Shimada Kazuo played a small role in the history of Japanese comics – Tatsumi Yoshihiro says he got the basic idea for Black Blizzard of two handcuffed convicts on the run from one of his stories – but not that small. Who was he?

Shimada, before he became a writer of detective fiction, was a reporter for The Manchuria Daily News, the leading newspaper in Japanese colonial Manchuria. He was born in Kyoto in 1907 and raised in Dalian, on the Liaodong Peninsula in northeast China. The Manchuria Daily News, which he joined in 1931, was owned by a subsidiary of the Southern Manchurian Railway, a semi-public enterprise at the forefront of colonial expansion. Over the next ten years, Shimada wrote for various departments, longest as social reporter, posted throughout Manchuria and for a stint in Shanghai, and as correspondent for the Kwantung Army. For his work he traveled widely across Japanese territory, from the Heilongjiang River in the north, to the Malay Peninsula in the South, and Chahar in Mongolia in the west. What he witnessed was not always pleasant. “I have seen most of the ways people can die. For example, someone flattened by a steamroller, and someone’s head rammed into their torso by a falling elevator. Many times I have seen bodies in pieces after a plane crash. That was during the war. So I don’t really like writing about scenes of death in my own fiction,” he says in an interview in 1957. “Do you find it scary?” he’s asked. “No. That’s why when I read these creepy murder scenes in detective fiction, they always feel fake.”

Shimada had no intention of becoming a fiction writer. He had read New Youth (Shinseinen) under orders from his editor, its crime and mystery stories – mainly Japanese and British in translation – assigned to reporters as models of snappy modern prose style. He had published some fiction in Manchuria, but without a thought of making a career of it. In 1945, he was reassigned to Tokyo. When the war ended, and Japan was divested of its colonies, The Manchuria Daily News naturally was liquidated. He was kept on for a time with clerical clean-up work, meanwhile distributing news to worried families about the situation in the former colonies on the continent and helping to find jobs for repatriates. Then in 1946, Shimada found himself without work. It was mainly for the prize money that he submitted a story to The Jewel (Hōseki) that year, a purse he claimed with a short story about Tokyo police detectives who unmask a homicide set up to look like a suicide. He continued to contribute to the magazine during and after the Occupation, and as The Jewel became Japan’s leading venue for mystery, detective, and later hardboiled fiction in the '50s, so Shimada became one of the country’s top authors in those genres. He published also in many other publications, from Kōdansha’s King to short-lived kasutori “pulps” like X, Spider, and Liberal, as well as boys’ monthlies like Shōnen Gahō and girls’ equivalents like Shojo. In 1951, Shimada won his first major literary prize, for stories from the previous year about crime-cracking newspaper reporters. In the '50s, many of his stories would star detectives from the Tokyo police, then later doctors and lawyers meddling beyond their job descriptions. It seems he never really went in for the private eye.

Shimada was classed as “honkakuha.” Meaning “the real deal,” as in “true” detective fiction, this term originated as Edogawa Ranpo’s name for the Golden Age of British detective writing in the 1920s and '30s. It was used mainly in contrast to spy novels and hardboiled American material. The name fits Shimada partially. In the mid '50s, he recalled being a fan of Conan Doyle and S. S. Van Dine via New Youth while in Manchuria. He came to admire Raymond Chandler, Graham Greene, and William Somerset Maugham after becoming himself a fiction writer. However, the defining influence was clearly his own fifteen years of experience as a journalist. Aside from his reporter protagonists, there is a professional sobriety concerning motives, forensics, and the dead in his writing, always simple and to-the-point, rarely at a fetishistic level of detail. The speed at which he wrote – a story a week, sometimes a night – and the brevity of his style he himself attributed to his newspaper training.

Considering his time in China, it is not surprising that the continent and its peoples appear with fair frequency in Shimada’s early fiction, typically in the most unsavory places. Criminals and victims alike are oftentimes linked to drug cartels and black marketeering with roots in China, Singapore, or the South Pacific. The backstage of crime in Shimada’s “White Street Slasher” (1950) is a Chinese restaurant in Shinbashi. That the victim had been there earlier in the night the detectives know because of the Chinese food and liquor found by the coroner digested in his guts. More steeped in Japan’s colonial past are bars like Rosa, from Shimada’s “The Ginza Murder Case” (1950): “On the face it seemed a typical Russian-style cabaret, but if you flipped it over you’d find a miniaturized version of all the vices of the continent,” with exotic bar décor from the Caucasus, naked beauties dancing to the music of aging violinists, and heroine and morphine addicts lying around “like raw tuna” in the back. It was “one of those seedy establishments for which Harbin was famous, transplanted as is, peddling voluptuous dreams.”

Sometimes the protagonists are hikiagesha, “repatriates” from the continent whose lives have been uprooted and ruined by the war. Such is the case in Shimada’s “Black Rainbow” (“Kuroi niji”), first published in King in 1950, then reprinted in a supplementary edition of The Jewel in 1953. The pianist Takiguchi, sent to fight in Manchuria just before the war ends, has spent the last four years in a Russian labor camp in Siberia. Severe frostbite has ruined his fingers and dashed his dreams of musicianship. Days after returning to Tokyo, he is framed for murder. Now he finds himself handcuffed to the gambler Kurokawa, who has his own post-Manchuria misfortunes. He came home from military service after the Manchurian Incident in 1931 to find his wife and daughter gone. As a man with a criminal record, he was treated like dirt in the military: no medals, no promotions, nothing but time in a punishment cell. Everyone back home thought he must be a traitor. Unable to bear the shame, his wife fled with their daughter and returned to her parents.

The story opens with these two ex-soldiers fleeing from the law after a train crash, which itself is described like something Shimada might have seen himself in his time as a reporter – “men and women covered in mud started crawling out of the wreck . . . wriggling around like worms . . . a woman’s arm reached out, but stayed stuck straight up into the air, motionless” – and probably inspired by the series of unexplained train derailings in Japan in the summer of 1949, big news at the time as supposed acts of Communist sabotage and Occupation era red-baiting. Similarly, Shimada’s pianist would have been understood at the time as a “red repatriate” (akai hikiagesha), one of the hundreds of thousands of Japanese detained by the Russians and indoctrinated with Communist propaganda. A large number returned to Japan in the summer of 1949 and immediately faced the hostility of the moment’s strident anti-Communism. The pianist’s politics do not come up, but the reputation of “red repatriates” for being “argumentative” probably lurks behind Takiguchi’s self-destructiveness – he drinks until he blacks out and buys sex in anger at lost love – just as his wrong arrest and scapegoating is probably informed by the social ostracism of returnee soldiers in postwar Japan. These were not passing issues for Shimada. Once questioned himself by the Counter Intelligence Corps for his involvement with postwar repatriation activities, and someone who probably thought of Manchuria as home, he certainly had a personal interest in the fate of Japan and China in the developing Cold War. While Asia usually appears as little more than exoticizing detailing in his fiction, genuine sympathy for the human remnants of Japan’s colonial past (or at least for the repatriated Japanese national) comes out in a story like “Black Rainbow.”

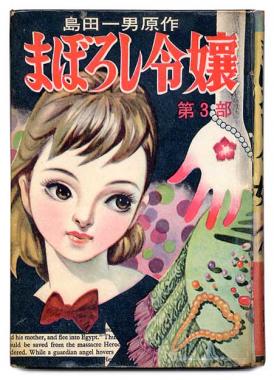

In his lifetime, Shimada saw a large number of his stories made into movies and television programs. The greatest flush was in the late 50s and early 60s, most famously Crime Reporter (Jiken kisha), a television series that aired on NHK for eight years between 1958 and 1966. If the Movie Walker site is correct, there are 44 films based on his work just between 1950 and 1966. There are also some manga adaptations. I know of four in which the author is explicitly credited: Takeda Shinpei’s version of Shimada’s youth murder tale Phantom Daughter (Maboroshi reijō, 1951) for the kashihon publisher Kinransha in the mid '50s, two volumes published by Shūeisha between 1958-59 based on the TV program Crime Reporter, Shirai Toyoshi's serial He Shines his Gun (Kenjū o migaku otoko, 1959) for Hinomaru bunko's Gekiga Magazine beginning in late 1967, and Iwai Shigeo’s single-volume The Man who Laughs at the Dark (Yami ni warau otoko, 1963) also for Hinomaru in 1968. Considering Shimada’s popularity in general, including his frequent contributions to youth magazines in the early and mid 50s, one suspects that there are more, credited and authorized or neither.

(continued)