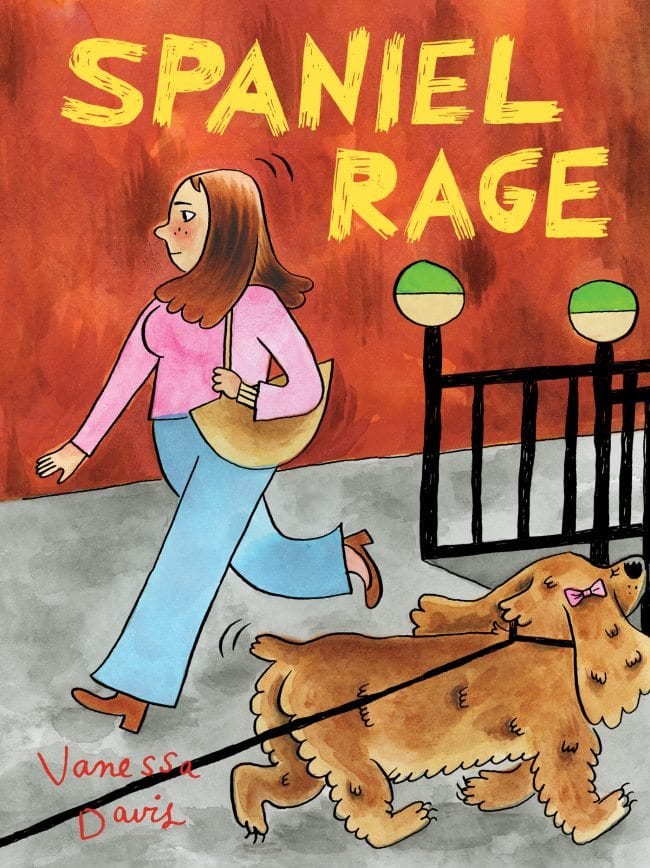

Since the 2005 publication of her first book, Spaniel Rage, Vanessa Davis has established herself as one of contemporary comics’ most reliably satisfying storytellers. Beginning her career with minutely observed, highly episodic diary comics about her life as a young woman finding her way in New York, her work has, over the past decade, grown ever more ambitious and intricate, without losing its attention to small, telling interpersonal moments, its gorgeous use of color, and its carefully calibrated combination of humor and poignancy. (Full disclosure: we’re also been good friends for a number of years.) Now, with the reissuing of Spaniel Rage by Drawn and Quarterly, I spoke on the phone with Vanessa—who is this year’s recipient of the Paris Review’s Terry Southern Prize for humor writing—about how her comics have changed over time, her experiences as a cartoonist, and what she’s working on now. — Naomi Fry

“I Definitely Felt Like a Baby”

Naomi Fry: Spaniel Rage initially came out in 2005. You weren’t really a professional cartoonist yet when you were making the comics that became part of the book. How did you start out?

Vanessa Davis: I definitely wouldn’t have called myself a cartoonist at that point. I studied art in all of the colleges that I went to and I had gone to this arts magnet school from seventh grade onward, so it had always been a really big part of my life and identity, but I hadn’t really settled on a niche; my niche had eluded me. At the point that I started making comics, I was working at the folk art museum in New York and I wasn’t making any art and so it was a moment where I was like, “Am I an artist? Do I do anything now that I’m not in school and don’t have to?”

And you were like 25 or something?

Yeah, I was like 23 or 24. I think Spaniel Rage itself came out when I was like 26.

That’s pretty young.

Yeah. [Laughs]

Now it seems like being a baby to me. To be 25.

Me too. I definitely felt like a baby, that’s for sure.

Did you really? Sometimes when you’re younger you feel like there’s this sort of false, or misdirected bravado of like, “I know everything, I know how things work.”

I think that there are 25-year-olds who do, or at least are like the kind of people that eventually do—I didn’t. I just felt like as much experience as I kept piling on, the thing didn’t happen where I was like, “I really know what’s going on in this world.”

I think that there are 25-year-olds who do, or at least are like the kind of people that eventually do—I didn’t. I just felt like as much experience as I kept piling on, the thing didn’t happen where I was like, “I really know what’s going on in this world.”

Do you feel similarly now?

No, I feel—I mean I don’t feel like I really know what’s going on, but I’ve sort of reconciled myself to realizing that this is like my personality type. I’m a wide-open person [laughs].

Sometimes there are advantages to not knowing anything. When you were first starting to make these comics that ended up being collected in this book, you weren’t part of a community really, so did you know what you were up against? Did you know the kind of power structures that were in place? Because every community has its own kind of rules and limits and figureheads and all of that. Were you at all familiar with any of that at the time?

No. I knew of some cartoonists and I thought it would be cool to meet them, or for them to like my work, and I also knew that there was a wide world of exciting cartoonists that might become my peers. So I looked forward—but I didn’t know. That was just so far away from what I considered my goals were at that point. I just wanted to see if comics would work for me as a medium, and I wanted to see if it would be sort of socially satisfying.

You mean to meet with other people who are likeminded?

Yeah. You know, I grew up on ’80s movies and also I had gone to this really bohemian high school. So I just imagined that college would be more of that and it wasn’t. And so I was still waiting to meet all these exciting people.

Yeah, it’s like you think, “Oh, I’m an adult, I’ll have these strong friendships with these fascinating women, and like exciting love affairs with these mysterious men.” Then it’s like: Brad Goldstein? [Laughter] And you’re like, “oh.”

Exactly. It usually falls short of the fantasy that you have. Also, my college years were really interrupted because I transferred a lot and I went to three different kinds of school [Washington University in Saint Louis, MICA in Baltimore, and the University of Florida]. So that probably played a part in me not figuring out what my favorite medium was or what my artistic niche was. I loved painting, but it didn’t really fulfill everything that I wanted to do, and I was studying textile design and fibers, but that also kind of fell short somehow.

Why do you think they fell short?

With painting, what I saw was that the real painter’s painter is into the almost sculptural aspects of painting. And with textiles I had a good decorative aspect to my approach, but it definitely wasn’t masterful and I really wrestled with the precision of actual textile design. Then, when I was at MICA, I did this one piece where I learned how to do freehand machine embroidery and I did all these different kinds of chairs, and I remember my teacher, who in general seemed pretty unimpressed with me, was looking at them and she was like, “You know, all these different chairs seem very narrative. It seems like these chairs should be in a scene and there should be something happening around them.” And I think that’s where my substance lies — in the narration. So when I would try to do something that was merely stylish, it fell flat. Or when I tried to be a craftsperson, it kind of fell flat. But one thing that deterred me from ever thinking about comics was the verbal aspect. One thing I liked about painting and making these still images is that I could talk about my life and sort of elevate the stories, by merely portraying them as images. I could make them seem substantial and interesting without losing peoples' attention, like I did when I would talk about my life. The literal narration in comics kept me away for a long time.

“Learning What Works”

So you started making what ended up becoming the Spaniel Rage comics in notebooks, on the subway on the way to work, and at home.

Yes. I thought, '”I’ll draw something and I’ll write something, and I’ll teach myself how much to write. I’ll see if it becomes anything, and maybe it’ll evolve.”

It really sounds like a self-education in a way.

Well, everything kind of worked in my favor. I didn’t have this lifelong desire to even be a cartoonist, so it wasn’t like I could fall short of any of my own expectations. And there was no pressure, because I didn’t know any of the people, I didn’t know what I wanted it to look like, and there was no danger of money or fame. With the fine art world, coming out of college, it was clear that you had to schmooze, you had to present yourself a particular way, you had to get your artwork beautifully photographed in slides, and you had to know all the people you had to send them to. Just all of this high-pressure shit that I was completely alienated by. And with comics, what I imagined is that all of the people at the comic shows were like my age or middle-aged people with jobs that did this as a hobby, and they had their little side life that was fun and kind of humble, but worked with the rest of their lives. So it wasn’t intimidating in any way.

There’s something about these comics that’s winningly modest. It’s not really trying to impress anyone. Sometimes you have these moments where you’re like, “I didn’t draw this so good.”

It would be disingenuous to say that it was just for myself and I never imagined anyone seeing it, but I couldn’t imagine that that many people would see it. And the people who did see it, I wasn’t too worried about their judgment.

How did these comics make their way from your notebook to the world?

I worked at the publications department of the Folk Art Museum and it was a really supportive office. The guy who worked in the mailroom knew all about my comics and my boss knew all about it. My friend who was the production editor helped me lay them out in QuarkXPress. And then I printed it out on the Xerox machine and stapled it and brought it to shows. I started making some friends and we had this weekly get together, and so I started getting to know some cartoonists more and I would hear gossip and learn about other cartoonists and I would see other people’s comics. And I started going to some more shows, like SPX in Maryland, and then I started going to APE in San Francisco. And I just figured that I would keep self-publishing these comics and just keep living my life, and maybe if I kept doing it for several more years I’d approach a small publisher and be like, “Maybe you’d like to put together a Spaniel Rage collection.” But what happened is that I started to be in a couple of anthologies and so I just … comics is a pretty welcoming community. Sammy Harkham showed my comic to Alvin Buenaventura’s wife and she really liked it. And so then Alvin contacted me about publishing it. And I was just shocked, because at that point the only people who were published were established or famous cartoonists; like, being published itself was a mark of being established. And so I wasn’t sure if I was ready for it, but I just decided, like, you wouldn’t say no, so I did it.

How do you feel about Spaniel Rage now that it’s being reissued by Drawn and Quarterly, more than a decade after it was originally published?

The thing that I love most about Spaniel Rage is that it speaks to the wide-open possibilities of comics; that they’d publish something so inexperienced and raw. Both the fact that Alvin published it, that people liked it, and that now Drawn and Quarterly is rereleasing it, because I think in most other art forms what’s celebrated is being a master and knowing what you’re doing and doing it really well. For me what I think is really being revealed in Spaniel Rage is that process: the process of learning how to draw or learning what to write about or learning what works, and what’s funny and what’s not, and what’s deep and what’s shallow. Basically, what I was impressed by with comics in general was the wide-open possibilities of the forms they could take. And then Spaniel Rage being published kind of confirmed all of those impressions, because I was such a newbie.

“This Practical and Romantic Thing”

Did you have a fantasy that publication would change everything about your life?

I mean, sure I had that fantasy, but I also couldn’t imagine in what way it would. Nothing really changed. Well, that’s not true. I definitely had a lot more exposure to other cartoonists and I got a lot of really good feedback and I enjoyed being the new pony [laughter] and it was like a party. I got a lot of attention and that was really fun, and that was pretty much it. I didn’t really know how to parlay that into the next thing. And I started dating Trevor [the cartoonist Trevor Alixopulos], my boyfriend, right after the time that Spaniel Rage came out, and so that was also a big disruption, where I was like, “What am I going to do about that?” because he lived in California and I lived in New York. I wasn’t really making ends meet in New York, and I wanted to be more serious about comics, whatever that meant, and I was still so young that I could just see what unfolded. And when I visited Trevor he was living in Santa Rosa, which is—compared to New York—a smaller town, and you could work half-time. And it seemed like you could afford to be an artist there in a way that you couldn’t in New York. And so it was sort of this practical and romantic thing where I was embracing both Trevor and comics: like everything would become more serious by moving out there.

Did your work developed in different ways, because the pressures of making a living in New York and space and so on were now slightly eased?

Yeah, they were definitely eased, but then also moving and having a serious boyfriend and making friends in a new town took up some of the attention that I was giving to working. But then in comics, basically what I was OK with happening was Spaniel Rage got a little attention. And so I got to be in some anthologies; like, in Kramers Ergot they needed something in color, so I was like, “OK, that’s a challenge to attack, how will I do comics in color, in ink?” And then in another anthology I had to do a six-page story, and I had never done that before. So I felt like I was in a position where I was getting to do new projects that would stretch my abilities. So I spent a lot of time in that place. I knew that even though I had this book published, I was new to this form, and kind of didn’t really know what I was doing and was open to seeing where it went. But then, shortly after I moved to California, Alvin and I kind of fell out, and Alvin, to a large extent, was my conduit to fancier, more ambitious projects. And so even though I had a good reputation independently, I has living out in the boonies, publishing-wise, and I had lost my hip publisher contact, so I sort of languished in a really pleasant kind of slow, goalless development for a long time.

There’s something in your comics that has this combination of ambition on the one hand but also this coziness.

Yeah, I want to go at my own pace, I want to do things that I want to do, and I don’t want to succeed at the expense of feeling connected to my work.

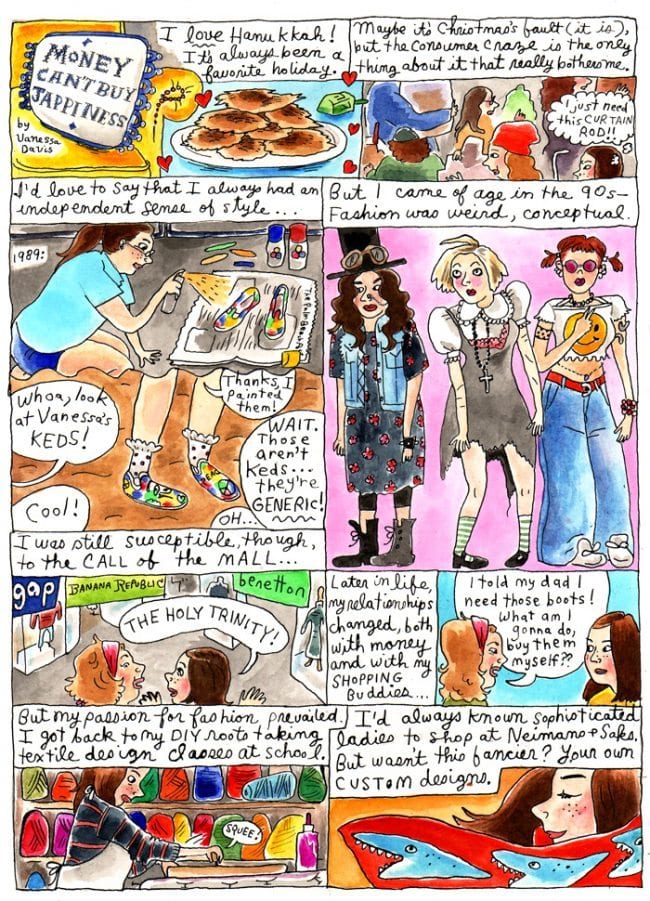

When you were living Santa Rosa, you also had a column for Tablet, where did longer-form color comics.

I got really lucky with the Tablet assignment, because it was a column—they weren’t really that long, they were only like 3 pages, but getting to do a new comic every month for money—and they paid really well—was amazing. So I really wanted to meet the challenge, enjoy this gift that had been bestowed upon me. Because it was such an unusual kind of job to get to have. I got to write about myself, and I got to write about things in my own personality, but it was a weird mix, because on the one hand they were like, “Okay, let’s do something about Hanukkah,” and I don’t know that that necessarily was on the top of my mind, to make a comic about Hanukkah—

Why not. What do you mean? [Laughter.]

But then it turned out that there was a well of stuff that I had where I could talk about Hanukkah. So it was sort of interesting, because I definitely made a lot of commercial compromises and artistic compromises to fit the assignment, but it was worth it to me because it was such a great opportunity and I was being treated so respectfully as a columnist, compared to most of the other offerings out there. My father [the late Gerald Davis] was a commercial artist. He was a photojournalist, but he also was this amazing artist and he really balanced those two things in a really pragmatic way. And I think that really spoke to me as a burgeoning illustrator/cartoonist for hire. I was like, “I can still make this my own and also make it legible to my mom’s friends who are going to read it on Tablet.” I just didn’t see those as mutually exclusive. So it was a time when, all of a sudden—when it definitely hadn’t been before—it became maybe possible to have this be a job. And so I wanted to explore that as much as possible. I got to do it for about a year and a half.

But then it turned out that there was a well of stuff that I had where I could talk about Hanukkah. So it was sort of interesting, because I definitely made a lot of commercial compromises and artistic compromises to fit the assignment, but it was worth it to me because it was such a great opportunity and I was being treated so respectfully as a columnist, compared to most of the other offerings out there. My father [the late Gerald Davis] was a commercial artist. He was a photojournalist, but he also was this amazing artist and he really balanced those two things in a really pragmatic way. And I think that really spoke to me as a burgeoning illustrator/cartoonist for hire. I was like, “I can still make this my own and also make it legible to my mom’s friends who are going to read it on Tablet.” I just didn’t see those as mutually exclusive. So it was a time when, all of a sudden—when it definitely hadn’t been before—it became maybe possible to have this be a job. And so I wanted to explore that as much as possible. I got to do it for about a year and a half.

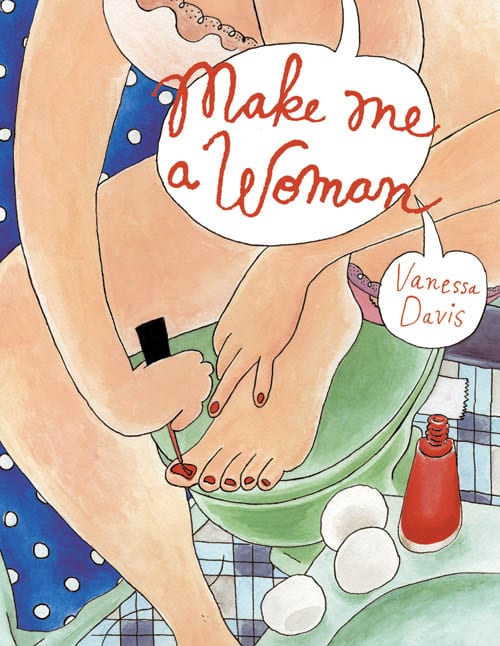

Your second book, Make Me a Woman, which came out with Drawn and Quarterly in 2010, was mostly a collection of the Tablet things with some things in between, right?

Make Me a Woman captured that period in Santa Rosa where I was open to whatever came across my path. I didn’t know if I just wanted to put Spaniel Rage #2, but I also didn’t feel that I was ready to do a graphic novel. But then it was an interesting experience because working with Tom [Devlin, of Drawn and Quarterly] on the book—we both wanted to see if something emerged from the collection, something unintended. Certainly there were themes that ran throughout the book, but it was also kind of like “who’s making this a book, is it me? Did I intend for this to be my book, or am I going to let accidental threads determine that it’s a book”? In a way, I thought that was the most interesting thing about Make Me a Woman.

“I’m Not Going to Cannibalize Myself”

How do you think gender played into people’s perceptions of what you were doing?

I’ve read criticisms of all my comics from Spaniel Rage onwards: people who said that were told that “this is really raw and really honest, but it’s not even really deep”; like, “she just talks about her hair or she talks about shopping” or something. I think that femininity and masculinity definitely play into those things, but from my perspective, being in it, it’s kind of hard to see where it starts and stops, because I know it’s also a personality thing. Some people get inspired when they see vulnerability, and some people get inspired when they see mastery. And I think that’s an ingrained value system alongside these different cultural expectations we have of men and women.

And what was your reaction to people who complained that even within the realm of diary comics, your work was not giving the reader “the juice of womanhood”? [Laughter.]

Well, I have various reactions to that. On the one hand, those people had preconceived ideas about what they want, and so if I fell short of that I can’t really help it. And sometimes, in my crankier moments, I just feel like: how entitled are people, or how does that speak to what people want from a book? I’m an autobiographical cartoonist, I have to take a lot of effort when I portray other people not to exploit them, but just as much I don’t plan on exploiting myself. I am happy to be open and to be confessional and talk about personal things, but I’m not going to cannibalize myself so that some random person is going to be satisfied. That’s not my job.

So when you write about yourself, what are you aiming to get at?

Fundamentally, I write about myself to connect with other people. I just think there’s a range. There’s a range of what’s personal. And there are other ways to be revealing than to be literally revealing. I think that Spaniel Rage is clearly revealing in the sense that it’s someone’s first effort in a new medium, and so it’s not necessarily interpersonally raw but it’s artistically raw, and that can be revealing in its own way.

Is there something particular that you hope people might get out of your work?

Well, I always hope people will enjoy the view into another person's mind, which is what I like about comics. Maybe they relate, or maybe it's just another perspective. I do think that view changes. I was thinking about Spaniel Rage, looking at it again, and I realized that a lot of what I was drawing about was maybe to see if other people were thinking the same things as I was, or going through the same things. Sort of like, “Hey, am I doing this right? Is this familiar, or what?” It was a way to reveal what I was doing and see if it meshed with other people. But then I think that changed for me, because now I know that everyone leads these idiosyncratic lives—sometimes you connect with people, sometimes you don’t—but there are so many other motivations for me: like sometimes I want to remember things, or sometimes I have a beef that I want to work out. Like when I moved to L.A., I started observing these things about humanity, and you’re like, “Am I crazy? Is this really how people act?” I think my comics have always been a way for me to examine my observations and connect with other people.

“A Colorful-Sounding Job Opportunity”

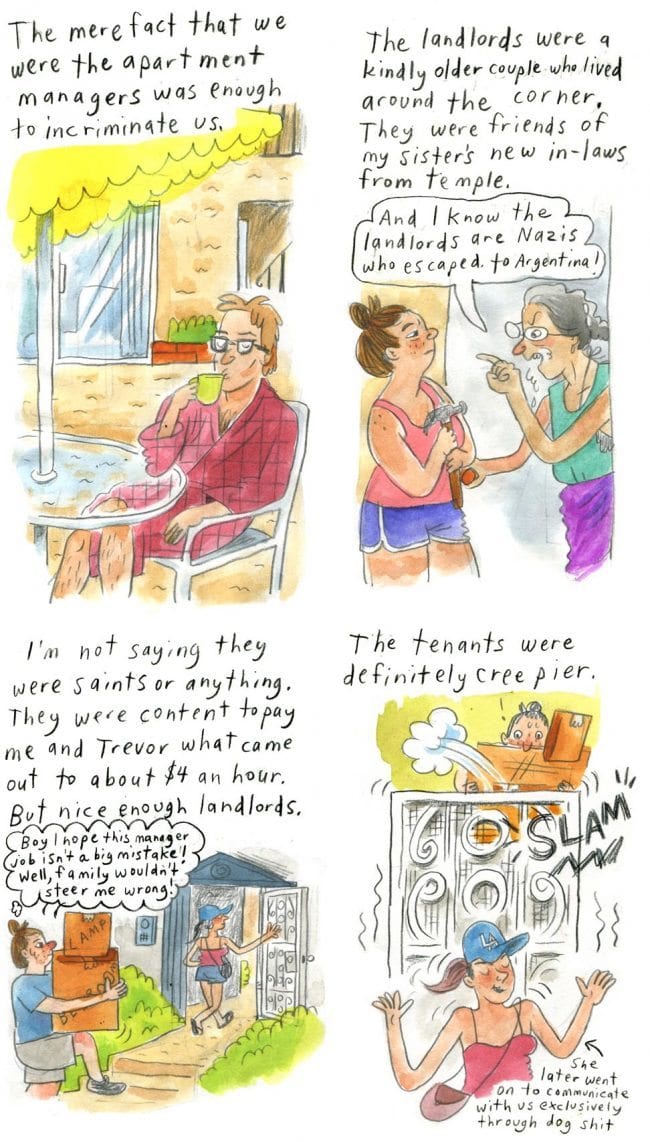

After living in Santa Rosa for several years, you decided to move to Los Angeles with Trevor to become apartment managers.

[Laughs] Yes, I did. It taught me a lot of things, like any horrible experience does. Living in Santa Rosa was amazing at first. It was like this permanent vacation and I had a part-time job as a secretary, and I just had so much time and freedom. But then after a while, it had been like years and I hadn’t made any decisions about what I was—and nothing seemed to be changing, and Trevor started to feel that way. We were like, “We’d like to make a decision about where we’re going to end up. So maybe we should try something different so that at least we had done that process where we’ve made a choice about where we’re going to be.” It was really hard to leave because it was so comfortable there, and Trevor’s job was really great. Then this colorful-sounding job opened up and we could split the work and get a free apartment. It was supposed to be like 20 hours a week, and we’d move to Hollywood and what an adventure that would be. You know, Santa Rosa’s a small town, we were staying in state, it didn’t seem like a big risk. So we figured we’d try it out, and it actually it was really challenging because—

So it was an apartment complex that was full of has-beens and never-weres?

Yes, not to be harsh. There were a handful of very nice people, but the overwhelming—it wasn’t like a corporate-run apartment building, it was sort of—I used to say to prospective tenants that it was sort of like an independent bookstore. Where they might not have the newest things, but they’ll cater to your—I don’t know how it was like an independent bookstore but it was like—[Laughter]—like on the one hand people were like, “The plumber might come and trash your apartment” but on the other hand—

“It’ll be like family” [Laughs]

But on the other hand if you wanted someone to help put up your curtain rods, like the entire painting team would come and do it on a Saturday. The landlords—the couple who owned the building—were this very nice couple who loved—this was like their retirement, owning this building, and they loved interacting with the tenants, and they loved being social. It was kind of their pet project. But ultimately they got to make all of the decisions, and Trevor and I were brought in to sort of enforce rules that no one was expected to follow. No one bothered following, or cared about following, and there were like no repercussions if they didn’t follow them. And I like being friendly to neighbors but I’m not a busybody, I don’t care, I’m not interested in it. So being all of a sudden put into this role—which we chose to do—but choosing to be in this role of “you did this wrong, or you need to blah blah blah,” sucked. It was really foreign and weird, and they didn’t like it either. It was clear that we sucked at it, so it was just like this really stupid choice that we made, to do this job.

So the people—except for a handful of very nice people—there were some challenging characters. But on the relative plus side, it gave you a lot of material to think about, didn’t it?

Yeah, it’s interesting because it comes back to that exploitation idea that I brought up. Where it sounds—certainly I thought that it would be great for material. I intended to try and turn it into material. One thing that was sort of interesting was that when we would go places people wanted us to dine out on our colorful tenants, and talk about what a horrible experience it was. While we would tell them about it I would see their expressions go from laughing and smiling to kind of checking out, to being a little bit disgusted.

Well, for the record, I was always into it. [Laughter]

It was an interesting lesson in attitude and perspective. Because some stories are inherently interesting, but then they can be ruined by not being able to see them in their full breadth of interestingness. When you’re oppressed by experiences it’s hard to see them clearly—that was an interesting lesson, though I haven’t figured out a way to tell that story yet.

“Little Things Make a Life”

Did the negative apartment managing experience change your perspective about what kind of comics you want to make?

I know that when I started making comics, when I was drawing Spaniel Rage, I was becoming more well-read in comics, and I was seeing these themes of these ‘90s cartoonists with these hardened cynical viewpoints. Like telling dark stories, and really dark views of the world, and I got that. But I was also like, “I’m like this young girl who’s been pretty lucky.” I’ve had some bad things happen in my life, but overall, I would say that at the time I had this very sunny disposition and I was like, “where is the place in comics for that?” I think that also can sometimes work at odds with expectation of diary comics, because people want to read about the struggles, and the darkest experiences. I remember that it was deliberate that I wanted to bring this sort of like—not exactly basic suburban Jewish girl perspective—but I was like, “I don’t have to fit some mold of what a cartoonist looks like. I can be myself, I can talk about shopping. I also don’t necessarily want to be stuck making comics about the things that have the most plot necessarily. Maybe that was like this really amazingly colorful experience in my life, but I have this instinct to ignore the meaty stories, and try to find the meat in the fluff if that makes sense.

You also want to see if it resonates. And to say something about culture and about life.

Yeah. Or like, I remember when I started noticing that all the cars were shaped the same. And I would idly mention this to Trevor or to a friend; I’d be like, “Hey, have you noticed that everything looks like a Prius?” And it was not a very interesting observation, but it was nagging at me, and so I made a comic about it. So it forced people to contend with this small idea that I had. And so it satisfied that in me.

One of the only longer comics in Spaniel Rage is about how your parents’ cat would always bat around the paper your father’s dentures were wrapped in, and how after your father died, you discovered all of these old denture papers under the refrigerator. It’s very poignant.

I feel sort of amazed that I did that comic at such an early stage in my comics-making effort, because I actually think that that comic is the kernel that contains my whole M.O. It’s like my dad said, “little things make a life,” and I recognized it when he said it and I have since adhered to it. I’ve held it up as a guiding principle. I think that big things happen, you have no control over it at all, but I do think that there is all of this power in these small things, and they’re the things that I use to connect with being alive. I feel this loyalty to them, to focus on them, rather than these big things, because they’re more personal and they’re more real in a way than the big things that have happened to me.

“Resist in Existence”

I’m interesting in the turn that your work has taken now that—not that many people have seen it—but you’ve been drawing larger-scale figures now.

For the past couple of years I’ve had this really long, really fun, really lucrative illustration assignment for a couple of years where I was happily a cog in a machine. I loved it and it paid really well, but that took up a lot of time, so I didn’t do any comics during that whole period. Then that ended and I had a bunch of money in savings, and I hadn’t done comics in a really long time, and I kind of had no idea where to start. So I was like, “Oh I should rent a studio.” Usually when I don’t know what I’m doing with comics I’ll do diary comics, but as I’ve gotten older and life has gotten more difficult, I have sort of like a fraught relationship with—and I almost sounded angry before when I was talking about people wanting things from me. I had a moment when I was feeling extra protective about my personal life, and so I thought that I’ve never had a studio before, and so hadn’t gotten to do anything big—I’d been sitting for like three years drawing these illustrations, and I was like “I want to move around.” Prince died and I wanted to dance to Prince and draw and just see what I would do. So I’ve been doing these big drawings. I don’t really know exactly what they’re about, but it feels really pure and good to be doing them.

And they’re mostly figures?

VD: Yeah. It took me a long time to figure out how to scale up. Like, what materials to use—usually I draw with a mechanical pencil—so like how do you cover ground in the same way that you cover ground small? So I went through a bunch of different materials to see what I liked, then I kind of settled on these. Then it was like “well what am I drawing?” When the election was happening, I felt this weird combination feeling of wanting to protect myself and hide myself from these horrible people, but then also kind of like resist in existence. So I just wanted to revel in the female body, and my sister was like “what’s up with these nudes?” and it’s not like I’m a nudist or anything, but putting clothes on them made them more visually complicated, and it became a visual exercise to figure out how to portray the nudity. So I’ve just been really into that at the moment.

Around the same time you started making these large drawings in the studio, you were asked to do a comics column by the Paris Review, as well.

It had been a long time since I’ve made comics with any regularity, and it was a combination of really hard, and then like not having the time to worry about it, because it was a really tight deadline. But I think a combination of luck, experience, and “fuckitness” kind of came together to work. But it was a difficult experience because I did not feel like I had any control over whether the comics came out good or not.

Like in a way that you hadn’t felt before?

I think that I was being a little more ambitious conceptually with what I was discussing, and I was trying to make connections between things that I felt made sense but I wasn’t able to articulate necessarily, in any kind of convincing way. So I really felt like I floundered—it was very harrowing while I was making them, but then it was extremely satisfying when I was done with them, which is a classic experience [Laughter].

Would you ever like to expand your breadth even further and do a really long-form comic?

It’s not that I’m against it in itself. But it’s like I said before, I’m really drawn to these small stories and small instances. That thinking about something that would take that long to explore—I haven’t felt drawn to something that big. It’s not that I don’t know that I ever will, but… I’m friends with Mimi Pond, and she’s been working on this story that’s so long that it’s over two books, two novels, and it’s like a story that she loves and has loved for such a long time and she has a script. Besides a lot of things that are admirable about Mimi, like one thing that just sounds so amazing is sitting down with a story that you know, and having the script, and chipping away at it—that just sounds amazing to me. So I’d love to be in that situation, or to put myself in that situation, but I just don’t know if I’m going to go that way.

You don’t have to. [laughter]

That’s the thing! I don’t. Obviously there are a lot of people in comics who write books, and that’s great, but like, if you don’t, you can kind of be either way. I don’t have to be a best seller to be allowed to be here, which I like.