I’m not sure to what extent I need to explain the graphic-novel cycle Cerebus to a Comics Journal audience. Hard as it is for me to believe, based on my conversations with younger cartoonists, it seems like some basic background might be advisable here. The history of this book and its author used to be a legend in the comics world — in fact, it reads a lot like a superhero origin story. In 1977 Dave Sim, a 21-year-old comics fan, whose only job had ever been working in a comics shop, began drawing his own comic book, a parody of/homage to Barry Windsor-Smith’s Conan, featuring as its hero the eponymous Cerebus, an avaricious, hard-drinking barbarian who is also an aardvark. Two years into the series, Sim took LSD for a week and a half, suffered what he described as a “nervous breakdown,” and had to be admitted to a hospital, where he was diagnosed as “borderline schizophrenic” (whatever that might mean as applied to someone coming down off several days of acid). Recovering from this experience, he had a life-changing epiphany: Cerebus would run for 300 issues. It was a vast story; it would be his life’s work. Deranged hubristic ambitions are not uncommon among schizophrenics, people on LSD, or 23-year-olds, but here’s the remarkable part: He actually did it. Dave Sim drew Cerebus, putting out an issue a month, for the next 25 years. He finished it in 2004. It runs to 16 volumes, and occupies a solid foot of shelf space.

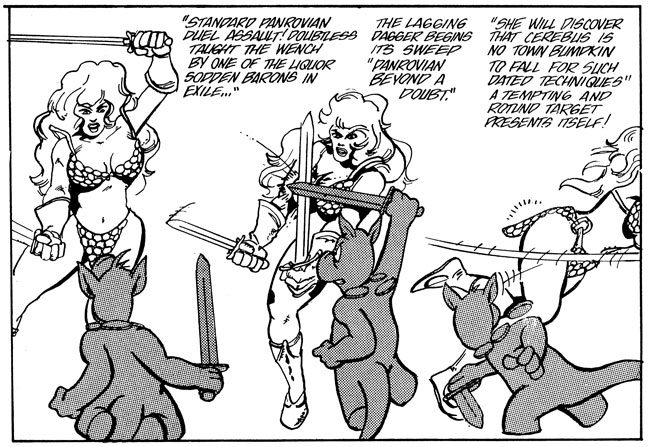

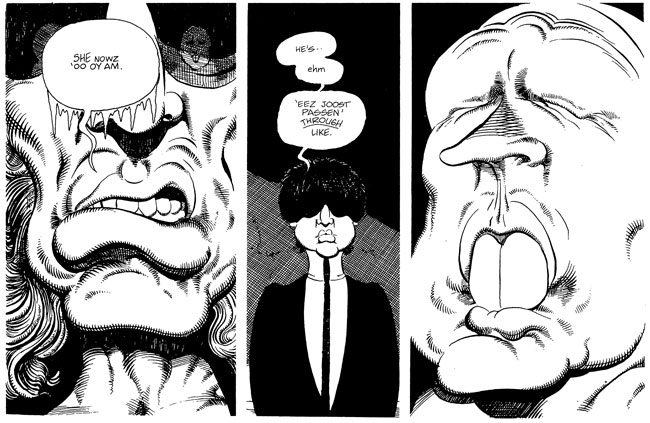

In the early, sword-and-sorcery issues of Cerebus, Dave Sim drew about as well as the second- or third-best artist in your high school, the guy you’d ask to do the cover for your heavy metal band’s album or airbrush the side of your van. After drawing about a hundred issues, by the time he’d finished Volume II of Church & State — around the same time he hired a brilliant and apparently indefatigable draftsman named Gerhard as his background artist, freeing himself to concentrate exclusively on his characters — Dave Sim had become one of the best cartoonists in North America. And not just in the excellence of his technical skill — he was relentlessly inventive and virtuosic. His exuberant formal experimentation extended from his lettering and paneling to the design of whole issues: Readers puzzled and wowed over the issues in which each page’s background was a fragment of one large picture of Cerebus, or the spinning of an ascending tower was reflected by the page layout rotating several degrees on each page, so that you had to slowly turn the whole book 360º in your hands in the course of reading it. “Thou shalt break every law in the book,” was his injunction to himself.

Sim was also a smart and voracious autodidact (he dropped out of high school after grade 11), and, as he matured, his intellectual passions grew beyond comics, and his artistic ambitions far beyond parody. The single-issue stories expanded into longer and longer story arcs, gradually growing into full-length, 500-page novels. As he continued drawing Cerebus, Sim incorporated everything that captured his interest into the book: He became interested in the mechanics of electoral politics, and Cerebus ran for Prime Minister; he got interested in the history of religion, and Cerebus became the Pope; as Sim’s literary tastes became more sophisticated, Cerebus encountered incarnations of Oscar Wilde, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway. He insatiably appropriated not only literary, historic and political figures, but fictional characters and screen personae, the likenesses of friends and colleagues, other authors’ prose styles, even another cartoonist’s dialogue in a manner that would’ve been called postmodern if he’d had an MFA. He wrote books within books, invented intricate political ideologies, created whole cosmologies. Throughout all of which the book’s central character remained the same anthropomorphized aardvark.

It also, against what might seem like any reasonable expectations, became a success. Dave Sim was one of the first cartoonists to publish his own work, and he was a vocal proponent of self-publication as the only means of securing artistic autonomy and control. Not only did he actually make a living being a cartoonist, he made it look glamorous. The monthly “Note from the President” and the photo that accompanied each issue of Cerebus hinted at a life spent doing nothing but drawing his comic book, smoking pot and going out (and breaking up) with good-looking girls. At comics conventions, he showed up in limos, rented out whole suites, threw parties. He’d become an alternative-comics rock star. He appealed to the young and unformed in much the same way as Jim Morrison or Hunter S. Thompson, artists whose personæ are at least as compelling as their work.

But then somewhere in there, roughly two-thirds of the way through the series, Dave Sim began to develop some let’s call them idiosyncratic and controversial views on the sexes, politics and religion — about which more later — all of which found explicit expression in his work. These “rants” and “tangents,” as he called them, alienated a lot of his audience. Quite a few of his readers would tell you that he went insane before their eyes. By the end, Cerebus’s circulation had dropped almost in half from its high point, circa Church & State — although that might also be attributed to the more static and internal action of the later books, or to changes in the business and culture of comics. The final issue, which showed the title character dying “alone, unloved, and unmourned” in fulfillment of a prophecy made back in 1988 (so this isn’t exactly a “spoiler”), completed an undertaking that began as an in-joke and ended as what its author, a man not given to modest understatement, claims is “the longest sustained narrative in human history.”*

Dave Sim noted ruefully that the completion of his vast project was met with “the sound of one cricket leg chirping.” Gary Groth, editor of the Comics Journal, which had had a combative history with Sim, sent him a note of gentlemanly congratulations of the sort you might imagine Holmes sending to Moriarty after the unexplained disappearance of the crown jewels. There were mentions in The Village Voice and The Onion’s A.V. Club — mentions that tended to take the same tone of straightfaced, whatever-else-you-wanna-say-respect the media pays to achievements like a record-setting win at the national hot-dog-eating contest.

It’s true that Cerebus occupies an oddly provisional place in comics’ canon, given the sheer magnitude of the project, its stylistic innovation and virtuosity, and its influence on other artists. (It was conspicuously excluded from The Comics Journal’s list of the 100 Greatest Comics of All Time.) It hasn’t helped Sim’s critical standing that he belongs to a cartooning tradition that’s currently unfashionable in an era of hip minimalism and the amateurish DIY aesthetic. His artwork is part of a lineage of densely detailed, illustrative, caricature-based cartooning, descended more directly from the fine art of William Hogarth and Honoré Daumier than are most contemporary American comics, a style whose modern masters are the likes of Arthur Szyk and Mort Drucker (and of which this writer is a marginal practitioner).

Cerebus is also too much a product of, and too narrowly concerned with, the world of comics ever to become the kind of breakout critical or commercial success as, say, Maus, Fun Home or Persepolis. Anything you can’t even begin to describe without explaining, “It’s sort of like Howard the Duck …” is never likely to get discussed in the New York Review of Books. Its parodies of characters, creators and trends in the world of comics circa 1980-2000 date badly, and were never even comprehensible, let alone of much interest, to anyone outside that marginal subculture.

But the main impediment to Dave Sim’s literary reputation is Dave Sim himself. His regressive social and political views and obnoxious rhetoric have created a public persona that’s eclipsed his artistic achievement in the comics world much more completely than it would have in the larger, less insular artistic world — where, for example, plenty of people call John Updike a chauvinist but not even his bitterest detractors question his mastery as a prose stylist, where Karlheinz Stockhausen’s ill-advised statement about 9/11 being a work of art didn’t get him ejected from the first rank of postwar composers, and artists like Wagner and Pound are still secure in their respective pantheons despite having endorsed ideas that are, to put it charitably, pretty well discredited.

But Sim’s controversial ideas are not peripheral to his work; he ultimately makes them its central message and purpose. Wagner never actually wrote any operas about the villainy of the Jews, nor Pound cantos praising the wise and just rule of Franco, but Sim incorporated his screeds about women and the tenets of his one-man religion into the text of his novel, so that even a reader determined to ignore all the apocryphal gossipy bullshit accumulated around the artist and concentrate on the work itself is finally forced to confront the fact that the man has some bizarre ideas and an abrasive way of expressing them.

Perhaps most damagingly of all, Dave Sim is the single most passionate and outspoken advocate of his own work, and also its most reductive and unreliable interpreter. Having finished his magnum opus, he seems unable to let go of it, and continues to hand down authoritative misreadings of the work that do it a serious disservice. He tries to rationalize the kinds of inconsistencies and contradictions that are only inevitable in a work that was written month by month over 30 years; he issues contemptuous dismissals of (female) characters who might have seemed to the reader to have had some depth and complexity; and he sometimes makes assertions that are clearly contradicted by the text. It raises the troubling possibility that what seemed like Cerebus’s literary quality may only have been so much projection on the part of its readers. What’s more likely is that Sim, like a lot of artists, is less than fully conscious of what he’s doing and is the last person who should be consulted about the meaning of his own work.

Sim’s loudmouthed self-promotion and self-pity has effectively divided comics readers into two camps: those who sigh and make the little twirly-motion at their temples when his name comes up, and a devoted core of fans so uncritical and defensive you’d have to call them acolytes, which doesn’t tend to do an artist’s critical reputation much good either. (Ayn Rand and L. Ron Hubbard have both become cult figures among different genera of dingbats, but Atlas Shrugged doesn’t get discussed in the same academic circles as the Tractatus, and you aren’t going to see a Library of America edition of Battlefield Earth anytime soon.) He complains that his work is willfully ignored by the comics world, but blaming his ostracism on the Marxist/feminist/homosexualist axis (this is not hyperbole) hasn’t persuaded many people to take a second look. And for all his plaints about his obscurity, he’s also been perversely obstructionist toward anybody who’s tried to publicize his work. (I’m thinking specifically, though not only, of the I-know-you-are-but-what-am-I stance he took toward the [female] interviewer for The Onion’s AV Club.)

It’s a situation I had hoped to go some small distance toward remedying for a new generation of readers who may not even have heard of Cerebus, or have heard of it only as an artifact of mental illness, a companion piece to accompany the story of Dave Sim, a very gifted cartoonist who went around the bend. Sim may well be a wackjob or an acid casualty, but he is also, I would argue, one of the greatest living cartoonists. And Cerebus is more than a curiosity; it’s beautifully drawn, intermittently hilarious and brilliant, the gargantuan and astonishing life’s work of a master craftsman.

That, however, was before I’d actually read the fucking thing.

• • •

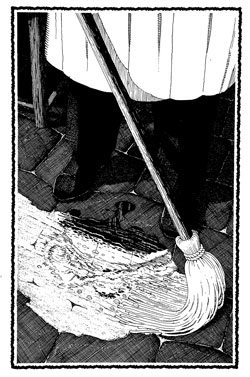

I read several issues of Cerebus over my college roommate’s shoulder back in the mid-’80s, which, fortuitously, happened to be the era of Church & State II, one of the artistic crests of the book. (Of course it’s possible that everyone’s favorite era of Cerebus coincides with their initial discovery of it — cf. Peter Graham’s adage that the golden age of science fiction is 12.) Dave Sim was one of the very few artists I ever deliberately studied (as opposed to the deep influences I unconsciously absorbed from, say, Mad magazine and B. Kliban): I marveled at his drawings of a hand blurred as it shakes out a match or a face reflected in a rippling puddle of mop water; I imitated the fine hatching in the wrinkles around Bishop Powers’s shouting mouth and internalized the lessons of his expressionistic lettering and word balloons.

I never did get around to reading Cerebus, though. I’ve always had it jotted down somewhere on my life To Do list that someday I’d have to read the whole thing. The glimpses I’d gotten through my sporadic reading were intriguing but also daunting; I was intimidated by the book’s sheer length and evident complexity, all the backstory I’d have to absorb just to have any idea what was going on. I wasn’t looking forward to having to get through all the amateurish fan art and dweeby allusions in the first volume, which veteran readers glumly assured me would be necessary to familiarize myself with the basic cast of characters and background. I decided to wait until Sim had finished the whole 300-issue run and then, I told myself — envisioning this in a comfortably distant future — I’d sit down and read them all in one marathon, War and Peace-like binge.

Which is what I finally did last summer. I traded one of my original cartoons for all 16 volumes of Cerebus and hauled the whole 20 pounds of it down to my Undisclosed Location on the Chesapeake Bay, where I holed up, away from the distractions of the Internet or girls and read them one after the other on the couch, listening to old soundtracks on vinyl and eating Old El Paso tacos, all pretty much while wearing the same T-shirt.

So, what are we to make of this thing, Cerebus? It’s far too long and complex to give it the kind of close reading it deserves even in the generous space I’ve been allotted here. Its sheer unwieldy scale makes it difficult to evaluate critically; it’s such a vast structure that it’s hard to grasp its architecture. And everything we know about its eccentric author makes it hard to see clearly as a work of art. What I want to try to do is clear away enough of the clutter of extraneous baggage it’s accumulated and step back far enough from it to begin to figure out what kind of book Cerebus is, whether it’s ultimately any good, where it belongs in comics’ history and canon, and whether it’s deserving of — and capable of withstanding — critical attention from the larger artistic and literary world.

*Not sure whether there’s any point in quibbling with a claim this arbitrary and ill defined. Is Cerebus “longer” than, say, Henry Darger’s 15,000-page illustrated novel The Story of the Vivian Girls? Or, for that matter, than Japanese epics that ran for a hundred volumes and took decades to compose, or soap operas that began in the ’50s and are still running today? How to compare the length of graphic vs. prose novels, let alone print vs. electronic media? Let it suffice to agree with Sim that his achievement is, by logistical measures alone, very impressive indeed. Just in terms of the dedication and discipline necessary to such an undertaking, and the 10s of thousands of hours of labor involved, it is awe-inspiring.

(Continued in issue 301)