ART? WHUZZAT?

GROTH: Has it ever occurred to you that you can’t really subvert the status quo so much as do a variation on the status quo, and that, in fact, you’ve now become the status quo?

MCFARLANE: Yeah, you’re right, I have become the status quo, but not through my making. I didn’t set out to go “I’m going to change comic books so that everybody looks like me, draws like me …” I just go, “I want freedom, you guys understand? I don’t want to draw like everybody else, just let me draw like I want to draw.”

Is that such a tough thing to comprehend? As a company? “Why don’t you let 10 people draw Spider-Man 10 different ways?” I don’t see why that’s a big problem. They seem to have a problem with that. So I’m going “Why won’t you have 10 different people draw it 10 different ways?” Because you know what it does? That will keep those creative people on those books a hell of a lot longer than saying “You got to draw like this, this, this.” People get tired of drawing like somebody else. They want to do their own thing. Especially people who got some kind of fire burning in their belly about comic books. They go “Ahh, I want to do this cool thing,” or whatever else. I did it, and you’re damn right I became the status quo. The very thing that I fought for was to not become the status quo, because I don’t want to draw the same thing, it’s been done, it’s been done, it’s been done … my style and some of the things I did became the status quo. Like I said, that’s a compliment and a frustration at the same time. Now, some kid, might even be my own son some day, has got to go in there and break down that same fucking wall that I crumbled once. I proved to them it can be done a second way, and now they’ve just gone and erected that same fucking wall back up. It just got a different name on it this time around. I’m going “Jeez Louise, why can’t we crumble the wall and let it lay and open up the doors and let this thing come out more than one different way?”

GROTH: Now, don’t you think the answer to that might be for future artists to do something wholly original?

MCFARLANE: [Long pause.] Whew. [Another long pause.] That would be an idyllic situation, but we got to deal with reality now, at this point.

GROTH: But Todd, there are artists who are doing things wholly original.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, oh, you’re right.

GROTH: They’re dealing with reality. So it’s not like reality prevents you from doing something original in an absolute sense.

MCFARLANE: Everybody does come up with something wholly original? No, you’re right, the guys who come up with the wholly original stuff get a lot of acclaim, and get a lot of people talking about their stuff, and they’re deserving of most everything that they do, and I’ll be the first guy to back them up. Even though they were told to do the same things, somewhere along the line, talent and ability comes in there. That’s something that I wish I could figure out, because then I’d spread the answer or words of wisdom but that’s something that is an unknown quantity. None of us can take into account, really. We don’t know who’s going to be the next original guy in comic books. If you know that answer, then please give it to me, because I’d like to know. I’d start looking at that guy’s career right now.

GROTH: Right. Well ...

MCFARLANE: And the other thing, Gary, that you also got to look at, too, is that a lot of guys that are doing mainstream superhero comic books, they’re breaking in at 19, 20, 21, 22 … this is like a dream of theirs, to work for this company. They’re looking for a steady paycheck, and even if they had something that was original, even if it’s there, it takes a lot of fight to get it out on paper, and a lot of people aren’t going to buck the system when they’re young. You don’t go on a new job and start telling the owners how to run their business. What ends up happening, I think, more than anything else, is a lot of originality is squashed by the time those people may be in a position to use it, they’ve forgotten what it was, or are out of practice, or they’re too comfortable doing what they’re doing that they never ever bring that to the surface again. They become the consummate professional, the contented guy. To me those are worse cusswords more than being an asshole, I guarantee it. I don’t want no fucking consummate professional, and I don’t want no contented guy. I want the guy who rams full speed into a brick wall, because I think those guys accomplish more things. If nothing else, they’re cooler to watch, anyway. “Look at that guy, he’s beating himself to a bloody pulp.” You know, I don’t agree with it, but … that’s why I like you, Gary. There are a lot of guys who think you’re a fuck, I hate to say it. You don’t have to print that in your own book …

GROTH: It’s hard to believe.

MCFARLANE: That is hard to believe, but I’m just saying that they don’t understand that the Gary Groths of the world have to exist for a reason — number one, so that he can show why everybody is so nice, and why he’s such an asshole. Good can’t exist without evil, so we’re all serving some kind of purpose, I guess … The other thing is, if you accepted everything, and you said to yourself, “OK, superheroes is where it’s at. I’m going to put out a book just like the Wizard” — and the Wizard’s doing a good job, because what they’re doing is on the right track for what they’re aiming for — but you don’t accept that, so you’re not accepting that, you’re doing what you want to do, you’re following it. Fine. You might not be “succeeding,” what we could consider success, but at least you’re following your heart. I think, in a weird kind of way, I’m doing the same thing. I want to do super-hero comic books. In some ways, I fight over things as much, maybe if not more, than you do, in mainstream comic books. It’s just that I’m fighting for things that are important to me, that to you might seem completely frivolous. Or vice versa. I always felt that…

GROTH: Well, don’t you think that …

MCFARLANE: … you and I should not be mortal enemies, Gary.

GROTH: Yeah?

MCFARLANE: Quite the opposite, we should be shaking each other’s hands, going, “I don’t quite agree with you, I’m a pacifist, but I’m damn glad that you like shooting guns and protecting my bolder from the enemy.” Fuck, you don’t want me to protect your border because I’m a pacifist, I’m just going to let everybody in. “Aw, thank you come on in. Aw thank you come on in.” I’m glad there’s guys out there that think the opposite of me. In a weenie kind of way, we should almost rejoice in our differences, but if that was true too, we’d have world peace, so … being individuals and having bellies and fires in our bellies…that’s the spice of life, bud.

GROTH: Right. Well …

MCFARLANE: Let me ask you this question: what are you trying to accomplish? I get somewhat confused with your book.

GROTH: The Comics Journal or…?

MCFARLANE: The audience that you’re selling to already doesn’t like mainstream stuff. For a while there you were mainstream-bashing and I thought it was almost redundant because the people buying your book already know that. They go, “Ahh, fuck, I haven’t bought a Spider-Man book for 10 years.” They’re already on to stuff that’s more hip, that’s more mod, that’s more original, that’s more innovative, that’s pushing the envelope, so to speak. Sometimes I almost think that you’re voicing something to an audience that’s already in agreement with you.

GROTH: Partly that’s true, but you have to remember that when we were criticizing mainstream comics quite a bit, that there were very few alternatives. The Journal started in ’76, and in ’76 undergrounds and alternatives were pretty moribund. There just weren’t any. Then, as alternatives started coming onto the scene, I think you probably noticed the Journal criticized mainstream comics less and focused more on the alternatives … which was a purposeful shift in focus.

MCFARLANE: I know I made this comment to you once, a couple of years ago when we were in Dallas, and we were on that same panel; that the only thing that I’ve never really been able to figure out about the Journal or yourself personally, is … it almost seems like you forgot what it was like to have been a kid. You forgot that you collected Hot Wheels, you forgot that you liked G.I. Joe, you forgot that you were into all those cool things ... and when you’re facing an audience of 12-year-old kids, they’re frustrating you because they’re doing kid things.

GROTH: You’ll remember though, that there were a lot of grown-ups in that audience.

MCFARLANE: I hate to say it, but 90 percent of them were there because they said that Todd McFarlane’s doing a panel. As a matter of fact, that was what made it fun, because I knew that you were going to shock the shit out of them. All these little 14-year-old kids came in there and I’m going, “They don’t know what they’re getting themselves into. Gary Groth is going to insult these guys before this is over.” And you did exactly what I thought you would do, you insulted them, you hammered them. But it makes more sense to take a 35-year old guy, because then you can actually come back and discuss the pros and cons of your discussion. But you don’t go into a room of 200 kids that got Spider-Man tucked under their arms and tell them that I’m a geek and they’re fanboys. I mean Gary, they were there! Fuck, they took you on. I’m going, “Way to go, kids!” I didn’t even have to say nothing. Way to go, kids. My only point was, that out of those 200 kids, eight of those guys are going to turn into Fantagraphics fans someday. But because you insulted them, one of them might not. That’s your audience.

GROTH: I’ll accept the odds, yeah.

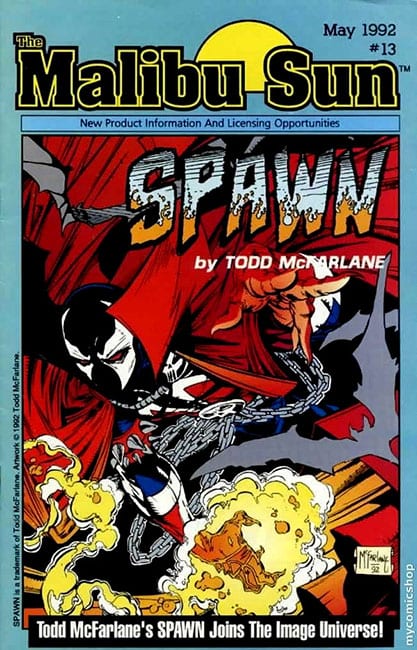

MCFABLANE: Whether you want to accept it or not, they, and the guys that are buying Spawn today are your future audience, and you’re going after guys who are actually going to be your allies some day.

GROTH: But Todd, in a way I suppose that’s my point. What I see happening is that when people grow up, they still don’t grow out of the kind of comics that they read as kids, they just want more of the kinds of comics they read as kids, and they don’t grow into anything more adult. [Long pause.] Do you see what I mean?

MCFARLANE: Yeah, I guess I … I mean, I don’t follow that, I don’t follow that much, I don’t know. My guess would be — and maybe I’m way off — that a guy gets 20 and he just goes “Ehh, I’ve read it, I’ve seen it, I’ve done it. I need superheroes, but I need them with a twist, so give me Dark Knight.”

GROTH: Part of the question is … what kind of work has the best potential to enhance the life of an adult? I think most of the pap being produced in comics is not that kind of work. And the more of that that’s produced, because of the intricacies of our economic system, the less mature work is able to be produced. I find that very disheartening. When the sales of Image Comics goes up, the sales of alternative comics goes down.

MCFARLANE: You got a good heart, then, and you want to better the world. In other respects, I think you’re not dealing with reality because reality … the public dictates to us, we don’t dictate to the public.

GROTH: The public is manipulated quite thoroughly by retailers and distributors and large corporations like Marvel comics. I’m not saying they have an absolute control over the public but they certainly do move public appetites in certain directions.

MCFARLANE: OK, yeah, I guess that’s true … let me ask you a question here. Love and Rockets, I don’t know the circulation of that …

GROTH: It’s about 24,000.

MCFARLANE: OK, 24,000, that’s a good solid number. If that all of a sudden started selling 2.4 million, don’t you think that all of a sudden … like, at what point does it go from having the freedom to be wholly original, to being something that’s commercial, and then hence, because it’s commercial, then you have to follow a certain format … you know what I’m saying?

GROTH: Sure, sure.

MCFARLANE: Could, technically, Love and Rockets sell 2,000,000 copies per month and still maintain what makes it so, so … fresh, I guess is the word …

GROTH: And still maintain its integrity?

MCFARLANE: Yeah.

GROTH: I think the answer to that question is, if Love and Rockets sold 2,000,000 copies a month, we’d be living in a radically different world than the one we’re living in, where “commercial” would equal “good.” [Long pause.] So, if you follow the logical train of your hypothesis, you’d be positing a radically different and probably better world than the one we live in now.

MCFARLANE: Uh … shoot, that’s pretty deep. You’re just telling me what you think a better world is. You put your own personal view on what you think is better stuff.

GROTH: Of course.

MCFARLANE: So now Gary Groth has become the dictator of what’s to be in comic books at that point. So then if we allow you personally to tell us what are good comic books, then in a weird kind of way you’ve now manipulated us, the general public, because you’re only giving us what you think is good. So aren’t we being manipulated then, at that point?

GROTH: Do you think all education is manipulation?

MCFARLANE: That all education … ?

GROTH: I would like to see a public that is educated at least to the level where they would appreciate better work than they do now.

MCFARLANE: I know, but then there’s no end to that puzzle.

GROTH: Which puzzle is this?

MCFARLANE: If we educate them to appreciate more than what they have now, then they’ll get to that point, and then we’ll educate them more to appreciate that where they’re at now isn’t as good because we can do better, and the next level, so …

GROTH: Well, that’s true.

MCFARLANE: So where does that end, then?

GROTH: It doesn’t end. There’s an old saying that “the good is the enemy of the better.’’ Theoretically, I suppose it shouldn’t end, people’s quest for excellence or quality or a qualitative life shouldn’t necessarily have an ending point.

MCFARLANE: I’m going to agree with you on that one, except for one thing: if everybody has the same opinion of what’s good … in my opinion we’re all dead men then. Because we have a Utopia. I fear Utopia, because I’m going, “Fuck, we’re going to all eat spaghetti and macaroni and like it?”

GROTH: No no, I agree that that would be sterile, but I think it’s probably possible to have a pluralistic society that simply has more elevated tastes than they do now.

MCFARLANE: Is there anything in our society that you think that we’re good at? In other words, in comic books we got bad taste in …

GROTH: We’re really superlative at picking politicians.

MCFARLANE: Pardon me?

GROTH: No, just kidding.

MCFARLANE: Aww, I know … Is there anything that we know is good that we accept it’s OK? Like, is it OK to wear blue jeans? [Laughter.] Blue jeans are commercial. They’re comfortable, they’re practical. Does that make them wrong? I think I’ve seen you in blue jeans and I’m going, “Gary, aren’t those fucking Levis you’re wearing?” So, all of a sudden … are you wearing Levis because they’re practical and they feel good, or because everybody wears blue jeans and you don’t want to wear those little Bermuda shorts that you used to wear as a kid and everybody made fun of you?

GROTH: [Pause.] Right. Um … [Pause.] Well … [Pause.]

You’re confusing things here. I don’t think you can really draw an analogy between bluejeans and art.

MCFARLANE: I’m not drawing a comparison between blue jeans and art … blue jeans are practically as commercial as they come, “status quo America.” Blue jeans and T-shirts are as commonplace as things come — and burgers, let’s say. So I’m assuming that you, the person of good taste, have had burgers. I’m just saying … is it OK for you to want to elevate the betterment of society to be better choosing their comic books and their literature, but it doesn’t matter how they dress or what they eat for fast food. I mean, I admire some of your goals, I’m just trying to figure out personally, from you … or do I just call you Jesus at that point? And I’ve said, “Ah, Jesus, that Gary …” but I don’t mean like that. There’s a comma, usually, in there. I think it’s good if everybody had one fight in them. I’m just trying to see how deep your fight is. If everybody fought over one thing ... I think that’s good, I think, because a lot of people don’t even have one thing to fight over. I just don’t know whether your fight ended with everybody reading good comic books, or once you accomplish that whether there’s something else that is your next battle, or whether you’re worried about the next battle once you accomplish this one.

GROTH: Well at this point I’m not sure I’ll ever accomplish this one, but … I might take this one to my grave, Todd.

MCFARLANE: I’m sorry, but … I think you are, bud.

GROTH: Did you say you sort of agree with what I said? Do you think it’s a good thing for people to strive for … higher aspirations?

MCFARLANE: I agreed with a lot of things in there. I don’t agree with all of them. I agree in the fact that, you’re right, we should strive for better things in life, but we get into an almost impossible puzzle. We should strive for something that’s better, but I think we should strive for something that’s better for us, personally. What’s better for me, personally, might be repulsive to you, personally. Or vice versa. If I like to read Harlequin romances, and I get something out of Harlequin romances, then to me it’s OK that they’re there. Let the cream rise to the top. Part of it is manipulation, like you’re saying. But, unfortunately, all I can do as a lonely employee is either accept it, fight while I’m with the company, or eventually quit, and I’ve done all of those things. I think that I’ve somewhat lived up to my end of the bargain. I bitched about it, then I finally quit, because it’s got to the point where it’s, “Todd, you either accept that the system’s this way, or try and do something about it. Will you ever succeed? Probably not. Gary Groth’s probably never going to succeed.”

But at least we tried something. Is it better than anybody else? Ah, that’s being kind of ego-weenie if we say yes, but it does something for us, personally, to fight this battle. God forbid everybody would start to agree with me, because then I wouldn’t have no battle to fight and I’d be bored. I hate to be bored I’m actually glad that there’s guys up there that totally think I’m a moron. “Aw cool, I’ve got an opinion there!” If you want to keep delving deeper, then we start getting into religion and that’s a whole ‘nother ballgame that makes totally no sense to me either.

There’s a reason why we’re individuals. There’s a reason why some of us are fucks, and I’m a fuck. I just wasn’t created like this. Somebody knew I was going to be a fuck. If you’re religious, and you believe in higher powers, then there are actually people that have gods out there that knew upon conception that Todd was going to be a fuck. In my weird way of thinking I can never go to hell because whoever allowed me to exist knew I was going to be a fuck, so I’m just following my path. Doesn’t make any fucking sense to me. I mean, French-fry me, send me to the party downstairs, because I never heard of the devil kicking somebody out. He seems to be a lot happier of a guy, a lot more accepting. “Aw, you’re an asshole, come on in. Ah you’re a good guy — so he made a mistake — come on in. Aw, you’re a bad guy, come on in.” Why do we need something that’s big dictating over us?

That’s why sometimes I get kind of weird about anything that’s even smaller than that trying to dictate to us. I guess maybe I’m … maybe New Age or something … I’m totally atheistic. The best we can hope for, I think, in life, is to be a good example. That’s it! And let other people either follow that example or not. You can voice your opinion, you can say this, I can go the exact opposite, you can be black, I can be white, and all we can do is be good examples of those blacks and whites, and hope that people follow in our paths. All I can do is love my wife, and I hope my children grow up and have a happy marriage. But if they don’t, I don’t really see that that’s a flaw of mine, because I loved my wife in front of them and we came across as good examples. I did my best. That’s all I’m trying to do in comic books. It makes me happy. I’m leading by example. I’m not doing the perfect superhero comic book because to do superhero comic books it has to be somewhat commercial, because it’s a big audience out there, but…you can’t really call me content all that much. I’m always doing something that’s fucking with somebody. Like I said, you don’t get to be called an asshole for nothing.

REEDIN’, RITEIN’ AN’ REESPEKT

GROTH: Do you think your comics are well written?

MCFARLANE: Do I think my comics are well written?

GROTH: I asked you first. [Long pause.]

MCFARLANE: No.

GROTH: Well, that’s probably not a good example for you to set, is it?

MCFARLANE: Whew … I can swing either way on that one. It depends on what mood I’m in that day. See, I think what makes my comics work is that the whole is better than the parts of it. I don’t think I’m the best storyteller out there. I don’t think I’m the best artist, the best inker … but somehow when you put those in the pot and you stir that thing around, it does something for a lot of kids out there. Is it perfect? Nah, Gary, but it’d never be perfect. Could it be better? Yeah it could be better, but I don’t know that the trade-off of working with a writer that’s better than I am — which is probably 95 percent of them out there that the trade-off would be that I’d be frustrated, so that all of a sudden, my mind would start to go, and the whole cycle starts all over again. All I know is, personally, I’m doing what I know is keeping me personally happy. Is it the best written stuff out there? Nope. Is it the worst? I don’t think so. I’ve only been at it for a year, so hopefully I’ll get better. I’m not saying I’ll achieve in writing what I achieved artistically, that the kids’ll think “Wow, this guy’s the next coming of Alan Moore,” or something like that. It would be nice, and I would dearly love that, but I don’t know whether that’s within my abilities right now.

The flip side is, are you cheating the public because you could actually be giving them a better product? That’s a viable fight that you could say that to me, but all I’m saying in return is that I don’t know how long that I would remain on that book, because I’d be doing somebody else’s ideas, I wouldn’t quite agree with it, and the whole cycle would start all over with me again. Unfortunately, all I know is I’d be right back where I was. If I got you to write it, in three years I’d be right back where we are now. Aw, I’m too much of a wiggy, weenie asshole … or worse than that, I’d actually learned something from them and I’d go, “Huh. OK, I learned everything I need to from Frank Miller, I think I can do it without Frank Miller. Thanks for the help.” I’m like that.

GROTH: But if you’re doing something better, don’t you think you should be able to change your own private predilections to accommodate a superior achievement?

MCFARLANE: No, uh . . .

GROTH: I mean, you must have some control over what makes you happy, and just because you become antsy by, say, collaborating with someone else and doing something better than what you could do on your own … doesn’t necessarily mean you should willfully refuse to do so.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, I guess that’s where you and I differ: doing something better, and it happens to be comic books, is not all that big of a thing to me personally. Could I turn out a better comic book? Yeah. Would it make a difference? If I got a better writer, would that make you any happier that there’s a Spawn comic book, a superhero with a cape who comes back from the dead and has superpowers — but it’s written very well? Would that make you any happier? I doubt it, and it probably wouldn’t affect the sales one iota, so given that it’s not going to make you any happier, and it’s not going to make the kids any happier, and it sure as hell ain’t going to make me any happier … why go to that level, then?

It’s not going to do anything, really. It’s just going to be better for better’s sake, but it doesn’t keep you happy, it doesn’t solve your problem, it doesn’t solve the kids’ problem, it doesn’t solve my problem … We’re just doing something for the sake of doing it, so why do it?

GROTH: Right. Well, you know, artists achieve excellence any number of ways, obviously, but certainly the common denominator is that they cultivate their resources as human beings, and that’s reflected in their art. Perhaps the first thing you could do is aim higher than superheroes. One thing you said was …

MCFARLANE: U- oh. These guys, Gary, could be misquotes, too. You tell me, and I’ll tell you … these could have been taken out of context.

GROTH: OK. You tell me if you’ve been misquoted. You’ve said, “To tell you the truth, I don’t read, which is why it’s a joke that I’m writing.” You’ve also said, “To tell you the truth, I’m probably an ignorant person.’’ It seemed as if you said that with a certain … satisfaction.

MCFARLANE: Uh-huh.

GROTH: Now it seems to me that one of the first things you could do to expand your resources as an artist is to become less ignorant.

MCFARLANE: [Long pause.] Uh …

GROTH: You might be a better artist if you were less ignorant. But, you seem reasonably content.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, I’m, uh … I just don’t … I …you got me pinned in the corner here, because I don’t read, and you’re right, it is kind of funny that I’m a writer. You know what I mean?

GROTH: Yeah.

MCFARLANE: More than that, though, it’s kind of frustrating to writers out there.

GROTH: Or irksome.

MCFARLANE: Because, then, either it doesn’t really fucking matter what people write, then, because if I can do it, and I can sell 1,000,000 copies with bad writing, then what the fuck is the problem? That brings us to the argument, then, that maybe the artwork is more important — that’s a whole ‘nother discussion then, at that point.

GROTH: Or maybe most comic-book readers don’t care about the writing.

MCFARLANE: Then I’m going, “OK, they don’t care about the writing? Perfect then! It’s a good thing that I’m a better artist than writer right now, then.” I mean, the fates are looking down on me. Even when I don’t try, I seem to somehow succeed. I’m ignorant on a lot of things, but I think that I’m somewhat well-balanced in life, such that I’ve been thrown into a kind of a fame and fortune …

I’m a fuck, let me tell you about it, but you know what? The kids never see that side of me. When I’m in front of the kids, because they’re the most important thing to me, I’m a pussycat. I owe my life to every single one of those kids that buys my book. I don’t care if they’re 8 or 28, or 88. It’s the readers that I owe everything to. I don’t give a shit about the fucking other people that are along the chain. They exist because, ultimately, because of those kids. The distributors can think that they’re doing something that’s grand and whatever else, and they are, but they wouldn’t even exist if people didn’t want comic books. The retailers are doing a great job and I love them but they wouldn’t be selling comic books if the kid didn’t want to buy comic books. Now, somewhere down the line those kids are buying the comic books, so when they react to my stuff, and I read my mail …

If I make any changes, it’s from the fan mail: “I think, Todd, that this character’s a little bit too dark and morose for us, I think he’s too happy, I think he’s too fat, I think he’s too wide” — I react to those kids, because they’re my buying public. Editorial people, or anybody else along the way says, “Todd, don’t make them fat” — why? “Just because.” That’s not a good enough answer to me right now in my life. The kids, unfortunately, when they’re sitting there going, “He’s too fat, because he looks like a little lump of … ” — they’ve actually got a reason why they think he’s too fat. Nobody else along the chain has it, so …

I’ve been thrust in a position where I can either be a fuck or an ignoramus. I can play any game that anybody wants me to play. I think that I can play them, somewhat, with whatever skill that I have. I should have been an actor. I think I perform very well. But I also know that I’m not good at everything that I do. I’m better at other things. But I don’t think that, just because I’m not good at somethings, that I’m not good at being a writer — that I should have a better writer on my book.

GROTH: But if you respect writing, and you respect your audience, wouldn’t you try to make yourself a better writer?

MCFARLANE: Uh-huh.

GROTH: But you don’t read anything!

MCFARLANE: No, I don’t read anything.

GROTH: So how can you make yourself a better writer if you don’t study writing and read other authors?

MCFARLANE: Maybe there’s my ignorance there, because I don’t think that if I read Shakespeare I’m going to become a good comic-book writer.

GROTH: Well, I don’t either [resigned].

MCFARLANE: I don’t know what you want me to read. I mean, if it’s technical stuff, you’re going to have a tough time, because unless it’s got pictures … I can’t read black and white, other than the box scores. I just don’t have that mentality. I’ve got to have pictures in front of me. I don’t read comics! I don’t read nothing really. I read the sports page … and then The Comics Journal — I’m going to give you a plug. Actually, that’s black and white. I do read that and whatever else. It’s not like I don’t have somewhat of a mild vocabulary out there.

I could turn out a better product, Gary. Yes, you’re darn tooting. I could turn out a better product but I don’t see where it would accomplish anything. I guess the difference is, I don’t think I’m cheating the kids by not having a better writer on the book because I read the mail, and most of the people that are my audience, Todd McFarlane’s audience, don’t seem to be in as much of an uproar as maybe my peers are. They go “Ah Todd, it’s cool pictures, love that cape all over the place, it’s not the best written book…but it’s not the worst, and since we got enough money to buy 20 comic books a month, we’d put it in there between one and 20, it’s good enough for us to take home.” That’s good enough for me right now. I don’t need to be the best artist and the best writer … those are not goals that I ever set out for myself. I just wanted to do comic books, and have a fun time doing it. If I set out any goals, I’m doing it right now. I’ve got total freedom to do whatever. It’s not the best, but I got total freedom and I’m having a hoot doing it. Fortunately, enough people are buying it that allow me to keep doing it. Whether that’s right or wrong … I’m not the one you have to argue with. You better start going after the kids and say, “You better stop buying that Spawn stuff, because it’s a piece of crud.” I don’t have control over my audience. If it’s crap … turn off the TV if it’s an ugly show. Lay down the book if it’s a bad book and don’t look at the art if it’s bad art. I don’t have control over the public. All I do is do my comic book, and they seem to buy it, and I’m thankful that they do because otherwise I’d have to come up with another occupation.

GROTH: Sounds like you can relate to Dan Pussey.

MCFARLANE: To who?

GROTH: Dan Pussey, “Young Dan Pussey”?

MCFARLANE: Dan Pussey?

GROTH: You haven’t read the strip in Dan Clowes’ Eightball? He does a strip about a superhero artist.

MCFARLANE: Uh, no.

GROTH: I can’t believe you haven’t read this! Todd, where have you been?

MCFARLANE: You know, to tell you the truth, I don’t know what’s going on with the other Image comic books, so I don’t see how that’s surprising.

GROTH: You don’t even read other comic books?

MCFARLANE: No, I told you; the sports page. Unless it’s in the sports page…

GROTH: The sports page. That’s it.

MCFARLANE: I expect people like you to keep me abreast of all the things that are happening.

GROTH: That’s what I’m here for.

MCFARLANE: And all the things you’re telling me, like who’s writing letters to the CBG and stuff like that…I’ve done interviews in the past, I can only answer your questions that you pose to me, I don’t suggest the questions to you. Maybe my answers do, but the one thing is, I’ve never written a letter to anybody. I’ve never sent a letter to you, I never sent a letter to Amazing Heroes, I never sent a letter to the CBG. I don’t feel that I should have to answer my critics.

GROTH: Right. So you don’t read many comics, either.

MCFARLANE: No.

GROTH: And you don’t read Cerebus or…

MCFARLANE: I don’t read none of them.

GROTH: None of them. Zippo.

MCFARLANE: OK, I’ll read the odd Cerebus because Dave Sim’s a funny guy. I just like the way his characters look. But I get bogged down. I don’t got a long concentration span, you know what I mean? I don’t read Sports Illustrated because the articles are too long. I just like short, concise, little … give me the quick five facts and get me in and out. I just want facts so I can be good at Trivial Pursuit and that’s all. But let me tell you, when I’m drawing, bud, I come up with plenty of opinions. I’ll argue politics and religion and art with you until doomsday and I actually can sometimes, actually confuse people, so it’s …

GROTH: I have no doubt of that.

MCFARLANE: Though I don’t read about it doesn’t mean that I don’t think about it, and that I don’t formulate opinions ...

GROTH: Right…Do you think your work is better than mediocre?

MCFARLANE: What work? I mean, the whole of it, or the art, or writing … ?

GROTH: All of it together. The writing and the art taken as a whole.

MCFARLANE: [Long pause.] Yeah, I think it is. I get enough comic books that I look at and I go, “I think that artistically I put in a lot more time than other guys. I think pages through maybe a little bit more than guys, I try to come up with something that might be a little flashy…” You know what I mean?

GROTH: Uh-huh.

MCFARLANE: I could just rely on the same 10 gimmicks over and over. Some issues I’m lazier than others, but … Would I ever say that I’m one of the top guys? Never. I could give you 100 guys that I think are better pencilers, inkers, and storytellers than me. I don’t get why I’m at where I’m at. It’s as much of a mystery to me as it is to anybody else. But some things are not a mystery.

When I looked at comic books, and I started collecting when was 17, I started going backwards, all the way to the ’60s. I liked ray guns, and I liked action, and detail, and cool looking stuff, and at that time that was John Byrne and George Perez. To me, I see that that’s what Jack Kirby was all about. He did all that stuff, and I just feel that I’m carrying on, basically, a tradition. It just happens to be repackaged in a ’90s style, but it’s still essentially Jack Kirby comic books: it’s big characters with big muscles doing majestic stuff in majestic poses. There’s no magic to what I do. I just maybe do it with a little bit more of a flair or a gimmick than a couple of other people. The kids react to it. I don't got no control over that.

“KING” KIRBY GOES TO DISNEYLAND

GROTH: Let me skip back a few minutes. My understanding is that you, basically, left Marvel because you didn’t like the way you were being treated, that you didn’t like the way Marvel, and probably DC, treated creators over the last 50 years. I think you said that.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, I totally disagree with it. I did since day one.

GROTH: Let me ask you about something else before I forget. You had a meeting, I think, with Tom DeFalco.

MCFARLANE: And Terry Stewart, the president of Marvel Comics.

GROTH: Can you tell me the circumstances, and what happened?

MCFARLANE: I set up a meeting with them. I was going to see them anyways, and at that point [Image] had solidified: Rob was there in New York and we had basically signed up Jim Lee the week before … I said, “I’m going to see them, if you guys want to come in there with me. Because I’m going to tell them something, and it looks a lot more impressive if there’s three of us there, especially three of their big boys. You guys don’t have to say nothing, just come in there and lend support, more than anything else.” Essentially, I just felt that for us to just quit and not tell them wouldn’t have been fair. I was going in there to say, “Hey; we’re quitting. We just want you to know. Here’s some of our reasons why we’re quitting, but we don’t want nothing in return for it. We’re not quitting but saying ‘If you do this, we’ll stay.’ We’re just saying we’re quitting. Here’s our reasons. Do with that information what you wish.”

GROTH: What reasons did you give them for quitting?

MCFARLANE: Essentially, that they lost sight of the fact, because of their corporate structure, that flesh and bone do their comic books. I can’t say it any more simpler than that. That they have lost sight of us, the actual creators. That, yes, Spider-Man is big, he’s an icon, and he’s going to make you 1,000,000 bucks, but you want to know what? If Ditko and Romita and Ross Andru hadn’t existed, maybe even myself to a little bit, maybe Spider-Man wouldn’t be quite as popular today. Maybe he’d be twice as popular because somebody else would have replaced us — we don’t know that, because that’s hindsight. All we can go on is actual reality. Reality says that there’s people along the line that have done things that have kept those characters alive, that have got people interested at different cycles of the character’s life so that your company can continue to flourish. You basically have forgotten those flesh and bloods.

In such a way, I, Todd McFarlane, am benefiting from Jack Kirby’s sweat and blood, and Steve Ditto’s sweat and blood, and whoever else worked at Marvel. It was just time for us to quit, and go and do something. I don’t know if they’re ever even going to react to it. I don’t care if they change any of the rules. I would like to, because then I at least come up with something. But if I had my way and they changed a bunch of rules and made it so much nicer for us as creators to go work with them, then I still wouldn’t go back there. I’m not blackmailing them so I can go back. I’m just doing it because Kirby did it for me. It’s time for somebody else to lay some more tracks down, and not that they personally benefit, but that it might be better for the next generation. I’m a father, and sometimes you’ve just got to do something because you want your kids to have a little bit better of a life. Maybe that’s being egotistical, to think that I’ve got that much of a power base or that anybody should give a shit about what I want to do. But that, essentially, was why I was in there. I disagree with the system. I can only do one of two things: I can either continue to lend my name to the system and bitch or — option C — I can leave. And I said, “At this point, I’ve got to leave.” Is it a suicide trip? Quite the opposite. People go, “Todd, I really respect your balls.” There’s no risk factor involved, at least from my point of view and my career.

I look at it this way. I quit a couple months ago, I was doing a monthly Marvel comic book. If Image falls flat on its face, I’m good at groveling, I can go back there and I’ll be doing a monthly Marvel comic book or a DC monthly comic book. I haven’t lost one thing. Will it be as popular? Nah. Will I make as much money? Nah. Will I be as famous? Nah. But I’ll still be doing what I was doing; a monthly comic book. I’ll always be able to do a monthly comic book for those two companies. That’s the least of my concerns. From my perspective, I’m going, “Psst! Guys!” That’s what was frustrating me with trying to coax some of the people into the group, and some of the guys even now that we’re going after, is — there’s no risk involved! If this works and we can actually do whatever we want in our comic books, and live happily even though Gary Groth might not like the actual content of it, it’s OK. And I’m going “Cool.” I mean, I’ll be happier and ultimately, that’s where it came down to for me. If I’m happier, I’m a better person. And if I’m a better person, I’m a better husband, friend, and father. To me, that’s what life’s all about. I’m saying, “Guys, there’s other options out there. Why don’t you come for a ride and if you don’t like it you can always go back.” It’s like getting a haircut. Fuck, it’ll grow back, don’t worry about it.

GROTH: You also went over to DC, didn’t you?

MCFARLANE: Uh0huh.

GROTH: And you talked to Jenette Kahn.

MCFARLANE: Uh, not about me. I talked to Jenette before that, and that meeting was with Denny O’Neil and Dick Giordano and Terry Cunningham.

GROTH: So why did you talk to DC?

MCFARLANE: Just to give them the same warning shots. They thought we were talking about Batman projects, but we’d determined we weren’t going to do that. Just to say, “Guys … it’s not what’s good for the goose is good for the gander. You guys are no different than they are and we’re just telling you right now that you guys aren’t even an option to us. That their system and your system, as far as we see, are exactly the same system.” The only thing that they could come up with is that they’ve got new contracts that are coming up that are more fair to the creators. I only see that for one reason; their sales are not very good right now. They’re doing that for survival, not because they like us. And they’re coming out with a contract that’s better for the creator, except they fucking didn’t ask any creators what should be in that creator contract. That’s what that was all about. Our quitting was for one reason; they fucking don’t respect us. That’s it. We’re interchangeable … they’re writing a contract that’s better for our life without ever notifying us. Thank you for telling us what’s good for our life.

GROTH: What was their reaction to what you told them?

MCFARLANE: We caught them off guard. Marvel and DC are a little bit different. Marvel tries to not acknowledge its superstars’ status … they’d hanker on me for doing something because some guy who was selling a fraction of my books and I felt wasn’t doing as good an effort — they wanted me to emulate that. And I’m going, “No, why don’t you get that guy to try to throw the ball farther, why are you asking me to throw it shorter?” DC I found, does have a superstar “division,” I guess, if you want to call it that. I don’t think that’s fair either, because I used to be the punk, and I never liked it when they bumped me off books because so-and-so came over to the book. I vowed I would never forget being the kid that was on the other side of the table, asking for an autograph. So I remember the crap and I’ve got a long memory and those are things that rotted my gut, meeting assholes at conventions and having people take advantage of you because you weren’t a superstar early in your career, so I would never ask somebody to step aside for me.

That’s why I quit Spider-Man twice. Even though I knew that if I got in a battle between me and the writer I think I would have won, I never would have put that writer in that position. I had too much respect for him as another professional.

He’s a professional, I’m a professional, so before I put that other professional into a voting match or a decision match, I’ll quit. I’ll walk away. You know I would’ve won it. Now fuck, I’m out of here, I’m not going to put any editor or any other creative guy and sit there, because I’m Todd McFarlane, I sell lots of comic books and watch out for me. That was it. It was just giving them information both times. Do with it as you want, blow us off if you want, change a rule if you want, do nothing if you want — but we’re gone anyways.

GROTH: Did they have any reaction?

MCFARLANE: Let me just tell you something here. Producing comic books is not magical stuff. But they’ve brainwashed us for so long that people actually think they can’t survive without those two companies. They each had their own reaction to it. Marvel’s reaction pretty much was, “The characters will always be more important than the creators.” They stated that in some of the articles. And I know what they’re trying to say by that. I agree with that on a certain level. Say they buy 1,000,000 copies of Spawn, not because they give a shit about Spawn, but because they like Todd McFarlane. But by issue number 12,1 don’t think the Todd McFarlane name is going to be enough to satisfy the group out there. If I want to maintain some decent sales, what I’ve got to do is give them enough of a story and enough of a cool character that they’re going, “Give me that Spawn book by that, uh, whatever his name guy is.” They’re buying Spawn. On that level I agree that the characters are important, except it’s flesh and blood that gives fucking vision to those characters from day one, and they’ve not acknowledged that. They’ve not acknowledged what Jack Kirby did for those characters, they’ve not acknowledged what Ditko did, they’ve not acknowledged what Don Heck did. Don Heck wasn’t a superstar, but he kept The Avengers going for a long time so that maybe 10 years later John Byrne could become a superstar.

GROTH: What do you think Marvel should have done for someone like Don Heck? How should they have behaved differently than they did?

MCFARLANE: I don’t think that there’s any answer. I don’t know that there even is an answer to your problem. You can’t let the fucking prisoners run the prison. Then you got total anarchy. You’re a business group. I don’t know that if I owned this company I would run it any different than you guys. The only thing is, I don’t own your company, so I can’t live within that structure. Tom DeFalco is the perfect editor up there. If I were an editor-in-chief and I was a corporate head, I’d hire Tom DeFalco, he’s doing his job to perfection. I don’t begrudge him for it. The only thing I begrudge a guy like Tom for, is he has accepted the system, such that … you’re raised in a bigoted family, OK?

GROTH: Uh-huh.

MCFARLANE: Your dad says, “Ah, those goddamned niggers.” You have one of two things you can do, I think, as a kid growing up. I don’t really see that there’s any grey matter there. You can either say, “Dad, you’re right. Bunch of niggers.” Or you can say “My dad is ignorant. That’s totally wrong. I will never call a black person that name ever again. I think it’s totally wrong.” Now, given that scenario, I say I think it’s totally wrong to call somebody a name like that. Tom’s attitude, and corporate America’s attitude is, “This is the way it’s been for 30 years. It was good enough for me, why isn’t it good enough to you?” Well, I’m saying, “You’ve been calling people names for 30 years; it doesn’t make it fucking right, do you understand me?” I mean, I’ve used a few choice words. Just because we’ve been lopping the arms off babies, and they’ve learned to become all righ- handed and learned to live with one arm, doesn’t make it right that medically we can lop the arm off children now? And they can survive with one arm I don’t care they been doing it for 50 years. I told them, “As of today, I see that it’s got to be different. From 1933 to today, I don’t give a fuck how you’ve done business. It’s irrelevant.” I don’t care! Because I’m telling you, up to today, in my opinion, it has been wrong. Since day one. It’s been wrong for 50 years and to accept the line that “it just is” for me personally, that’s not good enough of a fucking answer for me right now, in my career.

GROTH: How could Marvel have shown respect to Don Heck or Jack Kirby to your satisfaction?

MCFARLANE: How could they do that? It’s not a money thing; I think some people have lost it — it’s not a money thing. It’s just the respect thing, you know?

GROTH: Uh-huh.

MCFARLANE: I think there’s easier ways of doing it. Jack Kirby created all those characters and I think he got hosed on them, fine, whatever, that’s another story. But you know, I think Jack Kirby would have been a lot more satisfied if once a year you made a T-shirt of his first Silver Surfer two-page spread — you made five of them and you gave them to him and his family and nobody else had those T-shirts. You know what I mean?

GROTH: Uh-huh.

MCFARLANE: Gave him a Thor watch or something like that. Or you took his sons and daughters or family out to Disneyland. Just minor stuff that would be a minimal investment, but because this guy is your investment, your flesh and blood, ‘cause he created so much, that it would have come back to you. He would have been happy, a good company man, you know what I’m saying?

GROTH: Well … yes…

MCFARLANE: Not cash. If you were to throw cash at him and shit on him, he still would have walked away. At a certain point the price is not enough for the bullshit people have to put up with in any job. But there’s ways of building loyalty amongst the people working for you where it doesn’t have to cost you. It’s more of an investment. Look at us as commodities that you’re investing in and we’re gonna pay off for you if you keep us happy.

GROTH: But that has nothing to do with respect, Todd. They’re just buying your allegiance.

MCFARLANE: I don’t know — you’re doing it because you respect the people you work with. I try to keep the people who work for me happy; I don’t do it to buy their allegiance, I’m doing it because I like them or think they’re doing a helluva job. I think I should be taking care of them or at least acknowledging them because they’re doing a service to me. Steve Oliff colors the book, I owe him something. Tom Orzechowski does a cool lettering effect; I owe him.

GROTH: Have you given Tom a Spawn watch?

MCFARLANE: No way, but I’ve got my T-shirts coming out. You’ll see ’em in San Diego. Called the “Moo Crew.” [Laughter.] McFarlane, Oliff and Orzechowski. There’s a “moo”… it’s got the Spawn eyes and the two O’s, there’s a big udder coming out and somebody squeezing the nipple and shooting milk, and it says, “We’re milking it for everything it’s worth.” Ah, yeah, I loved that … you’re gonna see the “Moo Crew.” I’m making two dozen that only myself, Oliff, and Orzechowski can have. So they can burn the T-shirts. I didn’t ask them for this; I didn’t approve the “Moo Crew” rumor. I’m going to give it to them; they can burn the thing if they want or give it to their neighbors. I’m just saying that at least I’m acknowledging that I want to do something here for no other reason than fucking around. The “Moo Crew.” The kids are going to stand in line and walk by and …

GROTH: OK, let me ask you something. You’re basically asking that Marvel respect its artists ...

MCFARLANE: Yup, yup.

GROTH: Now, do you want them to respect you as artists or as people who can make them money? Or do you make a distinction?

MCFARLANE: Ultimately, those guys are in it for making money, so at this point I’ll take it either way. The ideal situation would be a little of both; given that I won’t be picky at this point, I’ll take what I can get. If they say, “Guys, we’re in it for business and you’re keeping us in business,” that’s a good enough reason, right there. If they’re saying, “Well we like you…” It gets into weird things there once you start doing business and art. The guy who’s selling 20,000,000 copies, if they don’t like his artwork and don’t respect him, they think he’s an asshole. But he’s putting more money into their pockets so they can subsidize the other stuff that they want. They have to acknowledge him as much as the other guys who you think are 10 times the human being because you’re dealing with a lot of ego. Know what I mean?

GROTH: Yeah, yeah. If Terry Stewart calls you up tomorrow and says, “Hey Todd, I really respect you ability to make us money,’’ would you buy that? Or would you say, ‘ ‘OK, I acknowledge your respect and I’ll come back?’’

MCFARLANE: Uh, no. They acknowledged it a little top late. If I were starving, I’d come back, and I mean I wouldn’t have to grovel. Nah, in all honesty, I can’t see myself ever going back. I guess I’m the only guy who might say that out of the group; I’ve got too many things on my mind and 1,000 opportunities and I’ve only scratched a couple of them. By the time I ran through them all, I’d be 55 years old. I’d like to do crossover stuff with the company; I think that would be neat because it’d be something the readers would like. But to go back and work for them, I doubt it. You see, I didn’t quit and I’m not doing this for me to get anything out of this. Kirby quit and got Pacific to give him stuff and First Comics so that DC and Marvel stood in line after that, but Kirby didn’t really reap the benefits. That’s why I’m saying I’m hoping DC and Marvel change, because they should. But it doesn’t mean I’ll ever go back into the system; it doesn’t mean I want the system to change so that Todd McFarlane gets the advantage of it. If you want the system to change for the next generation. Whether that’s being a martyr or being a good guy or whatever, I don’t care.

I’m not doing this for me; I feel there’s other guys who cracked some of the pavement for me, it’s time for me to help crack it. Why not, you know? And I hope the guy five years from now does the same thing for the next guy. I don’t care that I get anything, as long as there are some changes in the business.

“PUT THAT ONE IN ITALICS!”

GROTH: Do you realize the system won’t change?

MCFARLANE: The system won’t change? Uh, I’ll go to my grave trying, but … I mean the system’s gonna change; something’s gonna happen. See, if one rule changes, I’ve won my battle. I can say to myself, “OK, fine, Todd, the little punk made them change one rule.”

GROTH: What if Marvel and DC sent out a form letter to all their creators saying, “We respect you. We love you.’’ Would that be enough?

MCFARLANE: Aw, c’mon Gary, you know better … actions speak louder than words, you know what I mean?

GROTH: So you’re primarily after material gain?

MCFARLANE: No, I’m after action. I just would like them to tap into us every now and then. We’re putting out comic books. God forbid they’d actually talk to the guys producing the comic books. That’s probably my biggest gripe. It just seems like it would be kinda nice for them to tap into Ditko, you know?

GROTH: When you say “tap into,” how do you mean?

MCFARLANE: Like, we – well, I’ve got no definition of it. Here’s what I would see if I was running that corporation, OK? Maybe this is not feasible: “Who’s a hot guy this week?” Give me the date … oh, it’s 1963. Steve Ditko. “Bring him into the office. Steve, here’s all the editors here, you’ve got exactly 45 minutes of our time, go. No agenda, no nothing. Talk about the Mets; so you waste 45 minutes of our time — who gives a shit? But if you got something to say, say it. If you’ve got something burning on your chest, or let us ask you a question, ‘Why do you think your comic book sells? We’re in the business of selling comic books; why do you think your comic book sells? Explain to us.’”

Every artist has a reason why they do everything. I’m not saying we’ve got the right answers, I’m just saying we have an opinion. And it seems rather weird that they don’t ever ask our opinion considering that their whole livelihood is pretty much based upon the flesh and blood that’s turning it out. They never really care why we do our stuff; all they seem concerned about is that we do it, period.

GROTH: You seem to see artists as being appendages to marketing and it’s my experience that most artists are either not interested or expert enough to give lectures on marketing. If I called up Robert Crumb and asked him to give our office a talk about why his comics sell, he’d think I was out of my mind.

MCFARLANE: OK, I guess I was a little too specific. What I’m saying ideally would be, “Robert Crumb, you’ve got 45 minutes, go.” That’s all. Understand?

GROTH: Yeah.

MCFARLANE: If Robert Crumb wants to talk about why comic books should be twice the size they are or why you should have printing plates or why you should stay poor, social stories, anything. You know what I mean? Gotta have an opinion about something and if so, even if you just got one thing out of that Robert Crumb talk, to me, that’s enough. And then the next month, or the next week or the next year, pull in whoever, Jack Kirby. “Jack, you’ve been doing a lot of things for us. We don’t quite like all of them, just go, talk to us, tell us something. What do you think about comic books?” I mean, whatever. I don’t care. I’m just saying I’ll take whatever I can get at this point. Just open up the forum right now. Let there be a two-way street that we can talk to the business we’re working for. But when do we get a chance to do that?

GROTH: Well, it seems to me patently obvious that most publishers don’t give a shit about you; all they care about is whether you sell books, and eventually, if the system changes to the extent where they invite you into the office and stroke you and give you perks and so forth, it won’t be a matter of respect; it’ll just be a matter of their buying your allegiance or buying your loyalty by giving you the illusion of respect. Would that be an acceptable change to you?

MCFARLANE: If I’m going to describe Utopia, no, it’s not. It would be somewhat better than what’s out there right now. Because at least for five minutes, they’re acknowledging it. Now, the real fucks out there, like myself, would see through it after a while. Some of us are just born to be fucks, you know? It doesn’t matter if you laid everything at our feet, we don’t really know what that final goal is, we just know we can’t take what’s there right now, you know what I mean? We’ll never get our hands on or something like that. I’m not saying it’s going to appease everybody, but I think that there’s some kind of middle ground there. It’s not going to work unless there’s some truth to it.

GROTH: Yeah. I can just imagine these guys in the boardrooms saying “Todd wants to spend a half hour with the office help. Give the jerk a half hour and get more work out of him.’’ I wonder if that really is any better. At least now they’re at least being honest about their indifference toward you.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, but if they come in there and they say, “We really want to hear your opinions, but we’re not going to do nothing about it,” that says something right there.

GROTH: They wouldn’t tell you that, though. They would say, “We would love to hear from you … ”

MCFARLANE: Hey, after three years of pulling people in and they haven’t changed one thing, then what’s the fucking sense of these meetings, since you don’t really give a shit? Ultimately, there’s ways to filter through a lot of the stuff. I’m not saying immediately, but eventually you’d be able to see through some of it. I don’t really know that they can do it. What I want I don’t know can be done. You can’t let us run the company. I know that for a fact, because we’d drive it into the ground, that’s a guarantee. “Ahh, what do you mean, books don’t come out on time?” You know what I mean? A lot of us just want to do comic books and the business end of it is whatever, so…I don’t know what the answer is. To tell you the truth I don’t even know if there is an answer. All I know is that the system that exists as it is right now, for some people — and specifically myself— just isn’t good enough right now.

GROTH: Has Malibu invited you to the office to talk to the staff?

MCFARLANE: Has Malibu? No. But I don’t work for Malibu, Malibu works for me.

GROTH: In that case, have you invited them into your office to talk to your staff?

MCFARLANE: Yeah, yeah, we’re buds, don’t you worry about it. If they got a gripe, I’m sure they’ll come to me.

GROTH: If you think that Marvel’s treatment of creators is wrong, and that it would be morally compromising to work for them, why would you be interested in seeing an Image/Marvel crossover?

MCFARLANE: Because the rules will change when we do an Image/Marvel crossover. I’m not going to go in there and go, “Yes! Let those 12 editors edit my stuff!” No no no no no no. It’d be more of like what Dark Horse did with the Predator/Batman deal. “Here’s the book; take it.”

GROTH: Except that Marvel would still be existing in its present state, still treating creators the way it does, and an Image/Marvel crossover would be making Marvel more money so it could continue to treat creators like that. So why would you want to be a party to that?

MCFARLANE: The only reason that I would be a party to that is, sometimes you can’t have everything, you know what I’m saying? The general public made me what I was. They bought my comic book. I think — again, maybe that’s just my own opinion — that within six months, the general public would love to see a Spider-Man/Spawn crossover.

I made my name on Spawn, I made my name on Spider-Man, we’re crossing them over. As long as I play somewhat within the boundary so that both of us are somewhat happy, then I’m willing to compromise some stuff to give back to the people who I feel are the ones who made me. There’s where I’m willing to control some of my emotions, to give back to the kids who I think I actually owe my entire living to. I think they’d like to see that project.

GROTH: So you’re saying you’d be willing to help perpetuate a system of injustice just to make millions of kids momentarily happy?

MCFARLANE: Uh … yeah, I guess that’s what I’m saying.

GROTH: [Long pause.] Hmm.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, it doesn’t make sense. I’m not saying that I’ve got the perfect game plan. I’m not saying you can’t bait me into a few corners. You’re doing a pretty good job of it here. You’re on your toes, and I really appreciate that. You actually sound more like my wife. She catches me every time. There’s one hypocrisy, boom! I get nailed. That’s good, you’re good.

GROTH: You left Marvel because you had ethical misgivings about them, and then you went to Malibu. Do you have any ethical misgivings about that?

MCFARLANE: Nah, not really.

GROTH: How do you react to the fact that Malibu was started by a distributor who was going out of business owing other publishers and creators money?

MCFARLANE: [Sighs.] You know, to tell you the truth, Gary, we weren’t even aware of that. So we just kind of went in there and we were happy and so some of the other stuff comes up … if you think that I haven’t talked to Dave Olbrich and Scott Rosenberg at Malibu, then you don’t know me very well. We’ve had our conversations and I’ve quizzed them on a few things. I’ve heard their sides of the stories. Both sides are fairly convincing. All I can do is be aware of both sides of the stories and just hope that history doesn’t repeat itself. Otherwise, what can I do, pull my services? I could find another publisher, but I’m sure I could dig something up in their closet too. I don’t know the full scoop of it, but we’re there. We didn’t go to Malibu to say “These guys are the coolest.” They just happened to be guys that said, “We want to publish your books,” and we said “OK.” We didn’t sit there and ask them for a history of their company, we just said, “OK, you guys publish comic books, you can do it, fine, we’ll subcontract you out to do it.” And that’s essentially what they are; they’re subcontractors for us. We could have picked one of 10 other companies.

GROTH: Did you ever think about putting pressure on them to get them to actually pay the people they stiffed?

MCFARLANE: Naw, not really. Like I said, I’ve heard both sides of the story. Everybody can justify why they do stuff, because otherwise it doesn’t really make sense why you do stuff.

GROTH: Marvel could justify its behavior, too, and you don’t accept that, so why would you accept Malibu’s justification?

MCFARLANE:What Marvel did was personally affecting me. Even though the system was wrong before I got there, I couldn’t do anything until I could see that the system was wrong, and then I went “You know, the system’s wrong … ” Maybe there’s something I could do and maybe I should, but I’ve got enough problems fighting my own battles.

If there’s a wrongdoing there, and there’s money to be had, the people who have been wronged should go after that and should fight that. That’s not my fight. I wouldn’t expect somebody to fight my fight. I don’t know what’s there, to tell you the truth. Maybe that’s my ignorance there. I just have a little bit of the black and white of it. I haven’t really pulled the layers apart. Our relationship is working right now, so who knows? That’s not my fight, I don’t think that’s my fight. I mean, I read your editorial, and if what you’re saying is true, then some of that stuffs not good, but they’re telling me a little bit different story, so it’s like, “Well, I don’t want to think that Gary’s a liar, and I don’t want to think that they’re liars … ” All I can do is assume there’s a misunderstanding, a lack of communication, and I don’t feel that that’s my fight right now.

GROTH: I’m sure all the publishers who were never paid by Rosenberg would like to hear how he justified not paying them to you.

MCFARLANE: That’s not really for me to say.

GROTH: No, it’s for them to say, but they’ve never said it.

MCFARLANE: Yeah. So that’s not, again, that’s not my fight. The best thing to do would be to phone them and get an answer out of them. I mean, I could nudge them.

GROTH: Yeah, maybe you should call them up and say, “Look, why don’t you call up the publishers you ripped off and tell them why you never paid them?” You know, you have that power, Todd.

MCFARLANE: You bet I do! Fuck, I got more power than … fuck, if people want to … they don’t know how much power I got, that’s what’s the scary part. They got to deal with this prick here called Todd.

GROTH: That’s right.

MCFARLANE: Yeah, you’re right. You’re right, I could do that, but ...

GROTH: The whole list of publishers is in the Journal, along with how much he stiffed us for…

MCFARLANE: Maybe somewhere down the line when old Todd … I mean, I got my own fights going right now, but once I’ve solved those I’ll go “OK, who else can I hate here?” and then maybe I’ll take that one up. “Buddy — let’s get this fucking thing cleared up right now to the satisfaction of everybody.” You know what I mean? I don’t like it, either. Unfortunately…call that a cop-out, I got other things that I’m battling right now and this is a preexisting thing that was there that isn’t why I’m at Malibu.

GROTH: Do you respect what Malibu publishes?

MCFARLANE: I don’t know. I’ve never seen any of their books.

GROTH: I see. Well Todd, don’t you think that if you want publishers to respect artists that artists ought to go to publishers who the artists respect?

MCFARLANE: I guess so.

GROTH: But you didn’t care what they published.

MCFARLANE: Probably … see, the reason we were there is because Rob was doing a book with them. He’d known Dave and he spoke highly of Dave and said, “Dave’s a good guy.” Not going, “We could’ve had 20 other guys,” but it was like Rob plugged for him, he said he’s a good guy. I said, “OK, fine. I respect Rob’s decision. If Rob speaks highly of that guy, it’s good enough for me.” I like Rob, Rob’s like a brother to me, so, sometimes you’ve got to trust other people’s opinions. I believed that he was a good guy. We were just looking for someone to help us print the comic book … I’m sure that’s not a very satisfying answer.

GROTH: Well, morally it’s sort of idiotic.

MCFARLANE: [Laughs.] Good one! Put that one in italics! “Morally idiotic,” that’s a good one. See, I like that, that’s a good one.

GROTH: Do you think there’s some truth to that, though? I mean, if somebody said “You know, like Marvel, they fucked over a lot of other people but they didn’t fuck me over so I’ll work for them … ”

MCFARLANE: Whatever.

GROTH: That seems pretty…

MCFARLANE: You know, Gary…

GROTH: I mean, the old “I’ve got mine, fuck you Jack” mentality. “They can fuck over everybody else as long as they don’t fuck me over.”

MCFARLANE: You know, I hate to say it, but there’s some truth to that. The more I read about everybody and their gripes, the less patience I have.