The Crux of Binky Brown's Dilemma

The Crux of Binky Brown's Dilemma

In 1972 Justin Green sent me several copies of Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary and asked me to spread them around. He said he’d put nearly a year into this project but still wasn’t confident about whether it would be accepted. I recognized its originality and visual impact right away, and I wasn’t alone in my assessment that Green had just added a new genre to the comic medium – autobiography. Binky Brown represented both aberration and evolution.

It defied the traditions of a medium in which most cartoonists created fictional characters and stories, sometimes based on their actual experiences, but always at a remove. Details from their private lives were reserved for interviews and profiles, not for public consumption in the funny pages. Elzie Segar might draw upon his own nautical adventures to put wind in Popeye’s sails, or Al Capp might reflect on the realities of the cartoonist’s craft through Lester Gooch, the fictional Fearless Fosdick cartoonist. Occasionally cartoonists drew themselves in dialogue with their creations, but they would never confess to shameful secrets or dirty deeds. That would be akin to George Herriman describing how his own sexual predispositions affected Krazy Kat’s love triangle with Offisa Pup and Ignatz. That sort of thing could have had a negative effect on circulation.

It defied the traditions of a medium in which most cartoonists created fictional characters and stories, sometimes based on their actual experiences, but always at a remove. Details from their private lives were reserved for interviews and profiles, not for public consumption in the funny pages. Elzie Segar might draw upon his own nautical adventures to put wind in Popeye’s sails, or Al Capp might reflect on the realities of the cartoonist’s craft through Lester Gooch, the fictional Fearless Fosdick cartoonist. Occasionally cartoonists drew themselves in dialogue with their creations, but they would never confess to shameful secrets or dirty deeds. That would be akin to George Herriman describing how his own sexual predispositions affected Krazy Kat’s love triangle with Offisa Pup and Ignatz. That sort of thing could have had a negative effect on circulation.

Green challenged all of those cultural conventions with his first solo comic book. He was not the first or only cartoonist to place himself inside his strips, but he was the first to openly render his personal demons and emotional conflicts within the confines of a comic. Green spoke through a semi-fictional character named Brown, but this alter ego was as close to the bone as he could cut it. His compulsive habits and shameful moments take center stage in this theater of cruelty. Gags and plot lines play second banana, and props become weird fetish objects that transmit the artist’s anxiety. The work was created out of internal necessity, he insisted. Binky Brown’s tortured tale begins with the accidental destruction of a religious icon and ends with the deliberate destruction of many of them. In between, Green takes us on a tour of young Binky’s psychosexual development in a post-war middle class Midwestern suburb.

Most people prefer to deny their deep dark secrets, even from themselves, but Green gave us everything he’d stored up – angst, nausea, sexual humiliation, and morbid obsessions. He didn’t waste any time building up his ego or making himself look heroic. A girl he likes calls him an icky spaz. Two third-graders smash a cupcake on his head. He soils his shorts. He has homosexual thoughts about Christ, but through all his trials and tribulations he also manages to wrench loose a few yuks.

“I did a little research for a couple months prior to the book,” recounts Green. “On a card table I had almost a hundred little note cards as if I were doing a research paper in high school. These were all factual incidents or neurotic habits and so forth. I saw very early in the book that I would have to sacrifice the absolute journalistic truthfulness of some of these in order to weave a story. Virtually every incident in the book is allegorical, even though some have a closer foothold in reality. I’ll give you an example. I really did bang my head into the headboard every night. I probably did permanent brain damage. But on the other hand, I never had my ass kicked by two third-graders. But they both seem to fit. They’re both allegories in a sense because they are meant to suggest or convey a whole generalized idea about some subjective feeling, such as order or fear or guilt.”

“I did a little research for a couple months prior to the book,” recounts Green. “On a card table I had almost a hundred little note cards as if I were doing a research paper in high school. These were all factual incidents or neurotic habits and so forth. I saw very early in the book that I would have to sacrifice the absolute journalistic truthfulness of some of these in order to weave a story. Virtually every incident in the book is allegorical, even though some have a closer foothold in reality. I’ll give you an example. I really did bang my head into the headboard every night. I probably did permanent brain damage. But on the other hand, I never had my ass kicked by two third-graders. But they both seem to fit. They’re both allegories in a sense because they are meant to suggest or convey a whole generalized idea about some subjective feeling, such as order or fear or guilt.”

Binky wants to be a good boy, but even he can see how much more attractive lust and zealotry were. Yet he awkwardly attempts to synthesize conflicting credos, while also dealing with the raging distractions of puberty and in the throes of an undiagnosed case of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. His deck is stacked a little high.

“Humor is healing,” adds Green. “If you can laugh at absolutely any combination of images or any combination of taboo ideas, then I think that you’re healthy, or at least that you’re in the right direction. The Scientologists say that all humor comes from exclusion or embarrassment, but I think there is a third kind of laughter, which is the laughter of freedom. The laughter of sudden discovery that you’re suddenly above or beyond a conflict that once blocked you in.”

Ron Turner of Last Gasp Eco-Funnies paid Green a monthly stipend of $150 in advance royalties over seven months while he drew it. “I was three days over the deadline when I turned it in,” says Green. Within a month or two it was in print and being distributed in head shops and record stores across America and Western Europe.

The first ripple effects of this tour de force immediately spread to his contemporaries in the underground. Robert Crumb likewise laid bare his id in “The Confessions of R. Crumb” for The People’s Comics in that same year, and again with “The Adventures of R. Crumb Himself” for Tales of the Leather Nun the following year. So did Art Spiegelman, who began his family’s “Maus” saga in Funny Aminals (1972) and chronicled his mother’s suicide in “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” in Short Order Comix #1 (1973). It didn’t take much longer before many more artists came to believe that their own foibles were fair fodder for funnies and personal comics quickly proliferated.

While Green confessed and sought redemption, Robert Crumb, through his comic persona spoke directly to his readers to dispel myths, lay bare his sexual habits, and drive overeager fan away from adulation. “I’m abnormal, but I’ve been copping to it for so long that it no longer has any fear quotient for me at all,” he admits. “I got famous and over accepted. I got too much love. I had to make them back off by showing them this other side of myself – a real weirdness. And they did indeed back off.”

Art Spiegelman’s funny animal story, “Maus,” the first incarnation of his parents' life story starring Nazi cats and Jewish mice, began more like Roots, and eventually evolved into a two-volume epic tale when he began serializing the story in Raw magazine ten years later. “After I finished both those strips, ‘Hell Planet’ and ‘Maus’ I did have second thoughts about sending them off to be printed. I was a little bit concerned with it. Not enough to stop me,” he concedes.

“He was the FIRST, absolutely the FIRST EVER cartoonist to draw highly personal autobiographical comics,” insisted Robert Crumb on the back cover of the 1995 edition of the Binky Brown Sampler. “Binky started many other cartoonists along the same path, myself included. By me, he’s tops!”

“Without Binky Brown there would be no Maus,” added Art Spiegelman in the book’s introduction. “Justin helped me find my own autobiographical comix … by the example of his own work … I’ll never forget seeing the unpublished pages of Binky Brown hanging from a clothesline stretched around the drawing table and all through his living room back in 1971 and knowing I was seeing something new get born.”

Green appreciates the kudos but thinks he may have been miscredited. “It’s nice to have accolades, even if they are not quite true,” he wrote in the afterword to the 2009 deluxe edition of Binky Brown published by McSweeney’s Books. “Autobiography was a fait accompli, a low fruit ripe for the plucking. Binky’s story was contingent on my having seen the early work of other underground cartoonists. In addition to Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, I was also aware of Phillip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint and James. T. Farrell’s Studs Lonigan Trilogy. J.D. Salinger, too, was a hero from an early age. His Catcher in the Rye was a literary touchstone for my generation. I wasn’t surprised when I read in Dream Catcher, his eloquent daughter’s memoir, that he had a Jewish heritage and membership in the worldwide OCD club, too. Ironically, I have to give myself the one accolade I truly deserve: that Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary anticipated the groundswell in literature about obsessive compulsive disorder by almost two decades. If there was another description of this condition as a conscious work of literature, I wasn’t aware of it during the execution of Binky – and I have yet to see a precedent.”

It was the need to curb his compulsions that prodded him through the process more than a desire to augment the literary possibilities of sequential art.

My Life is an Open Book

Nevertheless, like an acorn that grows into a great oak, Green’s groundbreaking book yielded a bumper crop in subsequent generations of cartoonists who were similarly compelled to tell their own stories. Legions of practitioners all around the world have crafted a wide variety of autobiographix ranging from lurid confessions, intimate diaries, travelogues, braggadocio, family histories, crimes and misdemeanors, participatory journalism, exorcisms and secret desires, and as well as the trials and tribulations of the daily grind. Some cartoonists chose to speak through alter egos and others looked in the mirror for a model. Many of these plucky artists stand naked before their readers, admit to exuberance and excess, and own up to sexual peculiarities. Many say it’s liberating but most agree it’s still scary. It’s a tough row to hoe as an artist – cultivating raw material from your own experiences and presenting it in a way that’s both personal and universal. Many memoirists are miles apart in style or content but they all share a need to tell the world about themselves, and a desire to imbue their lives with meaning by elevating it to art, although it takes more than strong opinions or a list of grievances to tell a compelling story.

According to Dennis Eichhorn it also takes pith. In his introduction to Peter Kuper’s 1995 book Stripped, Eichhorn wrote, “It’s gotta be pithy. There’s got to be some tang, some substance, some pizzazz. Something to set it apart from the sub-standard, self-concerned pap that is continually churned out by legions of autbio wanna-bees. Something unique.”

According to Dennis Eichhorn it also takes pith. In his introduction to Peter Kuper’s 1995 book Stripped, Eichhorn wrote, “It’s gotta be pithy. There’s got to be some tang, some substance, some pizzazz. Something to set it apart from the sub-standard, self-concerned pap that is continually churned out by legions of autbio wanna-bees. Something unique.”

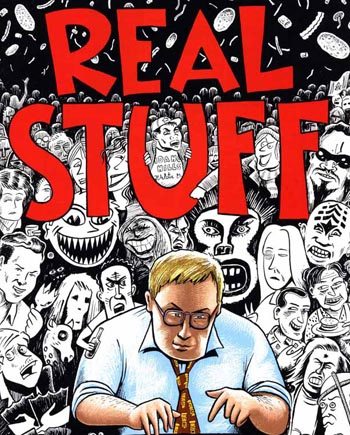

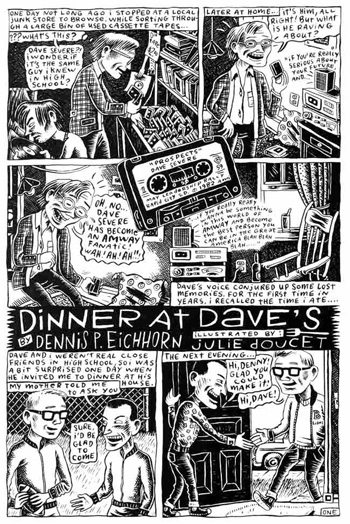

During the 1990s Eichhorn beat the pith out of his own life in Real Stuff and Real Smut comics. He wrote the scripts, but since he didn’t draw, he recruited his favorite cartoonists to illustrate his stories of brawls, binges, and bimbos, mostly dredged from his misspent youth, but also from his post-LSD evolution. He drew his inspiration from cartoonists and collaborators who were making their own forays into autobiography.

“Robert Crumb has done a lot of autobio, and he's terrific,” says Eichhorn. “His artwork is unsurpassed, and he's got a strong, honest, clear voice. People tend to overlook what a good writer he is. Mary Fleener is another gifted artist and writer, and I admire her honesty, especially about sexual hi-jinx. Joe Matt is fabulous, self-deprecating and funny. Joe Sacco is a great artist, plus he's tremendously brave. I like Bob Crabb's work, too. Aline Kominsky-Crumb is a good writer, although she shies away from explicit sex scenes (unlike her hubby); really, few writer/artists, especially women, go ‘all the way’ with depictions of penetration and kinky sex. But outside of that, Aline has a direct, straightforward delivery that is enjoyable to read, and her artwork has steadily improved over the years. Her dialogue is very tight, and oftentimes funny. She's the real deal. I've heard people criticize her, and say she wouldn't be as widely published as she is were it not for her association with Crumb; I say, 'So what?' It is what it is. Others are David Collier, Seth, Howard Chackowicz, Dori Seda...the list would be long, if it were to be complete. They all have their special attributes and strong points. One of my personal favorites is Eve Gilbert, who wrote and drew Tits, Ass & Real Estate. She's a pithy writer, but her artwork isn't as accomplished as some of the others cited above. Her work is a good example of the truism that a good story trumps artwork. Of course, if you've got both, you've got something special.”

Eichhorn was born in a women’s prison and adopted by a Boise couple when he was just a few days old. His new parents didn’t mention it to him until thirty years later. “One day I took some LSD with my wife and we were sitting around the house," he says. "We were just starting to get off when the phone rang. It was my adopted mom and she says ‘I’ve wanted to tell you this for years. You were born in a women’s prison in Deer Lodge, Montana and we adopted you.’ She told me what my real name was. I told her thanks and we should talk about it sometime. My wife comes back into the room and I said, “That is good LSD. I just hallucinated that my mother called and said I was adopted.”

Eichhorn always enjoyed telling people about his escapades during his high school and college years in Idaho, his bartending nights in California, and his newspaper days in Seattle. He was working as an editor at The Rocket when cartoonist Carel Moiseiwitsch asked him if she could draw a comic strip from a story he told her about a prostitute who gave him a blow job and then killed herself the next day, which became “The Fatal Fellatio.”

“About the same time Seattle artist Michael Dougan offered to draw a story that I told him about being jailed for drug dealing, and we came up with ‘Dennis the Sullen Menace’. In both cases, the artists were the instigators, and both products were superior work," remembers Eichhorn. "And then it just sort of took off. I always had stories that I would tell to people, and when I got the chance to adapt them to a graphic, sequential format, I did so. By the time we did two or three issues I had people contacting me all the time offering to do stories. Some were fledgling and others were well known. It got to where whenever I would meet somebody that was a cartoonist the subject would come up and about half the time they’d say they would want to do it. For me, it was a cathartic experience. Once these stories are converted to comix, I rarely think of them or tell them orally again.”

“About the same time Seattle artist Michael Dougan offered to draw a story that I told him about being jailed for drug dealing, and we came up with ‘Dennis the Sullen Menace’. In both cases, the artists were the instigators, and both products were superior work," remembers Eichhorn. "And then it just sort of took off. I always had stories that I would tell to people, and when I got the chance to adapt them to a graphic, sequential format, I did so. By the time we did two or three issues I had people contacting me all the time offering to do stories. Some were fledgling and others were well known. It got to where whenever I would meet somebody that was a cartoonist the subject would come up and about half the time they’d say they would want to do it. For me, it was a cathartic experience. Once these stories are converted to comix, I rarely think of them or tell them orally again.”

The majority of his autobiographic tales involve drinking, drugs, fighting and fucking, not always in that order, but usually in some combination of the above. If those things happened as frequently as his body of work suggests, he’d be lucky to still be alive. In reality, the stories he wrote were distillations of brief but dramatic moments during fifty years of living, working and traveling. There were plenty of dull moments as well, he avowed, but in his art it was more exciting to highlight Dennis the Sullen Menace.

Real Stuff stands out in sharp contrast to another autobiographical comics series, American Splendor, written by Harvey Pekar, whose long career as a file clerk for the Veteran’s Administration formed the center of his comic world, supplemented with monotonous domestic chores, meandering internal dialogs, encounters with nerds and schlemiels, and tedious accounts of his appearances on David Letterman’s show.

Some people prefer to read about the banality of everyday life instead of its frenetic moments, says Eichhorn. “I didn't get bored by Harvey Pekar's work, but I've heard people make that comment. He just used the medium in a different way than I did. Our work doesn't have much in common, except the superficiality of both being crafted in sequential illustrative form. Harvey's work got instant recognition because Robert Crumb drew some of his early stories. Then other artists were anxious to work with him. Harvey favored realists, and closely oversaw their work. I worked with all sorts of artists, and didn't nitpick with most. Sometimes that backfired badly, and after a while I found a workable middle road. Some artists are capable of working with minimal input; others require more hands-on guidance. I tried to work with the artists' strengths. Harvey also owned the work product entirely. I've always shared copyright ownership with the creators I work with, and they own the actual physical renditions.”

Eichhorn’s scripts read like short films, as in the first act below.

TOPSY-TURVY

By Dennis P. Eichhorn

(Caption at top of panel:) When I was in high school, there was a wild rumor floating around town...

(High school-age kid telling me:) "Did you hear what Jack Kaper did?"

(Me, answering:) "No, what?"

(Kid:) "He fucked a girl who was standing on her head!"

(Me, visualizing an improbable scenario of Jack Kaper fucking a girl who is standing on her head)

(Caption at bottom of panel:) That was hard to believe!

(Caption at top of panel:) As time passed, I became obsessed with duplicating Kaper's sexual feat!

(I'm naked with a girl in bed, and she says:) "So, Denny, is there anything special you'd like to do?"

("Me, answering:) "Well, yes, Eleanor, there is..."

(Small inset of me whispering in Eleanor's ear, as she registers outrage:) "pssst, pssst..."

(Small inset of her hand hitting my face:) "SLAP!"

(Eleanor angrily says:) "What do you think I am, some kind of perverted acrobat?"

(Me, rubbing my cheek, pain radiating from it, answering:) "One can only hope."

Pekar’s “scripts” were often just a page or two of tiny, penciled panels dominated by speech balloons, with little stick figures in the narrow space beneath each text block. Mary Fleener, a California cartoonist who has drawn for both writers, was glad to work with Pekar but preferred the Eichhorn approach to comic writing. “Denny would give me his script, but I didn’t have to follow it in the least," she says. "I think Real Stuff was as important as Weirdo, historically speaking. He used really good artists and the wackier, the better.”

Pekar brought an interesting sensibility to his comic stories, she adds. “I got into his writing because he is so obsessive about everything and uses thought balloons so much, you really know what’s going on inside his head, and I found I could relate to his constant over-analysis of things, and to be sure, he’s a cheap bastid, and takes advantage of people, but what makes you care about the character is when cornered, he does come around and is remorseful about his behavior. It’s a lonely guy book, which is why I think a lot of people like it. I also liked how he writes in that East Coast dialect … it’s whole other woild!”

But she wasn’t impressed with the script he sent her to illustrate about Beat poet Diane di Prima. “When I got Pekar’s meager script for The Beats book, it was pathetic. I was excited to be doing something with him, and I get this? I was expected to do four pages and all I got were eight paragraphs, full of mistakes and not very interesting.” She spent the next year doing her own research and rewriting the story. The final disappointment came when she was told after handing in her artwork that it was work for hire.