One of the biggest blind spots in the scholarship on Tezuka Osamu is the assumption that his main access to Disney was through animation.

Granted, first contact might have been made watching Mickey alongside other American animation stars like Popeye and Betty Boop in theatres and at home in the 1930s. Wrote Tezuka in 1973 (roughly translated, here and throughout):

I liked Disney, I adored Disney, here before you is a man whose life was determined by Disney.

I first encountered Mickey around second grade at an animation festival [Tezuka was born in 1928]. Also my father brought home a rickety home projector called the Pathé Baby, and amongst the films he purchased was Mickey’s Choo Choo. From that point on I became attached to Disney by a chain that could not be cut.

And then from fascination to emulation,

I first followed the comics of Tagawa Suihō and Yokoyama Ryūichi. But suddenly, once I became devoted to Disney, I set out to copy and master that stuffed-animal style, eventually ending up with how I now draw.

But note that he does not specify what Disney media he “copied,” and nowhere does he say that he learned to “master” the Disney style on the basis of the animation alone.

Tezuka was a comic book artist first and foremost, his dreams and later successes with animation notwithstanding. And as a comic book artist it would only make sense if comic books were his strongest influence, which indeed they were.

In an interview late in life Tezuka said:

Speaking of myself, when it comes to comics, from 1947 or ’48, for the next fifteen or sixteen years, I was heavily influenced by American comics.

The word there is “Amerika manga,” which could mean any sort of cartooning. But then he makes clear that he is not referring to the superheroes, gangsters, or space adventurers of the pulp tradition.

Those American comics themselves were heavily influenced by Keaton’s comedies, Mack Sennett, those sorts of films from the golden age of comedy. The gagmen that appeared there, for example Roscoe Arbuckle or Ben Turpin, there were lots of comics that used their style, their faces just as is. Especially Chaplin with his bowed legs and over-sized shoes. Those sorts of features were used directly in comics. In that era, all American cartoonists imitated the stars of comedy. That is what I worked so hard at copying, and so that’s why my comics are bowlegged and big-shoed. At the level of content too I was deeply influenced by the strong social caricatures of Chaplin’s comedies, the tears mixed with the laughter. The biggest influence of all was the rhythm.

In his practice works from the war, particularly To the Day of Victory (Shōri no hi made, Summer 1945) one can find elements that seem to have come from the American silent comedy tradition, from pratfalls to overloaded Keystone-type fire engines. There are images of Jiggs and Maggie in similar scenarios, so perhaps that is the sort of comics he is referring to. But this manga is from 1945. What comics could have been in this “silent comedy” style after the war?

Wrote the artist in an article on Walt Disney from 1973:

Just after the war, more than half of the 10 cent comics the Occupation soldiers brought and read and then dumped were second-rate Disney. The same with animated movies.

The Japanese term is “Dizunii no aryū,” which could mean either “second-rate knock-offs of Disney” or “second-rate things by Disney.” Whichever the case, one assumes Tezuka is referring to the many Disney and roughly Disney-like things from Warner Bros., MGM, and Walter Lantz Studios published by Dell, “the world’s largest comics publisher,” as the company described itself (accurately) in advertisements of the early 50s. Dell might have matched Tezuka’s tastes, but considering the volume of titles and their print runs (some in the millions), Dell was also statistically the most likely comic book to find its way into Japanese hands.

Then he continues,

Around 1945, daily life might have been hard, but the reputation of Disney was at its highest. The voices of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck had stabilized, Snow White and Bambi were huge hits and had received a number of international prizes. It really was like the brightness of a rising sun. And then Japanese children after the war had no choice but to face the flood of Disney comics that accompanied the brainwashing of “American democracy.” That was their merit as propaganda against the Japanese.

Keep in mind that Tezuka says this twenty-some years after the fact. He voiced similar sentiments later, especially about Disney’s Latin American films and Carl Barks’ books. But they all come after the late 60s, after the Vietnam War had wiped out America’s reputation and revealed its foreign policy for what it really was, after Tezuka had become a middle-aged man writing adult manga tackling specific social and political issues versus the generalized Cold War fears of his 50s books. One might take from these quotes evidence of admission that the artist read American comic books copiously and studied them in detail. But the suspicions of them as ideological vehicles of Americanization, I think are a later accretion. It is one thing to criticize Uncle Sam. It is another to see Walt Disney as Uncle Sam, and the latter perspective did not come to Tezuka I suspect until much later.

From an art historical perspective, another caution should be exercised. As he says, the influence was heavy for more than fifteen years, from 1947 or so to 1963 or so. Presumably his models and the nature of influence changed over time, and indeed the manga themselves indicate that they did, from Disney-derived line work and figurative stylization between roughly 1945 and 1947, to a deeper interest in breakdowns and cinematic techniques beginning in late 1946 but especially after 1948, and a fuller adoption of a mixed-source sense of slapstick humor after 1950, at which point he also found a place for the American-style superhero. The period of most intense influence seems to have been the early 50s.

A contemporary glimpse of Tezuka’s immersion in comic books can be had in a back corner of the June 1951 issue of Manga Shōnen, where the artist was publishing his first major magazine serial, Jungle Emperor. In an endearing drawing for his fans of his workspace in Takarazuka, the happy artist sits snug at his desk surrounded by his workthings. Around him are bookcases and shelves and boxes stuffed with reader letters, drawing supplies, trash, manga magazines, his own books, a radio that does not work – and in two places – in a glass-faced cabinet to the right and stacked on top of small shelving unit holding finish artwork – are “Amerika manga.” From the shape of these books in their depiction on their left, this clearly means what you would assume it would mean and that is ten-cent comic books.

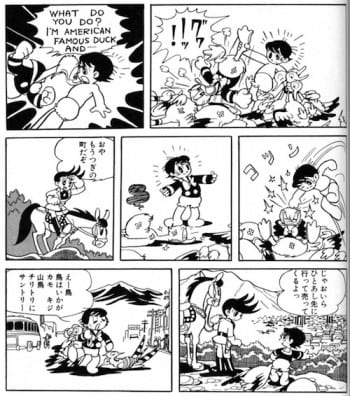

What was in the pile? The manga of this period provide some idea. This was the period that Tezuka created the Bambi-influenced Jungle Emperor, the L’il Abner and Popeye-stylized The Cactus Kid, and the Pinocchio and Mighty Mouse-conjoined Atomu. I know of multiple citations from Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories and the Disney Four Color series in his work of the late 40s. In an interview from 1979, he said he liked the original Captain Marvel. In the mid and late 50s, he would cite Dick Tracy, Batman, and Plastic Man. A perfectly drawn Donald Duck (shown above) makes a cameo in 1959.

His collection was large and growing.

(Continued)