Jack Jackson, aka “Jaxon, was a first-generation underground cartoonist. (In fact, with “God Nose,” which he self-published in 1964, he may have been the first UG cartoonist.) He was a fifth-generation Texan, born May 15, 1941, in Pandora (est. pop. 125). He died from a self-inflicted gunshot, on June 8, 2006, atop his parents’ grave in Stockdale (est. pop. 1519). He had diabetes, prostate cancer, and a neural disease which had left his hands too shaky to draw.

In 1966 Jaxon had come to San Francisco. He spent two years overseeing the posters for rock concerts promoted by the ex-Texan Chelt Helms, and then founded, with two other Lone Star ex-pats, the UG publisher Rip Off Press. After returning to his home state in the early ‘70s, Jackson began a chronicling of its past in comic form that would win him acclaim as a Lifetime Fellow of the Texas Historical Society and member of the Texas Institute of Letters. Posthumously, he was inducted into the comic industry’s Hall of Fame.

In 2012 Fantagraphics published in one volume “Los Tejanos/The Lost Cause,” two of Jaxon’s previously published graphic histories. Recently, with the presence of those Texans wrestling in the mud of the Republican presidential nomination process in my thoughts – and not unmindful of what what other Texans had done for the nation in the last 50 years -- I read it.

In 2012 Fantagraphics published in one volume “Los Tejanos/The Lost Cause,” two of Jaxon’s previously published graphic histories. Recently, with the presence of those Texans wrestling in the mud of the Republican presidential nomination process in my thoughts – and not unmindful of what what other Texans had done for the nation in the last 50 years -- I read it.

I

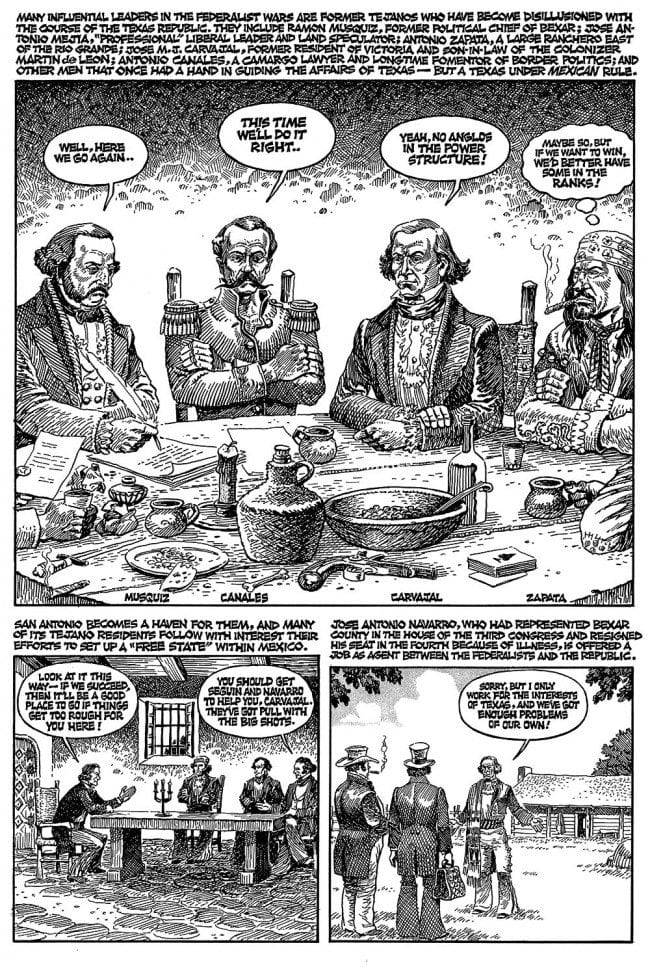

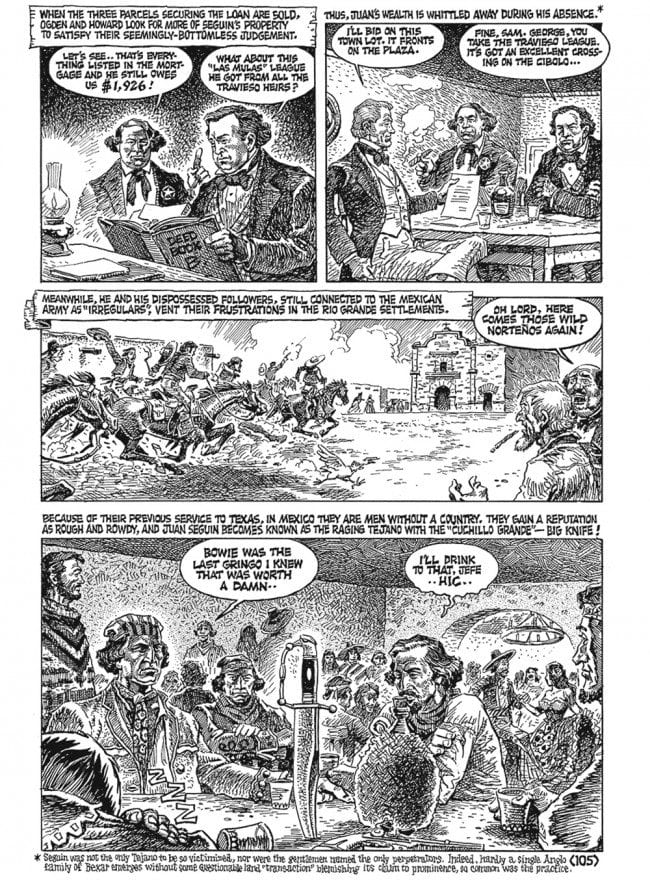

“Los Tejanos” begins in 1835 and ends in 1890. Its central figure is Juan Seguin, who fought in wars both for Texas against Mexico and for Mexico against Texas. Its political focus is Texas’s secession from Mexico, its winning of independence, and its union with the United States. Its larger story is of the exploitation and debasement of its native Hispanics by rapacious Anglos. “Lost Cause” begins in 1857 and ends in 1895. Its focus is post-Civil War Texas, concentrating on the effect of Reconstruction on Texas’s white population, overlaid by the story of the bloody Taylor-Sutton feud, and its most notorious participant, John Wesley Hardin.

The volume makes for an odd history, covering only 60 years and one portion of one state. In balance and content, it may seem unfamiliar to most readers. The fight for the Alamo receive’s a single panel’s attention. (Davy Crockett is, at most, an unnamed figure in a coonskin cap.) The Civil War begins and ends within three pages, while an afternoon get-together involving two extended families receives 20. Forgotten figures, once of consequence to, at most, neighborhoods, not nations, and commanding their attention for months, not decades, are unearthed and memorialized, often to the question at-what-benefit-to-human-knowledge-and-understanding come Martin de Cos, Cheno Cortinal, Doboy Talor, Jack Helm, Gen. J.J. Reynolds, Gov. E.J. Davis., Big Foot Wallace, Alljaw Smith?

But Jackson worked with passion and commitment and made his choices with reason. His research, the novelist Ron (“The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford”) Hansen writes in his introduction, was “extensive, loving and almost obsessive...” Though neither book is footnoted and contain only partial bibliographies Jackson clearly dove deeply into musty library stacks and cob-webbed state archives. He drew upon unpublished manuscripts and left-in-trunks memoirs. Old maps, archived photographs, and bundled letters absorbed him. He seems, however, to have adopted a somewhat tales-around-the-campfire approach to what he culled from them. He seems to have swallowed whole Hardin’s account of gun battles fought and number of men killed (70), while even Wikipedia suggests his claimed body count could be reduced by a third. And Jackson passes along the widely discredited story that the song “The Yellow Rose of Texas” was based on the beautiful light-complected slave girl whose presence in the bed of Santa Anna distracted him from properly overseeing the Battle of San Jacinto. (No evidence exists this was so, and, anyway, if Santa Anna was pre-occupied, it was by freeborn woman from New York named Emily.)

II

Jackson wrote and drew with an agenda. In “Los Tejanos” he persuasively argued the cause of Texans of Mexican ancestry. In “Lost Cause,” his case for Texas’s whites is less convincing. The Comanches, whose claim to the land pre-dated either group’s, are portrayed primarily as raiders and warriors in these books. (Jackson featured them in another, “Comanche Moon.”) Afro-Americans fare even less well.

When “Lost Cause” first appeared, a reviewer in “The Austin Chronicle,” an independent newspaper, attacked it as racist. Jackson defended himself in a lengthy interview in “The Comics Journal,” conducted by Gary Groth in 1998, which is included in this volume. (The review is not.) Jackson explained he had written the book from the perspective of Reconstruction era Southerners, an “oppressed” and “subjected people.” His position was that he could portray racists sympathetically ... (because) racism was just part of the day” and they “had the same hopes and dreams... (as anyone) of any era.” His mission, he told Groth, was to “take people back in a time machine... and let them see events as they occurred through these people’s eyes.” (Emphasis in original.)

I think it fair to say that Jackson would find himself even further out of step with progressives today than he was 17 years ago. In the interview, he brushed aside the suggestion that it would be inappropriate to name a new high school after Jim Bowie, a slave owner and slave runner, on the grounds that “everybody in the South” who could afford it owned slaves. (In fact, at Bowie’s death, in 1836, Texas had a population of 70,000 and, at most, 5000 slaves.) And while Jackson recognized that some might have been offended at his using the Confederate flag as the backdrop for “The Lost Cause”’s front cover, he does not suggest he considered it a bad choice.

Even when he was speaking with Groth, Jackson seems somewhat tone-deaf, foggy-visioned, and disingenuous. The fact is, he did not create either of his books, strictly speaking, from the point-of-view or in the voice of a 19th century Texan. Both presented as the work of a 20th century historian, which would seem to require an objectivity and balance, no matter how partial he was to one side or another, that is not always present.

While Jackson identifies Texas as a slave state, he never depicts slave labor or slave life, with one quasi-exception. He shows only one example of an Afro-American acting in commendable fashion, but several examples of them behaving poorly. This is defensible, I suppose, on the grounds that his narrative did not naturally call for the inclusion of such material. But in what he chose to include, Jackson made some questionable calls. He often visually depicted Afro-Americans in a stereotypical derogatory fashion, which he never did with poor whites. (I refer to the dice-shooting on p. 160; the flashily dressed, grinning figures on p. 162; the suggestion that only liquor motivated free men to vote on p. 216. The only other group he portrayed so negatively were the fat cats, robber barons, and pols, who might have stepped out of Thomas Nast cartoons.) Jackson could argue “Well, Negroes did shoot dice/dress flashy/vote in exchange for drinks”; but when there is little to suggest they could also behave with dignity or wisdom, such protest carries only so far.

Then there is Jackson’s ear. His reproduction of Afro-American speech is so replete with “massa,” “dawg,” “we’s,” “sho is” “suh,” and “dere be dat,” he might have been writing dialogue for a minstrel show. Maybe the people he portrayed did speak like this, but Jackson’s whites, no matter how ill-educated, consistently speak with better syntax and grammar. They never swear. They do not even have a Southern drawl. So he can not convincingly claim he was simply reproducing speech. He was characterizing in a prejudice-inflaming fashion.

(I could be wrong. You could argue that Jackson created “Lost Cause” from a hybrid 20th century historian/19th century racist point of view. That is, Jackson depicted most of post-Civil War Texas as neutrally as any historian. He researched; he considered; he concluded. Except when it came to Afro-Americans. There, he put on his page what was seen and heard in the racially warped perspective of the people who were his primary focus. His idea may have been that only if readers perceived as these whites perceived could their behavior be adequately considered. But that’s the best I can do in defending these portrayals.)

III

I found Jackson’s books most valuable in panel-by-panel consideration. He laboriously detailed the world he chose to document. Each saber, rifle, uniform, sombrero, main street, ranch house, courtyard, furnishing resonates with authenticity. His battle scenes excite. His social gatherings bubble. His legislative sessions reek with corruption. His renderings of even minor figures are so accurate that other historians can identify them before reading their names. His vistas capture a terrain that is vast and wild and calls forth the beast at some men’s core.

I found Jackson’s books most valuable in panel-by-panel consideration. He laboriously detailed the world he chose to document. Each saber, rifle, uniform, sombrero, main street, ranch house, courtyard, furnishing resonates with authenticity. His battle scenes excite. His social gatherings bubble. His legislative sessions reek with corruption. His renderings of even minor figures are so accurate that other historians can identify them before reading their names. His vistas capture a terrain that is vast and wild and calls forth the beast at some men’s core.

There is little flow between these panels, a condition enhanced by their tendency to often jump locales and years.) The eye does not skim or swoop across Jackson’s page. Instead it is apt to gaze upon each panel as if it was a canvas on a museum wall. In these contemplations , the greatest rewards of these books lie, though, as with any contemplation, the yield may have already lain within the individual engaged.

The Texas I saw revealed by Jackson, for instance, was built from theft, through force or duplicity, of others’ land. Fortunes were built from rustled cattle and purchased politicians. Power was amassed by banding together, as family or clan, federation, republic, state, or nation. It was maintained by organizing gangs and posses, regulators and protection clubs (like the KKK), private armies, bastardized “state police,” Texas Rangers, and, eventually, the military. It manifested through ambush, arson, assassination, castration, lynching, mass execution, and war. On an individual basis, if someone insulted you, or refused to drink with you, or was obnoxious, or cheated at cards, or came to arrest you, justly or not, you shot him. If someone was under arrest and you didn’t want to deliver hm to jail, or if someone was in jail and you didn’t want to await his trial, you shot him too.

That was 125 years ago. That is not so long. (I had grandparents alive then.) It was the culture which produced Hardin, the central figure, not only in “Lost Cause,” but in a surprising number of other books which Jackson drew upon. I found the degree of attention paid this man peculiar. For aside from the number of people Hardin slew, which even by Wikipedia’s reduced count exceeded the total of most contemporary psychopaths, he seems to have done nothing more worthy of interest than Alljaw Smith. (After serving 25 years in prison, Hardin did become an attorney, presumably before Texas required applicants to the Bar to provide proof of their “good character”; but there is no evidence his skill as a litigator was remarkable.)

In a postscript to “Lost Cause,” Jackson acknowledged that some might consider Hardin simply “a paranoid personality who enjoyed killing”; but he equated him instead to Theodore Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan. (This did not carry significant weight with me, since I have, at times, considered actions of both Reagan and Roosevelt insane; but even I would admit they had more marbles in their sack than Hardin.) It was Hardin’s presidential-like ability to walk softly and carry a big stick that Jackson admired. In Hardin’s case this was a six-gun that “he would not hesitate to use when his life and value system was threatened.” Well, “life,” okay; but value system? That could leave a lot of folks bleeding to death in the dirt because of medical procedures they performed, or cartoons they drew.

Jackson further suggested that Hardin was “just like us if we had the nerve to act on our convictions.” That is a sobering assessment, which seems to aptly, if unfortunately, expand the boundaries of the “Texas” under consideration. Certainly no one who reads the daily paper or watches the evening news can dispute the notion that there are many whose minds might move their trigger fingers as easily as Hardin’s. The distressing thing is that Jackson does not seem to recognize that the “nerve” he admires may stand for neuro-derangement and “conviction” may be a may be another word for “lunacy.” Otherwise, to be blunt, families can grow into nations and John Hardin into Ted Cruz calling for carpet bombing the Middle East. For civilization to advance, indeed for mankind to survive, there must be, instead, reason and compassion. Otherwise, Earth will become a single graveyard for us to self-inflict our own corpses upon.