2012: there weren't a lot of great comics, but there were a few, and there were quite a lot of really good comics. Very, very few of them came out of left field, which is to be expected--the internet certainly blesses us with access to new talent, but it can't create new talent, and the years up until 2012 were so overstuffed that we had to hit the repeat part of the cycle eventually. That's a good thing too. Having the time to process the last few years of Kate Beatons (the original was last seen in the Economist, by the way, if you want to get real with it) and DeForges has been a much lusted for moment, and in between the expected knockout punches from big dogs like Ware and Gilbert, that processing was finally had. It didn't hurt that Marvel and DC spent the majority of the year reverting to what they do best--try to fuck each other out of every available dollar imaginable--because that left the rest of comics to play with their own obsessions without having to reassure the superhero guys every couple of minutes that we see what you're doing over there, and yes we are very very proud of how much better you are at doing it. (That being said, Grant Morrison's Batman Incorporated was as good as anything he's ever done, and Ed Brubaker's Winter Soldier was so gleeful it made the rest of Marvel's output seem like they had been written by that Orin character from Parks and Recreation. And honestly, as bad as it got at the Big Two, nobody stunk up the room like The New Yorker, who had the taste to print multiple excellent covers--Tomine's ironwilled comment on post-Sandy NY, Ware's "Back To School"--and yet showed zero inclination to bring that sort of work into the rest of the magazine, choosing instead to pump out the sort of cartooning you'd expect to find in a Reader's Digest for coma patients.)

That aside, it's hard to get too critical when there's this many great comics immediately in the rear view. Here's to them, and here they are.

19: Eat More Bikes, by Nathan Bulmer.

I first discovered Nate's comics when I came across them at the bottom of a box I was trying to empty, and while what I found--a minicomic containing the adventures of Dwight Dangle, PI--didn't seem to be setting the world on fire, what I started to see every day at his website, certainly had that level of potential. Bulmer's comics are surprising and occasionally gross, but most of all, they're really, really funny. In case his inclusion in the last 20-odd columns haven't made it clear, here he is again, right where he belongs: at the top of the fold, flaunting his wares like the trollop he is.

I first discovered Nate's comics when I came across them at the bottom of a box I was trying to empty, and while what I found--a minicomic containing the adventures of Dwight Dangle, PI--didn't seem to be setting the world on fire, what I started to see every day at his website, certainly had that level of potential. Bulmer's comics are surprising and occasionally gross, but most of all, they're really, really funny. In case his inclusion in the last 20-odd columns haven't made it clear, here he is again, right where he belongs: at the top of the fold, flaunting his wares like the trollop he is.

18: Prison Pit Book Four, by Johnny Ryan.

There's no surprises left in this series besides what Ryan chooses to do with the plot, and while that definitely limits the levels on which Prison Pit can work on its audience--it's hard to explain how intense the surprise was for a follower of Angry Youth and Ryan's humiliation comics to open that first Prison Pit (that experience is impossible to repeat, short of Ryan going the other direction entirely and writing chaste Spider-Man scripts for Eddie Barrows to draw)--it doesn't take away from the ease with which this volume delivers. We're supposedly nearer the conclusion then we are the beginning, but you could've fooled me.

There's no surprises left in this series besides what Ryan chooses to do with the plot, and while that definitely limits the levels on which Prison Pit can work on its audience--it's hard to explain how intense the surprise was for a follower of Angry Youth and Ryan's humiliation comics to open that first Prison Pit (that experience is impossible to repeat, short of Ryan going the other direction entirely and writing chaste Spider-Man scripts for Eddie Barrows to draw)--it doesn't take away from the ease with which this volume delivers. We're supposedly nearer the conclusion then we are the beginning, but you could've fooled me.

17. Dungeon Quest Book Three, by Joe Daly.

"Just a bunch of dick jokes"--this is what boring clowns say, and they say it so that you and I and all the people in our lives who we want to keep there will know to steer clear of them, because while dick jokes aren't for everyone, the kinds of people who want to cleanse the world of dick jokes are also the kinds of people who want you to wear cargo shorts to an "adults only" tea party, and it's "adults only" not because of some cool orgy reason, but because "children don't know how to do a tea party correctly because they are so terrible, these children, they eat all the cookies and they can't do accents well at all." It's like that old free speech conundrum: you want to defend it, but nobody wants to listen to Body Count; Body Count was a terrible, terrible fucking band. But in times like these, with sandwiches like mine, you have to root for the one who brung you, and that's dick jokes. Dungeon Quest had so many of them, and they were all wonderful.

"Just a bunch of dick jokes"--this is what boring clowns say, and they say it so that you and I and all the people in our lives who we want to keep there will know to steer clear of them, because while dick jokes aren't for everyone, the kinds of people who want to cleanse the world of dick jokes are also the kinds of people who want you to wear cargo shorts to an "adults only" tea party, and it's "adults only" not because of some cool orgy reason, but because "children don't know how to do a tea party correctly because they are so terrible, these children, they eat all the cookies and they can't do accents well at all." It's like that old free speech conundrum: you want to defend it, but nobody wants to listen to Body Count; Body Count was a terrible, terrible fucking band. But in times like these, with sandwiches like mine, you have to root for the one who brung you, and that's dick jokes. Dungeon Quest had so many of them, and they were all wonderful.

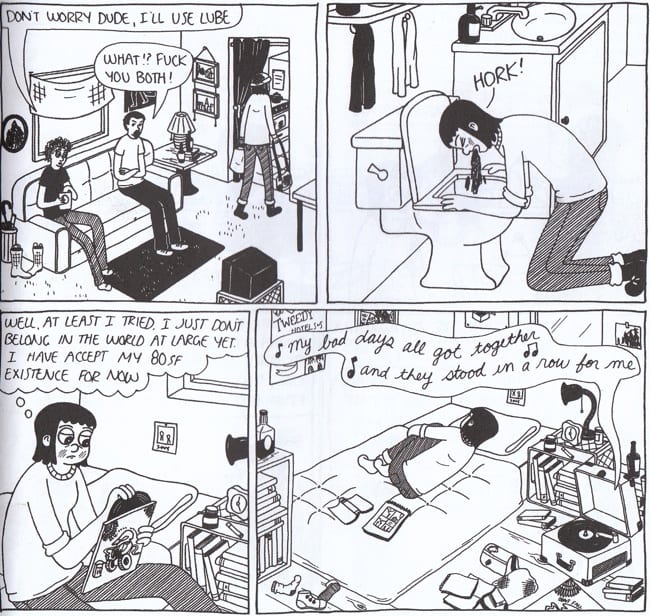

16. The Infinite Wait, by Julia Wertz.

Oh, I loved this book, I love it more as time goes on. Wertz is such a bizarre cartoonist, at least to my eyes. It's sneaky comics, with emotions and adverbs written into the interchangeable faces, screwed into the Playskool bodies that prop them up. You'll figure out that a pizza manager is a creep even before your eyes explain that he's a male, and it'll take days to remember that he's really just a bunch of lines and a circle. All this dialog, this pointless self-hate and I'm-way-ahead of you shit--none of it should work this well, it should alienate at the very least, and yet the opposite happens every time. Excellent work, and a brilliant primer on why everybody steals from her when they want to be funny.

Oh, I loved this book, I love it more as time goes on. Wertz is such a bizarre cartoonist, at least to my eyes. It's sneaky comics, with emotions and adverbs written into the interchangeable faces, screwed into the Playskool bodies that prop them up. You'll figure out that a pizza manager is a creep even before your eyes explain that he's a male, and it'll take days to remember that he's really just a bunch of lines and a circle. All this dialog, this pointless self-hate and I'm-way-ahead of you shit--none of it should work this well, it should alienate at the very least, and yet the opposite happens every time. Excellent work, and a brilliant primer on why everybody steals from her when they want to be funny.

15. Grandville Bete Noire, by Bryan Talbot.

Possessing the finest line of dialog of any comic 2012 had to offer--that would be "By Timothy! I'm totally flummoxed. It's a bit of a puzzler, what?"--and resting a key scene on a Bondian gadget being set off by an all-time-great sight gag, Grandville Bete Noire disembowels expectations, fills the innards with custard, and then sprays them into its audience's delighted mouths. If you're one of the rare people who can't get a laugh out of this one, then at least keep it around. Use it as a one-volume encyclopedia of every available type of humor comics can provide.

Possessing the finest line of dialog of any comic 2012 had to offer--that would be "By Timothy! I'm totally flummoxed. It's a bit of a puzzler, what?"--and resting a key scene on a Bondian gadget being set off by an all-time-great sight gag, Grandville Bete Noire disembowels expectations, fills the innards with custard, and then sprays them into its audience's delighted mouths. If you're one of the rare people who can't get a laugh out of this one, then at least keep it around. Use it as a one-volume encyclopedia of every available type of humor comics can provide.

14. Prophet, by Brandon Graham, Simon Roy, Farel Dalrymple, Joseph Bergin III, Giannis Milonogiannis & Richard Ballerman.

Convoluted in all the right ways, the Prophet series, written by Brandon Graham and drawn by a core group of talented artists, started off as the comic a whole lot of people wanted to like (because it seemed like such a good idea on paper) but few of us really expected to (because it's an Image comic, and the only people who like Image comics are people who want to make their own Image comic). And then, in a matter of essentially no time at all, the comic turned out to be more than a little bit interesting. As of this writing, 12 issues have been released--of those, 11 came out in 2012--and each issue is as exciting as the previous one, and there's no sign of wear yet. This is the one to steal from, if that's the business you're in.

Convoluted in all the right ways, the Prophet series, written by Brandon Graham and drawn by a core group of talented artists, started off as the comic a whole lot of people wanted to like (because it seemed like such a good idea on paper) but few of us really expected to (because it's an Image comic, and the only people who like Image comics are people who want to make their own Image comic). And then, in a matter of essentially no time at all, the comic turned out to be more than a little bit interesting. As of this writing, 12 issues have been released--of those, 11 came out in 2012--and each issue is as exciting as the previous one, and there's no sign of wear yet. This is the one to steal from, if that's the business you're in.

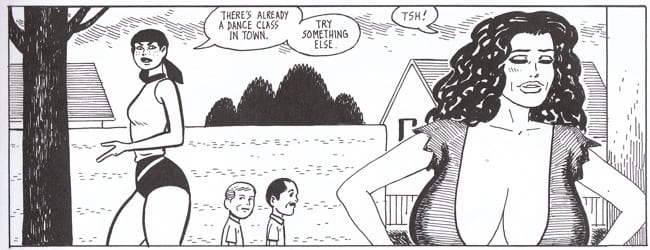

13. Love and Rockets New Stories Volume 5, by The Hernandez Brothers.

No comic is as great an example of the nature of 2012's predictability as Love and Rockets, and no volume suffered as much from expectation as this specific volume. It was great, and of course it was, because it's them, and it was great for all the same reasons you'd expect it to be, and while it lacked the double album wall-of-speakers grandeur of last year's installment (or 2010's "Browntown", for that matter), that wasn't a surprise either: Jaime had resolved his one major 30-year-old open loop, and there aren't a lot of those available. And that's how it was for a lot of comics this year--you got what you expected, or something wearing the thing that you expected's clothes. The difference here was that it's the Hernandez Brothers. When they sit around the house ... you get the drift.

No comic is as great an example of the nature of 2012's predictability as Love and Rockets, and no volume suffered as much from expectation as this specific volume. It was great, and of course it was, because it's them, and it was great for all the same reasons you'd expect it to be, and while it lacked the double album wall-of-speakers grandeur of last year's installment (or 2010's "Browntown", for that matter), that wasn't a surprise either: Jaime had resolved his one major 30-year-old open loop, and there aren't a lot of those available. And that's how it was for a lot of comics this year--you got what you expected, or something wearing the thing that you expected's clothes. The difference here was that it's the Hernandez Brothers. When they sit around the house ... you get the drift.

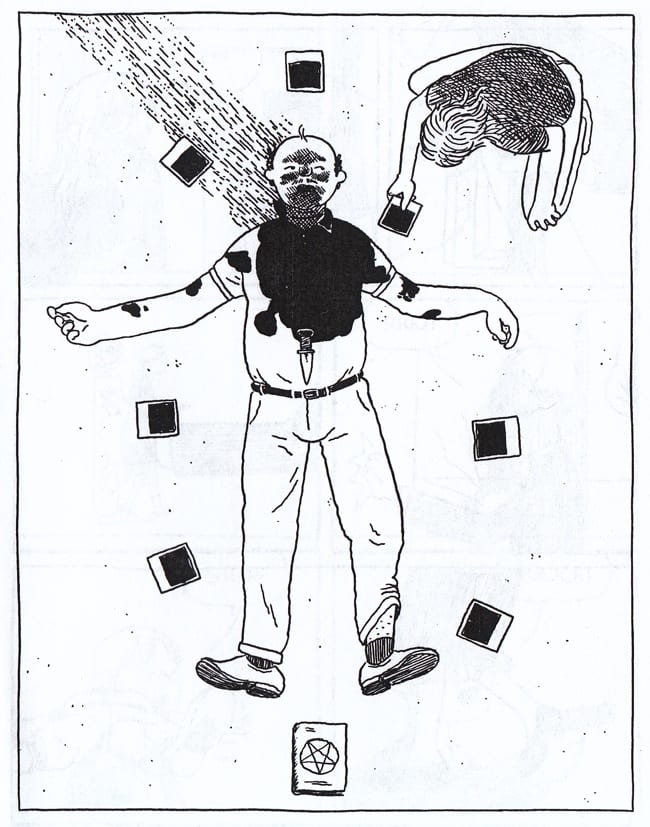

12. Lincoln Washington Free Man, by Benjamin Marra.

I liked Django Unchained fine, but if I had to pick a single slavery revenge fantasy out of obligation to some kind of idiotic thought experiment devised primarily as an engine for exaggeration, it would be Lincoln Washington, and not just because it's shorter and therefore gets to the point a lot quicker. Those are the primary reasons that I like it more than Django, although they aren't the only ones. I also like it because it was the comic that finally got Benjamin Marra some negative reviews, and while the capital-I Importance of those negative reviews eventually went a little far past their actual arguments, it cemented Marra as being more than just a flavor-of-the-blogs cartoonist, existing so that his fans (and friends) can praise him. You're nobody until somebody hates you, and if you don't believe that ... well, enjoy your cute little hobby, kid. Going pro takes a thicker skin.

I liked Django Unchained fine, but if I had to pick a single slavery revenge fantasy out of obligation to some kind of idiotic thought experiment devised primarily as an engine for exaggeration, it would be Lincoln Washington, and not just because it's shorter and therefore gets to the point a lot quicker. Those are the primary reasons that I like it more than Django, although they aren't the only ones. I also like it because it was the comic that finally got Benjamin Marra some negative reviews, and while the capital-I Importance of those negative reviews eventually went a little far past their actual arguments, it cemented Marra as being more than just a flavor-of-the-blogs cartoonist, existing so that his fans (and friends) can praise him. You're nobody until somebody hates you, and if you don't believe that ... well, enjoy your cute little hobby, kid. Going pro takes a thicker skin.

11. Crossed: Badlands #1-3, by Garth Ennis & Jacen Burrows.

For the glory of a paycheck and the challenge of resuscitating a franchise, Garth Ennis delivered a disgusting thought experiment that saw him confronting ... religion? Something to do with British royalty? The comics industry's barely concealed distaste for Robert Kirkman? The challenge of reading Badlands wasn't limited to its more unsavory content, but to the brutish zealotry with which Ennis and Burrows hacked away at empathy fantasies, showcasing extermination as a thing not to lust after, but to be wholly terrified by, body and soul. If the movie does it right, you aren't supposed to want to live in the mall at the end. Survival is supposed to mean a whole lot more than staying alive.

For the glory of a paycheck and the challenge of resuscitating a franchise, Garth Ennis delivered a disgusting thought experiment that saw him confronting ... religion? Something to do with British royalty? The comics industry's barely concealed distaste for Robert Kirkman? The challenge of reading Badlands wasn't limited to its more unsavory content, but to the brutish zealotry with which Ennis and Burrows hacked away at empathy fantasies, showcasing extermination as a thing not to lust after, but to be wholly terrified by, body and soul. If the movie does it right, you aren't supposed to want to live in the mall at the end. Survival is supposed to mean a whole lot more than staying alive.

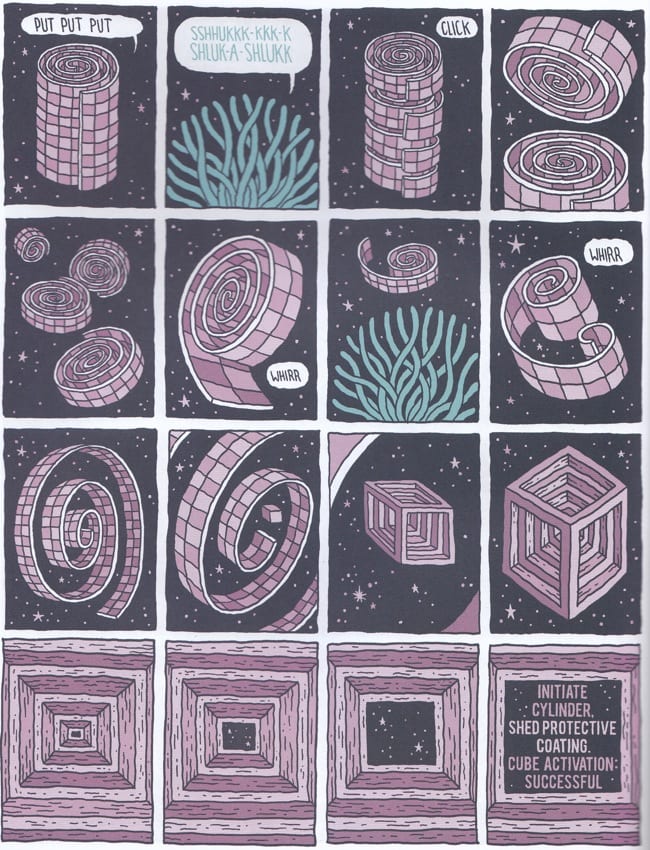

10. By This Shall You Know Him, by Jesse Jacobs.

Answering the oft-pondered question of what M.C. Escher would have been like if he had been born a girl who was then hired by Michael DeForge to do storyboards for the Adventure Time cartoon, By This Shall You Know Him is so post-comics it had to get Biblical just so us early-30's types can have a reference point we understand. This is the best thing you didn't read, friend.

Answering the oft-pondered question of what M.C. Escher would have been like if he had been born a girl who was then hired by Michael DeForge to do storyboards for the Adventure Time cartoon, By This Shall You Know Him is so post-comics it had to get Biblical just so us early-30's types can have a reference point we understand. This is the best thing you didn't read, friend.

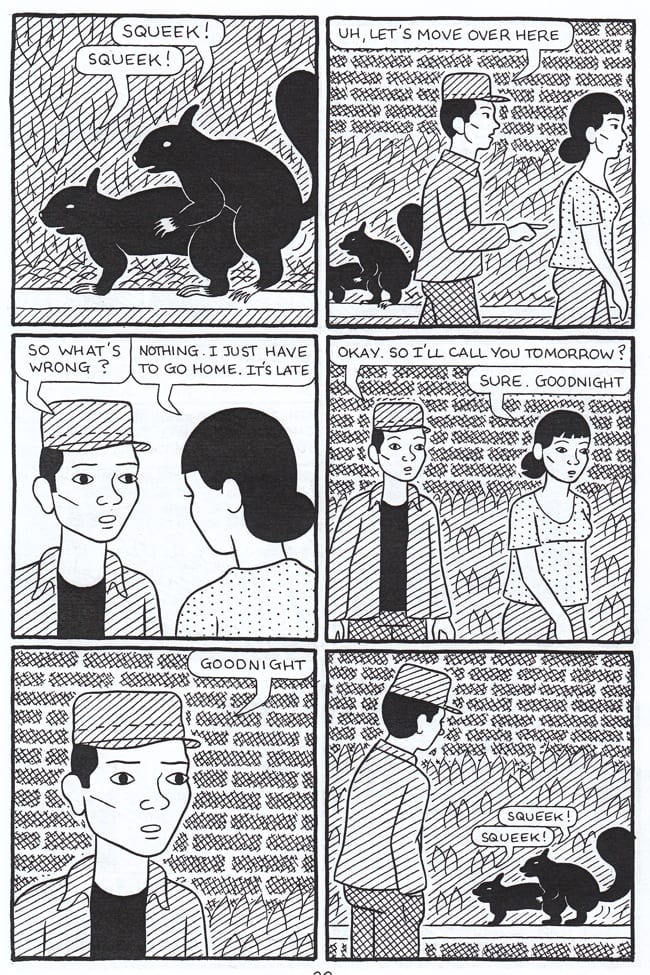

9. The End of the Fucking World, by Chuck Forsman.

2012's most consistent ongoing series was also its comic in most need of a better superlative--if there's one race it's easy to win, it's the one where your competition includes things by Jonathan Hickman. Chuck Forsman, a workhorse cartoonist & red-blooded auteur turned aw-shucks entrepreneur, remains the only stripped-down no-bullshit cartoonist capable of churning out comics without them seeming the least bit ... well, churned, actually. Tumblr, your sister's Risograph, and your personal response to Thickness: we get it, 2012. You can make a lot of comics. Here's a plea: unless your mama's name is Mrs. Forsman, we probably don't need to look at them.

2012's most consistent ongoing series was also its comic in most need of a better superlative--if there's one race it's easy to win, it's the one where your competition includes things by Jonathan Hickman. Chuck Forsman, a workhorse cartoonist & red-blooded auteur turned aw-shucks entrepreneur, remains the only stripped-down no-bullshit cartoonist capable of churning out comics without them seeming the least bit ... well, churned, actually. Tumblr, your sister's Risograph, and your personal response to Thickness: we get it, 2012. You can make a lot of comics. Here's a plea: unless your mama's name is Mrs. Forsman, we probably don't need to look at them.

8. Lose #4, by Michael Deforge.

At one point, the big story with DeForge this year seemed like it was going to be about the comics he wasn't making--namely, the Open Country series, which he abandoned for the best reason of all time: personal dislike--but then came Lose 4, a beast of an issue, and like every issue of Lose before it, the conversation immediately reverted to who-the-fuck-is-this-guy once again. Exciting, lurid work from a brilliant cartoonist whose biggest flaw remains his absurd country of origin. Canada: you remain the absolute worst.

At one point, the big story with DeForge this year seemed like it was going to be about the comics he wasn't making--namely, the Open Country series, which he abandoned for the best reason of all time: personal dislike--but then came Lose 4, a beast of an issue, and like every issue of Lose before it, the conversation immediately reverted to who-the-fuck-is-this-guy once again. Exciting, lurid work from a brilliant cartoonist whose biggest flaw remains his absurd country of origin. Canada: you remain the absolute worst.

7. Building Stories, by Chris Ware.

There were some excellent comics here, one terrible one, and a couple of folded pieces of paper that don't require a value judgment. Taken as a whole, Building Stories provided the most immersive character study outside of Proust (which also makes it the only good one, because fuck that mother-obsessed cork-lined sociopath), with passages on parenthood that would eliminate every criticism of solipsistic self-loathing ever leveled against Ware ... that is, if any of those bitches had what it took to actually read the guy. That being said: this format was silly as hell.

There were some excellent comics here, one terrible one, and a couple of folded pieces of paper that don't require a value judgment. Taken as a whole, Building Stories provided the most immersive character study outside of Proust (which also makes it the only good one, because fuck that mother-obsessed cork-lined sociopath), with passages on parenthood that would eliminate every criticism of solipsistic self-loathing ever leveled against Ware ... that is, if any of those bitches had what it took to actually read the guy. That being said: this format was silly as hell.

6. The Libertarian, by Nick Maandag.

There's a million--no, two million--paper-folded-in-half black & white minicomics published every 17 minutes, and if we all took our own lives tonight, not a single one of those minicomics would flash before our eyes as the saber cleaves us in twain. That is, unless we're talking about Nick Maandag's The Libertarian, which was hands down the funniest comic (and one of the funniest things in general) of the year. It's enough to make me say You Guys, you guys. You Guys!

There's a million--no, two million--paper-folded-in-half black & white minicomics published every 17 minutes, and if we all took our own lives tonight, not a single one of those minicomics would flash before our eyes as the saber cleaves us in twain. That is, unless we're talking about Nick Maandag's The Libertarian, which was hands down the funniest comic (and one of the funniest things in general) of the year. It's enough to make me say You Guys, you guys. You Guys!

5. Deathzone, Copra, & Zegas, by Michel Fiffe.

While most of 2012's out-of-work cartoonists preferred to sit around and explain that the world is basically composed of cheap assholes who don't recognize their genius right before they prostitute themselves so cheaply that they add a Sophie's Choice level to the "mouths to feed" argument, Michel Fiffe--a guy who made so little money over the last ten years of making comics that it would've been more financially beneficial to get day drunk and steal some copper wire--managed to produce four full-length comic books, sell a shit load of them, garner the admiration of people with taste, and still alienate those in the "community" whose only saving grace seems to be the inability to take the fucking hint, the hint being that they should go somewhere cold, so that they could die.

While most of 2012's out-of-work cartoonists preferred to sit around and explain that the world is basically composed of cheap assholes who don't recognize their genius right before they prostitute themselves so cheaply that they add a Sophie's Choice level to the "mouths to feed" argument, Michel Fiffe--a guy who made so little money over the last ten years of making comics that it would've been more financially beneficial to get day drunk and steal some copper wire--managed to produce four full-length comic books, sell a shit load of them, garner the admiration of people with taste, and still alienate those in the "community" whose only saving grace seems to be the inability to take the fucking hint, the hint being that they should go somewhere cold, so that they could die.

4. My Friend Dahmer, by Derf Backderf.

A historical study of a serial killer's youth that doubles as sociological treatise, My Friend Dahmer is so much more intelligent then the terrible, terrible comics it shares categorization with that it would almost be better if it didn't exist. If this is the bar that true crime has to meet, then true crime is completely and utterly fucked.

A historical study of a serial killer's youth that doubles as sociological treatise, My Friend Dahmer is so much more intelligent then the terrible, terrible comics it shares categorization with that it would almost be better if it didn't exist. If this is the bar that true crime has to meet, then true crime is completely and utterly fucked.

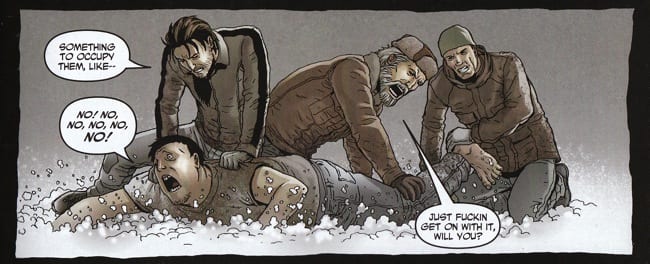

3. B.P.R.D. Hell on Earth: The Long Death, by Mike Mignola, John Arcudi, James Harren & Dave Stewart.

One of the few great serialized comics of the last twenty years spent most of 2012 pissing its luster down the drain with a series of decisions so progressively bad that one wonders if Mike Mignola might have suffered an undiagnosed cerebral hemorrhage, but before doing so, James Harren--a young artist who somehow managed to have a Deviant Art page without becoming either a racist or a sex criminal--turned out the most dynamic and bizarre series of fight comics outside of Japan, where they probably publish crazy shit like this all the time. The story, which won't make sense to you unless you read the B.P.R.D. regularly, and if that's the case, you won't need me to tell you what it is, consisted mostly of supergroup power chords, with the series three scene-stealingist characters brutalizing one an other for 60-odd pages. You can't make a menu out of these kinds of comics, but you can create one epic memory of a meal.

One of the few great serialized comics of the last twenty years spent most of 2012 pissing its luster down the drain with a series of decisions so progressively bad that one wonders if Mike Mignola might have suffered an undiagnosed cerebral hemorrhage, but before doing so, James Harren--a young artist who somehow managed to have a Deviant Art page without becoming either a racist or a sex criminal--turned out the most dynamic and bizarre series of fight comics outside of Japan, where they probably publish crazy shit like this all the time. The story, which won't make sense to you unless you read the B.P.R.D. regularly, and if that's the case, you won't need me to tell you what it is, consisted mostly of supergroup power chords, with the series three scene-stealingist characters brutalizing one an other for 60-odd pages. You can't make a menu out of these kinds of comics, but you can create one epic memory of a meal.

2. Fury: My War Gone By, by Garth Ennis, Goran Parlov & Lee Loughridge.

No surprises here. Garth Ennis does war comics better than most people are capable of doing laundry, Goran Parlov and Lee Loughridge razor together pulp boy's adventure and trashbucket black noir sleaze. A lot of credit for that series goes to Ellroy's Underworld Trilogy, a debt that Ennis is happy to acknowledge, but don't come in expecting bullet point sentences--there's meat, moist and hot, on every single page. Garth Ennis: welcome back.

No surprises here. Garth Ennis does war comics better than most people are capable of doing laundry, Goran Parlov and Lee Loughridge razor together pulp boy's adventure and trashbucket black noir sleaze. A lot of credit for that series goes to Ellroy's Underworld Trilogy, a debt that Ennis is happy to acknowledge, but don't come in expecting bullet point sentences--there's meat, moist and hot, on every single page. Garth Ennis: welcome back.

1. Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller, by Joseph Lambert.

My first impulse after reading Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller was to find out who had helped Joe Lambert make the comic. Initially, I chalked that up to my hyperactive cynicism and every ugly part of my personality, each of which Lambert had so expertly contrasted with Annie Sullivan, the main character of this, the undisputed best comic of 2012. Self-help books tell you that the behaviors that irk us the most are the ones we see reflected in our own lives, and while I'd buy that, I'd wager that what drives us even crazier is seeing a person--a real one, with emotions and struggles and all the rest--whose selflessness and capacity for concern so completely dwarves our own as to render our most basic daily actions the province of unearned luxury. Real heroism is rarely applauded while it occurs, the admiration comes afterwards. When life throws us amongst those who actually sacrifice themselves, body and mind, we're more likely to recoil in fear.

My first impulse after reading Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller was to find out who had helped Joe Lambert make the comic. Initially, I chalked that up to my hyperactive cynicism and every ugly part of my personality, each of which Lambert had so expertly contrasted with Annie Sullivan, the main character of this, the undisputed best comic of 2012. Self-help books tell you that the behaviors that irk us the most are the ones we see reflected in our own lives, and while I'd buy that, I'd wager that what drives us even crazier is seeing a person--a real one, with emotions and struggles and all the rest--whose selflessness and capacity for concern so completely dwarves our own as to render our most basic daily actions the province of unearned luxury. Real heroism is rarely applauded while it occurs, the admiration comes afterwards. When life throws us amongst those who actually sacrifice themselves, body and mind, we're more likely to recoil in fear.

Like I said: that was my initial feeling, and a few days, I abandoned it. It wasn't my own petty inadequacies that Lambert's comic forced me to acknowledge, it was the subtle way he presented the synergistic relationship between two minds for me to observe, two minds working so closely together that it humbles the word intimacy. Never before has a comic brought so close to bear those dusty what-are-we questions of philosophy, by showing us how one woman's absolute faith in her own abilities taught another human how to be. To be challenged by the relationship between Annie and Helen is to realize how tender and magic the design of one's mind truly is, and how blessed we are not to have to design its creation on our own.

It's more than just the miracle worker stuff, of course, and Lambert's use of a particular incident from Keller's post-therapeutic years brings a telling, troubling question to bear, one that he chooses (rightly) to leave as unanswered as it must have been for Annie herself. Where does Helen really begin? Someone whose adolescent period of unbiased, unblinking ingestion was extended past all but the most disturbed upbringing, a woman whose capacity for original thought remained without audience, and then with an audience of only one, in a language the two of them constructed? (This is a brusque description of the two women, easily punctured--it's the problem that consumes us, not the particulars.) By the close of the book though, the lack of stock answers seems both unsurprising and satisfying, a conclusion effortlessly achieved by the contagious nature of Annie Sullivan's unsentimental stoicism. This was everything that comics so often claims it can be--mature, intelligent, beautiful--and yet so rarely approaches. An unrivaled triumph.

It's more than just the miracle worker stuff, of course, and Lambert's use of a particular incident from Keller's post-therapeutic years brings a telling, troubling question to bear, one that he chooses (rightly) to leave as unanswered as it must have been for Annie herself. Where does Helen really begin? Someone whose adolescent period of unbiased, unblinking ingestion was extended past all but the most disturbed upbringing, a woman whose capacity for original thought remained without audience, and then with an audience of only one, in a language the two of them constructed? (This is a brusque description of the two women, easily punctured--it's the problem that consumes us, not the particulars.) By the close of the book though, the lack of stock answers seems both unsurprising and satisfying, a conclusion effortlessly achieved by the contagious nature of Annie Sullivan's unsentimental stoicism. This was everything that comics so often claims it can be--mature, intelligent, beautiful--and yet so rarely approaches. An unrivaled triumph.