along with.

GROTH: I hope you don’t think I’m belaboring this, but I just want to drag you into deeper philosophical waters here. It seems to me that you’re talking about a similar strategy in terms of persuading people to do something or not to do something. In other words, you’re trying to provide something positive rather than something negative, but my guess is that you would probably support a columnist’s right as a writer espousing his principles, to say that you shouldn’t vote for Ronald Reagan because of such and such, which is a negative way to persuade people, rather than saying that you should vote for somebody for these reasons. And —

MOORE: Well, in my instance, that’s a bit of a funny analogy, because I’m an anarchist, Gary.

GROTH: Ah-ha!

MOORE: At least as far as I’m able. I really don’t think we should vote for any of the bastards. [Laughter.] Which perhaps is a pretty negative stance to take. I don’t know. You know, sort of —

GROTH: That could be perceived —

MOORE: Well, obviously, in my comics. Well. I’ve probably done more comics about the horrors of nuclear power than I’ve done about the delights of windmills.

GROTH: [Laughter.] Right.

MOORE: Which I suppose is a vague parallel to what you were saying. And, yeah, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with commenting upon the negative aspects of things, but I think that there is something wrong in actually putting pressure upon … I mean, if there were elements in DC comics that I didn’t like, I would try to do something which could hopefully be strong enough to replace them. Now, in the course of that work, yeah, there will probably be lots of things that said that I thought Ronald Reagan was a bad president and that the Arms Race was wrong and all the other usual liberal concerns that my readers are so familiar with. But I still don’t see that that is actually putting any form of unfair pressure upon people. I really don’t think that Buddy Saunders is doing anything unfair by pointing out what he considers to be negative aspects in comics from his moral point of view. I think that it would get a bit tricky if, having decided that sexism in DC comics was wrong, I would then go to Dick Giordano and say, “Unless you get rid of all the sexism in DC Comics, Dick, I’m leaving.” No, that would seem to me to be putting an actual, hard, physical financial pressure upon DC Comics to do my absolute moral will. That would be wrong. If in a private conversation I said to Dick, “I think there’s too much sexism in DC Comics,” and he said, “I don’t agree with you,” then I’d say, “Fine.” And it would go no further than that, because other people have got their right to their opinions, too. Including Buddy Saunders, including Steve Geppi. It’s like the right-to-lifers consider that they have the right to stop women from having control of their own bodies. The pro-abortionists, as far as I know, don’t actually go around and insist that they have the right to give women abortions whether they want them or not. It seems to me to be similar to that sort of situation. All I’m trying to do is to defend my own territory, I’m not trying to encroach upon anybody else’s, and so whereas I’m only too happy to state my case and to make moral arguments of my own in a forum where people are free to accept or reject them as they see fit. I would never bring pressure, of the kind that I perceive DC bowing to, upon a company to subjugate themselves to my moral imperatives.

GROTH: Right, right Hmmmm.

MOORE: If I sound like I’m being evasive, Gary, then please tell me, because it’s not intended. I’m just sort of —

GROTH: No, no, I think you’re making an interesting point. What you’re saying, I suppose, is that there is a point beyond which you won’t lobby to impose your own moral view on other people.

MOORE: Yeah. I would lobby to make my moral view heard, but not to impose it. I’ve marched with anti-Nazi demonstrations, but I would not go along with the members of those demonstrations who wish to gag the National Front. I believe in making it plain that there is an opposing view, and this is what the opposing view is. But not in trampling upon the view that you oppose.

GROTH: OK. I certainly don’t want to beat that horse to death. I was just going to say that putting pressure on organizations that you oppose morally or politically is probably a recognized device in democratic societies, and whether it’s the Moral Majority or whether it’s Norman Lear’s group [People for the American Way] or whoever, there doesn’t seem to be anything terribly nefarious about that. And one —

MOORE: Well —

GROTH: — of the intellectual pollutants in this whole debate seems to me to be that the anti-labeling faction is content to criticize people like the Moral Majority for trying to put pressure on not only DC but the music industry and the entertainment industry, whereas I think it might be a much better strategy to confront the moral basis for this criticism head on, rather than to simply say that putting pressure on DC is in itself wrong. Do you see the distinction I’m trying to make?

MOORE: I see the distinction that you’re trying to make. I mean, for me, in the instance of the Moral Majority, there are problems. It’s very difficult to actually confront the moral issues of the debate with people who actually do believe literally in the Old Testament.

GROTH: [Laughter.] Yes.

MOORE: I mean, it’s very difficult, as I’ve said in the past, it’s very difficult to mount a rational moral argument against the extremist born-again Christians, when all they really need to do is notice that DC is publishing at 666 Fifth Avenue. I’m not trying to be glib there, but the stuff that I’m hearing from over that side of the Atlantic with the apparent satanic messages recorded in record groups … How do you rationally argue against something like that? How do you rationally argue against zealots? I can see that this is a muddy situation. I understand the Moral Majority’s position, I don’t like it, and I feel pretty much the same way as I do about the National Front in this country regarding the Moral Majority. But it sort of seems to me that I’ve got less against those organizations themselves than I have against the people who capitulate to them. If it seems to me that they’re not capitulating out of finding themselves in moral agreement with the people making the decisions, but out of financial considerations, or other sort of anxieties and fears. That’s what strikes me as frightening and sinister, especially when you get to the state where you can have The Wizard of Oz and Catcher in the Rye and The Diary of Anne Frank taken off of library shelves. That is serious shit.

GROTH: [Laughter.] Right.

MOORE: That is a dangerous line for civilization. I don’t think that to be alarmed at that can be purely written off as liberal paranoia. You’re getting into very deep waters there. In my opinion, if that is allowed to go unopposed, then it could have disastrous consequences. Now, the question is “How do you oppose it?” You could adopt the same tactics as the people you are opposing, which is something that I’ve always felt very, very uneasy about, because it seems to me that you’ve lost before you’ve won, before the fight starts. From my point of view, I might learn that, for example, DC might in the future learn that...well, let me think this through. I would like to think that hopefully in the future maybe comic companies would not have such an automatic knee-jerk response to that sort of pressure. I would like to think that if this whole debacle has actually done anything of any worth, that the issues have been aired and that people in the future might think, “Well, hang on, why do we have to automatically fold in the face of this sort of pressure? Are there other alternatives?” I suppose that that’s my ultimate hope for the situation.

GROTH: That’s pretty optimistic, Alan.

MOORE: Yeah, I know, it’s incredibly optimistic, but I’m that sort of boy, Gary. I don’t know, you’re probably right. I doubt that it’s really going to change an awful lot, but if we didn’t nurture these spouts of optimism in our breasts, it would be a pretty grim old world, wouldn’t it?

GROTH: [Laughter.] Yeah, right. Well, let me ask you to comment on this, because I think your position is different in at least the nuances from that of Frank’s and Howard [Chaykin’s] and Marv’s. You’ve said that you don’t intend to work for DC in the future, and that it didn’t particularly help their case that they did eventually capitulate to your protest. Now, at the San Diego Con, Frank said that he felt that the difficulty between him and DC was “completely resolved.” And the question I have is, if in fact DC did capitulate to the climate of the times, or to opprobrium from outside in instituting the ratings system and the guidelines, and now they to capitulated to four creators who protested, is it overly cynical to question why a creator would work for a company that simply capitulates to whoever they think has the most clout?

MOORE: Well, I think I’ve already answered that one from my point of view. That’s not the of basis that I think a comic book company should work upon. I didn’t think so when it was Buddy Saunders involved, and I didn’t feel that it would be any better if I was making them capitulate. Which is why I said straight away that I didn’t want to work for DC again, and that really, there was no point in making concessions to me, because they wouldn’t alter things. Now, as far as Frank and everybody else goes, I really don’t feel qualified to comment upon that, because I’m, well, great friends with Frank and with all of the others, and also because I’m a long way away. Now, as I understood it, the last time I spoke with Frank, he hadn’t actually said that he’d straightened out all problems between him and DC. I think he was asked by Jenette Kahn, “Does this sort out your problems with the rating system?” which it did. Like I say, if DC had at the beginning after receiving the petition, sat down and talked with us and then said, “Yeah, well, we can see you’ve got a point, and we hadn’t really thought about it, but now we won’t have a ratings system,” then that would have been completely different. That would have been fair enough, and I could have carried on working for them. But, they did, they have now belatedly done the things which could have saved the situation then, so I suppose that on a pure practical level, yes, I can understand Frank saying that the situation is resolved. Now, as I understand it, and this is again at long distance, so it’s probably completely garbled, I believe that Frank has actually said in the Buyer’s Guide that DC’s announcement that it’s going to drop the ratings system means that the ratings system is no longer the obstacle between Frank and DC. Which I don’t think is quite the same as saying that it solves everything. There might be a question of nuance there, Gary, which sort of redefines things a bit, but it’s something that I don’t really feel competent to comment upon, not having actually heard or read what Frank said upon that. But, I suppose that I can see that maybe on a practical level, we were sort of distressed that DC should be bringing in a ratings system and now they’re not. I suppose that one level, yes, they have fulfilled the practical considerations of whether they have a ratings system or not to some degree. Like I say from my point of view, I didn’t want them to buckle under to my moral demands, which is why I left rather than made threats to leave. But I really can’t comment upon anybody else’s stance upon this, because there’s an awful lot of distance, I only speak to Frank about once every six months, probably no more often than I talk to you, Gary, and I wouldn’t want to actually comment on Frank’s stance, or Marv’s stance, or Howard’s. We weren’t doing it, as I saw it, as a solid pressure lobby, because, I know for a fact there are differences of moral opinion between all of us. This is one of the classic dilemmas of the left, I suppose, in that they do not have one consistent model that they can turn to, whereas the right tends to. Do you know what I mean?

GROTH: Sure.

MOORE: So I was never under any illusion that we all felt the same way about things. This was just something that we happened to come together on in that instance, that none of us liked what DC was doing. From my point of view, I would not have wished DC to capitulate to pressure from me, and I did not attempt to do that. And I can’t really comment for anybody else.

GROTH: Let me ask you this, and the reason I’m asking you this is because I don’t think anybody involved in this has been very consistent on the matter, and that is whether or not DC is censoring the creator when they demand or request that the creator change the characterization of a character the company owns.

MOORE: No. I was going to ask you this later Gary, because I’ve seen your bit in that panel discussion about creators asking to do Minnie Mouse and turning her into a prostitute. And if Disney says no, is that censorship?

GROTH: Right.

MOORE: No, it’s not. In that instance, I thought that was perhaps a bit of a strained analogy, because, yeah, if I was going to work for the Disney studios, I would know what sort of product they were doing, if I was working for Star Comics or Harvey Comics, I’d know the same thing. I’d know that, I shouldn’t show Top Dog getting rabies and biting a school child or something. I’d be aware of that. But it was not so much a matter of censorship, as a matter of — yeah, I think that the outside bodies, the right, the moral pressure groups that I was referring to were trying to impose censorship. I mean, I wasn’t saying, “DC is censoring me,” because they won’t let me do Batman the way that I like it or whatever. DC does have, as far as I understand it, predominantly a teen-age audience, certainly a different audience than the Disney studios. And also an audience which does respond in the marketplace, apparently, responds well to stories with a more adult treatment. So, as I saw the conditions of the marketplace when I was working upon it, I took over Swamp Thing, and I probably made the character more adult. We didn’t get any letters of complaint, the sales went up.

Which didn’t surprise me, because as I perceived the audience, the audience wanted something that was more adult; DC encouraged me in giving them something that was more adult which seems to be a pretty straightforward transaction. And as such, because those arc the sort of stories that I enjoy doing. I was still quite able to carry on working at DC. Now, regarding Batman, for example, I suppose you could say that is traditionally a children’s comic book character. At the same time, me and Brian Bolland have got a graphic novel coming out sometime early next year, I believe, which is certainly just as disturbing a portrayal as in Dark Knight. Maybe even more so. I mean, there are some scenes in there I found quite horrific. Now, I suppose that if you feel aesthetically that that is an inappropriate way of doing the character, that’s fair enough, obviously you’re entitled to your opinion. But, in my opinion, that what’s happened with Batman over the last ten years, can’t clearly be labeled as a children’s character, has not been portrayed exclusively as a children’s character over the past ten years. There have been attempts to give him adult edges, and sort of make him like that, which has not gone amiss with marketplace or with the company. DC has not caught Minnie Mouse with Batman, you know. Whereas I personally at the moment have no great desire to do super-heroes again, while I was doing that particular book, DC seemed to be happy with what I was doing, I was happy with what I was doing, Brian was happy with what I was doing, and then there were the readers who liked it. Yet, it might be too extreme, I don’t know. But if DC had said to me at any point, “We don’t think this is right for Batman … ” Well, say for example, when I sent in the synopsis, they’d have said, “No, we think this is the wrong treatment for Batman.” I would never have accused them of censorship. I mean, I’ve sent synopses in to DC, which, on occasion have been rejected for those sort of very reasons.

GROTH: You’re referring to the Joker graphic novel?

MOORE: Yeah, I was referring to the Joker graphic novel. I’m sorry. Batman’s in it as well, but it is the Joker graphic novel, The Killing Joke, that I’m talking about. I have sent synopses in to DC with other characters, and DC has written back, and said, “Well, we like the synopsis, but we do think that it is a bit extreme to try Plastic Man as a male prostitute” or things along those lines. At which point, that is their right. And I would not accuse them of censorship for doing that, which I think was the thrust of what you were saying.

GROTH: Yes.

MOORE: Yes. Of course I wouldn’t. I mean. I know that there are some characters that DC do regard as being primarily for children, or exclusively for children. So, for example, when I wrote my Superman stories, I think that you’ll find that I was touchingly reverent, to the institution of Superman. I had Krypto in there, I didn’t have any big revelations about Superman’s sexuality or anything like that. Whereas with a character like Batman I think that there is precedent for saying that there is more leeway with the character, that he has been treated in an adult or semi-adult fashion over the past ten years, of course with Dark Knight and its success, which proves that to some degree the readership do enjoy that sort of presentation. It seemed to me fair game that I should do what I’ve done with Batman and the Joker in this Joker graphic novel. But, if DC had said at the beginning of that instance, you know, “No, we don’t think that Batman and the Joker should be treated like this,” then I would have either said, “OK, I’ll change it,” or “Well, OK, in that case, I don’t really feel like doing the novel because that was what I wanted to do.” But it wouldn’t be a matter of DC censoring me.

GROTH: Yeah. You wouldn’t begrudge them that editorial prerogative.

MOORE: No. There again, if I had been working on, say, Swamp Thing and they had suddenly said, “Well, you’ve been doing these adult stories for the past ten issues, but we don’t really think that it’s working out, and we’d like you to make it back into a more simple super-hero-y sort of character,” then, I wouldn’t have called that censorship, but I would have retained the right to say, “Fair enough, but in that case I’d rather you got another writer for the book, because that’s not the sort of stuff that I’m interested in writing.” I mean, I’ve got my options open. I can do whatever I want. If I went to the Disney studios and they said, “Look, Alan, we want you to write Minnie Mouse,” and if I were to say to them, “Well, yeah, but I really would like to do Minnie Mouse as a prostitute, because I’ve got a really good story worked out there,” and if they considered it and said, “Yeah, well, actually you could have something. This will be fine. Try and see how it goes.” And then the results had been good, and they liked it, then that would be more comparable, absurd as it sounds, to the situation that I was in at DC. No, I wouldn’t call it censorship, Gary. I don’t think I’ve got the right to, DC owns those characters, and they have got a right to say how they think they should be treated, and we as creators have a right to work on them or not, depending on how we feel about DC’s opinions in the matter. That’s not a censorship situation as far as I’m concerned. I suppose what I’d call censorship is if I’d done those Swamp Thing stories in good faith and then they’d come out with scenes omitted from them or changed after the fact. That’s censorship. But I know what I’m getting into when I take on a character like Superman or Batman, and I send in the synopses and say that this is what I’m going to be doing, and this is going to be very heavy, and we’re going to have some quite chilling and frightening bits here and stuff like that. To me it seems like a fairly equitable transaction. There’s no problems there. But censorship to me is something that occurs after the fact. I wouldn’t say that if DC were to say to me that they wanted a very anodyne version of Batman, I wouldn’t say that that was censorship, that would just be them expressing their prerogative over a character that they own.

GROTH: I also wanted to talk to you about, well, your objections to labeling comics. First of all, you could just tell me exactly what your objection is to that, and then we can delve into that just for a few minutes.

MOORE: I would say that when it comes down to labeling comics, if we lived in a perfectly innocent world, then I’ve got no objections to labeling comics, because to some degree just putting a title on the comic is giving it a label. To a certain degree. But I don’t believe that we’re just talking about labeling here. I think that DC is making great distinctions between the terms “labeling” and “rating,” and I’m not exactly sure if there is a difference there. It’s a very, very subtle one that I’m not quite able to spot. You say we’ve got a rating system in films with R, PG and whatever the other one is.

GROTH: Yeah, X.

MOORE: Yeah, but in comics we’re not having a rating system, we’re having a labeling system. In which it will either be “Suitable for Children,” or “Suitable for 1 to 16 Year-Olds,” and “Suitable for Adults.” I don’t see the difference there at all. Certainly in that respect, I see that putting a rating system upon the front of the comic is, in practical terms, a very dodgy move, because, for example, in the interview that you did with Buddy Saunders, there was talk about the Mylar-bagging practice, and I think that Love & Rockets was used as a specific example. If there were issues that had got things which Buddy Saunders considered to go beyond the line as far as his principles were concerned, those issues, like the one with full frontal nudity in it, would be Mylar-bagged and the other issues wouldn’t be. He pointed out that putting the things in Mylar bags would probably harm the sales, right? Now, it strikes me that although he is not actually forcing writers or artists to do anything different, it wouldn’t take very long before publishers perhaps less scrupulous than yourself, Gary, would say, “Well, look, this is not selling very well. Perhaps it would be better for you financially if you did start toning down this sort of stuff.” And there are a number of ways in which publishers can put pressure upon creative people. I’m not saying that Buddy Saunders hasn’t got a right to sell things in his store the way that he wants, but I think if that precedent was enforced upon the entire industry, if all the X-rated books are being Mylar-bagged as adult and are not selling so well, then publishers are going to start putting more of their money where it’s safe, into books that the readership will have free access to. And I think that that would gradually and inexorably lead to a decline in the standards of the market. And also, I’m a little bit leery about the actual apparent principles behind it. I don’t mean to beat upon Buddy Saunders, because like I say, I’m sure that the guy does follow his own moral principles and rights just a much as I do mine. There was just a comment upon Watchmen. And he said, I thought about it, and I thought, well, if the early issues of Watchmen had been Mylar-bagged, it would have harmed the book and it wouldn’t have done so well. Now, you’re getting into dodgy territory there, because presumably from what he was saying there, Watchmen hasn’t been Mylar-bagged.

GROTH: Right.

MOORE: However, later in the interview, he’s talking about full-frontal nudity, and saying that is one of the things he would Mylar-bag a comic for, as regarding the Love & Rockets decision. Now, there is full-frontal nudity, male full-frontal nudity in most issues of Watchmen. Now, if you colored Manuel’s dick blue, would that solve his problem? Or is it the fact that Watchmen sells a hell of a lot better than Love & Rockets?

GROTH: [Laughter.] I’d have to talk to Gilbert [Hernandez].

MOORE: Yeah. But do you see what I mean, Gary?

GROTH: Yeah.

MOORE: There just seems to be some sort of discrepancy there. It strikes me that books that don’t sell millions, books that don’t sell tremendously well, like Love & Rockets, would be the ones that would suffer from that, because even if he told you something that the artist internalized subconsciously, if Gilbert and Jaime start thinking, “Shit, we need this money to pay the rent or whatever,” stuff like that, “and we’re not getting very much money coming in,” then, “Shall I do this particular story for the next issue, which I was thinking of, or should I drag up this story, which hasn’t got so much sex in it?” It’s something which I think makes for a potentially dangerous situation regarding the future of quality in comic books. I’m not sure how a labeling system is practically of any use, because, as far as I’m concerned … is it enforceable? Are any of these regulations ever truly enforceable? As a kid, I could get hold of anything that I wanted. I believe most children can, if they want to. And I don’t think that sticking a label on the front, and especially getting children to find something saying that they will not buy restricted books for their friends. I mean, I found that ridiculous. And I would have certainly found it ridiculous if I’d been asked to sign it as a child. And if I’d have signed it, I would at least have been clever enough to know that it didn’t mean a damn thing, because, as a minor, signing something, it’s just not worth the paper it’s printed on.

GROTH: Was that in the Buddy Saunders interview?

MOORE: No, but I believe it was in that issue of the Journal, that there was the actual form that parents have to sign...

GROTH: Yeah, I knew about the parents’ form.

MOORE: … that their children are allowed to buy from the other category. And at the bottom there was a subsection for the child himself or herself to sign, saying that they would not, if their parents had agreed that they could buy books rated 1 to 18, that they would not buy books for friends of theirs whose parents weren’t so lenient, which is just stupid. I mean, anybody who knows children and expects that to be binding is, I think, living in a fantasy world. All it’s going to do is just make people more furtive. I really don’t think, and if parents think that a rating system like that is going to stop children from seeing these books one way or another, then I think that they’re deluding themselves as well. So I would question that actual practical worth of the labeling system. I would also question the effect that it’s likely to have on the industry. I think that it would be a bad move for the industry and it would lead to a decline in standards.

GROTH: Are you talking about —

MOORE: Also, from my own personal point of view, as I said earlier, that I really do not think that we should restrict information to children. And I think that, basically, I know that there are a lot of parents that don’t agree, would not agree with me upon that, and of course they have the right, but as long as it’s kept upon a parental level, I’m not too worried. If parents are making the decisions that their children can or cannot read this sort of book in the home, that’s fair enough. The parents can take the consequences of that. It won’t necessarily stop the children reading it, but at least it’s a transaction between the child and the parent and it’s the parent taking responsibility for their children, which is fair enough. I take a more liberal stance in that I prefer to let my children read anything, but I want to know what they’re reading, and if there’s anything they come across which might be disturbing, then I’m always on hand to talk about it with them. Which, to me, seems to be the responsible attitude. What I object to is that there was, again, a mention in Buddy Saunders’s (or in the panel debate, or in the interview with Buddy Saunders, I can’t remember which), but there was a reference that, “We are aware that there are parents out there who can’t keep an eye on what their children are reading, and appreciate the help that we’re giving them in this.” And that’s where to me it starts to get sinister, the parents, I don’t care whether they can or whether they can’t, it’s their responsibility. They’re fucking parents. They shouldn’t hand over that responsibility to an outside body, and along with it, hand over the responsibility of all those other parents who have been finding it quite easy to take an actual personal interest in what their children are reading and to monitor their reading habits themselves.

GROTH: Well, let me ask you something that might ruffle your libertarian or anarchist feathers a little. Do you not think that there should be any kind of social or communal restraints on what children are permitted to buy? Because your argument presupposes that the parent will have followed his child or children everywhere they go until the time they turn 18.

MOORE: No. It doesn’t presuppose that at all, it presupposes that the parent will have established a basis of trust between himself and the children. I mean. I’m not going to follow my kids around. But I know that they’ve got nothing that they’re going to hide from me. Because there’s no reason to hide anything from me in terms of what they read. I’ve tried to establish a sensible relationship with my children, where there is mutual openness. Where they are allowed to exhaust their curiosity, and if they do, say for example, look at an issue of Zap Comics, because the color looks pretty, then I can say to them. “Yeah, well, there are a couple of stories in there which you might think were funny, but there’s also some stuff by S. Clay Wilson with men having their penises chopped off and it’s pretty horrible, and you can see all the veins in the middle, and you’ll probably find it a bit sickening, and you might not want to read it just before you go to bed.” In which case, they’ll either say, “Well. I think I’ll read it anyway.” or, more often than not they’ll say, “Well, in that case I’ll read something else” But if I said, “No, you can’t read it,” then that would probably mean that they would be sneaking into the bedroom in a week’s time, and looking at it. And then they wouldn’t be able to tell me that they’d looked at it, and they wouldn’t be able to discuss their reactions to it with me. That was the way I was brought up, Gary. You know, we weren’t allowed to mention that sort of stuff, so we did it anyway, and then coped with it ourselves. Which I don’t think is necessarily the most efficient way of doing it. So, in answer to your question, do I not think there should be any restraints on what children are sold, in terms of, well, I think that children have got as much rights as anybody else, and I think that —

GROTH: Well now wait a minute.

MOORE: — it should be left in the hands of the parents. Now, personally. I’ve got no objections to my children buying anything, as long as I know what it is, and as long as the relationship that we’ve got together, because I know that they’ll show me, that they won’t hide it from me, that I’ll be able to talk to them about it.

GROTH: Well now when you say that you think children have as many rights as anybody else, I mean, that’s not true. They can’t vote.

MOORE: It’s not, but I think that they should have.

GROTH: You think children should he able to vote?

MOORE: As far as I see it as a parent, there are some areas where I will take responsibility for the way my children live, I will tell them what to do. Like, “Don’t play in the traffic,” or “No, don’t go out and play in the street, because it’s getting too dark, and there are some funny people about.” I will still exert more authority upon children that otherwise I would not do upon other adults. So, yeah, you’ve got a point. When we decided to have children, we were taking responsibility for their upbringing, which is a high responsibility for anybody in that, a big and potentially dangerous thing, and we thought about it and we knew what we were doing. So, consequently, as long as I’ve got this relationship with my children, I will take responsibility for them in some areas. In every other area, I will try to encourage them to take as much responsibility upon themselves as possible. Including the choices of reading matter or listening matter or stuff like that. That is, as I see it, up to them. Now, other parents, who don’t have the same sort of slant on things as I do, if they don’t want their children to read certain stuff, then they can say to their children, “We don't want you reading books that have got pictures of naked ladies in them,” or “We don’t want you reading books that have got this amount of violence in it” or stuff like that.

That is what parents have to do. They have to tell their children these things, it’s part of the relationship between parents and children, and to deny that responsibility, to say, “No, we don’t want the trouble of getting into an argument with our children over what they can or cannot read, we’d rather that some outside third party took all this sort of stuff off of our hands and just refused to sell the kids the comics. Then that would solve our problems and we wouldn’t appear to be heavy-handed.” As far as I’m concerned, if parents want to stop their children reading certain things, then they should tell the children that and face the consequences. The feeling that I have is that the responsibility is the parent’s. If, as I have done, the parent then chooses to give as much of that responsibility to the child as he thinks the child can handle, that’s one thing. I find it’s very alarming and disturbing, the thought of handing it to outside bodies who would then be able to say that my children couldn’t read these things if they wanted to. It becomes a bit more problematic then. To me, everything’s fine as long as it’s parents imposing or not imposing, as long as parents are taking responsibility for their children, to the degree that they think is appropriate, then that seems to me to be perfectly fair and equitable. And it’s when it gets beyond that, that I start to find it alarming. As I say, I take an extreme stance, and I’m aware that it’s an extreme stance, but it still grows out of me taking responsibility for the children. It’s just that in some areas I try to give them as much responsibility and the freedom that comes with responsibility as I possibly can. It’s still a difficult abstract sort of moral point. [You can question whether there] should be any sort of material that children shouldn’t be allowed to buy. And you can say, what about those magazines with women being fucked by dogs, and stuff like that. I would always say that if parents have got a realistic relationship with their children, they would be able to tell children honestly about that sort of stuff, make them aware of what it was, and probably the children wouldn’t grow up with illicit burning desires for that sort of materials. To me, it seems that much more sensible, just total openness. I think that enables the child to make his own decision upon what he does and what he doesn’t want to read. I mean, my oldest daughter really, really likes Dark Knight, likes some bits of Maus, but found some of it boring, as she did with Watchmen. She thought some bits of that were boring.

GROTH: How old is your daughter?

MOORE: Nine. That’s the oldest. This was when she was eight.

GROTH: Right.

MOORE: Yeah, she might be an exceptional case. I don’t know, but she certainly was not disturbed by Dark Knight, and she’s read it four or five times. We can talk about all the bits in it. Anything that I think she might have had trouble assimilating, I can say, “What did you think of this scene?” It seems to me to be perfectly healthy. She is not reading it under the covers, she is not reading it behind my back, in case I shout at her. And the same goes for anything, I mean, there isn’t a thing which I will not discuss with her. Which I think is not the case with a lot of parents because a lot of parents are too embarrassed to discuss sexual matters or, indeed, anything pertaining to the real world with their children. And I don’t think we should encourage that sort of behavior by setting up outside bodies which encourages the parents to abandon all responsibility for their child’s reading and entertainment, because I think that does lead to a potentially threatening situation, where you have got restrictive bodies able to exercise their own prejudices upon children.

GROTH: So if you were a bookstore owner, you would have no qualms about selling children hard-core porn or anything that anybody would —

MOORE: Well, I certainly would have legal qualms. Gary.

GROTH: No, no. I meant moral.

MOORE: Moral. Well, obviously, I chose an extreme example there [pause]. And now I’ve got to defend it, haven’t I?

GROTH: [Laughs.] Yeah, right.

MOORE: All right. Well, there’s a certain level of common sense. If a child came into a bookstore that I was running and said, “Yes, I would like to buy this hardcore pornography,” I’d like to think that in a perfect world, I’d say, “Sure, sonny, have it, here it is.” Because I would know that they’ve got a good relationship with their parents and so on and so on, and it was something that they felt they were ready for. In practicality, I would perhaps, in an extreme case like that, say, “Well, maybe you could, if you really want this stuff, if you came back with your folks.” When I say “child,” I’m talking about somebody under the age of, say, 14. Well, 13 probably, I don’t know, I mean — if a fifteen-year-old came in the shop and asked for a copy of a porno magazine I’d sell it without any qualms at all. But if you’re talking about a seven-year-old...

GROTH: But there is a point—

MOORE: I don’t know. I might ask them to come back with their mother, you know. I know it sounds monstrous and perverted but it is an extreme example, and one I used, I suppose deliberately. But—

GROTH: But there is a point at which you would restrict the sale of material to children?

MOORE: There is a point where I would perhaps try to take precautions, and I can see that. You get into muddy areas when you talk, I realize that retailers do not want themselves to be busted, and I mean especially when you’re living in an area where the police are particularly heavy on that, or there are moral pressure groups, I can understand this is a very real fear for a person’s livelihood.

GROTH: No, no, no. I was disregarding any legal problems and I was just trying to probe the extent of your moral extremism.

MOORE: The extent of my moral … . Yeah, well, I suppose the extent of my moral extremism, when we’re talking into the vague, abstract sort of hypothetical cases, then, I meant to make a point, I can say, yes, I don’t believe that even hardcore pornography should be restricted to children. I would think that in reality there would be a certain sort of common sense element creeping in. I would try to handle it in as non-authoritarian a fashion as possible.

GROTH: Right, right. Would you have any qualms about porn shops advertising directly to children?

MOORE: Uhm …

GROTH: Would you governmentally restrict that?

MOORE: Well, if I had [qualms], I could protest in the ways that are open to me. I could write letters to the papers saying, “I would hope that all parents would be warning their children about this,” which would be legitimate, or I could protest in the ways that are open to me. But, in terms of sort of porn shops — mean, I’m getting a bit wary now, Gary, because having made such an extreme sort of example for meself, what can I say, it’s sort of … porn shops advertising to children, well … .

GROTH: I’m testing your libertarian principles, Alan.

MOORE: Yeah, you certainly are. Porn shops advertising to children, well...

GROTH: Considering the greed of the marketplace, I don’t see why you should preclude that possibility.

MOORE: I shouldn’t, really. I don’t feel any worse about that than I do about certain BB-gun manufacturers advertising to children, or the makers of, well, the war comics, or whatever advertising, from my personal view. I don’t like advertising of any sort, basically. I don’t want to defend people’s right to advertise, because I don’t like advertising, but in a hypothetical situation, then I don’t find anything more disagreeable in advertising pornography to children, than advertising cigarettes. I mean, I’m a smoker, I’m saying that children do notice cigarette adverts because they portray a view of what it’s like to be grown-up and manly, and I think it’s kidding ourselves if we say that those adverts only reach the adult audience that they are nominally intended for. Children see them. The same goes with liquor, or whatever. Advertising which children certainly see and perhaps do get the impression that this is how grown-up people behave, and if they want to be a grown-up, as a lot of children do, might see it as quite tantalizing. I think that our society does tend to have a very curious preoccupation with sex and hiding it. To me, these sort of talks always get into strange areas because of the predominance of sex in the discussion. That human sexuality seems to be the only real area of concern, which is something that I have a lot of trouble with. It’s always the sexuality that upsets these people. They can watch people having their brains smashed in one issue of Miracleman. They can watch people having their guts ripped out, and a human being blown into several pieces in one issue of Miracleman, and there will not be a word of complaint.

But the childbirth in the next issue will have them foaming at the mouth. There seems to be something wrong there. From my point of view, in terms of testing my libertarian principles, no, I would find it no more disturbing to have pornography advertised where children could see it and be affected by it than I do having most of the other facets of our glorious society advertised where children could be exposed to such advertisements. I’m somewhat dodging the issue, but I really don’t like advertising of any kind. But I don’t find the advertisement of pornography to be particularly disturbing when it’s right next to the advertising of, oh, Combat & Survival Magazine. All those other aspects are in their own ways different sorts of pornography. I don’t even find the advertising of pornography terribly insidious as far as children are concerned, when compared to the advertising of some of the ridiculous, yucky dolls that children are given to play with. In some instances, I think I would find the advertising of pornography less insidious to children than I would find the advertising for the Care Bears. I would hesitate to say which one would give a child a more destructive sort of social lesson.

GROTH: Right. Well—

MOORE: Does that answer your question. Gary? Without landing me in jail.

GROTH: Yeah. I think so, but let me just ask you if you don’t think you’ve relativized it to such a point that you would find nothing, whether it’s sex or violence, impermissible to advertise to children?

MOORE: Probably not. Like I say, you’re dealing with the wrong person. Gary, because I am extreme and cranky.

GROTH: [Laughter.] Uh-huh.

MOORE: I recognize this. I really don’t think that it would serve any point — well, I don’t like the idea of advertising. I’m not saying that people should advertise these things, but advertising is a part of our society, and will be until we find some way of getting rid of it. But given that, there’s already plenty of advertising for violence, or the accessories of violence, that is either aimed at children or is accessible to children, and one level, it could be argued that the person whom all the G.I. Joe merchandising is aimed at today is the person who’s going to grow up to be the person buying Soldier of Fortune tomorrow, and buying a rifle and heading for the library tower the next day. I mean, I don’t know how all that works, Gary, but I’d say there’s a case for saying that. But, if we’re going to have any sort of advertising, then, it strikes me as a bit bizarre and illogical to pretend that you can make the situation all right by banning the advertisements of particularly violent stuff to children or stuff like that. Because they see it anyway, they live in a completely violent world, and I think that when they’re reading the newspaper and seeing the news every day, they’re having real violence advertised to them in a way that’s much more, well, effective.

GROTH: Yeah, right.

MOORE: Sort of brutalizing — any sort of adverts of this stuff. All that I’m after, Gary, is honesty, basically. I mean, it does sound like I’m relativizing it out of existence, but—

GROTH: Yeah. I’m wondering if there are degrees of propagandizing directed toward children that society shouldn’t allow?

MOORE: I don’t know. As a parent, I already believe that there is vast amounts of propagandizing aimed at my children.

GROTH: Yeah, there is.

MOORE: So I try to create a relationship where I can make them aware of that. I think that going to assembly in the morning at school is a level of propagandizing that I personally would not choose if I were creating my model society. Because I’m personally not a Christian, and I resent the fact that my children were being forced into an acceptance of Christian icons and practices at school.

GROTH: Right, well we have that debate—

MOORE: As I’m sure that many of the Moral Majority would feel upset if their children were being brought up according to the way of Islam.

GROTH: Or even according to the Wizard of Oz.