One thing about Mickey is that he is largely recognizable even when rendered in a fashion distant from the official Disney versions. His signature characteristics – particularly the shape of his head – enable him to circulate divorced from a particular graphic style. In akahon since the mid 1930s, Japanese comics artists had taken advantage of this situation, allowing them to use the image of Mickey without the look of Disney. I know of a few examples of this in postwar akahon, for example Yoshioka Ryūzaburō’s Doctor Strange (Kai hakasei), published in Nagoya in 1948.

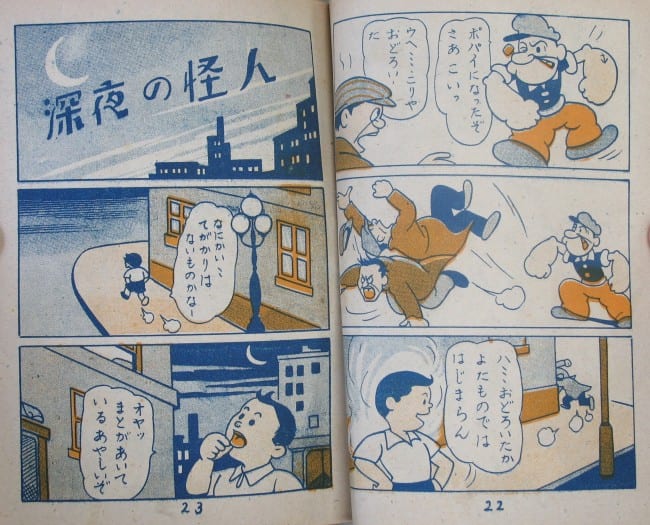

The story is an Edogawa Ranpo-type “youth detective” adventure, about a precocious boy who uses his smarts and inventions to break up a criminal gang, in this case one operating a robot to rob trains and banks. The amazing invention of this manga is a potion that allows the boy to transform himself into other characters at will: a woman when he wants to walk through town un-noticed, a giant gorilla when it’s time for a fight, and Popeye for the same purpose. Trapped at one point in a room whose walls are closing in to crush him, the boy transforms into a miniature Mickey rodent – looking like the one on the cover of Manga College – and jumps out through the high barred window.

Granted, a faithful rendering of Disney’s Mickey was not the artist’s goal here. Yoshioka was a solid artist with a sure hand, hired often by mainstream children’s magazines, and had he wished to make this mouse look more like the Disney version, he was certainly capable of doing so. The point is that he chose not to. For this artist, Mickey did not demand the respect of high production values. In fact, the narrative suggests that there is nothing especially special about him. He is one amongst a set of prominent but interchangeable comical Hollywood characters.

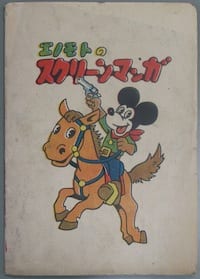

What I am showing to the right is the inside front cover of one of Enomoto Hōreikan’s “Screen Manga” books, a series the prolific Osaka publisher produced in the early 50s. As its title suggests, the series was designed to tap into the popularity of the movies, and did so by publishing work in genres like sword-fighting chanbara and the Western, but also by simulating some of the excitement of going to the theatre and seeing movies on the big screen. The series is a rich topic in itself, so just two details here. The inside front and back covers of each volume in the series are decorated with an array of movie, manga, and animation characters possibly meant to evoke the hand-painted movie-house sign or poster. Mixed in amongst them are Popeye, Olive Oil, and Mickey Mouse, who is looking the worse for wear – like a distant memory, or fan graffiti.

Mickey appears a second time on the back of the books, now dressed in cowboy garb, riding a horse, smiling with a pistol, much better composed, but still a pale image of himself. Appearing below the text “Enomoto’s Screen Manga,” he is made representative of this show. Clearly Mickey had staying power as an icon of laughter and a symbol of screen entertainment. These comics, however, are not particularly well drawn. The “Screen Manga” series has some interesting flourishes, but the poverty of draftsmanship and finish mark them stereotypically "akahon." Perhaps that is what Mickey is also standing for here: an entertainment ethic that does not privilege quality.

(Continued)