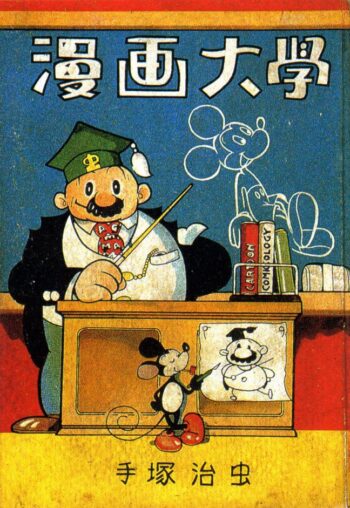

The original cover of Tezuka Osamu’s Manga College, which is no longer used for copyright reasons, can be read like a cipher, like a diagram of Tezuka’s artistic identity at around the time the book was published, in the summer of 1950. If you have read Manga College or similar intro books by Tezuka, you know that Professor Manga is basically a wizened stand-in for the artist. Here he sports a cap bearing the logo of Tezuka’s Mushi Pro, at this point just a name not an operation. He has drawn on the chalkboard a fairly faithful image of Mickey Mouse, as if this is where instruction in “Comicology” (the title of a book on his desk) shall begin and always return. Below on the ground is his partner. He is also modeled on Mickey. He has the big shoes, the ears, and generally the face, but he is definitely not Mickey. He is just a rodent. This impostor, this scrawny pot-bellied wise-ass wanna-be, he also makes art. He has drawn a picture of the professor, and it stinks.

What is going on here? Professor Tezuka is so good at cartooning that he can simulate Disney. Pseudo-Mickey is so bad that he makes a mess of Tezuka. This is not teacher versus student, for the students are sitting over here, on our side, facing the teacher and the board. So much is illustrated on the first page of the book, showing a standard college lecture hall, with tiered seats in a semi-circular arrangement, looking down upon the professor and, at his foot, the little mouse. How is it that the fake Mickey is Tezuka’s aide? Or conscience? How is it that he teases Tezuka with maladroit yet effective caricatures?

Is it that Tezuka draws the rodent as the rodent wants to be seen, while the rodent does just the opposite, rendering Tezuka as Tezuka wishes not to be seen?

How is this the face of Comicology in Japan, 1950? Is it significant that in that very spring Tezuka had begun his first serial for a Tokyo magazine, and that perhaps he could begin to look away from his akahon roots and the rodents living within them? Is it significant that just the previous year, Daiei Film Co. President Nagata Masaichi had signed a personal deal with Walt Disney to be the studio’s sole licensing agent in Japan, thereby bringing to Japan the first official Mickeys in bulk in well over a decade?

Thesis: From his arrival in Japan in the early 30s, Mickey Mouse was an icon of humor. To some, he was also ambassador of American ingenuity and American quality in production. But thanks to lax copyright protections for foreign properties, and his rendition by goods-makers that did not necessarily privilege the faithful or even skillful reproduction of his image, Mickey also became in Japan an icon of appropriation and its side effects, like modified personality and degraded design. This continued into the early postwar period. But towards the end of the Occupation, a series of forces colluded to “correct” Mickey’s image. Amongst them was Tezuka Osamu. For Tezuka, rectifying Disney went hand in hand with a number of things. It meant denying the akahon rodent of his roots and the production ethic on which its inventiveness fed. It meant recalling Mickey from appropriation and putting him back in the hands of authorship. It meant repositioning Disney as a light of genius and industriousness, against a mainstream that viewed him primarily as a talented showman and joker. It meant seeing himself more and more in the image of Disney. It meant expelling the rodent from the classroom, however much he had been there for the professor in his youth, and teaching straight from the Mickey on the board.

For what follows, let us take the rodent as akahon and the blackboard Mickey as manga industry at the dawn of the Fifties. This allegory, as you will see, is based on more than my imagination.

Note: On akahon, see “An Introduction to Akahon Manga”

(Continued)